The Egyptian Predynastic and State Formation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evaluation of Two Recent Theories Concerning the Narmer Palette1

Eras Edition 8, November 2006 – http://www.arts.monash.edu.au/eras An Evaluation of Two Recent Theories Concerning the Narmer Palette1 Benjamin P. Suelzle (Monash University) Abstract: The Narmer Palette is one of the most significant and controversial of the decorated artefacts that have been recovered from the Egyptian Protodynastic period. This article evaluates the arguments of Alan R. Schulman and Jan Assmann, when these arguments dwell on the possible historicity of the palette’s decorative features. These two arguments shall be placed in a theoretical continuum. This continuum ranges from an almost total acceptance of the historical reality of the scenes depicted upon the Narmer Palette to an almost total rejection of an historical event or events that took place at the end of the Naqada IIIC1 period (3100-3000 BCE) and which could have formed the basis for the creation of the same scenes. I have adopted this methodological approach in order to establish whether the arguments of Assmann and Schulman have any theoretical similarities that can be used to locate more accurately the palette in its appropriate historical and ideological context. Five other decorated stone artefacts from the Protodynastic period will also be examined in order to provide historical comparisons between iconography from slightly earlier periods of Egyptian history and the scenes of royal violence found upon the Narmer Palette. Introduction and Methodology Artefacts of iconographical importance rarely survive intact into the present day. The Narmer Palette offers an illuminating opportunity to understand some of the ideological themes present during the political unification of Egypt at the end of the fourth millennium BCE. -

Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part 45: Birds Statues (Falcon and Vulture)

International Journal of Emerging Engineering Research and Technology Volume 5, Issue 3, March 2017, PP 39-48 ISSN 2349-4395 (Print) & ISSN 2349-4409 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.22259/ijeert.0503004 Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part 45: Birds Statues (Falcon and Vulture) Galal Ali Hassaan (Emeritus Professor), Department of Mechanical Design & Production, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt ABSTRACT The evolution of mechanical engineering in ancient Egypt is investigated in this research paper through studying the production of statues and figurines of falcons and vultures. Examples from historical eras between Predynastic and Late Periods are presented, analysed and aspects of quality and innovation are outlined in each one. Material, dynasty, main dimension (if known) and present location are also outlined to complete the information about each statue or figurine. Keywords: Mechanical engineering, ancient Egypt, falcon statues, vulture statues INTRODUCTION This is the 45th paper in a scientific research aiming at presenting a deep insight into the history of mechanical engineering during the ancient Egyptian civilization. The paper handles the production of falcon and vulture statues and figurines during the Predynastic and Dynastic Periods of the ancient Egypt history. This work depicts the insight of ancient Egyptians to birds lived among them and how they authorized its existence through statuettes and figurines. Smith (1960) in his book about ancient Egypt as represented in the Museum of Fine Arts at Boston presented a number of bird figurines including ducks from the Middle Kingdom, gold ibis from the New Kingdom and a wooden spoon in the shape of a duck and lady from the New Kingdom [1]. -

Was the Function of the Earliest Writing in Egypt Utilitarian Or Ceremonial? Does the Surviving Evidence Reflect the Reality?”

“Was the function of the earliest writing in Egypt utilitarian or ceremonial? Does the surviving evidence reflect the reality?” Article written by Marsia Sfakianou Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom..........................2 How writing began.........................................................................................................4 Scopes of early Egyptian writing...................................................................................6 Ceremonial or utilitarian? ..............................................................................................7 The surviving evidence of early Egyptian writing.........................................................9 Bibliography/ references..............................................................................................23 Links ............................................................................................................................23 Album of web illustrations...........................................................................................24 1 Map of Egypt. Late Predynastic Period-Early Dynastic (Grimal, 1994) Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom (from the appendix of Grimal’s book, 1994, p 389) 4500-3150 BC Predynastic period. 4500-4000 BC Badarian period 4000-3500 BC Naqada I (Amratian) 3500-3300 BC Naqada II (Gerzean A) 3300-3150 BC Naqada III (Gerzean B) 3150-2700 BC Thinite period 3150-2925 BC Dynasty 1 3150-2925 BC Narmer, Menes 3125-3100 BC Aha 3100-3055 BC -

Cover Page the Handle

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/42753 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Moezel, K.V.J. van der Title: Of marks and meaning : a palaeographic, semiotic-cognitive, and comparative analysis of the identity marks from Deir el-Medina Issue Date: 2016-09-07 2 THE ORIGIN OF THE MARKS Identity marks have been used throughout Egyptian history. They are amply attested at several sites in Egypt, in the Early Dynastic Period as potmarks, and in the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms as potmarks, builders’ and quarry marks. The use of identity marks for individual workmen, however, and the extent to which they were used on ostraca for administrative purposes are peculiar to Deir el-Medina and the Theban necropolis. Also, the intensity of applying the marks in private context on personal objects such as neck supports, pots, bowls, stools, combs and linen found in the village, the workmen’s huts as well as in tombs, and their use in graffiti throughout the Theban mountains is unique for the community. How can we explain this? To what extent are the marks from Deir el-Medina a continuation of earlier practices? Why and when do we begin to observe the trend toward individuality and personal use? In this chapter we discuss the marks from the Theban necropolis in a broader Egyptian context in order to find out how the system came about, in form as well as in function and usage. We begin with a discussion of potmarks (section 1), followed by a discussion of builders’ marks (section 2), and finally a discussion of quarry marks (section 3). -

Displaced Human Skeletal Remains in Predynastic Period

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2016 Displaced human skeletal remains in predynastic period Sarah Marei Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Marei, S. (2016).Displaced human skeletal remains in predynastic period [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/261 MLA Citation Marei, Sarah. Displaced human skeletal remains in predynastic period. 2016. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/261 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Science Displaced Human Skeletal Remains in the Predynastic Period A Thesis Submitted to Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Psychology, and Egyptology In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The degree of Master of Arts By: Sarah Marei Under the supervision of Dr. Lisa Sabbahy & Dr. Salima Ikram May 2016 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my father, who gave me several lifetimes worth of love, inspiration and faith. 2 Acknowledgements My utmost gratitude goes first to my supervisors, Dr. Lisa Sabbahy, for her patience and support and Dr. Salima Ikram for her invaluable input. I would also like to thank Dr. Mariam Ayad for providing me with inspiration and having faith in my subject. My deepest gratitude goes to Dr. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY PERCEPTIONS OF ANCIENT EGYPT THROUGH HISTORY, ACQUISITION, USE, DISPLAY, IMAGERY, AND SCIENCE OF MUMMIES ANNA SHAMORY SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Archaeological Science and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies with honors in Archaeological Science Reviewed and approved* by the following: Claire Milner Associate Research Professor of Anthropology Thesis Supervisor Douglas Bird Associate Professor of Anthropology Honors Adviser * Electronic approvals are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT To the general public, ancient Egypt is the land of pharaohs, pyramids, and most importantly – mummies. In ancient times, mummies were created for a religious purpose. The ancient Egyptians believed that their bodies needed to be preserved after physical death, so they could continue into the afterlife. In the centuries after ancient Egypt fell to Roman control, knowledge about ancient Egyptian religion, language, and culture dwindled. When Egypt and its mummies were rediscovered during the Middle Ages, Europeans had little understanding of this ancient culture beyond Classical and Biblical sources. Their lack of understanding led to the use of mummies for purposes beyond their original religious context. After Champollion deciphered hieroglyphics in the 19th century, the world slowly began to learn about Egypt through ancient Egyptian writings in tombs, monuments, and artifacts. Fascination with mummies has led them to be one of the main sources through which people conceptualize ancient Egypt. Through popular media, the public has come to have certain inferences about ancient Egypt that differ from their original meaning in Pharaonic times. -

The Relationship Between the Badarian and the Amratian in Prehistoric Egypt

The Relationship between the Badarian and the Amratian in Prehistoric Egypt Justine J James Two Year Paper Stephen. Harvey Gil Stein March 2004 James 1 Introduction Despite over a century of research since Jacques de Morgan and W. M. F. Petrie made the first discovery and identification of prehistoric artifacts in Egypt, the prehistoric or Predynastic period, especially in the final 2000 or so years leading up to the historic period,1 is not clearly understood. One of the major questions still facing Egyptologists is the question of the origins of pharaonic civilization. Specifically, was pharaonic civilization the product of a gradual evolution of a single cultural antecedent in the Nile valley, the product of a combination of a number of different cultural antecedents in the Nile valley, the product of an entirely new culture whose origins are outside the Nile valley, or a combination of all of the above? Answering this question requires a clearer understanding of prehistoric cultures both in the Nile valley proper and in the surrounding deserts and south into the modern Sudan, especially in terms of chronology and geography. In an attempt to clarify one of these cultural relationships, this paper will focus on the Badarian and Amratian cultural units. The Badarian is traditionally described as a Neolithic farming culture dating to between 5000/4000 and 3900 BC focused in a 35 km strip of around 40 settlement areas in Middle Egypt along the Nile, despite finds of Badarian-like materials outside this presumed homeland at Hierakonpolis, Armant, and Wadi Hammamat.2 The Amratian is described as a Predynastic farming culture with a widespread presence in Upper Egypt spanning Matmar in the north to Wadi Kubbaniya in the south, dating to between 3900 and 3650 BC. -

In Early Egypt: Towards a Prehistoric Perspective on the Narmer Palette

Cambridge Archaeological Journal http://journals.cambridge.org/CAJ Additional services for Cambridge Archaeological Journal: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Rethinking ‘Cattle Cults’ in Early Egypt: Towards a Prehistoric Perspective on the Narmer Palette David Wengrow Cambridge Archaeological Journal / Volume 11 / Issue 01 / April 2001, pp 91 104 DOI: 10.1017/S0959774301000051, Published online: 05 September 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0959774301000051 How to cite this article: David Wengrow (2001). Rethinking ‘Cattle Cults’ in Early Egypt: Towards a Prehistoric Perspective on the Narmer Palette. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 11, pp 91104 doi:10.1017/S0959774301000051 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAJ, IP address: 144.82.107.37 on 30 Jan 2013 Cambridge Archaeological Journal 11:1 (2001), 91–104 Rethinking ‘Cattle Cults’ in Early Egypt: Towards a Prehistoric Perspective on the Narmer Palette David Wengrow The Narmer Palette occupies a key position in our understanding of the transition from Predynastic to Dynastic culture in Egypt. Previous interpretations have focused largely upon correspondences between its decorative content and later conventions of élite dis- play. Here, the decoration of the palette is instead related to its form and functional attributes and their derivation from the Neolithic cultures of the Nile Valley, which are contrasted with those of southwest Asia and Europe. It is argued that the widespread adoption of a pastoral lifestyle during the fifth millennium BC was associated with new modes of bodily display and ritual, into which cattle and other animals were incorporated. -

African Origins of International Law: Myth Or Reality? Jeremy I

Florida A&M University College of Law Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law Journal Publications Faculty Works 2015 African Origins of International Law: Myth or Reality? Jeremy I. Levitt Florida A&M University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.law.famu.edu/faculty-research Part of the African History Commons, International Law Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Jeremy I. Levitt, African Origins of International Law: Myth or Reality? 19 UCLA J. Int'l L. Foreign Aff. 113 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN ORIGINS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW: MYTH OR REALITY? Jeremy 1. Levitt.* ABSTRACT This Article reconsiders the prevalent ahistorical assumption that international law began with the Treaty of Westphalia. It gathers together considerable historical evidence to conclude that the ancient world, particularly the New Kingdom period in Egypt or Kemet from 1570-1070 BeE, deployed all three of what today we would call sources of international law. African states predating the modern European nation state by nearly 6000 years engaged in treaty relations (the Treaty of Kadesh), and applied rules ofcustom (the MA 'AT) andgeneral principles of law (as enumerated in the Egyptian Bill ofRights). While Egyptologists and a few international lawyers have acknowledged these facts, scholarly * Jeremy 1. Levitt, J.D., Ph.D., is Vice-Chancellor's Chair and former Dean, University of New Brunswick Law School. -

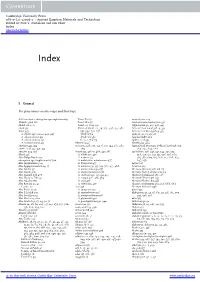

I General for Place Names See Also Maps and Their Keys

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-12098-2 - Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology Edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw Index More information Index I General For place names see also maps and their keys. AAS see atomic absorption specrophotometry Tomb E21 52 aerenchyma 229 Abbad region 161 Tomb W2 315 Aeschynomene elaphroxylon 336 Abdel ‘AI, 1. 51 Tomb 113 A’09 332 Afghanistan 39, 435, 436, 443 abesh 591 Umm el-Qa’ab, 63, 79, 363, 496, 577, 582, African black wood 338–9, 339 Abies 445 591, 594, 631, 637 African iron wood 338–9, 339 A. cilicica 348, 431–2, 443, 447 Tomb Q 62 agate 15, 21, 25, 26, 27 A. cilicica cilicica 431 Tomb U-j 582 Agatharchides 162 A. cilicica isaurica 431 Cemetery U 79 agathic acid 453 A. nordmanniana 431 Abyssinia 46 Agathis 453, 464 abietane 445, 454 acacia 91, 148, 305, 335–6, 335, 344, 367, 487, Agricultural Museum, Dokki (Cairo) 558, 559, abietic acid 445, 450, 453 489 564, 632, 634, 666 abrasive 329, 356 Acacia 335, 476–7, 488, 491, 586 agriculture 228, 247, 341, 344, 391, 505, Abrak 148 A. albida 335, 477 506, 510, 515, 517, 521, 526, 528, 569, Abri-Delgo Reach 323 A. arabica 477 583, 584, 609, 615, 616, 617, 628, 637, absorption spectrophotometry 500 A. arabica var. adansoniana 477 647, 656 Abu (Elephantine) 323 A. farnesiana 477 agrimi 327 Abu Aggag formation 54, 55 A. nilotica 279, 335, 354, 367, 477, 488 A Group 323 Abu Ghalib 541 A. nilotica leiocarpa 477 Ahmose (Amarna oªcial) 115 Abu Gurob 410 A. -

Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times

sustainability Review Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times Abdelkader T. Ahmed 1,2,* , Fatma El Gohary 3, Vasileios A. Tzanakakis 4 and Andreas N. Angelakis 5,6 1 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan 81542, Egypt 2 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Islamic University, Madinah 42351, Saudi Arabia 3 Water Pollution Research Department, National Research Centre, Cairo 12622, Egypt; [email protected] 4 Department of Agriculture, School of Agricultural Science, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Iraklion, 71410 Crete, Greece; [email protected] 5 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion, Greece; [email protected] 6 Union of Water Supply and Sewerage Enterprises, 41222 Larissa, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 October 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 Abstract: Egyptian and Greek ancient civilizations prevailed in eastern Mediterranean since prehistoric times. The Egyptian civilization is thought to have been begun in about 3150 BC until 31 BC. For the ancient Greek civilization, it started in the period of Minoan (ca. 3200 BC) up to the ending of the Hellenistic era. There are various parallels and dissimilarities between both civilizations. They co-existed during a certain timeframe (from ca. 2000 to ca. 146 BC); however, they were in two different geographic areas. Both civilizations were massive traders, subsequently, they deeply influenced the regional civilizations which have developed in that region. Various scientific and technological principles were established by both civilizations through their long histories. Water management was one of these major technologies. Accordingly, they have significantly influenced the ancient world’s hydro-technologies. -

The Upper Egyptian Naqada Culture Is Best Defined by Its Material

The Nile Delta as a centre of cultural interactions between Upper Egypt and the Southern Levant in the 4th millennium BC Studies in African Archaeology 13 oF pots And Myths – AtteMpting A coMpArAtive STUDY OF FUNERARY POttERY ASSEMBLAGES IN TH THE EGYPTIAN NILE VALLEY DURING THE LATE 4 1 MiLLenniuM bc. e. chrisTiANA köhler University of Vienna, Austria 1. introduction: questions And hypotheses The Upper Egyptian Naqada culture is best defined by its material remains found in the graves of the 4th Millennium BC., and in particular by the pottery deposited therein. Already fliNDers PeTrie used the various ceramic wares and their typological developments as a guide for his Sequence Dates upon which the relative chronology of that period was founded. This funerary pottery was also key to understanding the overall character and distribution of this culture along the Nile Valley in time and over time. Although not without early criticism (e.g. schArff 1926: 71-78), it had been suggested that this culture exhibited a remarkable uniformity over a stretch of hundreds of kilometres (kAiser 1957: 74; riZkANA & seeher 1987: 67; heNDrickx 1996: 63). Any observable changes in the ceramic assemblages were not only considered indicative of the progress of time, but also of more far-reaching cultural and social processes such as ethnic migrations or invasions (e.g. PeTrie & quibell 1896; PeTrie 1920; kAiser 1957). These concepts dominated the scholarly discourse of almost the entire 20th century. Only the last two decades of that century also saw the introduction of a more nuanced discussion when new and ever growing archaeological evidence, especially from the Nile Delta, started to cast shadows on these concepts, exposed their shortcomings and caused scholars to rethink traditional approaches.