The Origins and Sequences of Civilizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected]

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 7 Number 2 Pervuvian Trajectories of Sociocultural Article 13 Transformation December 2013 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Silva, Ernesto (2013) "Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 7 : No. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol7/iss2/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Emesto Silva Journal of Global Initiatives Volume 7, umber 2, 2012, pp. l83-197 Epilogue: Reflections and Observations on Peru's Past and Present Ernesto Silva 1 The aim of this essay is to provide a panoramic socio-historical overview of Peru by focusing on two periods: before and after independence from Spain. The approach emphasizes two cultural phenomena: how the indigenous peo ple related to the Conquistadors in forging a new society, as well as how im migration, particularly to Lima, has shaped contemporary Peru. This contribu tion also aims at providing a bibliographical resource to those who would like to conduct research on Peru. -

Agave Beverage

● ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES Agave salmiana Waiting for the sunrise ‘Tequila to wake the living; mezcal to wake the dead’ - old Mexican proverb. Before corn was ever domesticated, agaves (Agave spp.) identifi ed it with a similar plant found at home. Agaves fl ower only once (‘mono- were one of the main carbohydrate sources for humans carpic’), usually after they are between in what is today western and northern Mexico and south- 8-10 years old, and the plant will then die if allowed to set seed. This trait gives western US. Agaves (or magueyes) are perennial, short- rise to their alternative name of ‘century stemmed, monocotyledonous succulents, with a fl eshy leaf plants’. Archaeological evidence indicates base and stem. that agave stems and leaf bases (the ‘heads’, or ‘cores’) and fl owering stems By Ian Hornsey and ’ixcaloa’ (to cook). The name applies have been pit-cooked for eating in Mes- to at least 100 Mexican liquors that oamerica since at least 9,000 BC. When hey belong to the family Agavaceae, have been distilled with alembics or they arrived, the Spaniards noted that Twhich is endemic to America and Asian-type stills. Alcoholic drinks from native peoples produced ‘agave wine’ whose centre of diversity is Mexico. agaves can be divided into two groups, although their writings do not make it Nearly 200 spp. have been described, according to treatment of the plant: ’cut clear whether this referred to ‘ferment- 150 of them from Mexico, and around bud-tip drinks’ and ’baked plant core ed’ or ‘distilled’ beverages. This is partly 75 are used in that country for human drinks’. -

First Civilizations Cities, States, and Unequal Societies 3500 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E

c h a p t e r t h r e e First Civilizations Cities, States, and Unequal Societies 3500 B.C.E.–500 B.C.E. “Over 100 miles of wilderness, deep exploration into pristine lands, the solitude of backcountry camping, 4-4 trails, and ancient American Indian rock art and ruins. You can’t find a better way to escape civilization!”1 So goes an advertisement for a vacation in Utah’s Canyonlands National Park, one of thousands of similar attempts to lure apparently constrained, beleaguered, and “civilized” city-dwellers into the spacious freedom of the wild and the imagined simplicity of earlier times. This urge to “escape from civilization” has long been a central feature in modern life. It is a major theme in Mark Twain’s famous novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, in which the restless and rebellious Huck resists all efforts to “civilize” him by fleeing to the freedom of life on the river. It is a large part of the “cowboy” image in American culture, and it permeates environmentalist efforts to protect the remaining wilderness areas of the country. Nor has this impulse been limited to modern societies and the Western world. The ancient Chinese teachers of Daoism likewise urged their followers to abandon the structured and demanding world of urban and civilized life and to immerse themselves in the eternal patterns of the natural order. It is a strange paradox that we count the creation of civilization among the major achievements of humankind and yet people within these civilizations have often sought to escape the constraints, artificiality, hierarchies, and other discontents of city living. -

Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes Charles Ortloff [email protected]

Andean Past Volume 9 Article 15 11-1-2009 Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes Charles Ortloff [email protected] Michael E. Moseley University of Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Sustainability Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Ortloff, Charles and Moseley, Michael E. (2009) "Climate, Agricultural Strategies, and Sustainability in the Precolumbian Andes," Andean Past: Vol. 9 , Article 15. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol9/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLIMATE, AGRICULTURAL STATEGIES, AND SUSTAINABILITY IN THE PRECOLUMBIAN ANDES CHARLES R. ORTLOFF University of Chicago and MICHAEL E. MOSELEY University of Florida INTRODUCTION allowed each society to design and manage complex water supply networks and to adapt Throughout ancient South America, mil- them as climate changed. While shifts to marine lions of hectares of abandoned farmland attest resources, pastoralism, and trade may have that much more terrain was cultivated in mitigated declines in agricultural production, precolumbian times than at present. For Peru damage to the sustainability of the main agricul- alone, the millions of hectares of abandoned tural system often led to societal changes and/or agricultural land show that in some regions 30 additional modifications to those systems. -

Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor

Silva Collins, Gabriel 2019 Anthropology Thesis Title: Making the Mountains: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads Advisor: Antonia Foias Advisor is Co-author: None of the above Second Advisor: Released: release now Authenticated User Access: No Contains Copyrighted Material: No MAKING THE MOUNTAINS: Inca Statehood on the Huchuy Qosqo Roads by GABRIEL SILVA COLLINS Antonia Foias, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Anthropology WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts May 19, 2019 Introduction Peru is famous for its Pre-Hispanic archaeological sites: places like Machu Picchu, the Nazca lines, and the city of Chan Chan. Ranging from the earliest cities in the Americas to Inca metropolises, millennia of urban human history along the Andes have left large and striking sites scattered across the country. But cities and monuments do not exist in solitude. Peru’s ancient sites are connected by a vast circulatory system of roads that connected every corner of the country, and thousands of square miles beyond its current borders. The Inca road system, or Qhapaq Ñan, is particularly famous; thousands of miles of trails linked the empire from modern- day Colombia to central Chile, crossing some of the world’s tallest mountain ranges and driest deserts. The Inca state recognized the importance of its road system, and dotted the trails with rest stops, granaries, and religious shrines. Inca roads even served directly religious purposes in pilgrimages and a system of ritual pathways that divided the empire (Ogburn 2010). This project contributes to scholarly knowledge about the Inca and Pre-Hispanic Andean civilizations by studying the roads which stitched together the Inca state. -

Adeuda El Ingenio $300 Millones a Cañeros

( Reducir la Deuda y Créditos Nuevos Requiere México (INFORMACION COLS . 1 Y 8) 'HOTELAMERICA' -1-' . ' &--&-- SUANFITRION.EN COLIMA MORELOS No . 162 /(a TELS. 2 .0366 Y 2 .95 .96 o~ima COLIMA, COL ., MEX . Fundador Director General Año Colima, Col ., Jueves 16 de Marzo de 1989 . Número XXXV Manuel Sánchez Silva Héctor Sánchez de la Madrid 11,467 Adeuda el Ingenio $300 Millones a Cañeros os Costos del Corte de Caña Provocan Cuevas Isáis : pérdidas por 200 Millones de Pesos Pésimas Ventas en Restaurantes • Situación insólita en la vida de la factoría : Romero Velasco . Cayeron en un 40% • Falso que se mejore punto de sacarosa con ese tipo de corte "Las ventas en la in- dustria restaurantera local I Se ha reducido en 20% el ritmo de molienda por el problema son pésimas, pues han Por Héctor Espinosa Flores decaído en un 40 por ciento, pero pensamos que en esta Independientemente de los problemas tema de corte de la caña se tendrá un me- temporada vacacional de que ha ocasionado la disposición de modi- jor aprovechamiento y por lo tanto un me- Semana Santa y Pascua nos ficar la técnica del corte de caña y que ha jor rendimiento de punto de sacarosa arri- nivelaremos con la llegada a provocado pérdidas a los productores por ba del 8.3 por ciento, pero hasta ahora no Colima de muchos turistas 200 millones de pesos, ahora el ingenio de se ha llegado ni al 8 por ciento, por lo que foráneos aunque no abusa- Quesería tiene un adeudo de 300 millones los productores están confirmando que remos, porque los precios de pesos de la primera preliquidación, al- ese sistema beneflcla, sino que perjudica . -

Estado De Yucatán

119 CUADRO 9." POBLACION TOTAL SEGUN SU RELIGION, POR SEXO POBLACION PROTESTANTE MUNICIPIO Y SEXO TOTAL CATOLICA 0 ISRAELITA OTRA NINGUNA EVANGELICA MAMA 1 482 1 470 11 1 húKBKES 757 752 4 1 MLJcRES 725 718 7 HANI 2 598 2 401 189 3 5 HCMBRtS 1 2 3ü 1 129 96 1 4 MLJtKcS 1 368 1 2 72 93 2 1 MAXCANL 1C SoC 1C 206 64 3 10 27 7 kCMbRES 5 179 4 988 38 1 5 147 ML JERE 3 i 3ól í 218 26 2 5 130 tlAYAPAN 1 CC4 94C 3 61 HOMJjíl-S 5C2 465 2 35 MUJtRtS 5C2 475 1 26 MtRIDA 241 Sí4 234 213 4 188 76 838 2 649 HÜMBRtS 117 12a 112 996 1 963 35 448 1 684 MUJERES 124 6je 121 215 2 225 41 390 965 PÚCUChA 1 523 1 ¡369 33 21 HJMdRES 1 C21 966 17 16 MLJERtS 902 883 16 3 MGTUL 2C 994 19 788 602 12 24 568 l-OHSKÍS U CLC 5 344 297 9 17 333 MUJERES 1C S94 1C 44* 3C5 7 235 MUÑA 6 k.12 5 709 179 1 123 hJP3KES 2 5u5 2 763 77 65 MUJERES i 1C7 2 946 1C2 1 58 MUXUPIP 1 EJ7 1 8C9 2 26 Hü MdR E S 935 914 1 20 MUJ E Rt S sc¿ 895 ] 6 GPICHEN ¿ Eia 2 538 19 1 HOMtíKtS 949 54 L 9 MUJERES 1 60 9 1 598 10 1 ÍXXUT2CAE 1C 35b 9 529 488 20 318 HOMBRES 4 7 i 1 4 296 251 11 173 MUJERES 5 624 5 233 237 9 145 PANABA 4 216 3 964 192 6 53 HOMüRcS 1 832 1 7C5 92 5 30 MUJERES 2 384 2 259 1C1 1 23 PE Tu 12 lis 11 ¢57 J52 1 12 163 HOMdREi 6 6 016 195 1 6 88 MUJERES 5 i¡79 i 641 157 6 75 PROGRESO 21 352 2C 131 74C 1 61 419 HLMdKE S 1C 1U2 9 482 348 1 30 241 MUJEKES 11 2 50 1C 649 392 31 178 CUINTANA RUO €69 5C2 366 HÚM3RES 477 2 74 20 3 MUJERES 392 229 163 RIC LAGARTOS 1 705 1 669 11 24 HLMdRES 692 87C 1C 12 MUJERES 813 759 1 12 SACALUM 2 457 2 355 54 48 HUMBAtá 1 201 1 244 32 25 1971 MUJERti 1 156 1 111 22 23 SAMAhlL 2 460 2 410 44 2 4 hCHBftES 1 362 1 335 24 1 2 Yucatán. -

Guadalajara Metropolitana Oportunidades Y Propuestas Prosperidad Urbana: D Oportunidades Y Propuestas

G PROSPERIDAD METROPOLITANA URBANA: GUADALAJARA METROPOLITANA OPORTUNIDADES Y PROPUESTAS PROSPERIDAD URBANA: D OPORTUNIDADES Y PROPUESTAS L PROSPERIDAD URBANA: OPORTUNIDADES Y PROPUESTAS GUADALAJARA METROPOLITANA GUADALAJARA Guadalajara Metropolitana Prosperidad urbana: oportunidades y propuestas Introducción 3 Guadalajara Metropolitana Proyecto: Prosperidad urbana: oportunidades y propuestas Acuerdo de Contribución entre el Programa de las Naciones Unidas para los Asentamientos Humanos (ONU-Habitat) y Derechos reservados 2017 el Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco. © Programa de las Naciones Unidas para los Consultores: Asentamientos Humanos, ONU-Habitat Sergio García de Alba, Luis F. Siqueiros, Víctor Ortiz, Av. Paseo de la Reforma 99, PB. Agustín Escobar, Eduardo Santana, Oliver Meza, Adriana Col. Tabacalera, CP. 06030, Ciudad de México. Olivares, Guillermo Woo, Luis Valdivia, Héctor Castañón, Tel. +52 (55) 6820-9700 ext. 40062 Daniel González. HS Number: HS/004/17S Colaboradores: ISBN Number: (Volume) 978-92-1-132726-7 Laura Pedraza, Diego Escobar, Néstor Platero, Rodrigo Flores, Gerardo Bernache, Mauricio Alcocer, Mario García, Se prohíbe la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra, Sergio Graf, Gabriel Corona, Verónica Díaz, Marco Medina, sea cual fuere el medio, sin el consentimiento por escrito Jesús Rodríguez, Carlos Marmolejo. del titular de los derechos. Exención de responsabilidad: Joan Clos Las designaciones empleadas y la presentación del Director Ejecutivo de ONU-Habitat material en el presente informe no implican la expresión de ninguna manera de la Secretaría de las Naciones Elkin Velásquez Unidas con referencia al estatus legal de cualquier país, Director Regional de ONU-Habitat para América Latina y territorio, ciudad o área, o de sus autoridades, o relativas el Caribe a la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites, o en lo que hace a sus sistemas económicos o grado de desarrollo. -

Conquista-Dores E Coronistas: As Primeiras Narrativas Sobre O Novo Reino De Granada

1 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA CONQUISTA-DORES E CORONISTAS: AS PRIMEIRAS NARRATIVAS SOBRE O NOVO REINO DE GRANADA JUAN DAVID FIGUEROA CANCINO BRASÍLIA 2016 2 JUAN DAVID FIGUEROA CANCINO CONQUISTA-DORES E CORONISTAS: AS PRIMEIRAS NARRATIVAS SOBRE O NOVO REINO DE GRANADA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós- graduação em História da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor em História. Linha de pesquisa: História cultural, Memórias e Identidades. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Jaime de Almeida BRASÍLIA 2016 3 Às minhas avós e meus avôs, que nasceram e viveram na região dos muíscas: Maria Cecilia, Nina, Miguel Antonio e José Ignacio 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Desejo expressar minha profunda gratidão a todas as pessoas e instituições que me ajudaram de mil e uma formas a completar satisfatoriamente o doutorado: A meu orientador, o prof. Dr. Jaime de Almeida, por ter recebido com entusiasmo desde o começo a iniciativa de desenvolver minha tese sob sua orientação; pela paciência e tolerância com as mudanças do tema; pela leitura cuidadosa, os valiosos comentários e sugestões; e também porque ele e sua querida esposa Marli se esforçaram para que minha estadia no Brasil fosse o mais agradável possível, tanto no DF como em sua linda casa de Ipameri. Aos membros da banca final pelas importantes contribuições para o aprimoramento da pesquisa: os profs. Drs. Anna Herron More, Susane Rodrigues de Oliveira, José Alves de Freitas Neto e Alberto Baena Zapatero. Aos profs. Drs. Estevão Chaves de Rezende e João Paulo Garrido Pimenta pela leitura cuidadosa e as sugestões durante o exame geral de qualificação, embora as partes do trabalho que eles examinaram tenham mudado em escopo e temática. -

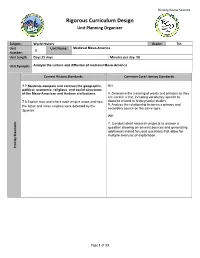

Rigorous Curriculum Design Unit Planning Organizer

History/Social Science Rigorous Curriculum Design Unit Planning Organizer Subject: World History Grade: 7th Unit Unit Name: Medieval Meso-America 3 Number: Unit Length Days:15 days Minutes per day: 50 Unit Synopsis Analyze the culture and diffusion of medieval Meso-America Current History Standards Common Core Literacy Standards 7.7 Students compare and contrast the geographic, RH political, economic, religious, and social structures of the Meso-American and Andean civilizations. 4. Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to 7.3 Explain how and where each empire arose and how domains related to history/social studies the Aztec and Incan empires were defeated by the 9. Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic. Spanish. WH 7. Conduct short research projects to answer a question drawing on several sources and generating additional related focused questions that allow for Standards multiple avenues of exploration. Priority Page 1 of 13 History/Social Science Common Core Literacy Standards Current History Standards RH 7.7 Students compare and contrast the geographic, political, economic, religious, and social structures 3. Identify key steps in a text’s description of a process of the Meso-American and Andean civilizations. related to history/social studies (e.g., how a bill becomes law, how interest rates are raised or lowered). Standards .1 Study the locations, landforms, and climates of 5. Describe how a text presents information (e.g., Mexico, Central America, and South America and their sequentially, comparatively, causally). effects on Mayan, Aztec, and Incan economies, trade, 6. -

00-ARQUEOLOGIA 43-INDICE.Pmd

85 LAS CERÁMICAS TEMPRANAS EN EL ÁREA DEL DELTA DEL BALSAS Ma. de Lourdes López Camacho* Salvador Pulido Méndez** Las cerámicas tempranas en el área del delta del Balsas Los trabajos de investigación que hemos llevado a cabo en la desembocadura del río Balsas han dado algunas gratas sorpresas, entre ellas las relacionadas con los materiales cerámicos que atestiguan y son producto de un desarrollo social profundamente enraizado en el devenir de la región. En este escrito deseamos propiciar la reflexión sobre las cerámicas tempranas ubicadas en dicha área y sus relaciones con otras zonas culturales cercanas y lejanas. En este sentido retomamos algunos de los argumentos que desde mediados del siglo pasado se esbo- zaron sobre la conformación de un área cultural primigenia que abarcó regiones más allá de los límites de nuestro país y de lo que se conoce como Mesoamérica. Por otra parte, publicamos los materiales propios de la zona de nuestra investigación, a fin de que contribuyan a la difícil tarea de lograr una visión plausible sobre el desarrollo de los primeros grupos humanos de la América media. Archaeological work conducted at the mouth of the Balsas River have produced pleasant surprises, some of them related to ceramics that attest to and are the product of social process deeply rooted in the region’s development. In this paper we wish to promote reflection on early ceramics located in this zone and their relations with other nearby and distant cultural areas. In this line of thinking, we revive some of the ideas put forth since the mid-twentieth century that outlined the formation of an original cultural area that encompassed zones beyond the current borders of Mexico and what is known as Mesoamerica. -

Cultural Traditions of Ancient Mesoamerica Michael Shaw

FINDLAY Cultural Traditions of Cultural Traditions of Ancient Mesoamerica Ancient Mesoamerica Cultural Traditions of Ancient Mesoamerica describes ancient cultural traditions of the ofCultural Traditions Ancient Mesoamerica Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, and Aztecs, among others, providing students with a survey of EDITION Precontact Mesoamerica. The text features a multidisciplinary approach, including perspectives from archaeology, cultural history, epigraphy, art history, and ethnography. The book is organized into ten chapters and proceeds in roughly chronological order to reflect developmental changes in Mesoamerican culture from around 16kya to A.D. 1492. The opening chapter summarizes the foundational concerns of Mesoamerican studies. Chapters Two and Three explore the cultural development of Mesoamerica from the first migrations into the Americas to the Preclassic period. Chapter Four discusses various theories pertaining to culture change. In Chapters Five and Six, students examine Mesoamerica’s Classic period. Chapter Seven outlines the nature and importance of ancient and post-contact books and pictorial documents to the study of Mesoamerica. In Chapters Eight and Nine, students learn about the Classic Collapse, the Terminal Classic period, and the Post-Classic period. The final chapter describes the Spanish impact on Native Mesoamerican culture. Cultural Traditions of Ancient Mesoamerica is well suited for courses in anthropology, archaeology, ancient civilizations, ancient Mesoamerica, Latin American history, and Latin American studies. Michael Shaw Findlay earned his Ph.D. in curriculum/instruction in the Anthropology of Education Program at the University of Oregon. He has over 30 years of experience teaching at the secondary and post-secondary levels, including his work at California State University, Chico, and Butte College.