Egyptians Versus Kushites Florence Doyen, Luc Gabolde

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three “Italian” Graffiti from Semna and Begrawiya North

Eugenio Fantusati THREE “ITALIAN” GRAFFITI FROM SEMNA AND BEGRAWIYA NORTH Egyptian monuments are known to bear texts and composed of soldiers, explorers, merchants and, signatures engraved by Western travelers who in the second wave clerics, was quite consider- thus left traces of their passage on walls, columns able. For a long time the call of the exotic and of and statues beginning after the Napoleonic ex- adventure drew many Italians to Africa. In the pedition. early 19th century, they had no qualms about Sudan, although less frequented, did not leaving a fragmented country, not only governed escape this certainly depreciable practice. Indeed, by foreign powers, but also the theatre of bloody none of the European explorers in Batn el-Hagar wars for independence. Their presence in Africa avoided the temptation to leave graffiti on grew progressively to such an extent that Italian, archaeological sites, as if there was some myster- taught in Khartoum’s missionary schools, became ious force pushing them to this act, undeniable the commercial language of the Sudan. For a long because visible, once they had reached their so time, it was employed both in the official docu- longed-for destination. ments of the local Austrian consulate and in the Even George Alexander Hoskins, antiquarian, Egyptian postal service before being definitely writer and excellent draftsman, who openly supplanted by French after the opening of the condemned the diffusion of the practice to deface Suez Canal (Romanato 1998: 289). monuments, admitted his own “guilt” in this Naturally, the many Italians visiting archae- respect: “I confess on my first visit to the Nile, ological sites in Nubia did not refrain from I wrote my name on one of the colossal statues in leaving graffiti just like the other Europeans. -

The Semna South Project Louis V

oi.uchicago.edu The Semna South Project Louis V. Zabkar For those who have never visited the area of southern Egypt and northern Sudan submerged by the waters of the new Assuan High Dam, and who perhaps find it difficult to visualize what the "lake" created by the new Dam looks like, we include in this report two photographs which show the drastic geographic change which oc curred in a particular sector of the Nile Valley in the region of the Second Cataract. Before the flooding one could see the Twelfth Dynasty fortress; and, next to it, at the right, an extensive predominantly Meroitic and X-Group cemetery; the characteristic landmark of Semna South, the "Kenissa," or "Church," with its domed roof, built later on within the walls of the pharaonic fortress; the massive mud-brick walls of the fortress; and four large dumps left by the excavators—all this can be seen in the photo taken at the end of our excavations in April, 1968. On our visit there in April, 1971, the fortress was completely sub merged, the mud-brick "Kenissa" with its dome having collapsed soon after the waters began pounding against its walls. One can see black spots in the midst of the waters off the center which are the stones on the top of the submerged outer wall of the fortress. The vast cemetery is completely under water. In the distance, to the north, one can clearly see the fortress of Semna West, the glacis of which is also sub- 41 oi.uchicago.edu The area of Semna South included in our concession The Semna South concession submerged by the waters of the "lake 42 oi.uchicago.edu merged, and the brick walls of which may soon collapse through the action of the risen waters. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators this is max size of image at 200 dpi; the sil is low res and for the comp only. if approved, needs to be redone carefully American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts © 2006 American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs: Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum is organized by the American Federation of Arts and The British Museum. All materials included in this resource may be reproduced for educational American Federation of Arts purposes. 212.988.7700 800.232.0270 The AFA is a nonprofit institution that organizes art exhibitions for presen- www.afaweb.org tation in museums around the world, publishes exhibition catalogues, and interim address: develops education programs. 122 East 42nd Street, Suite 1514 New York, NY 10168 after April 1, 2007: 305 East 47th Street New York, NY 10017 Please direct questions about this resource to: Suzanne Elder Burke Director of Education American Federation of Arts 212.988.7700 x26 [email protected] Exhibition Itinerary to Date Oklahoma City Museum of Art Oklahoma City, Oklahoma September 7–November 26, 2006 The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens Jacksonville, Florida December 22, 2006–March 18, 2007 North Carolina Museum of Art Raleigh, North Carolina April 15–July 8, 2007 Albuquerque Museum of Art and History Albuquerque, New Mexico November 16, 2007–February 10, 2008 Fresno Metropolitan Museum of Art, History and Science Fresno, California March 7–June 1, 2008 Design/Production: Susan E. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

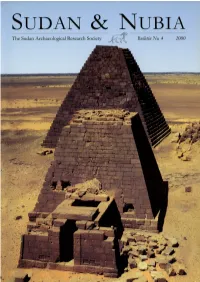

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Buhen in the New Kingdom

Buhen in the New Kingdom George Wood Background - Buhen and Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom Traditionally ancient Egypt ended at the First Cataract of the Nile at Elephantine (modern Aswan). Beyond this lay Lower Nubia (Wawat), and beyond the Dal Cataract, Upper Nubia (Kush). Buhen sits just below the Second Cataract, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite modern Wadi Halfa, at what would have been a good location for ships to carry goods to the First Cataract. The resources that flowed from Nubia included gold, ivory, and ebony (Randall-MacIver and Woolley 1911a: vii, Trigger 1976: 46, Baines and Málek 1996: 20, Smith, ST 2004: 4). Egyptian operations in Nubia date back to the Early Dynastic Period. Contact during the 1st Dynasty is linked to the end of the indigenous A-Group. The earliest Egyptian presence at Buhen may have been as early as the 2nd Dynasty, with a settlement by the 3rd Dynasty. This seems to have been replaced with a new town in the 4th Dynasty, apparently fortified with stone walls and a dry moat, somewhat to the north of the later Middle Kingdom fort. The settlement seems to have served as a base for trade and mining, and royal seals from the 4th and 5th Dynasties indicate regular communications with Egypt (Trigger 1976: 46-47, Baines and Málek 1996: 33, Bard 2000: 77, Arnold 2003: 40, Kemp 2004: 168, Bard 2015: 175). The latest Old Kingdom royal seal found was that of Nyuserra, with no archaeological evidence of an Egyptian settlement after the reign of Djedkara. -

Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: an Archaeological Note

Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies Volume 3 Know-Hows and Techniques in Ancient Sudan Article 3 2016 Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note Sebastien Maillot [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns Recommended Citation Maillot, Sebastien (2016) "Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note," Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies: Vol. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns/vol3/iss1/3 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 41 Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note Sébastien Maillot* The Kushite temples of Amun at Dukki Gel1 and Dangeil2 (fig. 1) fea- ture in their precincts large heaps of ash mixed with ceramic coni- cal moulds (or “bread moulds”), which are dumps associated with the production of food offerings for the cult. Excavation of the areas dedicated to these activities resumed in 2013 at both sites, uncover- ing numerous firing and storage features. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Applying a Multi- Analytical Approach to the Investigation of Ancient Egyptian Influence in Nubian Communities: The Socio- Cultural Implications of Chemical Variation in Ceramic Styles Julia Carrano Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Stuart T. Smith Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara George Herbst Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Gary H. Girty Department of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University Carl J. Carrano Department of Chemistry, San Diego State University Jeffrey R. Ferguson Archaeometry Laboratory, Research Reactor Center, University of Missouri Abstract is article reviews published archaeological research that explores the potential of combined chemical and petrographic analyses to distin - guish manufacturing methods of ceramics made om Nile river silt. e methodology was initially applied to distinguish the production methods of Egyptian and Nubian- style vessels found in New Kingdom and Napatan Period Egyptian colonial centers in Upper Nubia. Conducted in the context of ongoing excavations and surveys at the third cataract, ceramic characterization can be used to explore the dynamic role pottery production may have played in Egyptian efforts to integrate with or alter native Nubian culture. Results reveal that, despite overall similar geochemistry, x-ray fluorescence (XRF), instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA), and petrography can dis - tinguish Egyptian and Nubian- -

Part IV Historical Periods: New Kingdom Egypt to the Death of Thutmose IV End of 17Th Dynasty, Egyptians Were Confined to Upper

Part IV Historical Periods: New Kingdom Egypt to the death of Thutmose IV End of 17th dynasty, Egyptians were confined to Upper Egypt, surrounded by Nubia and Hyksos → by the end of the 18th dynasty they had extended deep along the Mediterranean coast, gaining significant economic, political and military strength 1. Internal Developments ● Impact of the Hyksos Context - Egypt had developed an isolated culture, exposing it to attack - Group originating from Syria or Palestine the ‘Hyksos’ took over - Ruled Egypt for 100 years → est capital in Avaris - Claimed a brutal invasion (Manetho) but more likely a gradual occupation - Evidence says Hyksos treated Egyptians kindly, assuming their gods/customs - Statues of combined godes and cultures suggest assimilation - STILL, pharaohs resented not having power - Portrayed Hyksos as foot stools/tiptoe as unworthy of Egyptian soil - Also realised were in danger of being completely overrun - Kings had established a tribune state but had Nubians from South and Hyksos from North = circled IMMEDIATE & LASTING IMPACT OF HYKSOS Political Economic Technological - Administration - Some production - Composite bow itself was not was increased due - Horse drawn oppressive new technologies chariot - Egyptians were - Zebu cattle suited - Bronze weapons climate better - Bronze armour included in the - Traded with Syria, - Fortification administration Crete, Nubia - Olive/pomegranat - Modelled religion e trees on Egyptians - Use of bronze - Limited instead of copper = disturbance to more effective culture/religion/d -

The Kingdom of Kush

Age of Empires Kush/ Nubia was an African Kingdom located to the south of Egypt Their close relationship with Egypt is evident on walls of Egyptian tombs and temples Next to Egypt, Kush was the greatest ancient civilization in Africa Kush was known for its rich gold mines Nub = gold in Egyptians Important trading hub Egyptian goods = grain, beer, linen Kush goods = gold, ivory, leather, timber Egypt often raided Kush and took control of parts of its territory Kush paid tribute to the pharaoh While under Egypt’s control, Kush became “Egyptianized” Kushites spoke Egyptian Worshipped same gods/goddesses Hired into the Egyptian Army Kush royal family was educated in Egypt After the collapse of the New Kingdom, there was a serious of weak and ineffective rulers causing Egypt to become extremely weak 730 B.C.E. Kush invaded and Egypt surrendered to King Piye Piye declared himself Pharaoh and “Uniter, of the Two Lands” Kushite pharaohs ruled Egypt for over 100 years Did not destroy Egyptian culture, but adapted Kushites were driven out by the Assyrians Meroe was safe out of Egypt's reach since they destroyed Napata (their previous capital) Important center of trade Production of iron Broke away from Egyptian tradition Had female leadership= kandakes or queen mothers Worshiped an African Lion god instead of Egyptian gods Story of Nubia www.youtube.com This short documentary tells the story of Nubia and the civilization that flourished in the Nile Valley for thousands of years and particularly between 800 BC and 400 .... -

The Nile: Evolution, Quaternary River Environments and Material Fluxes

13 The Nile: Evolution, Quaternary River Environments and Material Fluxes Jamie C. Woodward1, Mark G. Macklin2, Michael D. Krom3 and Martin A.J. Williams4 1School of Environment and Development, The University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK 2Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Wales, Aberystwyth, Aberystwyth SY23 3DB, UK 3School of Earth Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK 4Geographical and Environmental Studies, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia 13.1 INTRODUCTION et al., 1980; Williams et al., 2000; Woodward et al., 2001; Krom et al., 2002) as well as during previous interglacial The Nile Basin contains the longest river channel system and interstadial periods (Williams et al., 2003). The true in the world (>6500 km) that drains about one tenth of the desert Nile begins in central Sudan at Khartoum (15° African continent. The evolution of the modern drainage 37′ N 32° 33′ E) on the Gezira Plain where the Blue Nile network and its fl uvial geomorphology refl ect both long- and the White Nile converge (Figure 13.1). These two term tectonic and volcanic processes and associated systems, and the tributary of the Atbara to the north, are changes in erosion and sedimentation, in addition to sea all large rivers in their own right with distinctive fl uvial level changes (Said, 1981) and major shifts in climate and landscapes and process regimes. The Nile has a total vegetation during the Quaternary Period (Williams and catchment area of around 3 million km2 (Figure 13.1 and Faure, 1980). More recently, human impacts in the form Table 13.1).