Major Roy Lower, Luftwaffe Tactical Operations at Stalingrad, Air War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kungl Örlogsmanna Sällskapet

KUNGL ÖRLOGSMANNA SÄLLSKAPET N:r 1 1973 TIDSKRIFT I SJÖVÅSENDET FöRSTA UTGIVNINGSAR 1836 KUNGL öRLOGSMANNASÄLLSKAPET KARLSKRONA POSTGIRO 12517-3 Huvud-Redaktör och ansvarig utgivare: överstelöjtnant J. O L SEN, 371 00 Karlskrona, telefon 0455/122 50. Redaktör: Kommendörkapten B. O D I N, Rigagatan 6, 115 27 Stockholm ö, telefon 08/60 32 25. Annonsombud: Redaktör R. B L O M, Fack 126 06 Hägersten 6, telefon 08/97 68 84. Tidskrift i Sjöväsendet utkommer med ett häfte i månaden. Prenumerations pris fr. o. m. 1.1.1968 25 kronor per år, i utlandet 30 kronor. Prenumeration sker enklast genom att avgiften insättes på postgirokonto 125 17-3. Inbetalningskort utsändes med januarihäftet. Förfrågningar angående kostnader m m för annonsering ställas direkt till huvudredaktören. Införda artiklar, recensioner o dyl honoreras med 12-25 kronor per sida. För införd artikel, som av KöS anses särskilt förtjänt kan författare belönas med sällskapets medalj och/eller prispenning. Bestämmelser för Kungl. örlogsmannasällskapets tävlingsskrifter återfinnas årligen i alla häften med udda månadsn:r. TIDSKRIFT SJOVÄSENDET 136 årgången 1 och 2 häftet INNEHÅLL Sid Meddelande från Kungl. Örlogsmannasällskapet nr 6/1972 l Meddelande från Kungl. örlogsmannasällskapet nr 7/1972 3 Tyskt-italienskt gästspel på Ladoga 1942 5 Av civilekonom P. O. EKMAN Projektering av övervattensfartyg ................................... 47 Av marindirektör P. G. BöLIN "Den ryska klockan" ............................................. 69 Av professor JACOB SUNDBERG Marin eldledning S ~~gkraft e n h ~s v~~ · a . rnarinn e nhe ter beror i e ldl edningssyste~1 utvecklats. som visa i sig nå goda totalprestanda o-.: h hög funktions- Notiser från när och fjärran 97 bog grad på effektiviteten hos deras vapen- k?nkurr.e nskrafuga även utomlands. -

List of Some of the Officers ~~10 Fall Within the Definition of the German

-------;-:-~---,-..;-..............- ........- List of s ome of t he officers ~~10 fall within t he de finition of t he German St af f . in Appendix B· of t he I n cii c tment . 1 . Kei t e l - J odl- Aar l imont 2 . Br auchi t s ch - Halder - Zei t zl er 3. riaeder - Doeni t z - Fr i cke - Schni ewi nd - Mei s el 4. Goer i ng - fu i l ch 5. Kes s el r i ng ~ von Vi et i nghof f - Loehr - von ~e i c h s rtun c1 s t ec t ,.. l.io d eL 6. Bal ck - St ude nt - Bl a skowi t z - Gud er i an - Bock Kuchl er - Pa ul us - Li s t - von Manns t ei n - Leeb - von Kl e i ~ t Schoer ner - Fr i es sner - Rendul i c - Haus s er 7. Pf l ug bei l - Sper r l e - St umpf - Ri cht hof en - Sei a emann Fi ebi £; - Eol l e - f)chmi dt , E .- Des s l och - .Christiansen 8 . Von Arni m - Le ck e ris en - :"emelsen - l.~ a n t e u f f e l - Se pp . J i et i i ch - 1 ber ba ch - von Schweppenburg - Di e t l - von Zang en t'al kenhol's t rr hi s' list , c ompiled a way f r om books and a t. shor t notice, is c ertai nly not a complete one . It may also include one or t .wo neop .le who have ai ed or who do not q ual ify on other gr ounds . -

Zarasai, Litnuania [email protected] DATE LOCATION ACTIVITY CHAIN of COMMAND 163

162 290. INFANTtRIE-DIVISION - UNIT HISTORY LOCATION ACTIVITY CHAIN OF COMMAND 1940/02/01 Tr.Ueb.Pl. monster, Wenrkreis X, Activation (8. Welle), Subordinate to: Stellv.Gen.Kdo. X, 1940/02/01-1940/05/16 Soltau, Fallingbostel, iibstorf, formation, training C.O.: Gen.Lt. Max uennerlein, 1940/02/06-1940/06/09 Schneveraingen, Bergen, WenrKr. XI (source: situation maps of Lage West ana general officer personnel files) 1940/05/10 Operational readiness 1940/05/14 Schnee citei Transfer Subordinate to: AK 38, 1940/05/17-1940/05/20 1940/05/19 Reuland, Weisstoampach, Saint- Movement AK 42, 1940/05/21-1940/05/23 Hubert, Libin, Gedinne, Belgium 1940/05/24 Kevin, Any, Origny-en-Thieracne, Movement, AK 38, 1940/05/24 Vervins, Sains- Ricnauinont, offensive engagements AK 42, 1940/05/25-1940/06/02 Saint-^uentin, Venaeuil, Laon, AK 18, 1940/06/03-1940/07/08 Oise-Aisne Canal, Soissons, wezy, Chateau-Tiiierry, Nangis, Montargis, CoO.: Gen.Lt. Theodor Frhr. von Wrede, 1940/06/08-1942/07/01 Bieneau, Gien, France 1940/00/21 Bieneau, Gien Offensive engagements 1940/07/01 Cnateauoriant, La Baule, Blois, Coastal defense, 1940/10/10 Neung, Vivy, floyetut, Anders, security, Saint-i>iazaire, Nantes occupation duty, training (no records for I940/0o/21-l941/01/31, source: situation maps of Lage West) 1941/02/01 La iiaule, Cnateaubriant, Nantes Coastal defense, security Subordinate to: AK 25, 1941/02/01-1941/02/28 1941/02/25 Gruuziadz, Poland Transfer, training AK 1, 1941/03/01-1941/03/15 AK 2, 1941/03/16-1941/03/31 1941/04/08 Elbing, Wormditt (Orneta), Movement, AK -

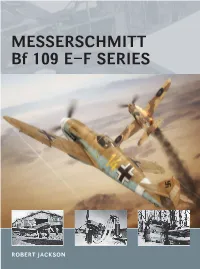

Messerschmitt Bf 109 E–F Series

MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON 19/06/2015 12:23 Key MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109E-3 1. Three-blade VDM variable pitch propeller G 2. Daimler-Benz DB 601 engine, 12-cylinder inverted-Vee, 1,150hp 3. Exhaust 4. Engine mounting frame 5. Outwards-retracting main undercarriage ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND ILLUSTRATOR 6. Two 20mm cannon, one in each wing 7. Automatic leading edge slats ROBERT JACKSON is a full-time writer and lecturer, mainly on 8. Wing structure: All metal, single main spar, stressed skin covering aerospace and defense issues, and was the defense correspondent 9. Split flaps for North of England Newspapers. He is the author of more than 10. All-metal strut-braced tail unit 60 books on aviation and military subjects, including operational 11. All-metal monocoque fuselage histories on famous aircraft such as the Mustang, Spitfire and 12. Radio mast Canberra. A former pilot and navigation instructor, he was a 13. 8mm pilot armour plating squadron leader in the RAF Volunteer Reserve. 14. Cockpit canopy hinged to open to starboard 11 15. Staggered pair of 7.92mm MG17 machine guns firing through 12 propeller ADAM TOOBY is an internationally renowned digital aviation artist and illustrator. His work can be found in publications worldwide and as box art for model aircraft kits. He also runs a successful 14 13 illustration studio and aviation prints business 15 10 1 9 8 4 2 3 6 7 5 AVG_23 Inner.v2.indd 1 22/06/2015 09:47 AIR VANGUARD 23 MESSERSCHMITT Bf 109 E–F SERIES ROBERT JACKSON AVG_23_Messerschmitt_Bf_109.layout.v11.indd 1 23/06/2015 09:54 This electronic edition published 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain in 2015 by Osprey Publishing, PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA E-mail: [email protected] Osprey Publishing, part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc © 2015 Osprey Publishing Ltd. -

Nazi Ideology and the Pursuit of War Aim: 1941-45

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Winter 2014 Nazi Ideology and the Pursuit of War Aim: 1941-45 Kenneth Burgess Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Burgess, Kenneth, "Nazi Ideology and the Pursuit of War Aim: 1941-45" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1204. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1204 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Jack N. Averitt College of Graduate Studies Electronic Theses & Dissertations (COGS ) Winter 2014 NAZI IDEOLOGY AND THE PURSUIT OF WAR AIMS: 1941-45. Kenneth B. Burgess II 1 NAZI IDEOLOGY AND THE PURSUIT OF WAR AIMS: 1941-45 by KENNETH BERNARD BURGESS II (UNDER DIRECTION OF BRIAN K. FELTMAN) ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to examine what can be considered a military blunder on the part of the Nazi Germans. On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany launched a massive invasion into the Soviet Union and Soviet territories. The political goals of Operation Barbarossa were to seize hold of the expanses of land belonging to the Soviet Union. This would serve as the foundation for increased agricultural production and the enslavement of any remaining Slavic people for the supposed greater good Germany. -

Denmark and the Holocaust

Denmark and the Holocaust Edited by Mette Bastholm Jensen and Steven L. B. Jensen Institute for International Studies Department for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Denmark and the Holocaust Edited by Mette Bastholm Jensen and Steven L. B. Jensen Institute for International Studies Department for Holocaust and Genocide Studies © Institute for International Studies, Department for Holocaust and Genocide Studies 2003 Njalsgade 80, 17. 3 2300 København S Tlf. +45 33 37 00 70 Fax +45 33 37 00 80 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.dchf.dk Denmark and the Holocaust Print: Werks Offset A/S, Bjødstrupvej 2-4, 8270 Højbjerg Editors: Mette Bastholm Jensen and Steven L. B. Jensen Translations: Gwynneth Llewellyn and Marie Louise Hansen-Hoeck Layout: Jacob Fræmohs ISSN 1602-8031 ISBN 87-989305-1-6 Preface With this book the Department for Holocaust and Genocide Studies publishes the third volume in the Danish Genocide Studies Series – a series of publications written or edited by researchers affiliated with the Department and its work on the Holocaust and genocide in general, along with studies of more specifically Danish aspects of the Holocausts. I extend my thanks to all the contributors to this volume, as well as Gwynneth Llewellyn and Marie Louise Hansen-Hoeck for their transla- tion work, Rachael Farber for her editorial assistance, and Jacob Fræmohs for devising the layout of the book. Finally, I would like to thank Steven L. B. Jensen and Mette Bastholm Jensen for planning and editing this publication. Uffe Østergård Head of Department, Department for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Institute for International Studies Copenhagen, April 2003 Table of Contents Introduction............................................................................................................ -

Dispatches BAKERSFIELD CA PERMIT NO 66 from Decision Games #39 FALL 2020

PRESRT STD US POSTAGE PAID DISPATCHES BAKERSFIELD CA PERMIT NO 66 FROM DECISION GAMES #39 FALL 2020 (661) 587-9633 | (661) 587-5031 fax | P.O. Box 21598 | Bakersfield CA 93390 | DECISIONGAMES.COM Excerpt from Strategy & Tactics #50 The Last Strategies By Stephen B. Patrick Germany By December, 1944, the Axis existed only in Hitler’s mind. Accordingly, all strategies were Hitler’s. Germany was fighting on four fronts by this time: the west, Italy, Poland and the Balkans. The last two were nominally one front, but, because the two Soviet drives were basically independent, they had to be treated separately. Hitler’s strategy, such as it was, was one of desperation and wishful thinking. He was convinced that the Anglo-American alliance with the Soviets could not endure. Subsequent events proved him right. What he failed to recognize was that the mutual hatred they bore for Nazism was sufficient to hold the alliance together for the duration of the war. Hitler seemed to have few illusions about Germany’s chances to win the war. He now wanted to settle for destroying Communism. Hitler convinced himself that he could work out an alliance with the Anglo- Americans and the three would then crush the Bolshevik menace. To “encourage” the British and American governments to see things his way, Hitler felt he needed a major victory in the west. He may not have seriously believed he could root the western Allies, but he did expect to deliver a blow that would seriously upset the western timetable. He also hoped to so upset morale at home in the western alliance that the German Panzer V Panther on the Eastern Front, 1944. -

Numbered Luftwaffe Formations and Assigned Units 1939-1945

Numbered Luftwaffe Formations and Assigned Units 1939-1945 Luftflotte 1: Formed on 2/1/39, upon mobilization it was assigned the following units: 10th Aufklärungsgruppe (Reconnaissance Group) 11th Aufklärungsgruppe 21st Aufklärungsgruppe 31st Aufklärungsgruppe 41st Aufklärungsgruppe 120th Aufklärungsgruppe 121st Aufklärungsgruppe 1/1st Jägergruppe (Fighter Group) Staff/,1/2nd Jägergruppe Staff/,1/3rd Jägergruppe 1/,2/1st Zerstörergruppe 1/2nd Zerstörergruppe (Destroyer Group equipped with Me-110) 1/1st Sturzkampfgruppe (Stuka Group) 1/,2/,3/2nd Sturzkampfgruppe 1st Luftnachrichten (Luftwaffe Signals) Regiment In 1939 during the Polish campaign, it had the Luftwaffe Training Division and the 1st Flieger Division. During the French campaign it remained in the East and did not participate in the war with France. During the invasion of Russia it commanded the I Fliegerkorps and the VIII Flieger Corps (only in July-September). In 1942, in Northern Russian, it provided material to the Demjansk Pocket using the Lufttransportführer (Formerly in Luftflotte 2). It had a number of flak formations assigned and they were: 2nd Flak Division (from January 1942 to September 1944 when it was sent to the west). 6th Flak Division (from April 1942) On 8/26/42 the Generalkommando I Fliegerkorps was transferred out and replaced by the 1st Fliegerführer, which in 1942 became the 3rd Flieger Division. During 1944 it continued in Russia, commanding the: 3rd Flieger Division Jagdabschnittsführer Ostland (April 1944, disbanded 9/17/44) Gefechtsverband Kulmey (only at the end of June) At the beginning of November the flying units assigned to its command were transferred to Luftwaffekommando West. Only the flak formations remained. -

British, Russian and World Orders, Medals and Decorations

British, Russian and World Orders, Medals and Decorations To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Day of Sale: Monday 30 November 2009 at 10.30 am and 2 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Wednesday 25 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Thursday 26 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Friday 27 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Please note that early viewing is encouraged. Catalogue no. 40 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton or Paul Wood Cover illustrations: Lot 1312 (front); Lot 1046 (back); Lots 1228, 1301 (inside front); ex Lot 1368 (inside back) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The actual hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed “starting prices”. A Buyer’s Premium of 15% is applicable to all lots in this sale. -

4Th Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division Polizei 1

4th Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division Polizei 1 1/263 4th Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division Polizei 2 ATENAS EDITORES ASOCIADOS 1998-2016 www.thegermanarmy.org Tittle: 4th Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division Polizei © Atenas Editores Asociados 1998-2016 © Gustavo Urueña A www.thegermanarmy.org More information: http://www.thegermanarmy.org First Published: September 2016 We include aditional notes and text to clarify original and re- produce original text as it in original book All right reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmited in any form or by any mens, electronic, mechanical, photocopyng or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the autor or publisher. Design: Atenas Editores Asociados 1998-2016 © Atenas Editores Asociados 1998-2016 The Editors welcome all comments and observations: [email protected] 2/263 4th Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division Polizei 3 3/263 4th Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division Polizei 4 4/263 4th Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division Polizei 5 5/263 4th Waffen SS Panzergrenadier Division Polizei 6 Alfred Wünnenberg Dates: * 20. July 1891, Saarburg ( Lothringen) - † 30. Decem- ber 1967, Krefeld / NRW An SS-Obergruppenführer und General der Waffen SS und Polizei and the commander of the 4th SS Polizei Panzer Gre- nadier Division during World War II who was awarded the Knight's Cross with Oakleaves. World War I Alfred Wünnenberg was born on 20 July 1891 at Saarburg/ Sarrebourg, Alsace-Lorraine, Germany. In February 1913 he joined the army and served in the 56th Infantry Regiment and was soon promoted to Unteroffizier. Alfred Wünnenberg was a company commander in Infantry Regiment 255 and later flyer observers during the First World War. -

Verbände Und Truppen Der Deutschen Wehrmacht Und Waffen SS Im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945

GEORG TESSIN Verbände und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen SS im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945 DRITTER BAND: Die Landstreitkräfte 6—14 Bearbeitet auf Grund der Unterlagen des Bundesarchiv-Militärarchivs Herausgegeben mit Unterstützung des Bundesarchivs und des Arbeitskreises für Wehrforschung VERLAG E. S. MITTLER & SOHN GMBH. • FRANKFURT/MAIN Vorwort zum 111. Band Die Herausgabc dieses bereits für 1966 geplanten Bandes hat sich durch den Tod des Verlegers verzögert. Es ist für mich ein tief gefühltes Bedürfnis, auch an dieser Stelle Herrn Dr. jur. Wilhelm Reibert, Oberst a. D. zu gedenken, der in seiner nimmermüden Einsatzbereitschaft für das militärische Schrift tum es übernommen hatte, dieses im Satz teure, im Absatz beschränkte und doch so notwendige Werk in einer des Verlages E. S. Mittler & Sohn würdigen Weise heraus zubringen. Bisher unbekannte, ungeordnet aus England zurückgekommene Akten des Ober kommandos der Luftwaffe in der Dokumentenzentrale des Militärgeschichtlichen Forschungsamtes in Freiburg brachten jetzt, 22 Jahre nach Kriegsende, wichtige Einzel heiten für die letzten Kriegsmonate, die in die kommenden Bände eingearbeitet, fin Band II und III jedoch nur nachträglich als Ergänzung hinzugefügt werden können. Mit der Herausgabe des I. Bandes dieses Werks, der außer den obersten Kommando behörden auch eine zusammenfassende Organisationsgeschichte nach Waffengattungen bringen wird, kann erst nach Fertigstellung des ganzen Manuskripts gerechnet werden Er wird bei der Herausgabe dann eingeschoben werden. Georg Tessin StadtbUcherei 47 Hamm 672794 ALLE RECHTE VORBEHALTEN COPYRIGHT BY E. S. MITTLER k SOHN GMBH, FRANKFURT/M. GESAMTHERSTELLUNG: H. G. CACHET * CO, LANGEN BEI FRANKFURT/M Gliederung Gliederung Sämtliche Verbände und Einheiten der Landstreitkräfte des Heeres, der Kriegsmarine, Luftwaffe und Waffen-SS sind in / Nummernfolge geordnet. -

Luftwaffe Maritime Operations in World War Ii

AU/ACSC/6456/2004-2005 AIR COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE AIR UNIVERSITY LUFTWAFFE MARITIME OPERATIONS IN WORLD WAR II: THOUGHT, ORGANIZATION AND TECHNOLOGY by Winston A. Gould, Major, USAF A Research Report Submitted to the Faculty In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements Instructor: Dr Richard R. Muller Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2005 Distribution A: Approved for Public Release; Distribution is Unlimited Ú±®³ ß°°®±ª»¼ λ°±®¬ ܱ½«³»²¬¿¬·±² п¹» ÑÓÞ Ò±ò ðéðìóðïèè Ы¾´·½ ®»°±®¬·²¹ ¾«®¼»² º±® ¬¸» ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±² ·• »•¬·³¿¬»¼ ¬± ¿ª»®¿¹» ï ¸±«® °»® ®»•°±²•»ô ·²½´«¼·²¹ ¬¸» ¬·³» º±® ®»ª·»©·²¹ ·²•¬®«½¬·±²•ô •»¿®½¸·²¹ »¨·•¬·²¹ ¼¿¬¿ •±«®½»•ô ¹¿¬¸»®·²¹ ¿²¼ ³¿·²¬¿·²·²¹ ¬¸» ¼¿¬¿ ²»»¼»¼ô ¿²¼ ½±³°´»¬·²¹ ¿²¼ ®»ª·»©·²¹ ¬¸» ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±²ò Í»²¼ ½±³³»²¬• ®»¹¿®¼·²¹ ¬¸·• ¾«®¼»² »•¬·³¿¬» ±® ¿²§ ±¬¸»® ¿•°»½¬ ±º ¬¸·• ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±²ô ·²½´«¼·²¹ •«¹¹»•¬·±²• º±® ®»¼«½·²¹ ¬¸·• ¾«®¼»²ô ¬± É¿•¸·²¹¬±² Ø»¿¼¯«¿®¬»®• Í»®ª·½»•ô Ü·®»½¬±®¿¬» º±® ײº±®³¿¬·±² Ñ°»®¿¬·±²• ¿²¼ λ°±®¬•ô ïîïë Ö»ºº»®•±² Ü¿ª·• Ø·¹¸©¿§ô Í«·¬» ïîðìô ß®´·²¹¬±² Êß îîîðîóìíðîò λ•°±²¼»²¬• •¸±«´¼ ¾» ¿©¿®» ¬¸¿¬ ²±¬©·¬¸•¬¿²¼·²¹ ¿²§ ±¬¸»® °®±ª·•·±² ±º ´¿©ô ²± °»®•±² •¸¿´´ ¾» •«¾¶»½¬ ¬± ¿ °»²¿´¬§ º±® º¿·´·²¹ ¬± ½±³°´§ ©·¬¸ ¿ ½±´´»½¬·±² ±º ·²º±®³¿¬·±² ·º ·¬ ¼±»• ²±¬ ¼·•°´¿§ ¿ ½«®®»²¬´§ ª¿´·¼ ÑÓÞ ½±²¬®±´ ²«³¾»®ò ïò ÎÛÐÑÎÌ ÜßÌÛ íò ÜßÌÛÍ ÝÑÊÛÎÛÜ ßÐÎ îððë îò ÎÛÐÑÎÌ ÌÇÐÛ ððóððóîððë ¬± ððóððóîððë ìò Ì×ÌÔÛ ßÒÜ ÍËÞÌ×ÌÔÛ ë¿ò ÝÑÒÌÎßÝÌ ÒËÓÞÛÎ ÔËÚÌÉßÚÚÛ ÓßÎ×Ì×ÓÛ ÑÐÛÎßÌ×ÑÒÍ ×Ò ÉÑÎÔÜ ÉßÎ ××æ ë¾ò ÙÎßÒÌ ÒËÓÞÛÎ ÌØÑËÙØÌô ÑÎÙßÒ×ÆßÌ×ÑÒ ßÒÜ ÌÛÝØÒÑÔÑÙÇ ë½ò ÐÎÑÙÎßÓ ÛÔÛÓÛÒÌ ÒËÓÞÛÎ