Satellite Radio Monopoly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complaint : U.S. Et Al., V. Echostar Communications Corp. Et Al

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) United States Department of Justice ) Antitrust Division ) 1401 H Street, N.W., Suite 8000 ) Washington, DC 20530, ) ) CASE NUMBER 1:02CV02138 STATE OF MISSOURI ) Missouri Attorney General’s Office ) JUDGE: Ellen Segal Huvelle P.O. Box 899 ) Jefferson City, MO 65102, ) DECK TYPE: Antitrust ) STATE OF ARKANSAS ) DATE STAMP: 10/31/2002 Office of the Attorney General ) Antitrust Division ) 323 Center Street, Suite 200 ) Little Rock, Arkansas 72201, ) ) STATE OF CALIFORNIA ) California Department of Justice ) Ronald Reagan Building ) 300 S. Spring St., Suite 5N ) Los Angeles, CA 90013, ) ) STATE OF CONNECTICUT ) Office of the Attorney General ) 110 Sherman Street ) Hartford, CT 06105, ) ) STATE OF HAWAII ) Department of the Attorney General ) 425 Queen Street ) Honolulu, Hawaii 96813, ) ) STATE OF IDAHO ) Office of Attorney General ) P.O. Box 83720 ) Boise, Idaho 83720-0010, ) ) STATE OF ILLINOIS ) Office of the Attorney General ) James R. Thompson Center ) 100 W. Randolph Street, 13th Floor ) Chicago, IL 60601, ) ) STATE OF IOWA ) Department of Justice ) Hoover Office Building, 2nd Floor ) Des Moines, IA 50319, ) ) COMMONWEALTH OF KENTUCKY ) 1024 Capital Center Drive ) Frankfort, KY 40601, ) ) STATE OF MAINE ) Office of the Attorney General ) 6 State House Station ) Augusta, Maine 04333, ) ) COMMONWEALTH OF ) MASSACHUSETTS ) Office of the Attorney General ) One Ashburton Place, 19th Floor ) Boston, MA 02108, ) ) STATE OF MISSISSIPPI ) P.O. Box 22947 ) Jackson, MI 39225, ) ) STATE OF MONTANA ) P.O. Box 200501 ) Helena, MT 59620-0501, ) ) STATE OF NEVADA ) Office of the Attorney General ) 1000 East William Street ) Suite 200 ) Carson City, Nevada 89701, ) ) STATE OF NEW YORK ) Office of the Attorney General ) 120 Broadway, 26C ) New York, New York 10271, ) ) STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA ) Department of Justice ) P.O. -

Echostar Annual Report Year Ended December 31, 2012 March 20, 2013

NASDAQ: SATS 100 Inverness Terrace East Englewood, CO 80112 303.706.4000 | echostar.com EchoStar Annual Report Year Ended December 31, 2012 March 20, 2013 Dear EchoStar Corporation Shareholders; 2012 was a very busy year for EchoStar. One of the most exciting accomplishments for 2012 was the addition of two new satellites to our growing fleet through the successful launches of EchoStar XVI and EchoStar XVII, bringing our total number of owned, leased and managed spacecraft to twenty-two. EchoStar operates the world’s fourth largest commercial geostationary satellite fleet and we continue to solidify our position as a premier global leader in satellite communications and operations. EchoStar ended 2012 with revenue of $3.1 billion, a growth of 13% over 2011. EBITDA in 2012 was $794 million, a growth of 64% over 2011. We generated a healthy $508 million of cash from operating activities in 2012 as a result primarily of the strong net income in 2012 and ended the year with a strong balance sheet with $1.5 billion of cash and marketable securities. EchoStar reached two very important long-term North America goals in 2012 with the market implementation of the HughesNet Gen4 service and the roll-out of the Hopper Whole Home DVR solution for DISH. Both solutions are garnering high praise and rapid adoption by consumers, a glowing testament to the capabilities and ingenuity of the EchoStar team. Additional notable accomplishments for 2012 include the very successful introduction of two new Slingbox retail products, several large enterprise contract renewals and new customers for Hughes data network services around the globe, and above-forecast sales of set-top-box products and video services to our established operator customers. -

Satellite Industry Association Comments in Docket No

June 7, 2021 Via E-Mail Attn: Diane Steinour National Telecommunications and Information Administration 1401 Constitution Ave NW Room 4701 Washington, DC 20230 Re: Satellite Industry Association Comments in Docket No. 210503–0097 Dear Ms. Steinour, The Satellite Industry Association (SIA)1 hereby provides its comments in the Telecommunications/ICT Development Activities, Priorities and Policies To Connect the Unconnected Worldwide in Light of the 2021 International Telecommunication Union (ITU) World Telecommunication Development Conference (WTDC–21) proceeding referenced above (hereinafter, RFC).2 SIA is a U.S.- based trade association representing the leading satellite operators, manufacturers, launch providers, and ground equipment suppliers who serve commercial, civil, and military markets. The satellite industry has a long history of supporting ICT development activities and providing connectivity to unserved and underserved communities worldwide, and fully supports the efforts of the Administration, the Department of Commerce (DOC) and the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) in this area. 1. ICT Development Priorities a. Over the next five years, what should the U.S. government priorities be for telecommunications/ICT development? b. Are there particular areas of focus for economic development, as well as telecommunications/ICT development that might help the United States align with developing countries’ development interests? c. What are valuable venues, forums, or methods to focus this work? 1 SIA -

Echostar Corporation (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-Q (Mark One) þ QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE QUARTERLY PERIOD ENDED MARCH 31, 2008. OR o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO . Commission File Number: 001-33807 EchoStar Corporation (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Nevada 26-1232727 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 90 Inverness Circle E. Englewood, Colorado 80112 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) (303) 706-4000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Not Applicable (Former name, former address and former fiscal year, if changed since last report) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes þ No o Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, or a smaller reporting company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer” and “smaller reporting company” in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act. (Check one): Large accelerated filer o Accelerated filer o Non-accelerated filer þ Smaller reporting company o (Do not check if a smaller reporting company) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). -

PUBLIC NOTICE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION 445 12Th STREET S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION 445 12th STREET S.W. WASHINGTON D.C. 20554 News media information 202-418-0500 Fax-On-Demand 202-418-2830; Internet: http://www.fcc.gov (or ftp.fcc.gov) TTY (202) 418-2555 DA No. 07-120 Report No. SAT-00413 Friday January 19, 2007 POLICY BRANCH INFORMATION Actions Taken The Commission, by its International Bureau, took the following actions pursuant to delegated authority. The effective date of these actions is the release date of this Notice, except were an effective date is specified. SAT-LOA-20061222-00157 E S2716 EchoStar Satellite Operating Corporation Launch and Operating Authority Withdrawn Effective Date: 01/05/2007 Nature of Service: Direct to Home Fixed Satellite, Fixed Satellite Service SAT-LOA-20061222-00158 E S2717 EchoStar Satellite Operating Corporation Launch and Operating Authority Withdrawn Effective Date: 01/05/2007 Nature of Service: Direct to Home Fixed Satellite, Fixed Satellite Service SAT-LOA-20061222-00159 E S2718 EchoStar Satellite Operating Corporation Launch and Operating Authority Withdrawn Effective Date: 01/05/2007 Nature of Service: Direct to Home Fixed Satellite, Fixed Satellite Service SAT-LOA-20061222-00160 E S2719 EchoStar Satellite Operating Corporation Launch and Operating Authority Withdrawn Effective Date: 01/05/2007 Nature of Service: Direct to Home Fixed Satellite, Fixed Satellite Service SAT-LOA-20061222-00161 E S2720 EchoStar Satellite Operating Corporation Launch and Operating Authority Withdrawn Effective Date: 01/05/2007 Page 1 of 3 Nature of Service: Direct to Home Fixed Satellite, Fixed Satellite Service SAT-LOA-20061222-00162 E S2721 EchoStar Satellite Operating Corporation Launch and Operating Authority Withdrawn Effective Date: 01/05/2007 Nature of Service: Direct to Home Fixed Satellite, Fixed Satellite Service SAT-LOA-20061222-00163 E S2722 EchoStar Satellite Operating Corporation Launch and Operating Authority Withdrawn Effective Date: 01/05/2007 Nature of Service: Direct to Home Fixed Satellite, Fixed Satellite Service SAT-STA-20050601-00113 E XM Radio Inc. -

The Mistake of Conditioning Approval of the Sirius-XM Merger on a Price Cap, 3 Brook

Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law Volume 3 | Issue 2 Article 8 2009 Are You Sirius? The iM stake of Conditioning Approval of the Sirius-XM Merger on a Price Cap Samuel J. Gordon Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl Recommended Citation Samuel J. Gordon, Are You Sirius? The Mistake of Conditioning Approval of the Sirius-XM Merger on a Price Cap, 3 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. (2009). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl/vol3/iss2/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. ARE YOU SIRIUS? THE MISTAKE OF CONDITIONING APPROVAL OF THE SIRIUS-XM MERGER ON A PRICE CAP On July 25, 2008, in a 3–2 decision along party lines, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC or Commission) voted to give the government’s final stamp of approval on the merger of Sirius Satellite Radio Inc. (Sirius) and XM Satellite Radio Holdings Inc. (XM) (collectively, the Applicants).1 The $3.3 billion dollar merger “was one of the most protracted in U.S. history,”2 not receiving approval until seventeen months after it was first proposed.3 The merger combined “the only entities authorized by the Commission to provide satellite radio service in the United States,”4 leaving just one satellite radio company, the newly merged Sirius XM Radio Inc.,5 to control the satellite radio frequencies and provide -

SES SES GLOBAL AMERICAS HOLDINGS GP Château De Betzdorf 4 Research Way L-6815 Betzdorf Princeton Luxembourg New Jersey 08540 United States of America

PROSPECTUS SES (incorporated as a société anonyme under the laws of Luxembourg ) SES GLOBAL AMERICAS HOLDINGS GP (established as a general partnership under the laws of the State of Delaware ) €4,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme This document comprises two base prospectuses (together, the Prospectus ): (i) the base prospectus for SES in respect of non-equity securities within the meaning of Article 22 no. 6(4) of Commission Regulation (EC) No. 809/2004 of 29 April 2004 implementing Directive 2003/71/EC of 4 November 2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the prospectus to be published when securities are offered to the public or admitted to trading and amending Directive 2001/34/EC, as amended (the Notes ) to be issued by it under this €4,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the Programme ) and (ii) the base prospectus for SES Global Americas Holdings GP ( SES Americas ) in respect of Notes to be issued by it under this Programme. Under the Programme, SES and SES Americas (each an Issuer and, together, the Issuers ) may from time to time issue Notes denominated in any currency agreed between the relevant Issuer and the relevant Dealer (as defined below). The payment of all amounts due in respect of the Notes issued by SES Americas will be unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by SES and the payment of all amounts due in respect of the Notes issued by SES will, subject to the provisions of Condition 17 in “ Terms and Conditions of the Notes ”, be unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by SES Americas (each in its capacity as guarantor, the Guarantor ). -

2020 Annual Report

20ANNUAL 20REPORT YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 CONNECTING THE WORLD March 17, 2021 Dear EchoStar Corporation Shareholder, 2020 was a challenging year for everyone, but despite all the hurdles, our EchoStar team delivered. When it was needed the most, our team rose to the occasion and delivered essential broadband services and technologies connecting millions around the world while continuing to innovate and move the business forward. Notable highlights of 2020 include: • More than 1.5 million subscribers across two continents rely on HughesNet® for their internet access, including approximately 375,000 subscribers across Latin America. • The Gartner November 2020 Magic Quadrant for Managed Network Services recognized the Hughes Division as a pioneer of performance optimization technology. The Frost & Sullivan 2020 Frost Radar report rated Hughes as a leader in both growth and innovation, ranking among the top three managed SD-WAN providers for growth • We joined the consortium purchasing OneWeb out of bankruptcy and were selected to develop and manufacture essential ground system technology for the new LEO constellation. • We partnered with Jersey Telecom to bring true, hybrid satellite/cellular capability to Internet of Things (IoT) and Mobility customers across Europe and the U.K. • The Government Innovation Awards named Hughes an Industry Innovator, for its work at the forefront of government network modernization. • Inmarsat chose to partner with Hughes for its new GX North America aero service, leveraging the capacity density of -

Thales and SES Select Hughes for Next-Generation Aviation Connectivity Network to Provide Increased Capacity, Coverage and Redundancy Over the Americas

March 8, 2017 Thales and SES Select Hughes for Next-Generation Aviation Connectivity Network to Provide Increased Capacity, Coverage and Redundancy over the Americas ARLINGTON, Va. and LUXEMBOURG and GERMANTOWN, Md., March 8, 2017 /PRNewswire/ -- SES contracts Hughes for service on EchoStar XVII and EchoStar XIX HTS satellites, and combines them with its AMC- 15 and AMC-16 network, to provide a four-satellite constellation for the launch of Thales FlytLIVE network The four-satellite network strengthens Thales' FlytLIVE network as it enters initial operations in 2017 and in advance of the milestone launch of SES-17 Ka-band HTS satellite, planned for 2020 SES to purchase multiple JUPITER System gateways from Hughes and contract ground segment operations to Hughes to bring seamless connectivity to Thales FlytLIVE network Thales selects Hughes JUPITER System Aeronautical platform for its next-generation IFC solution Today, Thales, SES S.A. and Hughes Network Systems (HUGHES) announced a set of strategic agreements to enhance the delivery of FlytLIVE™ - Thales' connected inflight experience solution, offering the most advanced and efficient aeronautical connectivity solution available in the Americas. Under the agreements, SES contracts capacity on Hughes EchoStar XVII and EchoStar XIX high throughput (HTS) Ka-band satellites to complement its AMC-15 and AMC-16 network giving FlytLIVE the only redundant coverage network in North America. SES will also purchase multiple JUPITER™ System gateways from Hughes to qualify Thales to deploy its FlytLIVE service on Hughes JUPITER Aeronautical platform. This will allow Thales to initiate its next-generation connected inflight experience offering in North America this year. -

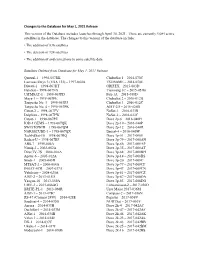

Changes to the Database for May 1, 2021 Release This Version of the Database Includes Launches Through April 30, 2021

Changes to the Database for May 1, 2021 Release This version of the Database includes launches through April 30, 2021. There are currently 4,084 active satellites in the database. The changes to this version of the database include: • The addition of 836 satellites • The deletion of 124 satellites • The addition of and corrections to some satellite data Satellites Deleted from Database for May 1, 2021 Release Quetzal-1 – 1998-057RK ChubuSat 1 – 2014-070C Lacrosse/Onyx 3 (USA 133) – 1997-064A TSUBAME – 2014-070E Diwata-1 – 1998-067HT GRIFEX – 2015-003D HaloSat – 1998-067NX Tianwang 1C – 2015-051B UiTMSAT-1 – 1998-067PD Fox-1A – 2015-058D Maya-1 -- 1998-067PE ChubuSat 2 – 2016-012B Tanyusha No. 3 – 1998-067PJ ChubuSat 3 – 2016-012C Tanyusha No. 4 – 1998-067PK AIST-2D – 2016-026B Catsat-2 -- 1998-067PV ÑuSat-1 – 2016-033B Delphini – 1998-067PW ÑuSat-2 – 2016-033C Catsat-1 – 1998-067PZ Dove 2p-6 – 2016-040H IOD-1 GEMS – 1998-067QK Dove 2p-10 – 2016-040P SWIATOWID – 1998-067QM Dove 2p-12 – 2016-040R NARSSCUBE-1 – 1998-067QX Beesat-4 – 2016-040W TechEdSat-10 – 1998-067RQ Dove 3p-51 – 2017-008E Radsat-U – 1998-067RF Dove 3p-79 – 2017-008AN ABS-7 – 1999-046A Dove 3p-86 – 2017-008AP Nimiq-2 – 2002-062A Dove 3p-35 – 2017-008AT DirecTV-7S – 2004-016A Dove 3p-68 – 2017-008BH Apstar-6 – 2005-012A Dove 3p-14 – 2017-008BS Sinah-1 – 2005-043D Dove 3p-20 – 2017-008C MTSAT-2 – 2006-004A Dove 3p-77 – 2017-008CF INSAT-4CR – 2007-037A Dove 3p-47 – 2017-008CN Yubileiny – 2008-025A Dove 3p-81 – 2017-008CZ AIST-2 – 2013-015D Dove 3p-87 – 2017-008DA Yaogan-18 -

Echostar Annual Report Year Ended December 31, 2011 CORPORATE PROFILE

NASDAQ: SATS 100 Inverness Terrace East Englewood, CO 80112 303.706.4000 www.echostar.com EchoStar Annual Report Year Ended December 31, 2011 CORPORATE PROFILE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ANNUAL MEETING EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Charles W. Ergen The 2012 Annual Meeting of Charles W. Ergen Chairman of the Board Shareholders will be held on Chairman May 3, 2012. Michael T. Dugan Michael T. Dugan Chief Executive Officer Director For additional information, and President contact: R. Stanton Dodge Investor Relations Department Kenneth G. Carroll Director Executive Vice President and EchoStar Corporation Chief Financial Officer Anthony M. Federico 100 Inverness Terrace East Englewood, Colorado 80112 Director Mark W. Jackson www.echostar.com President, Pradman P. Kaul EchoStar Technologies L.L.C. Director Anders N. Johnson President, David K. Moskowitz EchoStar Satellite Services L.L.C. Director Pradman P. Kaul Tom A. Ortolf President, Hughes Communications, Inc. Director Sandra L. Kerentoff C. Michael Schroeder Executive Vice President, Director Global Human Resources Roger J. Lynch TRANSFER AGENT Executive Vice President, Computershare Advanced Technologies L.L.C. Trust Company Dean A. Manson PO Box 43070 Executive Vice President, Providence, RI 02940-3070 General Counsel and Secretary INDENTURE TRUSTEE Steven B. Schaver President, Wells Fargo Bank, EchoStar International Corporation National Association Corporate Trust Services 625 Marquette Ave., 11th Floor MAC N9311-110 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55470 Attn: Richard H. Prokosch March 23, 2012 Dear EchoStar Corporation Shareholders: 2011 will be remembered as a significant growth year for EchoStar Corporation with the acquisition of Hughes Communications, Inc. on June 8, 2011. Hughes is a leading provider of satellite broadband solutions and services for home and office, complementing EchoStar as a premier provider of satellite operations and digital TV solutions that enhance today’s home entertainment lifestyle. -

The FCC's New Formula for Mergers

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 29 Number 3 The Grammy Foundation Entertainment Law Initiative 2009 Writing Article 7 Competition 6-1-2009 The FCC's New Formula for Mergers Bradley Dugan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bradley Dugan, The FCC's New Formula for Mergers, 29 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 435 (2009). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol29/iss3/7 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FCC'S NEW FORMULA FOR MERGERS I. INTRODUCTION Radio consumers may find it absurd to pay for any type of radio programming given that all AM and FM radio broadcasters offer their transmissions for free. Two companies tested the accuracy of this assumption in 1997 by purchasing the available satellite digital audio radio services (SDARS or DARS) spectrum' to create satellite radio--a subscription-based service in which customers receive a broad array of radio programming in exchange for a monthly fee. 2 Nevertheless, a decade after XM Satellite Radio (XM) and Sirius Satellite Radio (Sirius) licensed the SDARS spectrum, the assumption that consumers do not want to pay for radio appeared to be at least partially correct,3 as both companies failed to turn a profit and have almost three billion dollars of debt.4 Due to the high costs of launching satellites and maintaining other infrastructure, as well as the immense expenses of contracting with high-profile on-air personalities, both firms struggled financially.