Enviro-Toons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imaginationland," Terrorism, and the Difference Between Real And

Christopher C. Kirby, PhD. Eastern Washington University Cheney, WA. 99004 “IMAGINATIONLAND,” TERRORISM, AND THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN REAL AND IMAGINARY CHRISTOPHER C. KIRBY Eastern Washington University “Ladies and gentlemen, I have dire news. Yesterday, at approximately 18:00 hours, terrorists successfully attacked... our imagination”1 “Imaginationland” was an Emmy winning, three-part story which aired as the tenth, eleventh and twelfth episodes of South Park’s eleventh season and was later re-issued as a movie with all of the deleted scenes included. The story begins with the boys waiting in the woods for a leprechaun that Cartman claims to have seen. Kyle, ever the skeptic, has bet ten dollars against sucking Cartman’s balls that leprechauns aren’t real. When the boys finally trap one, to Kyle’s shock and dismay, it cryptically warns of a terrorist attack and disappears. That night at the dinner table Kyle asks his parents where leprechauns come from and why one would visit South Park to warn of a terrorist attack. They chide him for not knowing the difference between real and imaginary and he mutters, “I thought I did.” What ensues is pure South Park genius as we discover that, in fact, nobody seems to know what the difference is. As the story unfolds it’s obvious that no one will be safe, as the episode lampoons the U.S. “war on terror,” the American legal system, Hollywood directors, the media, Christianity, the military, Kurt Russell, and Al Gore’s campaign against climate change [ManBearPig is real… I’m super cereal!] all the while reminding us that imagination is an essential feature of human life. -

View/Method……………………………………………………9

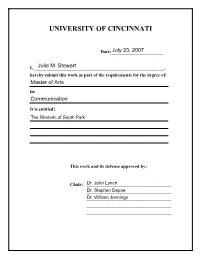

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Ohio State University Alexandra Mary Jenkins, M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Jared Gardner, Advisor Sean O’Sullivan Robyn Warhol Copyright by Alexandra Mary Jenkins 2014 Abstract Feminist activism in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s harnessed radical social thought and used innovative expressive forms in order to disrupt the “grand perspective” espoused by men in every field (Adorno 206). Feminist student activists often put their own female bodies on display to disrupt the disembodied “objective” thinking that still seemed to dominate the academy. The philosopher Theodor Adorno responded to one such action, the “bared breasts incident,” carried out by his radical students in Germany in 1969, in an essay, “Marginalia to Theory and Praxis.” In that essay, he defends himself against the students’ claim that he proved his lack of relevance to contemporary students when he failed to respond to the spectacle of their liberated bodies. He acknowledged that the protest movements seemed to offer thoughtful people a way “out of their self-isolation,” but ultimately, to replace philosophy with bodily spectacle would mean to miss the “infinitely progressive aspect of the separation of theory and praxis” (259, 266). Lisa Yun Lee argues that this separation continues to animate contemporary feminist debates, and that it is worth returning to Adorno’s reasoning, if we wish to understand women’s particular modes of theoretical ii insight in conversation with “grand perspectives” on cultural theory in the twenty-first century. -

Liberalism, Neoliberalism, and the Literary Left

Draft of September 7, 2016 Liberalism, Neoliberalism, and the Literary Left Deirdre Nansen McCloskey An interview by W. Stockton and D. Gilson, eds., "Neoliberalism in Literary and Cultural Studies." Forthcoming as a special issue of either Public Cultures or Cultural Critique D.N.Mc: I am always glad to respond to queries from my friends on the left. I was myself once a Joan-Baez socialist, so I know how it feels, and honor the impulse. I’ve noticed that the right tends to think of folks on the left as merely misled, and therefore improvable by instruction—if they will but listen. The left, on the other hand, thinks of folks on the right as non-folk, as evil, as “pro-business,” as against the poor. Therefore the left is not ready to listen to the instruction so helpfully proffered by the right. Why listen to Hitler? For instance, no one among students of literature who considers herself deeply interested in the economy, and left-leaning since she was 16, bothers to read with the serious and open-minded attention she gives to a Harvey or Wallerstein or Jameson anything by Friedman or Mill or Smith. (Foucault, incidentally, was an interesting exception.) Please, dears. I’ve also noticed that the left assumes that it is dead easy to refute the so-called neoliberals. Yet the left does not actually understand most of the arguments the neoliberals make. I don’t mean it disagrees with the arguments. I mean it doesn’t understand them. Not at all. It’s easy to show. -

The True Cost of American Food – Conference Proceedings

i The True Cost of American Food – Conference proceedings Foreword Patrick Holden Founder and Chief Executive of the Sustainable Food Trust I am delighted to be writing this foreword for the proceedings of our conference. I hope it will be a useful resource for everyone with an interest in food systems externalities and True Cost Accounting; and that should include everyone who eats! The True Cost of American Food Conference brought together more than 600 participants to listen to high quality presentations from a wide range of leading experts, representing farming, food businesses, research and academic organizations, policy makers, NGOs, public health institutions, organizations representing civil society and food justice, the investment community, funding foundations and philanthropists. As an organization which has contributed in a significant way to the development of the conceptual framework for True Cost Accounting in food and farming, we were delighted that the conference attracted such an impressive attendance of leaders from a range of sectors, all actively committed to taking this initiative forward. Looking forward, clearly one of the key challenges is how we can best convey an easy-to- grasp understanding of True Cost Accounting to individual citizens, who have reasonably assumed until now that the price tag on individual food products reflects of the true costs involved in its production. As we have now come to realize, this is often far from the case; in fact it would be no exaggeration to state that the current food pricing system is dishonest, in that it fails to include the hidden impacts of the production system, both negative and positive, on the environment and public health. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Die Flexible Welt Der Simpsons

BACHELORARBEIT Herr Benjamin Lehmann Die flexible Welt der Simpsons 2012 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die flexible Welt der Simpsons Autor: Herr Benjamin Lehmann Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen Seminargruppe: FF08w2-B Erstprüfer: Professor Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Christian Maintz (M.A.) Einreichung: Mittweida, 06.01.2012 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The flexible world of the Simpsons author: Mr. Benjamin Lehmann course of studies: Film und Fernsehen seminar group: FF08w2-B first examiner: Professor Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Christian Maintz (M.A.) submission: Mittweida, 6th January 2012 Bibliografische Angaben Lehmann, Benjamin: Die flexible Welt der Simpsons The flexible world of the Simpsons 103 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2012 Abstract Die Simpsons sorgen seit mehr als 20 Jahren für subversive Unterhaltung im Zeichentrickformat. Die Serie verbindet realistische Themen mit dem abnormen Witz von Cartoons. Diese Flexibilität ist ein bestimmendes Element in Springfield und erstreckt sich über verschiedene Bereiche der Serie. Die flexible Welt der Simpsons wird in dieser Arbeit unter Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen auf den Wiedersehenswert der Serie untersucht. 5 Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ............................................................................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis .................................................................................... 7 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................... -

Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die

H O S n o t p U e c n e d u r P Saturday, October 7, 201 7, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Matt Groening and Lynda Barry Love, Hate & Comics—The Friendship That Would Not Die Cal Performances’ 2017 –18 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. ABOUT THE ARTISTS Matt Groening , creator and executive producer Simpsons , Futurama, and Life in Hell . Groening of the Emmy Award-winning series The Simp - has launched The Simpsons Store app and the sons , made television history by bringing Futuramaworld app; both feature online comics animation back to prime time and creating an and books. immortal nuclear family. The Simpsons is now The multitude of awards bestowed on Matt the longest-running scripted series in television Groening’s creations include Emmys, Annies, history and was voted “Best Show of the 20th the prestigious Peabody Award, and the Rueben Century” by Time Magazine. Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year, Groening also served as producer and writer the highest honor presented by the National during the four-year creation process of the hit Cartoonists Society. feature film The Simpsons Movie , released in Netflix has announced Groening’s new series, 2007. In 2009 a series of Simpsons US postage Disenchantment . stamps personally designed by Groening was released nationwide. Currently, the television se - Lynda Barry has worked as a painter, cartoon - ries is celebrating its 30th anniversary and is in ist, writer, illustrator, playwright, editor, com - production on the 30th season, where Groening mentator, and teacher, and found they are very continues to serve as executive producer. -

Kulturní Stereotypy V Seriálu Futurama Petr Bílek

Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci Katedra žurnalistiky KULTURNÍ STEREOTYPY V SERIÁLU FUTURAMA Magisterská diplomová práce Petr Bílek Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Lukáš Záme čník, Ph.D. Olomouc 2013 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem p řiloženou práci „Kulturní stereotypy v seriálu Futurama“ vypracoval samostatn ě a použité zdroje jsem uvedl v seznamu pramen ů a literatury. Celkový po čet znak ů práce (bez poznámek pod čarou a seznam ů zdroj ů) činí 148 005. V Olomouci dne ........... Podpis: 2 Pod ěkování Rád bych pod ěkoval Mgr. Lukáši Záme čníkovi, Ph.D., za vedení mé práce. Mé díky pat ří také Mgr. Monice Bartošové a Mgr. Šárce Novotné za jejich inspirativní p řipomínky a Zuzan ě Kohoutové za neúnavný dohled nad jazykovou stránkou práce. 3 Anotace Kulturní stereotypy jsou b ěžnou sou částí mezilidské komunikace a pomáhají lidem v orientaci ve sv ětě. Zárove ň v sob ě skrývají spole čenské hodnoty a mohou být nástrojem moci. Má práce zkoumá jejich užití v amerických animovaných seriálech Futurama a Ugly Americans. V práci jsem užil metodu zakotvené teorie. Pomocí jejích postup ů jsem vytvo řil osm tematických kategorií užitých stereotyp ů. Ty jsem pak mezi ob ěma seriály komparoval. Krom ě samotného obsahu stereotypního zobrazování má práce zkoumala jednotlivé strategie jejich užití. Klí čová slova: kulturní stereotyp, animovaný seriál, Futurama, Ugly Americans 4 Summary Cultural stereotypes are a common part of interpersonal communication, they help people to understand the world. They also include the social value and they can be an instrument of power. My theses investigates their using in American animated series Futurama and Ugly Americans. -

I Huvudet På Bender Futurama, Parodi, Satir Och Konsten Att Se På Tv

Lunds universitet Oscar Jansson Avd. för litteraturvetenskap, SOL-centrum LIVR07 Handledare: Paul Tenngart 2012-05-30 I huvudet på Bender Futurama, parodi, satir och konsten att se på tv Innehållsförteckning Förord ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Inledning ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Tidigare forskning och utmärkelser ................................................................................... 7 Bender’s Head, urval och disposition ................................................................................ 9 Teoretiska ramverk och utgångspunkter .................................................................................. 11 Förförståelser, genre och tolkning .................................................................................... 12 Parodi, intertextualitet och implicita agenter ................................................................... 18 Parodi och satir i Futurama ...................................................................................................... 23 Ett inoriginellt medium? ................................................................................................... 26 Animerad sitcom vs. parodi ............................................................................................. 31 ”Try this, kids at home!”: parodins sammanblandade världar ........................................ -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised.