Is There a Place for Religious Charter Schools? Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Hebrew Education in Public Schools

MAPPING HEBREW EDUCATION IN PUBLIC SCHOOLS: A Resource for Hebrew Educators WORKING PAPER SHARON AVNI AVITAL KARPMAN SEPTEMBER 2019 SEPTEMBER At the George Washington University’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development (GSEHD), we advance knowledge through meaningful research that improves the policy and practice of education. Together, more than 1,600 faculty, researchers and graduate students make up the GSEHD community of scholars. Founded in 1909, GSEHD continues to take on the challenges of the 21st century because we believe that education is the single greatest contributor to economic success and social progress. The Consortium for Applied Studies in Jewish Education (CASJE) is an evolving community of researchers, practitioners, and philanthropic leaders dedicated to improving the quality of knowledge that can be used to guide the work of Jewish education. The Consortium supports research shaped by the wisdom of practice, practice guided by research, and philanthropy informed by a sound base of evidence. AUTHORS Sharon Avni, PhD, CUNY (BMCC) Sharon Avni is Associate Professor of Language and Literacy in the Department of Academic Literacy and Linguistics at CUNY-BMCC. Avital Karpman, PhD, University of Maryland, College Park Avital Karpman is Associate Clinical Professor of Hebrew and Director of the Hebrew Program at the School of Languages, Literatures and Cultures at the University of Maryland, College Park. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We wish to acknowledge the substantial help and encouragement we received from Dr. Peter Friedman z”l of the Jewish United Fund of Metropolitan Chicago, who passed away before this report was completed. SUMMARY AND BACKGROUND In the past decade, there has been a resurgence in the study of Hebrew in traditional and charter public schools.1 However, the types of schools teaching Hebrew and the demographics of students studying Hebrew do not resemble those of earlier iterations of public school Hebrew programs that trace back to the early 20th century. -

HASHAVUA June 26, 2021 Shabbat Parshat Balak 16 Tammuz 5781

“ HASHAVUA June 26, 2021 Shabbat Parshat Balak 16 Tammuz 5781 YOUNG ISRAEL OF HOLLYWOOD-FT. LAUDERDALE 3291 Stirling Road | Ft. Lauderdale, Florida 33312 | 954.966.7877 | [email protected] | www.yih.org Rabbi Yosef Weinstock Rabbi Edward Davis Marc Ben-Ezra Senior Rabbi Rabbi Emeritus President Sephardic Minyan Rabbi Rabbi Adam Frieberg Assistant Rabbi Candle Lighting ....................... 7:58 PM Shabbat Ends ......................... 8:56 PM Torah Reading ............... Numbers 22:2 Haftorah ................................ Micah 5:6 Nach Yomi .......................... Proverbs 5 Daf Yomi ................................ Yoma 76 Daf Hashavua ................... Yevamot 57 WELCOME TO OUR Wishing everyone a SCHOLAR-IN- This week’s Hashavua Safe and Healthy RESIDENCE sponsored by Summer! RABBI DR. KENNETH Joey & Bonnie Betesh BRANDER Our YIH Family Esther Shayna bat Mazal Tov Refuah Shleimah Nechama Mintza (Isabella Zummo's mother), Feiga Joey & Bonnie Betesh on Please contact the shul Necha bat Pessel (Fay the marriage of their son office if someone on this Lerner), Henna bat Sara, Ralph to Molly Esses, list has, Baruch Hashem, Masha bat Ruth (Marcia daughter of Susan & Jack recovered Chonchol-Craig Barany’s Esses, and to grandmother Cholim: Avraham mother), Nechama Chaya Regina Saada and the Mordechai ben Kraindel bat Sima (Mimi Jankovits' entire family (Dr. Arnold Markoe, mother), Rivka bat Sarah, Rabbi Nosson Yishaya & Sharona Whisler's uncle), Rivkah Chaya bat Devora Noa Schwartz on the birth Binyamin Simcha ben (Reva Shapiro, daughter of of their daughter Gittel Rus Adina Minya (Binny Debbie & Sammy Shapiro), Ciment), Chaim Rafael ben Rivka bat Elka Libe (Mark Condolences Leah (Howard Rotterdam), Langer's sister), Sara Leah David HaKohen ben Esther bat Rochel (Cynthia Lynn Rochelle (& Mark) Daniels (Lev Kandinov’s father), Haber-Cheryl Hamburg’s on the loss of her mother, Eliyahu David ben Sara sister), Sara Leah bat our esteemed member, Baila (Dr. -

Christian Codex

OUR LADY OF SORROW (A collection of spiritual essays by Israel Shamir) Introduction Sit comfortably, put your glass down. Check your response: What statement would annoy you most: a. your mother is a whore, b. Christ never existed and Resurrection is a myth, c. Jews have too much power in the US. If you consider 'C', you have a problem. Even worse, you are a part of the problem. For a long while, it was the problem of Palestine, but since then, the Second Intifada, a confrontation of Native Palestinians with the Jewish state grew into the World War Three. Many developments in politics, art, culture, and religion – not only the war in the Holy Land and in the Middle East, but decline of Christianity, rise of the Right, advent of Globalisation are parts of the same problem. The war in Palestine can be terminated today by granting full equality of its Jewish and non-Jewish residents. Somehow this solution is not even discussed. The author would love to make a celebratory presentation of wonderful achievements of Jews, if it would cause them to embrace their Palestinian neighbours. However, this way was tried and failed spectacularly. In the author’s eyes, the Jewish hubris is the main obstacle to the solution, and that is why these essays are deconstructing Jewishness, trying to undermine all possible reasons for the hubris. This could be painful reading for his Jewish brothers and sisters intoxicated with success and trapped by mantra of Jewish martyrdom. But the Jewish exclusiveness has to be exorcised, in order to integrate Jews into the family of nations. -

Sector Agnosticism and the Coming Transformation of Education Law Nicole S

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 70 | Issue 1 Article 1 1-2017 Sector Agnosticism and the Coming Transformation of Education Law Nicole S. Garnett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Education Law Commons Recommended Citation Nicole S. Garnett, Sector Agnosticism and the Coming Transformation of Education Law, 70 Vanderbilt Law Review 1 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol70/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 70 JANUARY 2017 NUMBER 1 ARTICLES Sector Agnosticism and the Coming Transformation of Education Law Nicole Stelle Garnett* Over the past two decades, the landscape of elementary and secondary education in the United States has shifted dramatically, due to the emergence and expansion of privately provided, but publicly funded, schooling options (including both charterschools and private school choice devices like vouchers, tax credits, and educational savings accounts). This transformation in the delivery of K12 education is the result of a confluence of factors-discussed in detail below-that increasingly lead education reformers to support efforts to increase the number of high quality schools serving disadvantaged students across all three educationalsectors, instead of focusing exclusively on reforming urban public schools. As a result, millions of American children now attend privately operated, publicly funded schools. This rise in a "sector agnostic" education policy has profound implications for the state and federal constitutional law of education because it blurs the distinction between charter and private schools. -

Jan/Feb 2018

Temple Torat Emet TEKIAH January—February 2018 14 Tevet — 13 Adar 5778 A Word From Our Rabbi Dear Friends, I hope you have had the opportunity to enjoy some of the wonderful events we have shared the past few months. I was incredibly moved by the installation weekend, as well as Volunteer Shabbat and Veterans Shabbat, and look forward to creating more moving experiences together. Thank you to everyone who helped make it happen, both through leading and attending. We are approaching Tu B’Shevat, the holiday of the trees, this Janu- ary. As a child, I always celebrated by planting a tree in Israel with JNF; as I have grown up, I have learned more about the ecological message of Judaism. The classic midrash in this regard is that on the sixth day of creation, God took Adam and Eve on a walking tour of the Garden, and God said, “be very careful with my creation, for if you ruin it, there will be nobody to fix it.” As we celebrate the trees and all of creation, we can also challenge ourselves, ask ourselves how well we have taken care of God’s creation, and how we could do a better job trying to leave the natural world a better place than we found it. The next few months will be bustling with activity, and I am looking forward to celebrating together. When Moses asked Pharaoh to let the Jews go from Egypt, Pharaoh asked “who is going?” Moses’ reply was that “we will all go, young and old; we will go with our sons and daughters, our flocks and our herds, for we must observe the Lord’s festival” (Shemot 10:9); Pharaoh refused, and Moses went ahead with the plague of locusts. -

IN the PUBLIC SPHERE Contact from the EDITOR

CONTACT AUTUMN 2009/CHESHVAN 5770 VOLUME 12 NUMBER 1 THE JOURNAL OF THE STEINHARDT FOUNDATION FOR JEWISH LIFE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE contact FROM THE EDITOR AUTUMN 2009/CHESHVAN 5770 VOLUME 12 NUMBER 1 Eli Valley Editor IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE Erica Coleman Copy Editor he current chapter of the American Jewish story is Janet Mann Administration unique: Never before in Jewish history has a society Yakov Wisniewski been so receptive to Jewish culture, ideas and people. Design Director Here Jews experience not only tolerance, but THE STEINHARDT FOUNDATION FOR JEWISH LIFE T celebration. This has engendered a central paradox of the Jewish Michael H. Steinhardt Chairman engagement industry: the effort to entrance American Jews about Robert P. Aronson Jewish experiences might seem superfluous in an era in which America President Rabbi David Gedzelman itself affirms Jewish culture and values. Executive Vice President Rabbi Irving Greenberg How to respond to the challenges and opportunities of this paradox Founding President Jonathan J. Greenberg z”l might determine the success of Jewish engagement efforts. By now it Founding Director has become clear even to many who work inside the insular Jewish CONTACT is produced and distributed by The Steinhardt Foundation communal world that treating American society as a threat is not only for Jewish Life, 6 East 39th Street, 10th floor, New York, NY 10016. absurd, but out of touch with the experiences of the very Jews they All issues of Contact are available for download at www.steinhardtfoundation.org/journal.html seek to reach. The parallel paradox is that in some cases, American Individual subscriptions are free of charge and are provided as a service to the community. -

Directories Lists Obituaries National Jewish Organizations*

Directories Lists Obituaries National Jewish Organizations* UNITED STATES Organizations are listed according to functions as follows: Community Relations 515 Cultural 520 Israel-Related 527 Overseas Aid 540 Religious, Educational Organizations 542 Schools, Institutions 553 Social, Mutual Benefit 564 Social Welfare 566 Note also cross-references under these headings: Professional Associations 570 Women's Organizations 571 Youth and Student Organizations 572 Canada 572 COMMUNITY RELATIONS AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (1906). The Jacob Blaustein Building, 165 E. 56 St., AMERICAN COUNCIL FOR JUDAISM (1943). PO Box 9009, Alexandria, VA 22304. NYC 10022. (212)751-4000. FAX: (212) (703)836-2546. Pres. Alan V. Stone; 750-0326. Pres. Bruce M. Ramer; Exec. Exec. Dir. Allan C. Brownfeld. Seeks to Dir. David A. Harris. Protects the rights advance the universal principles of a Ju- and freedoms of Jews the world over; daism free of nationalism, and the na- combats bigotry and anti-Semitism and tional, civic, cultural, and social integra- promotes democracy and human rights tion into American institutions of for all; works for the security of Israel Americans of Jewish faith. Issues of the and deepened understanding between American Council for Judaism; Special In- Americans and Israelis; advocates public- terest Report. policy positions rooted in American de- *The information in this directory is based on replies to questionnaires circulated by the editors. 515 516 / AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK, 1998 mocratic values and the perspectives of Philadelphia, PA 19103. (215)204-1459 Jewish heritage; and enhances the creative FAX: (215)204-7784. E-mail: v2026r vitality of the Jewish people. Includes @vm.temple.edu. Jerusalem office: Jeru- Jacob and Hilda Blaustein Center for salem Center for Public Affairs. -

ANNUAL ASSESSMENT 2010 Executive Report No

ANNUAL ASSESSMENT 2010 Executive Report No. 7 Special In-Depth Chapters: Systematic Indicators of Jewish People Trends De-Legitimization and Jewish Youth in the Diaspora !e Impact of Political Shifts and Global Economic Developments on the Jewish People PROJECT HEAD Dr. Shlomo Fischer CONTRIBUTORS Avinoam Bar-Yosef, Sylvia Barack Fishman, Barry Geltman, Avi Gil, Inbal Hakman, Michael Herzog, Arielle Kandel, Yogev Karasenty, Judit Bokser Liwerant, Dov Maimon, Alberto Milkewitz, Yehudah Mirsky, Steven Popper, Shmuel Rosner, Avia Spivak, Shalom Solomon Wald EDITOR Rami Tal Editor Rami Tal Copyright © !e Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI) (Established by the Jewish Agency for Israel, Ltd.) Jerusalem 2011/5771 JPPI, Givat Ram Campus, P.O.B 39156, Jerusalem 91391, Israel Telephone: 972-2-5633356 | Fax: 972-2-5635040 | www.jppi.org.il All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without express written permission from the publisher. Printed and Distributed by the Jewish People Policy Institute Graphic Design: Lotte Design Cover Design: Shlomit Wolf, Lotte Design ISBN 978-965-7549-02-5 Annual Assessment 2010 - Table of Contents Foreword – Amb. Stuart Eizenstat 5 Major Developments and Policy Directions 9 Selected Indicators on World Jewry – 2010 17 1. A System of Indicators for Measuring the Well-Being of the Jewish People 19 2. Significant Global Developments & Challanges 2009-2010: Possible Implications for the Jewish People Developments in the Geopolitical Arena and their Possible Implications for Israel and the Jewish People 49 2010 – !e Triangular Relationship between Washington, Jerusalem and the Jewish Communities 71 Global Economic Changes: Implications for Israel and the Jewish People 83 Asia’s Rise: Implications for Israel and the Jewish People 107 Latin American Jewry Today 123 3. -

Directories Lists Obituaries National Jewish Organizations*

Directories Lists Obituaries National Jewish Organizations* UNITED STATES Organizations are listed according to functions as follows: Community Relations 583 Cultural 588 Israel-Related 595 Overseas Aid 608 Religious, Educational Organizations 610 Schools, Institutions 622 Social, Mutual Benefit 632 Social Welfare 634 Note also cross-references under these headings: Professional Associations 639 Women's Organizations 639 Youth and Student Organizations 640 Canada 640 COMMUNITY RELATIONS AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (1906). The Jacob Blaustein Building, 165 E. 56 St., AMERICAN COUNCIL FOR JUDAISM (1943). PO Box 9009, Alexandria, VA 22304. NYC 10022. (212)751-4000. FAX: (703)836-2546. Pres. Alan V. Stone; Exec. (212)750-0326. Pres. Bruce M. Ramer; Dir. Allan C. Brownfeld. Seeks to ad- Exec. Dir. David A. Harris. Protects the vance the universal principles of a Ju- rights and freedoms of Jews the world daism free of nationalism, and the over; combats bigotry and anti-Semitism national, civic, cultural, and social inte- and promotes democracy and human gration into American institutions of rights for all; works for the security of Is- Americans of Jewish faith. Issues of the rael and deepened understanding between American Council for Judaism; Special In- Americans and Israelis; advocates public- terest Report, (WWW.ACJNA.ORG) policy positions rooted in American de- *The information in this directory is based on replies to questionnaires circulated by the editors. Web site addresses, where provided, appear at end of entries. 583 584 / AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK, 1999 mocratic values and the perspectives of Campus, 1616 Walnut St., Suite 507 Jewish heritage; and enhances the creative Philadelphia, PA 19103. -

Ben Gamla Charter School North Campus Location Number: #5001

Name of Charter School Seeking Renewal: Ben Gamla Charter School North Campus Location Number: #5001 Page 1 of 443 Name of Charter School Seeking Renewal: Ben Gamla Charter School North Campus Location Number: #5001 Broward County Public Schools Charter School Renewal: Indicators and Standards In accordance with section 1002.33(7)(a)(19)(b)(1), Florida Statutes, a charter school may be renewed provided that a program review demonstrates that the school has successfully fulfilled the terms of its contract [1002.33(7)(a)(19)]. Pursuant to section 1002.33(8)(a), Florida Statutes, “the sponsor shall make student academic achievement for all students the most important factor when determining whether to renew or terminate the charter.” In conducting a renewal program review, the sponsor will focus its analysis on the school’s performance in three categories: • Educational performance • Financial performance • Organizational performance The following defines specific indicators (the types and level of information and data that will be collected) and standards (the benchmark by which such indicators will be measured) that will be analyzed and evaluated within these three categories. It is a school’s performance within these indicators in addition to potential on-site specific programmatic reviews that inform a charter renewal decision. Furthermore, should a charter school meet the standards for renewal, The School Board of Broward County, Florida, will also review future Educational, Financial and Organizational plans submitted as part of this documentation for the term of its subsequent contract. Any modifications/adjustments/amendments proposed to the current contract that would take effect over the subsequent contract term may be negotiated during the contract phase. -

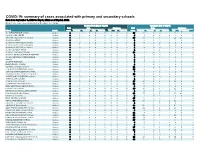

Weekly School Report.Xlsx

COVID-19: summary of cases associated with primary and secondary schools Data from September 6, 2020 to May 8, 2021 as of May 14, 2021 Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Previous Week (May 2 - May 8) Cumulative (Sep 6 - May 8) Total RoleSymptoms Total Role Symptoms School County cases Students Teachers Staff Unknown Yes No Unknowncases Students Teachers Staff Unknown Yes NoUnknown A. L. MEBANE MIDDLE SCHOOL Alachua 1 1 00 010 0 13 12 00 1112 0 A.QUINN JONES CENTER Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 4 1 11 130 1 ABRAHAM LINCOLN MIDDLE SCHOOL Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 37 29 44 02214 1 ALACHUA ACADEMY Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 1 0 10 010 0 ALACHUA COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 2 0 00 220 0 ALACHUA COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 1 0 00 110 0 ALACHUA COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 1 0 00 110 0 ALACHUA DISTRICT OFFICE Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 1 0 01 010 0 ALACHUA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 10 8 10 164 0 ALACHUA LEARNING ACADEMY ELEMENTARY Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 1 1 00 010 0 ALACHUA LEARNING ACADEMY MIDDLE Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 4 4 00 040 0 AMIKIDS Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 2 2 00 020 0 ARCHER ELEMENTARY Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 6 4 01 160 0 BHAKTIVEDANTA ACADEMY Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 1 0 10 010 0 BOULWARE SPRINGS CHARTER Alachua 0 0 00 000 0 11 7 21 183 0 C. -

Preserving a Critical National Asset: America's Disadvantaged Students

Preserving a Critical National Asset America’s Disadvantaged Students and the Crisis in Faith-based Urban Schools The White House Domestic Policy Council The nonpublic school situation: enrollments are falling and costs are climbing…If decline continues, pluralism in education will cease, parental options will virtually terminate, and public schools will have to absorb millions of American students. The greatest impact will be on…large urban centers, with especially grievous consequences for poor and lower middle-class families in racially changing neighborhoods where the nearby nonpublic school is an indispensable stabilizing factor. —President’s Panel on Nonpublic Education April 14, 1972 America’s inner-city faith-based schools are facing a crisis. And I use the word “crisis” for this reason: Between 2000 and 2006, nearly 1,200 faith-based schools closed in America’s inner cities. It’s affected nearly 400,000 students…We have an interest in the health of these centers of excellence; it’s in the country’s interest to get beyond the debate of public/ private, to recognize this is a critical national asset. —President George W. Bush April 24, 2008 Preserving a Critical National Asset America’s Disadvantaged Students and the Crisis in Faith-based Urban Schools The White House Domestic Policy Council September 2008 U.S. Department of Education Margaret Spellings Secretary September 2008 This report is in the public domain. Authorization to reproduce it in whole or in part is granted. While permission to reprint this publication is not necessary, the citation should be: U.S. Department of Education, Preserving a Critical National Asset: America’s Disadvantaged Students and the Crisis in Faith-based Urban Schools, Washington, D.C., 2008.