Coping with the Army: the Military and the State in the New Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Study of the Inner Coffin and Mummy Cover Of

A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF THE INNER COFFIN AND MUMMY COVER OF NESYTANEBETTAWY FROM BAB EL-GUSUS (A.9) IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, WASHINGTON, D.C. by Alec J. Noah A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Art History The University of Memphis May 2013 Copyright © 2013 Alec Noah All rights reserved ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I must thank the National Museum of Natural History, particularly the assistant collection managers, David Hunt and David Rosenthal. I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr. Nigel Strudwick, for his guidance, suggestions, and willingness to help at every step of this project, and my thesis committee, Dr. Lorelei H. Corcoran and Dr. Patricia V. Podzorski, for their detailed comments which improved the final draft of this thesis. I would like to thank Grace Lahneman for introducing me to the coffin of Nesytanebettawy and for her support throughout this entire process. I am also grateful for the Lahneman family for graciously hosting me in Maryland on multiple occasions while I examined the coffin. Most importantly, I would like to thank my parents. Without their support, none of this would have been possible. iv ABSTRACT Noah, Alec. M.A. The University of Memphis. May 2013. A Preliminary Study of the Inner Coffin and Mummy Cover of Nesytanebettawy from Bab el-Gusus (A.9) in the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Major Professor: Nigel Strudwick, Ph.D. The coffin of Nesytanebettawy (A.9) was retrieved from the second Deir el Bahari cache in the Bab el-Gusus tomb and was presented to the National Museum of Natural History in 1893. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Piety, Practice, and Politics: Agency and Ritual in the Late Bronze Age Southern Levant Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8vx8j9v5 Author DePietro, Dana Douglas Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Piety, Practice, and Politics: Ritual and Agency in the Late Bronze Age Southern Levant By Dana Douglas DePietro A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Marian Feldman, Chair Professor Benjamin Porter Professor Aaron Brody Professor Margaret Conkey Spring 2012 © 2012- Dana Douglas DePietro All rights reserved. Abstract Piety, Practice, and Politics: Ritual and Agency in the Late Bronze Southern Levant by Dana Douglas DePietro Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Marian Feldman, Chair Striking changes in the archaeological record of the southern Levant during the final years of the Late Bronze Age have long fascinated scholars interested in the region and period. Attempts to explain the emergence of new forms of Canaanite material culture have typically cited external factors such as Egyptian political domination as the driving force behind culture change, relying on theoretical models of acculturation, elite-emulation and center-periphery theory. While these approaches can be useful in explaining some dimensions of culture-contact, they are limited by their assumption of a unidirectional flow of power and influence from dominant core societies to passive peripheries. -

In Ancient Egypt

THE ROLE OF THE CHANTRESS ($MW IN ANCIENT EGYPT SUZANNE LYNN ONSTINE A thesis submined in confonnity with the requirements for the degm of Ph.D. Graduate Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civiliations University of Toronto %) Copyright by Suzanne Lynn Onstine (200 1) . ~bsPdhorbasgmadr~ exclusive liceacc aiiowhg the ' Nationai hiof hada to reproduce, loan, distnia sdl copies of this thesis in miaof#m, pspa or elccmnic f-. L'atm criucrve la propri&C du droit d'autear qui protcge cette thtse. Ni la thèse Y des extraits substrrntiets deceMne&iveatetreimprimCs ouraitnmcrtrepoduitssanssoai aut&ntiom The Role of the Chmaes (fm~in Ancient Emt A doctorai dissertacion by Suzanne Lynn On*, submitted to the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations, University of Toronto, 200 1. The specitic nanire of the tiUe Wytor "cimûes", which occurrPd fcom the Middle Kingdom onwatd is imsiigated thrwgh the use of a dalabase cataloging 861 woinen whheld the title. Sorting the &ta based on a variety of delails has yielded pattern regatding their cbnological and demographical distribution. The changes in rhe social status and numbers of wbmen wbo bore the Weindicale that the Egyptians perceivecl the role and ams of the titk âiffefcntiy thugh tirne. Infomiation an the tities of ihe chantressw' family memkrs bas ailowed the author to make iderences cawming llse social status of the mmen who heu the title "chanms". MiMid Kingdom tifle-holders wverc of modest backgrounds and were quite rare. Eighteenth DMasty women were of the highest ranking families. The number of wamen who held the titk was also comparatively smaii, Nimeenth Dynasty women came [rom more modesi backgrounds and were more nwnennis. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

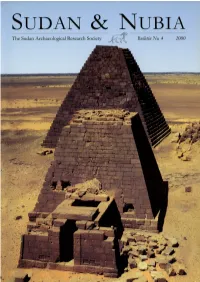

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Buhen in the New Kingdom

Buhen in the New Kingdom George Wood Background - Buhen and Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom Traditionally ancient Egypt ended at the First Cataract of the Nile at Elephantine (modern Aswan). Beyond this lay Lower Nubia (Wawat), and beyond the Dal Cataract, Upper Nubia (Kush). Buhen sits just below the Second Cataract, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Wadi Halfa, at what would have been a good location for ships to carry goods to the First Cataract. The resources that flowed from Nubia included gold, ivory, and ebony (Randall-MacIver and Woolley 1911a: vii, Trigger 1976: 46, Baines and Málek 1996: 20, Smith, ST 2004: 4). Egyptian operations in Nubia date back to the Early Dynastic Period. Contact during the 1st Dynasty is linked to the end of the indigenous A-Group. The earliest Egyptian presence at Buhen may have been as early as the 2nd Dynasty, with a settlement by the 3rd Dynasty. This seems to have been replaced with a new town in the 4th Dynasty, apparently fortified with stone walls and a dry moat, somewhat to the north of the later Middle Kingdom fort. The settlement seems to have served as a base for trade and mining, and royal seals from the 4th and 5th Dynasties indicate regular communications with Egypt (Trigger 1976: 46-47, Baines and Málek 1996: 33, Bard 2000: 77, Arnold 2003: 40, Kemp 2004: 168, Bard 2015: 175). The latest Old Kingdom royal seal found was that of Nyuserra, with no archaeological evidence of an Egyptian settlement after the reign of Djedkara. -

Demotic Dictionary Project

oi.uchicago.edu PHILOLOGY DEMOTIC DICTIONARY PROJECT Janet H.Johnson This year, as for the past several years, the Demotic Dictionary staff concentrated on checking drafts of entries for individual letters in the Egyptian "alphabet" and preparing and entering computer scan copies of the actual Demotic words. The only student work ing on the project this year was Thomas Dousa, whose command of Egyptian and Greek and the extensive literature in both has allowed him to make major contributions to the checking and rewriting of first draft entries. Thanks to a very generous bequest from Professor and Mrs. George R. Hughes, we anticipate being able next year to hire a recent Ph.D. graduate as Research Associate to work full time on checking of draft and preparation of scans and copies. The checking and rewriting of first draft entries involves double checking of all in formation provided in the entry and the incorporation of several categories of informa tion that we decided to include after the first drafts had been written. Many of these categories are being added to provide social or cultural information as part of the "meaning" of a word. For example, whenever the "word" is the name of a deity, a refer ence is provided to every geographic location (e.g., a specific city or cemetery) with which the deity is associated in the texts of the corpus from which the Chicago Demotic Dictionary is being drawn. Similarly, whenever the "word" being discussed is the name of a geographic location, reference is made to all deities mentioned in the texts of our corpus in conjunction with that geographic location. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Traveling Within Pharaonic Egypt for Discovering the Past

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE, Vol. 3, No. 1, (2017), pp. 15-21 Copyright © 2017 SC Open Access. Printed in Greece. All Rights Reserved. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.192840 TRAVELING WITHIN PHARAONIC EGYPT FOR DISCOVERING THE PAST Sherine El-Menshawy Qatar University, College of Arts and Sciences, Humanities Department, B.O. 2713, QU, Qatar Received: 24/10/2016 Accepted: 11/12/2016 ([email protected]) ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to assess to what degree were archaeological visits in ancient Egypt is regarded as visits of historical or touristical purpose. Research questions include: Who traveled, where and why? The accessibility of the visited places, the preferred season for such visits, the visitors‘ ethics in relation to the ancient monuments, the provisions carried with them and the preferable means of travel will be discussed. Evidence for those visits will be discussed, followed by analytical argument. KEYWORDS: Archaeological visits, category, motivations and ethics of visitors, carried provisions, means of travel. 16 S. EL-MENSHAWY 1. INTRODUCTION 2011; Navrátilová, 2013). Places and kings‘ names mentioned in the graffiti suggest that history and Archaeological visits have long existed in ancient geography were part of the New Kingdom scribes‘ Egypt, my aim is to assess to what extent were those education, where scribes were able to show their visits viewed as visits of historical or touristical knowledge about the former sovereigns by scrib- purpose? Much like contemporary times ancient bling their titles and names in the graffiti (Navrátilo- people travelled around for various purposes. The vá, 2011). A well-known scribe was Nebnetjeru who research attempts to answer further questions such left graffiti from Kalabsha and Dendur till Toshka as sites visited (where?), the identity of the ancient (Černý, 1947). -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'archéologie Orientale

MINISTÈRE DE L'ÉDUCATION NATIONALE, DE L'ENSEIGNEMENT SUPÉRIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE BULLETIN DE L’INSTITUT FRANÇAIS D’ARCHÉOLOGIE ORIENTALE en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne en ligne BIFAO 114 (2014), p. 455-518 Nico Staring The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara Conditions d’utilisation L’utilisation du contenu de ce site est limitée à un usage personnel et non commercial. Toute autre utilisation du site et de son contenu est soumise à une autorisation préalable de l’éditeur (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). Le copyright est conservé par l’éditeur (Ifao). Conditions of Use You may use content in this website only for your personal, noncommercial use. Any further use of this website and its content is forbidden, unless you have obtained prior permission from the publisher (contact AT ifao.egnet.net). The copyright is retained by the publisher (Ifao). Dernières publications 9782724708288 BIFAO 121 9782724708424 Bulletin archéologique des Écoles françaises à l'étranger (BAEFE) 9782724707878 Questionner le sphinx Philippe Collombert (éd.), Laurent Coulon (éd.), Ivan Guermeur (éd.), Christophe Thiers (éd.) 9782724708295 Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 30 Sylvie Marchand (éd.) 9782724708356 Dendara. La Porte d'Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724707953 Dendara. La Porte d’Horus Sylvie Cauville 9782724708394 Dendara. La Porte d'Hathor Sylvie Cauville 9782724708011 MIDEO 36 Emmanuel Pisani (éd.), Dennis Halft (éd.) © Institut français d’archéologie orientale - Le Caire Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 1 / 1 The Tomb of Ptahmose, Mayor of Memphis Analysis of an Early 19 th Dynasty Funerary Monument at Saqqara nico staring* Introduction In 2005 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acquired a photograph taken by French Egyptologist Théodule Devéria (fig. -

Who's Who in Ancient Egypt

Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Available from Routledge worldwide: Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt Michael Rice Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East Gwendolyn Leick Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in World Politics Alan Palmer Who’s Who in Dickens Donald Hawes Who’s Who in Jewish History Joan Comay, new edition revised by Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Who’s Who in Military History John Keegan and Andrew Wheatcroft Who’s Who in Nazi Germany Robert S.Wistrich Who’s Who in the New Testament Ronald Brownrigg Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, new edition revised by Alan Kendall Who’s Who in the Old Testament Joan Comay Who’s Who in Russia since 1900 Martin McCauley Who’s Who in Shakespeare Peter Quennell and Hamish Johnson Who’s Who in World War Two Edited by John Keegan Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Michael Rice 0 London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. © 1999 Michael Rice The right of Michael Rice to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Egypt and Africa Presentation.Pdf

Egypt and Africa Map of the Second Cataract showing fortress area Different plan types of Nubian fortresses: Cataract fortresses Plains fortresses Fortress at Buhen: Plains Fortress Defensive Characteristics Askut: Cataract Fort Middle Kingdom institutions as shown by seal impressions First Semna Stela of Senwosret III Southern boundary, made in the year 8, under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khakaure Senwosret III who is given life forever and ever; in order to prevent that any Nubian should cross it, by water or by land, with a ship or with any herds of the Nubians, except a Nubian who shall come to do trading in Iqen (Mirgissa) or with a commission. Every good thing shall be done with them, but without allowing a ship of the Nubians to pass by Heh, going downstream, forever. Boundary Stela of Senwosret III from Semna (a duplicate found at Uronarti) “…I have made my boundary further south than my fathers, I have added to what was bequeathed me. I am a king who speaks and acts, What my heart plans is done by my arm… Attack is valor, retreat is cowardice, A coward is he who is driven from his border. Since the Nubian listens to the word of mouth, To answer him is to make him retreat. Attack him, he will turn his back, Retreat, he will start attacking. They are not people one respects, They are wretches, craven-hearted… As for any son of mine who shall maintain this border which my majesty has made, he is my son, born to my majesty. -

Historiografski Problemi Kronologije Staroegipatske Povijesti U Hrvatskim Povijesnim Znanostima I Nastavi Povijesti

Mladen Tomorad Filozofski fakultet u Zagrebu Pregledni članak UDK: 930.24(32):930(497.5) Historiografski problemi kronologije staroegipatske povijesti u hrvatskim povijesnim znanostima i nastavi povijesti U članku autor raspravlja različite probleme vezane uz upotrebu staroegipatske kro- nologije u povijesnim znanostima. Posebno se analizira pojam datacija te daje pregled raznih metoda vremenskog određenja za arheološke nalaze, staroegipatske kronologije i računanje vremena kod starih Egipćana, podjela na dinastije te povijesnih izvora na kojima se sama kronologija zasniva. U posebnom poglavlju autor daje pregled upo- trebe raznih kronologija u povijesnim znanostima u Hrvatskoj od sredine 19. stoljeća do danas te njene upotrebe u udžbenicima povijesti. U završnom dijelu članka autor donosi novu kronologiju staroegipatske povijesti koja se zasniva na rezultatima naj- novijih istraživanja te za koju smatra da bi se trebala isključivo upotrebljavati u svim budućim povijesnim djelima. Ključne riječi: datacija, računanje vremena, kronologija, metode datiranja, Stari Egipat, faraon, dinastija, povijesni izvori, kronološke tablice 1. Datacija i metode datiranja arheoloških ostataka Svaka osoba koja se bavila izučavanjem arheološke građe zna da je jedan od najte- žih koraka prilikom znanstvene analize i obrade svakog predmeta odrediti njegovu starost. To je osobito teško u slučajevima naših vrlo starih predmeta koji se čuvaju u pojedinim muzejskim zbirkama jer je kontekst njihova nalaza najčešće nepoznat te su oni u razne institucije često stigli putem brojnih posrednika. Što je datacija? Pojam datacija (lat. datatio) znači da se svaki predmet mora sta- viti u neki vremenski kontekst, odrediti njegova starost, odnosno staviti ga u neke vremenske granice. Samo određenje starosti nalaza prilikom arheoloških iskapanja može biti relativno i apsolutno.