Adoption: 23 March 2018 Public Publication: 29 March 2018 Greco-Adhocrep(2018)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Measures

Court of Justice of the European Union PRESS RELEASE No 47/20 Luxembourg, 8 April 2020 Order of the Court in Case C-791/19 R Press and Information Commission v Poland Poland must immediately suspend the application of the national provisions on the powers of the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court with regard to disciplinary cases concerning judges The pleas of fact and of law put forward by the Commission justify the grant of interim measures In 2017, Poland adopted the new disciplinary regime for judges of the Sąd Najwyższy (Supreme Court, Poland) and the ordinary courts. Specifically, under that legislative reform, a new Chamber, the Izba Dyscyplinarna (the Disciplinary Chamber) was created within the Sąd Najwyższy. The jurisdiction of the Izba Dyscyplinarna thus covers, inter alia, disciplinary cases concerning judges of the Sąd Najwyższy and, on appeal, those concerning judges of the ordinary courts. Taking the view that, by adopting the new disciplinary regime for judges, Poland had failed to fulfil its obligations under EU law,1 on 25 October 2019 the Commission brought an action before the Court of Justice.2 The Commission claims, inter alia,3 that the new disciplinary regime does not guarantee the independence and impartiality of the Izba Dyscyplinarna , composed exclusively of judges selected by the Krajowa Rada Sądownictwa (the National Council of the Judiciary; ‘the KRS’), the fifteen judges who are members of which were elected by the Sejm (the lower chamber of the Polish Parliament). By its judgment of 19 November -

Legal Think Tanks and Governments. Country Report. Poland

“Legal Think Tanks and government – capacity building”: project supported by the International Visegrad Fund www.visegradfund.org Project partners: POLAND HUNGARY Legal Think Tanks and Government CZECH REPUBLIC – Capacity Building Country Report. Poland SLOVAKIA UKRAINE Authors Łukasz BOJARSKI Grzegorz WIADEREK MOLDOVA 1 Authors of the study Łukasz BOJARSKI President and co-founder of INPRIS, lawyer. Co-founder and Chairman of the Board of the Polish Legal Clinics Foundation (FUPP). Expert of Polish and international institutions (including European Commission, OSCE, Council of Europe, academia, private foundations including Stefan Batory Foundation, Open Society Institute). Member of the Editorial Board of the „National Judicial Council. Quarterly” (http://www.krs.pl/pl/kwartalnik-krs). Before: Member of the National Council of the Judiciary of Poland, (2010-2015). Member of the Board of Directors of PILnet – The Global Network for Public Interest Law (2008-2016). Employee of the Helsinki Foundation of Human Rights in the years 1998-2010. Member of the Experts Council of the „Citizen and the Law” (Obywatel i Prawo) program of the Polish- American Freedom Foundation (2005-2013), Member of the Committee on the Efficiency of Justice in the Ministry of Justice. Fields of interest: judiciary, legal services, legal profession, legal education, non- discrimination, human rights. Author of the reform proposals on the access to legal aid and the legal profession. Author of numerous publications on the judiciary, access to justice and interactive innovative methods in legal education, see list of main publications. Contact: lukasz.bojarski at inpris.pl Grzegorz WIADEREK Co-founder of INPRIS and member of the Management Board, lawyer. -

China at the Gates a New Power Audit of Eu-China Relations

CHINA AT THE GATES A NEW POWER AUDIT OF EU-CHINA RELATIONS François Godement & Abigaël Vasselier ABOUT ECFR The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) is the first pan-European think-tank. Launched in October 2007, its objective is to conduct research and promote informed debate across Europe on the development of coherent, effective and values- based European foreign policy. ECFR has developed a strategy with three distinctive elements that define its activities: • A pan-European Council. ECFR has brought together a distinguished Council of over two hundred Members - politicians, decision makers, thinkers and business people from the EU’s member states and candidate countries - which meets once a year as a full body. Through geographical and thematic task forces, members provide ECFR staff with advice and feedback on policy ideas and help with ECFR’s activities within their own countries. The Council is chaired by Carl Bildt, Emma Bonino and Mabel van Oranje. • A physical presence in the main EU member states. ECFR, uniquely among European think-tanks, has offices in Berlin, London, Madrid, Paris, Rome, Sofia and Warsaw. Our offices are platforms for research, debate, advocacy and communications. • Developing contagious ideas that get people talking. ECFR has brought together a team of distinguished researchers and practitioners from all over Europe to carry out innovative research and policy development projects with a pan-European focus. ECFR produces original research; publishes policy reports; hosts private meetings, public debates, and “friends of ECFR” gatherings in EU capitals; and reaches out to strategic media outlets. ECFR is a registered charity funded by the Open Society Foundations and other generous foundations, individuals and corporate entities. -

Relations Between Chambers in Bicameral Parliaments 121

Relations between Chambers in Bicameral Parliaments 121 III. Relations between Chambers in Bicameral Parliaments 1. Introductory Note by the House of Commons of Canada, June 1991 In any bicameral parliament the two Houses share in the making of legisla- tion, and by virtue both of being constituent parts of the same entity and of this shared function have a common bond or link. The strength or weakness of this link is initially forged by the law regulating the composition, powers and functions of each Chamber, but is tempered by the traditions, practices, the prevailing political, social and economic climate and, indeed, even the personalities which comprise the two Chambers. Given all of these variables and all of the possible mutations and combina- tions of bicameral parliaments in general, no single source could presume to deal comprehensively with the whole subject of relations between the Houses in bicameral parliaments. Instead, the aim of the present notes is to attempt to describe some of the prominent features of relations between the two Houses of the Canadian Parliament with a view to providing a focus for discussion. The Canadian Context The Constitution of Canada provided in clear terms: "There shall be One Parliament for Canada, consisting of the Queen, an Upper House styled the Senate, and the House of Commons." The Senate, which was originally designed to protect the various regional, provincial and minority interests in our federal state and to afford a sober second look at legislation, is an appointed body with membership based on equal regional representation. Normally the Senate is composed of 104 seats which are allotted as follows: 24 each in Ontario, Quebec, the western provinces (6 each for Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia) and the Maritimes (10 each in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick and 4 in Prince Edward Island); six in Newfoundland and one each in the Yukon and Northwest Territories. -

Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Gospodarki Krajowej W Kutnie

Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie NR 14 GRUDZIEŃ 2020 PÓŁROCZNIK ISSN 2353-8392 KUTNO 2020 Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie Wydział Studiów Europejskich Rada Programowo-Naukowa Przewodniczący Rady: prof. dr hab. Anatoliy Romanyuk, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie Zastępca Przewodniczącego: dr hab. Zbigniew Białobłocki, Wyższa Szkoła Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie Członkowie: prof. dr hab. Wiera Burdiak, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. Jurija Fedkowycza w Czerniowcach prof. dr hab. Walerij Bebyk, Narodowy Uniwersytet Kijowski im. Tarasa Szewczenki prof. dr hab. Markijan Malski, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie prof. zw. dr hab. Lucjan Ciamaga, Wyższa Szkoła Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie dr hab. Krzysztof Hajder, Uniwersytet im. A. Mickiewicza w Poznaniu prof. dr hab. Walenty Baluk, Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie prof. nadzw. dr Vitaliy Lytvin, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie prof. Pavel Pavlov, PhD, Prorektor ds Badań i Nauki Wolnego Uniwersytetu Warneńskiego prof. Galya Gercheva D.Sc, Rektor Wolnego Uniwersytetu Warneńskiego, ks. dr hab. Kazimierz Pierzchała, Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski Jana Pawła II Recenzenci zewnętrzni: prof. dr hab. Nataliya Antonyuk, Uniwersytet Opolski prof. dr hab. Walerij Denisenko Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie prof. zw. dr hab. Bogdan Koszel, Uniwersytet im. A. Mickiewicza w Poznaniu prof. dr hab. Janusz Soboń, Akademia im. Jakuba z Paradyża w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim prof. dr hab. Wasyl Klimonczuk, Narodowy Uniwersytet Przykarpacki im. Wasyla Stefanyka w Iwano Frankowsku prof. dr hab. Swietłana Naumkina, Narodowy Juznoukrainski Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny im. K. D. Uszynskiego w Odessie prof. dr hab. Galina Zelenjno, Instytut Etnopolitologii im. I. Kurasa w Kijowie dr hab. Krystyna Leszczyńska- Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie Redaktor naczelny: dr hab. -

ACT of 8 December 2017 on the Supreme Court Chapter 1 General

Appendix to the announcement of the Speaker of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland of 4 April 2019 (item 825) regarding the publication of a uniform text of the Supreme Court Act ACT of 8 December 2017 on the Supreme Court Chapter 1 General provisions Article 1. The Supreme Court shall be a judiciary body responsible for: 1) the administration of justice by: a) ensuring the legality and uniformity of the case law of common courts and military courts by examining appeals and passing resolutions resolving legal questions; b) 1extraordinary review of valid court judgments to ensure their consistency with the principle of a democratic state ruled by law implementing the principles of social justice by the examination of extraordinary appeals; 2) examining disciplinary cases to the extent defined by statute; 3) examining election protests and confirming the validity of elections to the Sejm and the Senate, the election of the President of the Republic of Poland, elections to the European Parliament, and examining protests concerning the validity of a national referendum or a constitutional referendum, and confirming the validity of a referendum; 4) issuing opinions on draft statutes and other normative acts under which courts adjudicate and function, as well as other draft statutes to the extent that they affect cases within the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court; 5) performing other actions defined by statute. Article 2. The Supreme Court shall have its seat in Warsaw. Article 3. The Supreme Court shall be divided into Chambers: 1) Civil Chamber; 2) Criminal Chamber; 3) Labour Law and Social Security Chamber; 4) Extraordinary Review and Public Affairs Chamber; 5) Disciplinary Chamber. -

POLAND Date of Elections: March 21, 1976 Purpose of Elections

POLAND Date of Elections: March 21, 1976 Purpose of Elections Elections were held for all the members of Parliament on the normal expiry of their term of office. Characteristics of Parliament The unicameral Parliament of Poland, the Sejm (Diet), is composed of 460 members elected for 4 years. Electoral System All Polish citizens are entitled to vote provided they are at least 18 years old, have not been convicted of crime or deprived of their civil rights by judgement of a court and are not mentally deficient. Also entitled are persons who have resided in Poland for five years and have no other nationality, even if their Polish citizenship is not yet established. Electoral registers are drawn up at the constituency level by the local people's councils and revised before each election. Voting is not compulsory. Any qualified elector who is at least 21 years of age may stand for election to the Diet. The mandate of deputy is not incompatible with any other public or private function. According to the Constitution amended in 1976, candidates are nominated by political and social organizations embracing the country's urban and rural population. For the 1976 general elections, Poland was divided into 71 constituencies, each returning from three to ten deputies, depending on the constituency's population. Deputies are elected by absolute majority system, with electors in each constituency voting for lists of candidates presented by political parties. Each elector votes for as many candidates as there are seats to be filled in the constituency and, since the names on any party list can exceed this total, may cast preferential votes for candidates of his choice by crossing out names of others. -

Eu:C:2019:325 1 Opinion of Mr Tanchev – Case C-619/18 Commission V Poland (Independence of the Supreme Court)

Report s of C ases OPINION OF ADVOCATE GENERAL TANCHEV delivered on 11 April 2019 1 Case C-619/18 European Commission v Republic of Poland (Failure of a Member State to fulfil obligations — Article 258 TFEU — Article 7 TEU — Rule of law — Article 19(1) TEU — Principle of effective judicial protection — Principles of independence and irremovability of judges — Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union — Articles 47 and 51 — National measures lowering the retirement age of Supreme Court judges in office — Absence of a transitional period — National measures granting the President of the Republic discretion to extend the active mandate of Supreme Court judges) I. Introduction 1. In the present case, the Commission has brought infringement proceedings against the Republic of Poland under Article 258 TFEU for failing to fulfil its obligations under the combined provisions of the second subparagraph of Article 19(1) TEU and Article 47 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (‘the Charter’), on the grounds that, first, national measures lowering the ą ż retirement age of the judges of the S d Najwy szy (Supreme Court, Poland) appointed to that court before 3 April 2018 infringe the principle of irremovability of judges, and second, national measures granting the President of the Republic discretion to extend the active mandate of Supreme Court judges upon reaching the lowered retirement age infringe the principle of judicial independence. 2. Fundamentally, this case presents the Court with the opportunity to rule, for the first time within the context of a direct action for infringement under Article 258 TFEU, on the compatibility of certain measures taken by a Member State concerning the organisation of its judicial system with the standards set down in the second subparagraph of Article 19(1) TEU, combined with Article 47 of the 2 Charter, for ensuring respect for the rule of law in the Union legal order. -

Effects of Institutional Variables on Legislative Voting Behaviour: Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Eight Bicameral Legislatures

MASARYK UNIVERSITY The Faculty of Social Studies The Department of Political Science Mgr. Kamil Gregor Effects of Institutional Variables on Legislative Voting Behaviour: Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Eight Bicameral Legislatures Dissertation Thesis Advisor: Prof. PhDr. Maxmilián Strmiska, Ph.D. Brno 2015 1 Affidavit / Čestné prohlášení I declare that this thesis was written by me alone and using only sources listed in References. Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto dizertační práce vypracoval samostatně a pouze s použitím uvedených zdrojů. Brno, 20. 11. 2015 Mgr. Kamil Gregor 2 Abstract This thesis challenges conventional straightforward accounts of legislative voting behaviour found in existing literature by systematically testing a set of hypotheses regarding effects of three institutional independent variables – the dependency of the executive on the legislature, party leadership control over prospects of legislators’ re-election and cameral symmetry – on two dependent variables describing legislative voting behaviour – party group unity and prevalence of strategic legislative voting. In order to control for effects of possible intervening variables, a quasi-experimental design is employed: Values of the three independent variables are dichotomized and eight national bicameral legislatures with all possible combinations of these values are analysed. Differences in values of the dependent variables between the lower and the upper chamber in each legislature are measured. The differences are then used as the outcome in the csQCA method in order to estimate combinations of institutional conditions necessary and sufficient for the measured differences to occur. The thesis finds that in symmetrical legislatures, strategic legislative voting is similarly prevalent in both chambers while in asymmetrical legislatures, it is more prevalent in the lower chamber. -

The Right to Claim Innocence in Poland

This article from Erasmus Law Review is published by Eleven international publishing and made available to anonieme bezoeker The Right to Claim Innocence in Poland Wojciech Jasiński & Karolina Kremens* Abstract ment, leaving it on the fringes of interest for Polish aca- demics. Only occasionally do miscarriages of justice, Wrongful convictions and miscarriages of justice, their their reasons and effects, attract academic debate.1 The reasons and effects, only rarely become the subject of aca- issue of the compensation for wrongful conviction demic debate in Poland. This article aims at filling this gap attracts more attention.2 However, the studies rarely and providing a discussion on the current challenges of involve analysis of quantitative and qualitative data con- mechanisms available in Polish law focused on the verifica- cerning wrongful convictions and their reasons.3 Alto- tion of final judgments based on innocence claims. While gether, the research relating to this issue is not even there are two procedures designed to move such judgment: comparable to that carried out on that topic, especially cassation and the reopening of criminal proceedings, only in the US, but also in Europe.4 This seems intriguing. the latter aims at the verification of new facts and evidence, Miscarriages of justice affect their victims in various and this work remains focused exactly on that issue. The ways. They range from physical and psychological to article begins with a case study of the famous Komenda social and financial harm of the persons directly or indi- case, which resulted in a successful innocence claim, serving rectly affected by wrongful conviction.5 But they also as a good, though rare, example of reopening a case and impact the whole society since convicting the innocent acquitting the convict immediately and allows for discussing means that criminal justice system failed to protect the the reasons that commonly stand behind wrongful convic- victims of crime. -

Member States May Not Impose Mandatory Liquidation on Companies That Wish to Transfer Their Registered Office to Another Member State

Court of Justice of the European Union PRESS RELEASE No 112/17 Luxembourg, 25 October 2017 Judgment in Case C-106/16 Press and Information Polbud – Wykonawstwo sp. z o.o. Member States may not impose mandatory liquidation on companies that wish to transfer their registered office to another Member State The transfer of the registered office of such a company, when there is no change in the location of its real head office, falls within the scope of the freedom of establishment protected by EU law Polbud is a company established in Poland. By a resolution in 2011, an extraordinary general meeting of shareholders of that company decided to transfer the company’s registered office to Luxembourg. That resolution makes no reference to a transfer to Luxembourg of either the place where Polbud’s business is managed or of the place where that company’s business is actually carried out. On the basis of that resolution, the opening of a liquidation procedure was recorded in the Polish commercial register and a liquidator was appointed. In 2013 the registered office of Polbud was transferred to Luxembourg. Polbud then became ‘Consoil Geotechnik Sàrl’, a company under Luxembourg law. Further, Polbud lodged an application at the Polish registry court for its removal from the Polish commercial register. The registry court refused the application for removal. Polbud brought an action against that decision. The Sąd Najwyższy (Supreme Court of Poland), before which an appeal has brought, first asks the Court of Justice whether freedom of establishment is applicable to the transfer of only the registered office of a company incorporated under the law of one Member State to the territory of another Member State, where that company is converted to a company under the law of that other Member State, when there is no change of location of the real head office of that company. -

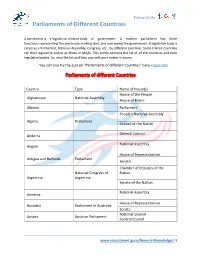

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly