The Egyptian Fortress on Uronarti in the Late Middle Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three “Italian” Graffiti from Semna and Begrawiya North

Eugenio Fantusati THREE “ITALIAN” GRAFFITI FROM SEMNA AND BEGRAWIYA NORTH Egyptian monuments are known to bear texts and composed of soldiers, explorers, merchants and, signatures engraved by Western travelers who in the second wave clerics, was quite consider- thus left traces of their passage on walls, columns able. For a long time the call of the exotic and of and statues beginning after the Napoleonic ex- adventure drew many Italians to Africa. In the pedition. early 19th century, they had no qualms about Sudan, although less frequented, did not leaving a fragmented country, not only governed escape this certainly depreciable practice. Indeed, by foreign powers, but also the theatre of bloody none of the European explorers in Batn el-Hagar wars for independence. Their presence in Africa avoided the temptation to leave graffiti on grew progressively to such an extent that Italian, archaeological sites, as if there was some myster- taught in Khartoum’s missionary schools, became ious force pushing them to this act, undeniable the commercial language of the Sudan. For a long because visible, once they had reached their so time, it was employed both in the official docu- longed-for destination. ments of the local Austrian consulate and in the Even George Alexander Hoskins, antiquarian, Egyptian postal service before being definitely writer and excellent draftsman, who openly supplanted by French after the opening of the condemned the diffusion of the practice to deface Suez Canal (Romanato 1998: 289). monuments, admitted his own “guilt” in this Naturally, the many Italians visiting archae- respect: “I confess on my first visit to the Nile, ological sites in Nubia did not refrain from I wrote my name on one of the colossal statues in leaving graffiti just like the other Europeans. -

Kvinner I Det Gamle Egypt

Kvinner i det gamle Egypt Ein komparativ studie Avbiletinga viser ei kvinne som sit ute i det fri og sel fruktene frå ein sykamorebusk med eit barn tett til brystet. Ein ser såleis den komplekse naturen til kvinnerolla; På den eine sida som mor og omsorgsperson, og på den andre som kvinne med eige ressursgrunnlag og høve for eiga inntekt. Masteravhandling i antikk historie. Institutt for arkeologi, historie, kunst og religionsvitenskap. Universitetet i Bergen, våren 2009 Reinert Skumsnes Kvinner i det gamle Egypt FØREORD Eit masterstudium, ei avhandling og ei lang reise i tid og stad er til endes. Reisa har vore interessant, mykje takka rettleiaren min, professor Jørgen Christian Meyer. Hans lange fartstid og gode kunnskapar som historikar har hjelpt meg ut av mang ei fortvilt stund kor kvinnene i det gamle Egypt rett og slett ikkje ville same veg som meg. Både Christian og fyrsteamanuensis Ingvar Mæhle skal ha takk for låge dørstokkar, velvilje og solid, jordnær profesjonalitet. Frå det norske egyptologimiljøet takkar eg professor emeritus Richard H. Pierce (UiB), professor Saphinaz-Amal Naguib (UiO), Pål Steiner (UiB), Anders Bettum (UiO) og Vidar Edland for større og mindre bidrag, som alle har vore viktige. Likeeins vil eg gje ei stor takk til alle medstudentane mine som til ei kvar tid har vore tilgjengelege og positive i kaffikroken vår på Sydneshaugen. Arbeidet har vore omfattande, men likevel overkommeleg. Dei fleste kjeldene har allereie vore jobba mykje med, og har såleis skapt større rom for drøfting og utvida fagleg innsikt. Ei spesiell takk må eg her sende til professor Anthony Spalinger, professor Doborah Sweeeney, professor Andrea McDowell, og professor Schafik Allam som alle har vore villige til å svare på spørsmål eg har hatt knytt til deira arbeid med kjeldene. -

No. 6 a NEWSLETTER of AFRICAN ARCHAEOLOGY May 19 75 Edited

- No. 6 A NEWSLETTER OF AFRICAN ARCHAEOLOGY May 1975 Edited by P.L. Shinnie and issued from the Department of Archaeology, The University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta T2N lN4, Canada. (This issue edited by John H. Robertson.) I must apologize for the confusion which has developed con- cerning this issue. A notice was sent in February calling for material to be sent by March 15th. Unfortunately a mail strike in Canada held up the notices, and some people did not receive them until after the middle of March. To make matters worse I did not get back from the Sudan until May 1st so the deadline really should have been for the end of April. My thanks go to the contributors of this issue who I am sure wrote their articles under pressure of trying to meet the March 15th deadline. Another fumble on our part occurred with the responses we received confirming an interest in future issues of Nyame Akuma Professor ~hinnie'sintent in sending out the notice was to cull the now over 200 mailing list down to those who took the time to respond to the notice. Unfortunately the secretaries taking care of the-mail in Shinnie's absence thought the notice was only to check addresses, and only changes in address were noted. In other words, we have no record of who returned the forms. I suspect when Professor Shinnie returns in August he will want to have another go at culling the mailing list . I hope this issue of Nyame Akuma, late though it is, reaches everyone before they go into the field, and that everyone has an enjoyable and productive summer. -

The Semna South Project Louis V

oi.uchicago.edu The Semna South Project Louis V. Zabkar For those who have never visited the area of southern Egypt and northern Sudan submerged by the waters of the new Assuan High Dam, and who perhaps find it difficult to visualize what the "lake" created by the new Dam looks like, we include in this report two photographs which show the drastic geographic change which oc curred in a particular sector of the Nile Valley in the region of the Second Cataract. Before the flooding one could see the Twelfth Dynasty fortress; and, next to it, at the right, an extensive predominantly Meroitic and X-Group cemetery; the characteristic landmark of Semna South, the "Kenissa," or "Church," with its domed roof, built later on within the walls of the pharaonic fortress; the massive mud-brick walls of the fortress; and four large dumps left by the excavators—all this can be seen in the photo taken at the end of our excavations in April, 1968. On our visit there in April, 1971, the fortress was completely sub merged, the mud-brick "Kenissa" with its dome having collapsed soon after the waters began pounding against its walls. One can see black spots in the midst of the waters off the center which are the stones on the top of the submerged outer wall of the fortress. The vast cemetery is completely under water. In the distance, to the north, one can clearly see the fortress of Semna West, the glacis of which is also sub- 41 oi.uchicago.edu The area of Semna South included in our concession The Semna South concession submerged by the waters of the "lake 42 oi.uchicago.edu merged, and the brick walls of which may soon collapse through the action of the risen waters. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

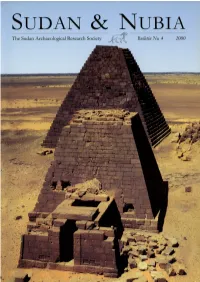

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Buhen in the New Kingdom

Buhen in the New Kingdom George Wood Background - Buhen and Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom Traditionally ancient Egypt ended at the First Cataract of the Nile at Elephantine (modern Aswan). Beyond this lay Lower Nubia (Wawat), and beyond the Dal Cataract, Upper Nubia (Kush). Buhen sits just below the Second Cataract, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Wadi Halfa, at what would have been a good location for ships to carry goods to the First Cataract. The resources that flowed from Nubia included gold, ivory, and ebony (Randall-MacIver and Woolley 1911a: vii, Trigger 1976: 46, Baines and Málek 1996: 20, Smith, ST 2004: 4). Egyptian operations in Nubia date back to the Early Dynastic Period. Contact during the 1st Dynasty is linked to the end of the indigenous A-Group. The earliest Egyptian presence at Buhen may have been as early as the 2nd Dynasty, with a settlement by the 3rd Dynasty. This seems to have been replaced with a new town in the 4th Dynasty, apparently fortified with stone walls and a dry moat, somewhat to the north of the later Middle Kingdom fort. The settlement seems to have served as a base for trade and mining, and royal seals from the 4th and 5th Dynasties indicate regular communications with Egypt (Trigger 1976: 46-47, Baines and Málek 1996: 33, Bard 2000: 77, Arnold 2003: 40, Kemp 2004: 168, Bard 2015: 175). The latest Old Kingdom royal seal found was that of Nyuserra, with no archaeological evidence of an Egyptian settlement after the reign of Djedkara. -

Hyksos, Egipcios, Nubios: Algunas Consideraciones Sobre El I1 Pe~Odointermedio Y La Convivencia Entre Los Distintos Grupos Etnicos

HYKSOS, EGIPCIOS, NUBIOS: ALGUNAS CONSIDERACIONES SOBRE EL I1 PE~ODOINTERMEDIO Y LA CONVIVENCIA ENTRE LOS DISTINTOS GRUPOS ETNICOS Inmaculada Vivas SBinz Universidad de AlcalB de Henares ABSTRACT This article reviews some questions of the political and social history of the the Second Intermediate Period. The first part is based on recent discussion about the terminology related to the period, and the convenience or unconvenience of using certain terms in future investigations. The second part concerns the relationships among the dlflerent ethnic groups living in Egypt at that time, and the process of acculturation of the Hyksos in Egypt. An interesting hypotheses about king Nehesy is analysed, which proposes the existence of a dynastic marriage between a Nubian queen and a king of the XIVth Dynasty, both being the suppoused parents of Nehesy. I reject this hypotheses on the basis of archaedogical and epigraphical sources. The true origin of Nehesy remains a moot point, being still d~ficultto explain why this king had a name meaning "the Nubian". -Los estudios sobre el I1 Periodo Intermedio egipcio se remontan a1 siglo pasado', pero es desde hace apenas unas dCcadas cuando se ha sentido la necesidad de definir ese tCrmino. Los primeros trabajos sobre el tema eran breves anilisis sobre el final del Reino Medio y la llegada de 10s hyksos, sobre Cstos y su relaci6n con Israel, o la posible ubicaci6n de Avaris y el proceso de expulsi6n de 10s hyksos. Todos estos estudios son importantes para nuestras investigaciones pero muchas veces se basan s610 en fuentes arqueol6gicas procedentes de Siria-Palestina de las cuales se extrapolaban datos para la situaci6n de Egipto. -

Egypt and Africa Presentation.Pdf

Egypt and Africa Map of the Second Cataract showing fortress area Different plan types of Nubian fortresses: Cataract fortresses Plains fortresses Fortress at Buhen: Plains Fortress Defensive Characteristics Askut: Cataract Fort Middle Kingdom institutions as shown by seal impressions First Semna Stela of Senwosret III Southern boundary, made in the year 8, under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khakaure Senwosret III who is given life forever and ever; in order to prevent that any Nubian should cross it, by water or by land, with a ship or with any herds of the Nubians, except a Nubian who shall come to do trading in Iqen (Mirgissa) or with a commission. Every good thing shall be done with them, but without allowing a ship of the Nubians to pass by Heh, going downstream, forever. Boundary Stela of Senwosret III from Semna (a duplicate found at Uronarti) “…I have made my boundary further south than my fathers, I have added to what was bequeathed me. I am a king who speaks and acts, What my heart plans is done by my arm… Attack is valor, retreat is cowardice, A coward is he who is driven from his border. Since the Nubian listens to the word of mouth, To answer him is to make him retreat. Attack him, he will turn his back, Retreat, he will start attacking. They are not people one respects, They are wretches, craven-hearted… As for any son of mine who shall maintain this border which my majesty has made, he is my son, born to my majesty. -

Mud-Brick Architecture

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Mud-Brick Architecture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4983w678 Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Emery, Virginia L. Publication Date 2011-02-19 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MUD-BRICK ARCHITECTURE عمارة الطوب اللبن Virginia L. Emery EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief Area Editor Material Culture University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Emery, 2011, Mud-Brick Architecture. UEE. Full Citation: Emery, Virginia L., 2011, Mud-Brick Architecture. In Willeke Wendrich (ed.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0026w9hb 1146 Version 1, February 2011 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0026w9hb MUD-BRICK ARCHITECTURE عمارة الطوب اللبن Virginia L. Emery Ziegelarchitektur L’architecture en brique crue Mud-brick architecture, though it has received less academic attention than stone architecture, was in fact the more common of the two in ancient Egypt; unfired brick, made from mud, river, or desert clay, was used as the primary building material for houses throughout Egyptian history and was employed alongside stone in tombs and temples of all eras and regions. Construction of walls and vaults in mud-brick was economical and relatively technically uncomplicated, and mud-brick architecture provided a more comfortable and more adaptable living and working environment when compared to stone buildings. على الرغم أن العمارة بالطوب اللبن تلقت إھتماما أقل من العمارة الحجرية من قِبَل المتخصصين، فقد كانت في الواقع تلك العمارة ھي اﻷكثر شيوعا في مصر القديمة، وكان الطوب اللبن (أوالنيء) المصنوع من الطمي أو الطين الصحراوي مستخدما كمادة بناء بدائية للمنازل على مدار التاريخ المصري واستخدمت إلى جانب الحجارة في المقابر والمعابد في جميع المناطق وخﻻل جميع الفترات. -

3 the Kingdom of Kush. Urban Defences and Military Installations

In : N. Crummy (ed.), Image, Craft and the Classical World. Essays in honour of Donald Bailey and Catherine Johns (Monogr. Instrumentum 29), Montagnac 2005, p. 39-54. 3 The Kingdom of Kush. Urban defences and military installations by Derek A. Welsby1 When the Romans took control of Egypt in 30 BC they with the rise of Aksum and the possible invasion of the came in direct contact on their southern frontier with the region around Meroe by the army of Aezanes (cf. Behrens Kingdom of Kush, the longest established state of any that 1986; Török 1997a, 483-4). they faced. Kush had been a major power at least since the Perhaps of more long-term concern were the low level mid 8th century BC at a time when Rome itself consisted raids mounted by the desert tribes on the fringes of the of little more than a group of huts on the Palatine. In the Nile Valley2. At least one of these incursions, during the th later 8 century BC the Kings of Kush ruled an empire reign of King Nastasen in the later 4th century BC, stretching from Central Sudan to the borders of Palestine resulted in the looting of a temple at Kawa in the Dongola controlling Egypt as pharaohs of what became known as Reach and earlier Meroe itself, the main political centre, th the 25 Dynasty. Forced to withdraw from Egypt in the seems to have been under threat. face of Assyrian aggression by the mid 7th century BC, they retreated south of the First Cataract of the Nile where they maintained control of the river valley far upstream of Urban defences the confluence of the White and Blue Niles at modern-day Khartoum, into the 4th century AD (Fig. -

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964)

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) Lake Nasser, Lower Nubia: photography by the author Degree project in Egyptology/Examensarbete i Egyptologi Carolin Johansson February 2014 Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University Examinator: Dr. Sami Uljas Supervisors: Prof. Irmgard Hein & Dr. Daniel Löwenborg Author: Carolin Johansson, 2014 Svensk titel: Digital rekonstruktion av det arkeologiska landskapet i koncessionsområdet tillhörande den Samnordiska Expeditionen till Sudanska Nubien (1960–1964) English title: Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) A Magister thesis in Egyptology, Uppsala University Keywords: Nubia, Geographical Information System (GIS), Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE), digitalisation, digital elevation model. Carolin Johansson, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Box 626 SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. Abstract The Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE) was one of the substantial contributions of crucial salvage archaeology within the International Nubian Campaign which was pursued in conjunction with the building of the High Dam at Aswan in the early 1960’s. A large quantity of archaeological data was collected by the SJE in a continuous area of northernmost Sudan and published during the subsequent decades. The present study aimed at transferring the geographical aspects of that data into a digital format thus enabling spatial enquires on the archaeological information to be performed in a computerised manner within a geographical information system (GIS). The landscape of the concession area, which is now completely submerged by the water masses of Lake Nasser, was digitally reconstructed in order to approximate the physical environment which the human societies of ancient Nubia inhabited. -

In Lower Nubia During the UNESCO Salvage Campaign in the 1960S, Only One, Fadrus, Received Any Robust Analytical Treatment

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CONTINUITY AND CHANGE: A REEVALUATION OF CULTURAL IDENTITY AND “EGYPTIANIZATION” IN LOWER NUBIA DURING THE NEW KINGDOM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY LINDSEY RAE-MARIE WEGLARZ CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2017 Copyright © 2017 Lindsey Rae-Marie Weglarz All rights reserved Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... vi List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... ix Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... x Chapter 1 : Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Historical Background ................................................................................................................................ 3 Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom ................................................................................................. 3 The Conquest