Women's Experimental Autobiography from Counterculture Comics to Transmedia Storytelling: Staging Encounters Across Time, Space, and Medium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

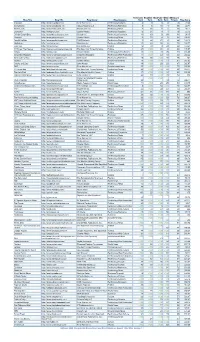

Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Technorati Rank

Technorati Bloglines BlogPulse Wikio SEOmoz’s Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Rank Rank Rank Rank Trifecta Blog Score Engadget http://www.engadget.com Time Warner Inc. Technology/Gadgets 4 3 6 2 78 19.23 Boing Boing http://www.boingboing.net Happy Mutants LLC Technology/Marketing 5 6 15 4 89 33.71 TechCrunch http://www.techcrunch.com TechCrunch Inc. Technology/News 2 27 2 1 76 42.11 Lifehacker http://lifehacker.com Gawker Media Technology/Gadgets 6 21 9 7 78 55.13 Official Google Blog http://googleblog.blogspot.com Google Inc. Technology/Corporate 14 10 3 38 94 69.15 Gizmodo http://www.gizmodo.com/ Gawker Media Technology/News 3 79 4 3 65 136.92 ReadWriteWeb http://www.readwriteweb.com RWW Network Technology/Marketing 9 56 21 5 64 142.19 Mashable http://mashable.com Mashable Inc. Technology/Marketing 10 65 36 6 73 160.27 Daily Kos http://dailykos.com/ Kos Media, LLC Politics 12 59 8 24 63 163.49 NYTimes: The Caucus http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com The New York Times Company Politics 27 >100 31 8 93 179.57 Kotaku http://kotaku.com Gawker Media Technology/Video Games 19 >100 19 28 77 216.88 Smashing Magazine http://www.smashingmagazine.com Smashing Magazine Technology/Web Production 11 >100 40 18 60 283.33 Seth Godin's Blog http://sethgodin.typepad.com Seth Godin Technology/Marketing 15 68 >100 29 75 284 Gawker http://www.gawker.com/ Gawker Media Entertainment News 16 >100 >100 15 81 287.65 Crooks and Liars http://www.crooksandliars.com John Amato Politics 49 >100 33 22 67 305.97 TMZ http://www.tmz.com Time Warner Inc. -

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014

Books Added to the Collection: July 2014 - August 2016 *To search for items, please press Ctrl + F and enter the title in the search box at the top right hand corner or at the bottom of the screen. LEGEND : BK - Book; AL - Adult Library; YPL - Children Library; AV - Audiobooks; FIC - Fiction; ANF - Adult Non-Fiction; Bio - Biography/Autobiography; ER - Early Reader; CFIC - Picture Books; CC - Chapter Books; TOD - Toddlers; COO - Cookbook; JFIC - Junior Fiction; JNF - Junior Non Fiction; POE -Children's Poetry; TRA - Travel Guide Type Location Collection Call No Title AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GIL Big magic : Creative living / Elizabeth Gilbert. AV AL ANF CD 153.3 GRA Originals : How non-conformists move the world / Adam Grant. Irrationally yours : On missing socks, pick up lines, and other existential puzzles / Dan AV AL ANF CD 153.4 ARI Ariely. Think like a freak : The authors of Freakonomics offer to retrain your brain /Steven D. AV AL ANF CD 153.43 LEV Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner. AV AL ANF CD 153.8 DWE Mindset : The new psychology of success / Carol S. Dweck. The geography of genius : A search for the world's most creative places, from Ancient AV AL ANF CD 153.98 WEI Athens to Silicon Valley / Eric Weiner. AV AL ANF CD 158 BRO Rising strong / Brene Brown. AV AL ANF CD 158 DUH Smarter faster better : The secrets of prodctivity in life and business / Charles Duhigg. AV AL ANF CD 158.1 URY Getting to yes with yourself and other worthy opponents / William Ury. 10% happier : How I tamed the voice in my head, reduced stress without losing my edge, AV AL ANF CD 158.12 HAR and found self-help that actually works - a true story / Dan Harris. -

52 Officially-Selected Pilots and Series

WOMEN OF COLOR, LATINO COMMUNITIES, MILLENNIALS, AND LESBIAN NUNS: THE NYTVF SELECTS 52 PILOTS FEATURING DIVERSE AND INDEPENDENT VOICES IN A MODERN WORLD *** As Official Artists, pilot creators will enjoy opportunities to pitch, network with, and learn from executives representing the top networks, studios, digital platforms and agencies Official Selections – including 37 World Festival Premieres – to be screened for the public from October 23-28; Industry Passes now on sale [NEW YORK, NY, August 15, 2017] – The NYTVF (www.nytvf.com) today announced the Official Selections for its flagship Independent Pilot Competition (IPC). 52 original television and digital pilots and series will be presented for industry executives and TV fans at the 13th Annual New York Television Festival, October 23-28, 2017 at The Helen Mills Theater and Event Space, with additional Festival events at SVA Theatre. This includes 37 World Festival Premieres. • The slate of in-competition projects represents the NYTVF's most diverse on record, with 56% of all selected pilots featuring persons of color above the line, and 44% with a person of color on the core creative team (creator, writer, director); • 71% of these pilots include a woman in a core creative role - including 50% with a female creator and 38% with a female director (up from 25% in 2016, and the largest number in the Festival’s history); • Nearly a third of selected projects (31%) hail from outside New York or Los Angeles, with international entries from the U.K., Canada, South Africa, and Israel; • Additionally, slightly less than half (46%) of these projects enter competition with no representation. -

English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada

Drawing on the Margins of History: English-Language Graphic Narratives in Canada by Kevin Ziegler A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Kevin Ziegler 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This study analyzes the techniques that Canadian comics life writers develop to construct personal histories. I examine a broad selection of texts including graphic autobiography, biography, memoir, and diary in order to argue that writers and readers can, through these graphic narratives, engage with an eclectic and eccentric understanding of Canadian historical subjects. Contemporary Canadian comics are important for Canadian literature and life writing because they acknowledge the importance of contemporary urban and marginal subcultures and function as representations of people who occasionally experience economic scarcity. I focus on stories of “ordinary” people because their stories have often been excluded from accounts of Canadian public life and cultural history. Following the example of Barbara Godard, Heather Murray, and Roxanne Rimstead, I re- evaluate Canadian literatures by considering the importance of marginal literary products. Canadian comics authors rarely construct narratives about representative figures standing in place of and speaking for a broad community; instead, they create what Murray calls “history with a human face . the face of the daily, the ordinary” (“Literary History as Microhistory” 411). -

List of American Comics Creators 1 List of American Comics Creators

List of American comics creators 1 List of American comics creators This is a list of American comics creators. Although comics have different formats, this list covers creators of comic books, graphic novels and comic strips, along with early innovators. The list presents authors with the United States as their country of origin, although they may have published or now be resident in other countries. For other countries, see List of comic creators. Comic strip creators • Adams, Scott, creator of Dilbert • Ahern, Gene, creator of Our Boarding House, Room and Board, The Squirrel Cage and The Nut Bros. • Andres, Charles, creator of CPU Wars • Berndt, Walter, creator of Smitty • Bishop, Wally, creator of Muggs and Skeeter • Byrnes, Gene, creator of Reg'lar Fellers • Caniff, Milton, creator of Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon • Capp, Al, creator of Li'l Abner • Crane, Roy, creator of Captain Easy and Wash Tubbs • Crespo, Jaime, creator of Life on the Edge of Hell • Davis, Jim, creator of Garfield • Defries, Graham Francis, co-creator of Queens Counsel • Fagan, Kevin, creator of Drabble • Falk, Lee, creator of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician • Fincher, Charles, creator of The Illustrated Daily Scribble and Thadeus & Weez • Griffith, Bill, creator of Zippy • Groening, Matt, creator of Life in Hell • Guindon, Dick, creator of The Carp Chronicles and Guindon • Guisewite, Cathy, creator of Cathy • Hagy, Jessica, creator of Indexed • Hamlin, V. T., creator of Alley Oop • Herriman, George, creator of Krazy Kat • Hess, Sol, creator with -

Facebook, Social Media Privacy, and the Use and Abuse of Data

S. HRG. 115–683 FACEBOOK, SOCIAL MEDIA PRIVACY, AND THE USE AND ABUSE OF DATA JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE AND THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 10, 2018 Serial No. J–115–40 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( Available online: http://www.govinfo.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:24 Nov 08, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 S:\GPO\DOCS\37801.TXT JACKIE FACEBOOK, SOCIAL MEDIA PRIVACY, AND THE USE AND ABUSE OF DATA VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:24 Nov 08, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 S:\GPO\DOCS\37801.TXT JACKIE S. HRG. 115–683 FACEBOOK, SOCIAL MEDIA PRIVACY, AND THE USE AND ABUSE OF DATA JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE AND THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 10, 2018 Serial No. J–115–40 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( Available online: http://www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 37–801 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 09:24 Nov 08, 2019 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\37801.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JOHN THUNE, South Dakota, Chairman ROGER WICKER, Mississippi BILL NELSON, Florida, Ranking ROY BLUNT, Missouri MARIA -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Star Wars Craft Book by Bonnie Burton the Star Wars Craft Book

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Star Wars Craft Book by Bonnie Burton The Star Wars Craft Book. The Star Wars Craft Book is a fully-illustrated, step-by-step guide to creating Star Wars -themed arts and crafts. It was written by Bonnie Burton and published by Del Rey on March 29, 2011. Contents. Product description [ edit | edit source ] GIVE IN TO THE POWER OF THE CRAFTY SIDE. Chewbacca Sock Puppets. Ewok Flower Vases. AT-AT Herb Gardens. With The Star Wars Craft Book, fans of all ages and skill levels can bring the best of the galaxy far, far away right into their own homes. Fully illustrated, this guide features a variety of fun and original projects. • Playtime: Make and play with finger puppets of your favorite cantina characters, Cuddly Banthas, and Rotta the Huttlet Squeaky Toys for your pets • Home Decor: Spruce up your space with Chewbacca Tissue Box Covers, a Mounted Acklay Head, and a Jabba the Hutt Body Pillow • Holiday Crafts: Celebrate festive occasions with Wookiee Pumpkins, Hanukkah Droidels, and a Star Wars Action Figure Wreath • Nature and Science Crafts: Get down to earth with Emperor Appletine Dolls and a Wookiee Bird House • Star Wars Style: Give your wardrobe a dose of intergalactic chic with Ewok Fleece Hats and an R2-D2 Crocheted Beanie. With easy step-by-step instructions, The Star Wars Craft Book is a joyful and entertaining way for you and your friends to bring many beloved elements of Star Wars to life! (No midi-chlorians required!) Interview with Bonnie Burton. We were lucky enough to catch up with the lovely Bonnie Burton this week. -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Loss, Rumination, and Narrative: Chicana/o Melancholy as Generative State Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3w20960q Author Baca, Michelle Patricia Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Loss, Rumination, and Narrative: Chicana/o Melancholy as Generative State A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Chicana and Chicano Studies by Michelle Patricia Baca Committee in Charge: Professor Francisco Lomelí, Chair Professor María Herrera-Sobek Professor Carl Gutierrez-Jones December 2014 The dissertation of Michelle Patricia Baca is approved. María Herrera-Sobek Carl Gutierrez Jones Francisco Lomelí, Chair December 2014 Loss, Rumination, and Narrative: Chicana/o Melancholy as Generative State Copyright © 2014 by Michelle Patricia Baca iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is dedicated to the loving tribe that is comprised of my family, friends, teachers, and colleagues. Thanks to this bunch I’ve been blessed with love, support, and the complete confidence that I could do anything I set my mind to. Thank you to my parents, Mama and Dad I wouldn’t be who I am without you. I wouldn’t be where I am without you. Thank you to Joe, the best brother in the world. Thank you to my teachers, all of them ever. Thank you to my colleagues and friends. Thank you for inspiring me, challenging me, and supporting me. Thank you to Justin, my partner in life and love. Thank you for bearing with me, and being proud of me. -

Conceptions of Authenticity in Fashion Blogging

“They're really profound women, they're entrepreneurs”: Conceptions of Authenticity in Fashion Blogging Alice E. Marwick Department of Communication & Media Studies Fordham University Bronx, New York, USA [email protected] Abstract Repeller and Tavi Gevinson of Style Rookie, are courted by Fashion blogging is an international subculture comprised designers and receive invitations to fashion shows, free primarily of young women who post photographs of clothes, and opportunities to collaborate with fashion themselves and their possessions, comment on clothes and brands. Magazines like Lucky and Elle feature fashion fashion, and use self-branding techniques to promote spreads inspired by and starring fashion bloggers. The themselves and their blogs. Drawing from ethnographic interviews with 30 participants, I examine how fashion bloggers behind The Sartorialist, What I Wore, and bloggers use “authenticity” as an organizing principle to Facehunter have published books of their photographs and differentiate “good” fashion blogs from “bad” fashion blogs. commentary. As the benefits accruing to successful fashion “Authenticity” is positioned as an invaluable, yet ineffable bloggers mount, more women—fashion bloggers are quality which differentiates fashion blogging from its overwhelmingly female—are starting fashion blogs. There mainstream media counterparts, like fashion magazines and runway shows, in two ways. First, authenticity describes a are fashion bloggers in virtually every city in the United set of affective relations between bloggers and their readers. States, and fashion bloggers hold meetups and “tweet ups” Second, despite previous studies which have positioned in cities around the world. “authenticity” as antithetical to branding and commodification, fashion bloggers see authenticity and Fashion bloggers and their readers often consider blogs commercial interests as potentially, but not necessarily, to be more authentic, individualistic, and independent than consistent. -

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE of DENIS KITCHEN Spring 2014 • the New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 Table of Contents

THE COMIX BOOK LIFE OF DENIS KITCHEN 0 2 1 82658 97073 4 in theUSA $ 8.95 ADULTS ONLY! A TwoMorrows Publication TwoMorrows Cover art byDenisKitchen No. 5,Spring2014 ™ Spring 2014 • The New Voice of the Comics Medium • Number 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS HIPPIE W©©DY Ye Ed’s Rant: Talking up Kitchen, Wild Bill, Cruse, and upcoming CBC changes ............ 2 CBC mascot by J.D. KING ©2014 J.D. King. COMICS CHATTER About Our Bob Fingerman: The cartoonist is slaving for his monthly Minimum Wage .................. 3 Cover Incoming: Neal Adams and CBC’s editor take a sound thrashing from readers ............. 8 Art by DENIS KITCHEN The Good Stuff: Jorge Khoury on artist Frank Espinosa’s latest triumph ..................... 12 Color by BR YANT PAUL Hembeck’s Dateline: Our Man Fred recalls his Kitchen Sink contributions ................ 14 JOHNSON Coming Soon in CBC: Howard Cruse, Vanguard Cartoonist Announcement that Ye Ed’s comprehensive talk with the 2014 MOCCA guest of honor and award-winning author of Stuck Rubber Baby will be coming this fall...... 15 REMEMBERING WILD BILL EVERETT The Last Splash: Blake Bell traces the final, glorious years of Bill Everett and the man’s exquisite final run on Sub-Mariner in a poignant, sober crescendo of life ..... 16 Fish Stories: Separating the facts from myth regarding William Blake Everett ........... 23 Cowan Considered: Part two of Michael Aushenker’s interview with Denys Cowan on the man’s years in cartoon animation and a triumphant return to comics ............ 24 Art ©2014 Denis Kitchen. Dr. Wertham’s Sloppy Seduction: Prof. Carol L. Tilley discusses her findings of DENIS KITCHEN included three shoddy research and falsified evidence inSeduction of the Innocent, the notorious in-jokes on our cover that his observant close friends might book that almost took down the entire comic book industry .................................... -

Obamals State of the Union

TODAY’s WEATHER NEWS SPORTS Supreme Court denies to The Sports Staff analyzes hear appeal to recognize the Commodores’ continuing Vanderbilt scientists struggles away from home SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 7 Snow, 36 / 25 THE VANDERBILT HUSTLER THE VOICE OF VANDERBILT SINCE 1888 LIFE EDITION WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 26, 2011 WWW .INSIDEVANDY.COM 123RD YEAR, NO. 7 The NATIONAL NEWS NEWfaces Obama’s State of of the Union: FASHION ‘Move forward With the introduction of homegrown fashion blogs, such as CollegeFashionista, new faces together or are occupying front row seats and gaining momentum in the industry. not at all’ KYLE BLAINE OLIVIA KUPFER News Editor other initiatives in his speech. Life Editor He pointed to the transportation Vanderbilt students watched on and construction projects of Tuesday night as President Barack the last two years and proposed The fashion industry — with Obama delivered his State of the “we redouble these efforts.” He capitals in New York, Paris and Union address, pleading for unity coupled this with a call to “freeze Milan — used to represent an in a newly divided government. annual domestic spending for the inaccessible world for the masses. He implored Democratic and next five years.” Less than ten years ago, the Republican lawmakers to rally Yet, Republicans have dismissed average 20-something couldn’t behind his vision of economic his “investment” proposals as attend an international fashion revival, declaring in his State of merely new spending. week and was unqualified to write the Union address: “We will move “The president should be about the industry. forward together or not at all.” ashamed for disguising his Today, the once impenetrable Setting a tone of commonality continued out-of-control fashion industry is accessible to by invoking the name of Rep. -

Elif Batuman

ELIF BATUMAN “Batuman's writing waltzes in a space in which books and life reflect each other.” —Los Angeles Times Elif Batuman’s writing has been described as helplessly witty and concise. She’s a staff writer for The New Yorker and has published two critically acclaimed books – The Possessed and The Idiot, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2018. Elif graduated from Harvard College and has a PhD in comparative literature from Stanford University. During graduate school she studied in Uzbekistan, and from 2010 to 2013, she was a writer-in-residence at Koç University, in Istanbul. The Possessed is a collection of comic interconnected non-fiction essays about the pursuit of Russian literature. It was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the New York Times praises the book as, “hilarious, wide-ranging, erudite, and memorable, The Possessed is a sui generis feast for the mind and the fancy, ants and all.” The Idiot is a novel set in 1995 that observes the rise of internet culture and language’s inability to communicate feelings or ideas accurately. Author Mary Karl praises The Idiot, saying, “this book is a bold, unforgettable, un-put-downable read by a new master stylist. Best book I’ve read in years.” Elif is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award, a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, and a Paris Review Terry Southern Prize for Humor. She lives in Brooklyn, New York where she is hard at work writing her third book. 404 East College Street, Suite 408 · Iowa City Iowa · 52240 office 319- 338-7080 · [email protected] · tuesdayagency.com.