In Lower Nubia During the UNESCO Salvage Campaign in the 1960S, Only One, Fadrus, Received Any Robust Analytical Treatment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

No. 6 a NEWSLETTER of AFRICAN ARCHAEOLOGY May 19 75 Edited

- No. 6 A NEWSLETTER OF AFRICAN ARCHAEOLOGY May 1975 Edited by P.L. Shinnie and issued from the Department of Archaeology, The University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta T2N lN4, Canada. (This issue edited by John H. Robertson.) I must apologize for the confusion which has developed con- cerning this issue. A notice was sent in February calling for material to be sent by March 15th. Unfortunately a mail strike in Canada held up the notices, and some people did not receive them until after the middle of March. To make matters worse I did not get back from the Sudan until May 1st so the deadline really should have been for the end of April. My thanks go to the contributors of this issue who I am sure wrote their articles under pressure of trying to meet the March 15th deadline. Another fumble on our part occurred with the responses we received confirming an interest in future issues of Nyame Akuma Professor ~hinnie'sintent in sending out the notice was to cull the now over 200 mailing list down to those who took the time to respond to the notice. Unfortunately the secretaries taking care of the-mail in Shinnie's absence thought the notice was only to check addresses, and only changes in address were noted. In other words, we have no record of who returned the forms. I suspect when Professor Shinnie returns in August he will want to have another go at culling the mailing list . I hope this issue of Nyame Akuma, late though it is, reaches everyone before they go into the field, and that everyone has an enjoyable and productive summer. -

Life in Egypt During the Coptic Period

Paper Abstracts of the First International Coptic Studies Conference Life in Egypt during the Coptic Period From Coptic to Arabic in the Christian Literature of Egypt Adel Y. Sidarus Evora, Portugal After having made the point on multilingualism in Egypt under Graeco- Roman domination (2008/2009), I intend to investigate the situation in the early centuries of Arab Islamic rule (7th–10th centuries). I will look for the shift from Coptic to Arabic in the Christian literature: the last period of literary expression in Coptic, with the decline of Sahidic and the rise of Bohairic, and the beginning of the new Arabic stage. I will try in particular to discover the reasons for the tardiness in the emergence of Copto-Arabic literature in comparison with Graeco-Arabic or Syro-Arabic, not without examining the literary output of the Melkite community of Egypt and of the other minority groups represented by the Jews, but also of Islamic literature in general. Was There a Coptic Community in Greece? Reading in the Text of Evliya Çelebi Ahmed M. M. Amin Fayoum University Evliya Çelebi (1611–1682) is a well-known Turkish traveler who was visiting Greece during 1667–71 and described the Greek cities in his interesting work "Seyahatname". Çelebi mentioned that there was an Egyptian community called "Pharaohs" in the city of Komotini; located in northern Greece, and they spoke their own language; the "Coptic dialect". Çelebi wrote around five pages about this subject and mentioned many incredible stories relating the Prophets Moses, Youssef and Mohamed with Egypt, and other stories about Coptic traditions, ethics and language as well. -

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators this is max size of image at 200 dpi; the sil is low res and for the comp only. if approved, needs to be redone carefully American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts © 2006 American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs: Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum is organized by the American Federation of Arts and The British Museum. All materials included in this resource may be reproduced for educational American Federation of Arts purposes. 212.988.7700 800.232.0270 The AFA is a nonprofit institution that organizes art exhibitions for presen- www.afaweb.org tation in museums around the world, publishes exhibition catalogues, and interim address: develops education programs. 122 East 42nd Street, Suite 1514 New York, NY 10168 after April 1, 2007: 305 East 47th Street New York, NY 10017 Please direct questions about this resource to: Suzanne Elder Burke Director of Education American Federation of Arts 212.988.7700 x26 [email protected] Exhibition Itinerary to Date Oklahoma City Museum of Art Oklahoma City, Oklahoma September 7–November 26, 2006 The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens Jacksonville, Florida December 22, 2006–March 18, 2007 North Carolina Museum of Art Raleigh, North Carolina April 15–July 8, 2007 Albuquerque Museum of Art and History Albuquerque, New Mexico November 16, 2007–February 10, 2008 Fresno Metropolitan Museum of Art, History and Science Fresno, California March 7–June 1, 2008 Design/Production: Susan E. -

The Egyptian Predynastic and State Formation

J Archaeol Res DOI 10.1007/s10814-016-9094-7 The Egyptian Predynastic and State Formation Alice Stevenson1 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract When the archaeology of Predynastic Egypt was last appraised in this journal, Savage (2001a, p. 101) expressed optimism that ‘‘a consensus appears to be developing that stresses the gradual development of complex society in Egypt.’’ The picture today is less clear, with new data and alternative theoretical frameworks challenging received wisdom over the pace, direction, and nature of complex social change. Rather than an inexorable march to the beat of the neo-evolutionary drum, primary state formation in Egypt can be seen as a more syncopated phenomenon, characterized by periods of political experimentation and shifting social boundaries. Notably, field projects in Sudan and the Egyptian Delta together with new dating techniques have set older narratives of development into broader frames of refer- ence. In contrast to syntheses that have sought to measure abstract thresholds of complexity, this review of the period between c. 4500 BC and c. 3000 BC tran- scends analytical categories by adopting a practice-based examination of multiple dimensions of social inequality and by considering how the early state may have become a lived reality in Egypt around the end of the fourth millennium BC. Keywords State formation Á Social complexity Á Neo-evolutionary theory Á Practice theory Á Kingship Á Predynastic Egypt Introduction Forty years ago, the sociologist Abrams (1988, p. 63) famously spoke of the difficulty of studying that most ‘‘spurious of sociological objects’’—the modern state. -

Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: an Archaeological Note

Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies Volume 3 Know-Hows and Techniques in Ancient Sudan Article 3 2016 Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note Sebastien Maillot [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns Recommended Citation Maillot, Sebastien (2016) "Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note," Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies: Vol. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns/vol3/iss1/3 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 41 Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note Sébastien Maillot* The Kushite temples of Amun at Dukki Gel1 and Dangeil2 (fig. 1) fea- ture in their precincts large heaps of ash mixed with ceramic coni- cal moulds (or “bread moulds”), which are dumps associated with the production of food offerings for the cult. Excavation of the areas dedicated to these activities resumed in 2013 at both sites, uncover- ing numerous firing and storage features. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

Traveling Within Pharaonic Egypt for Discovering the Past

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 3, No. 1, (2017), pp. 15-21 Copyright © 2017 SC Open Access. Printed in Greece. All Rights Reserved. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.192840 TRAVELING WITHIN PHARAONIC EGYPT FOR DISCOVERING THE PAST Sherine El-Menshawy Qatar University, College of Arts and Sciences, Humanities Department, B.O. 2713, QU, Qatar Received: 24/10/2016 Accepted: 11/12/2016 ([email protected]) ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to assess to what degree were archaeological visits in ancient Egypt is regarded as visits of historical or touristical purpose. Research questions include: Who traveled, where and why? The accessibility of the visited places, the preferred season for such visits, the visitors‘ ethics in relation to the ancient monuments, the provisions carried with them and the preferable means of travel will be discussed. Evidence for those visits will be discussed, followed by analytical argument. KEYWORDS: Archaeological visits, category, motivations and ethics of visitors, carried provisions, means of travel. 16 S. EL-MENSHAWY 1. INTRODUCTION 2011; Navrátilová, 2013). Places and kings‘ names mentioned in the graffiti suggest that history and Archaeological visits have long existed in ancient geography were part of the New Kingdom scribes‘ Egypt, my aim is to assess to what extent were those education, where scribes were able to show their visits viewed as visits of historical or touristical knowledge about the former sovereigns by scrib- purpose? Much like contemporary times ancient bling their titles and names in the graffiti (Navrátilo- people travelled around for various purposes. The vá, 2011). A well-known scribe was Nebnetjeru who research attempts to answer further questions such left graffiti from Kalabsha and Dendur till Toshka as sites visited (where?), the identity of the ancient (Černý, 1947). -

Egyptian Ushabtis HIXENBAUGH ANCIENT ART 320 East 81St Street New York, NY 10028

Hixenbaugh Ancient Art 320 East 81st Street New York Servants for Eternity: Egyptian Ushabtis HIXENBAUGH ANCIENT ART 320 East 81st Street New York, NY 10028 Tuesday - Saturday 11 to 6 and by appointment For more information and to view hundreds of other fine authentic antiquities see our web site: www.hixenbaugh.net [email protected] 212.861.9743 Member: International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA) Appraisers Association of America (AAA) Art and Antique Dealers League of America (AADLA) Confederation Internationale des Negociants en Oeuvres d'Art (CINOA) All pieces are guaranteed authentic and as described and have been acquired and imported in full accordance with all U.S. and foreign regulations governing the antiquities trade. © Hixenbaugh Ancient Art Ltd, 2014 Table of Contents 1. Overview (page 3) 2. New Kingdom Limestone Ushabti (page 4) 3. Crown Prince Khaemwaset (pages 5 - 7) 4. Queen Isetnofret (page 8) 5. Crown Prince Ramesses (page 8) 6. Princess Meryetptah (page 9) 7. Hori (page 10) 8. Prince Maatptah (page 11) 9. Huy (page 11) 10. Neferrenpet (pages 12 - 13) 11. Overseer (Reis) Ushabtis (page 14) 12. New Kingdom Ladies of the House (page 15) 13. High Priestess, Divine Adoratrice, Henuttawy (pages 16 - 17) 14. Third Intermediate Period Ushabtis (pages 18 - 19) 15. Late Period Ushabtis (pages 20 - 21) 16. Select Reading (page 22) 1 Overview Ushabtis (shabtis or shawabtis), ancient Egyptian mummiform statuettes, have long fascinated Egyptologists and collectors of ancient art. The ushabti’s appeal manifests itself on multiple levels – artistic, historical, and epigraphic. Since these mummiform tomb figures were produced in great numbers in antiquity and vary widely in terms of quality, medium, and size, they are available to collectors today of different tastes and at all price levels. -

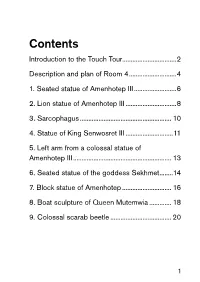

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour

Contents Introduction to the Touch Tour................................2 Description and plan of Room 4 ............................4 1. Seated statue of Amenhotep III .........................6 2. Lion statue of Amenhotep III ..............................8 3. Sarcophagus ...................................................... 10 4. Statue of King Senwosret III ............................11 5. Left arm from a colossal statue of Amenhotep III .......................................................... 13 6. Seated statue of the goddess Sekhmet ........14 7. Block statue of Amenhotep ............................. 16 8. Boat sculpture of Queen Mutemwia ............. 18 9. Colossal scarab beetle .................................... 20 1 Introduction to the Touch Tour This tour of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery is a specially designed Touch Tour for visitors with sight difficulties. This guide gives you information about nine highlight objects in Room 4 that you are able to explore by touch. The Touch Tour is also available to download as an audio guide from the Museum’s website: britishmuseum.org/egyptiantouchtour If you require assistance, please ask the staff on the Information Desk in the Great Court to accompany you to the start of the tour. The sculptures are arranged broadly chronologically, and if you follow the tour sequentially, you will work your way gradually from one end of the gallery to the other moving through time. Each sculpture on your tour has a Touch Tour symbol beside it and a number. 2 Some of the sculptures are very large so it may be possible only to feel part of them and/or you may have to move around the sculpture to feel more of it. If you have any questions or problems, do not hesitate to ask a member of staff. -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie Orientale

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 114 (2014), p. 455-518 Nico Staring The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara nico staring* Introduction In 2005 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired a photograph taken by French Egyptologist Théodule Devéria (fig. -

The Origins and Afterlives of Kush

THE ORIGINS AND AFTERLIVES OF KUSH ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS PRESENTED FOR THE CONFERENCE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA: JULY 25TH - 27TH, 2019 Introduction ....................................................................................................3 Mohamed Ali - Meroitic Political Economy from a Regional Perspective ........................4 Brenda J. Baker - Kush Above the Fourth Cataract: Insights from the Bioarcheology of Nubia expedition ......................................................................................................4 Stanley M. Burnstein - The Phenon Letter and the Function of Greek in Post-Meroitic Nubia ......................................................................................................................5 Michele R. Buzon - Countering the Racist Scholarship of Morphological Research in Nubia ......................................................................................................................6 Susan K. Doll - The Unusual Tomb of Irtieru at Nuri .....................................................6 Denise Doxey and Susanne Gänsicke - The Auloi from Meroe: Reconstructing the Instruments from Queen Amanishakheto’s Pyramid ......................................................7 Faïza Drici - Between Triumph and Defeat: The Legacy of THE Egyptian New Kingdom in Meroitic Martial Imagery ..........................................................................................7 Salim Faraji - William Leo Hansberry, Pioneer of Africana Nubiology: Toward a Transdisciplinary