Birgel 2002.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

Lange Nacht Der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER

31 AUG 13 | 18—2 UHR Lange Nacht der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER Museumsinformation Berlin (030) 24 74 98 88 www.lange-nacht-der- M u s e e n . d e präsentiert von OLD MASTERS & YOUNG REBELS Age has occupied man since the beginning of time Cranach’s »Fountain of Youth«. Many other loca- – even if now, with Europe facing an ageing popula- tions display different expression of youth culture tion and youth unemployment, it is more relevant or young artist’s protests: Mail Art in the Akademie than ever. As far back as antiquity we find unsparing der Künste, street art in the Kreuzberg Museum, depictions of old age alongside ideal figures of breakdance in the Deutsches Historisches Museum young athletes. Painters and sculptors in every and graffiti at Lustgarten. epoch have tackled this theme, demonstrating their The new additions to the Long Night programme – virtuosity in the characterisation of the stages of the Skateboard Museum, the Generation 13 muse- life. In history, each new generation has attempted um and the Ramones Museum, dedicated to the to reform society; on a smaller scale, the conflict New York punk band – especially convey the atti- between young and old has always shaped the fami- tude of a generation. There has also been a genera- ly unit – no differently amongst the ruling classes tion change in our team: Wolf Kühnelt, who came up than the common people. with the idea of the Long Night of Museums and The participating museums have creatively picked who kept it vibrant over many years, has passed on up the Long Night theme – in exhibitions, guided the management of the project.We all want to thank tours, films, talks and music. -

Chapter 11), Making the Events That Occur Within the Time and Space Of

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION: IN PRAISE OF BABBITTRY. SORT OF. SPATIAL PRACTICES IN SUBURBIA Kenneth Jackson’s Crabgrass Frontiers, one of the key histories of American suburbia, marshals a fascinating array of evidence from sociology, geography, real estate literature, union membership profiles, the popular press and census information to represent the American suburbs in terms of population density, home-ownership, and residential status. But even as it notes that “nothing over the years has succeeded in gluing this automobile-oriented civilization into any kind of cohesion – save that of individual routine,” Jackson’s comprehensive history under-analyzes one of its four key suburban traits – the journey-to-work.1 It is difficult to account for the paucity of engagements with suburban transportation and everyday experiences like commuting, even in excellent histories like Jackson’s. In 2005, the average American spent slightly more than twenty-five minutes per day commuting, a time investment that, over the course of a year, translates to more time commuting than he or she will likely spend on vacation.2 Highway-dependent suburban sprawl perpetually moves farther across the map in search of cheap available land, often moving away from both traditional central 1 In the introduction, Jackson describes journey-to-work’s place in suburbia with average travel time and distance in opposition to South America (home of siestas) and Europe, asserting that “an easier connection between work and residence is more valued and achieved in other cultures” (10). 2 One 2003 news report calculates the commuting-to-vacation ratio at 5-to-4: “Americans spend more than 100 hours commuting to work each year, according to American Community Survey (ACS) data released today by the U.S. -

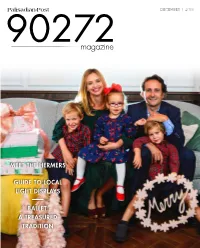

December | 2018 Lacarguy.Com

december | 2018 LAcarGUY.com 1501 Santa Monica Blvd Santa Monica, CA 90404 · (424)322-1110 2 year maintenance from now until the end of the year! 2019 NX 300 2018 RXL HYBRID AWD 2018 RXL 350 $ $3999 $ $3999 $ $3999 329/mo. DUE AT SIGNING 469/mo. DUE AT SIGNING 439 /mo. DUE AT SIGNING 801 Santa Monica Blvd · Santa Monica, CA 90401 · (424)291-4884 2019 CoRoLLA LE 2018 MIRAI 2018 RAV4 LE $ $1999 $ $2499 $ $1999 199/mo. DUE AT SIGNING 349/mo. DUE AT SIGNING 239/mo. DUE AT SIGNING 2 CONTENTS Holidays with the Hermers Holiday Gift 5 Matt and Marissa Hermer, 38 Recommendations with their three children, Max, Sadie from Amazon Books and Jake, have holiday traditions The Palisades Village spot shares that stretch from London to some of its selections for gifts this the Palisades. holiday season. Dancing for the Holidays All the Pretty Lights 14 Palisades Ballet Conservato- 40 From Newport Beach to ry West and Westside Ballet of Santa the Palisades, there is no shortage of Monica—two local conservancies— holiday light displays this season. share what makes their holiday-time productions so special. Mark Your Calendar 05 44 Here are 90272 Magazine’s Enjoy the Show suggestions for things to do this 20 Ten movie recommenda- December. tions for when you need a break from holiday-themed fun. Picture-Perfect Palisades 47 A glimpse at what makes Sweet and Festive Treats our town so special. 14 40 22 Looking to bake something sweet? Try out these cookie recipes. Holiday Magic Gift Guide I can’t say this enough: I love the holidays. -

Film Policies and Cinema Audiences in Germany

Claudia Dillmann Film Policies and Cinema Audiences in Germany Abstract After the war German cinema was by no means free, neither during the period of military occupation nor after the foundation of the two German states in 1949. While the Soviet Union’s film policy in Eastern Germany had set the course for the monopolization of film production, the Western Allies under the leadership of the USA had insisted on the destruction of the former Nazi film monopoly structures. With the beginning of the Cold War, the Federal Republic sought to exert a direct but hidden influence on the mass media, even though the constitution of the young democracy prohibited censorship: the state brought the most important newsreel under its control, exercised censorship, intervened in the film market and tried to re-establish cartels. As in Eastern Germany, the medium was to be ideologically rearmed which led to a complex network determined by political, ideological, economic and socio-cultural factors. This overview aims at putting the individual influencing factors in relation to one another. In doing so, a context is presented and analyzed that can shed light on the much-discussed continuities between the Nazi and the West-German cinema. There was indeed a “zero hour”: in the structure of the industry and the system of financing film production, in a new aesthetic and a new attitude. But there also have been continuities: in the political view on the propagandistic effect of film and the suggestibility of the masses, and also in reception when these masses pushed through their favor for pre-1945 films, with far-reaching consequences. -

Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination : Set Design in 1930S European Cinema 2007

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Tim Bergfelder; Sue Harris; Sarah Street Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination : Set Design in 1930s European Cinema 2007 https://doi.org/10.5117/9789053569801 Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bergfelder, Tim; Harris, Sue; Street, Sarah: Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination : Set Design in 1930s European Cinema. Amsterdam University Press 2007 (Film Culture in Transition). DOI: https://doi.org/10.5117/9789053569801. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons BY-NC 3.0/ This document is made available under a creative commons BY- Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz NC 3.0/ License. For more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ * hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. -

Herbert Windt (1894-1965)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 4, 2010 / 209 Herbert Windt (1894-1965) Herbert Windt wurde am 15.9.1894 in Senftenberg in der Niederlausitz als Sohn eines Kaufmanns geboren. Seine Familie war sehr musikalisch veranlagt und brachte ihn schon früh zum Klavierspiel und zum Notenstudium. Als junger Mann verließ er die Schule und ging 1910 an das Sternsche Konservatorium, wo er bis zu seiner freiwilligen Meldung zur Teilnahme am Ersten Weltkrieg im Sommer 1914 studierte. 1917 wurde er als Feldwebel bei Verdun so schwer verwundet, dass er zu 75% als kriegsbeschädigt galt und eine Karriere als Dirigent oder Pianist nicht mehr in Frage kam. Windt studierte daher ab 1921 unter dem renommierten Opernkomponisten Franz Schreker an der Hochschule für Musik in Berlin weiter und widmete sich zusehends eigenen Kompositionen, von denen die Oper Andromache (1932) die bedeutendste ist (obgleich sie nur vier Aufführungen erlebte). Windt wandte sich früh den neuen Medien zu und vertonte u.a. einen Flug Hitlers von Ostpreußen zum Niederwald als Funkkantate (1937). Er war seit November 1931 Mitglied der NSDAP und in nationalkonservativen Kreisen so bekannt, dass ihm in diesen eine Vielzahl an Aufträgen in Film, Rundfunk und Fernsehen verschafft wurde. Seine erste abendfüllende Spielfilmmusik zu dem Film MORGENROT (1933), zugleich der erste Film nach der Machtergreifung, sowie weitere Aufträge ließen ihn schnell zum Spezialisten für „heroische“ und „nationale“ Filmmusiken werden (was sich u.a. in einer intensiven Nutzung populärer Wagner-Motive niederschlägt). Seine Musik ist mikro-motivisch orientiert und rhythmisch präzise durchgestaltet, zudem genau auf die Dramaturgie der Filme abgestimmt. -

The Parent Trap Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE PARENT TRAP PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Erich Kästner,Anthea Bell,Walter Trier,Nathan Burton | 144 pages | 02 Jan 2015 | Pushkin Children's Books | 9781782690559 | English | London, United Kingdom The Parent Trap PDF Book Nominated for 2 Oscars. Retrieved August 16, They are already reciting it. Alternate Versions. Jeffrey Wyatt. On April 24, , the film was released for the first time on Blu-ray, but as a Disney Movie Club exclusive. Written by Kelly. July 20, Technical Specs. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Dream Come True. Cook , and the other for Film Editing by Philip W. Sherman Robert B. Disney Channel Original Movies. Hayley Mills again reprises her roles as twins Sharon and Susan, with Barry Bostwick as a father of triplet girls and Patricia Richardson as his snobbish girlfriend. Exasperated, Vicky finally has a shouting tantrum, destroying everything in her path. When Vicky escapes back to the city in a great huff, Mitch seems none too worried to be rid of her. Main article: The Parent Trap film. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Use the HTML below. Simon and Schuster. The Christian Science Monitor 11 Oct 7. Technical Specs. The parents of the twins, Nick Parker played by Dennis Quaid and Elizabeth James played by Natasha Richardson , marry on a cruise ship and quickly figure out their lives are in two separate places. Edit Did You Know? Retrieved May 1, User Polls Just the two of us Jazz Latin New Age. Ebert, Roger July 29, February 21, Susan and Sharon try to find a way to delay their return to Boston, so the twins dress and talk alike so their parents are unable to tell them apart. -

Der Kinematograph (October 1926)

'^0 GEBÜHR. ALS KOMMANDANT DES UNIENSCHiFFES, HESSEN" ' NEUEN EIKO-MARINE - FILM DER NATION AL-F iLM A.-G. * IN TREUE STARK » . ' Verlorene miiiiiy iPiiiiiiiiiiiiiiKiiiifii.'iii.iiiiiiiiitiiBwiiiMiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiHiiiiiii'iiiiiiiiiiiaimiiiiiiiniii AU CHTE tmmmmmmimmmmmmMmtmmmKmmmmBii Drama in ö Akten aus dem Künstlerleben Regie: Graf Friedr. Carl Perponcßer Hauptdarsteller: Carola Jäger, Eßmi Bessel, Adolf Jeß, Waller Neumann vom Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus Pßofograpßie: Hans Scßeib 'Reic£>ss:en&iert Hersteller : TOSCA-TILM g. m. b. h„ Düsseldorf Alleinvertrieb: Ludwig Rrager 81 Co. am.b.H Berlin SW Aö, Friedricßsiraße lö Telefon: Dönhoff 693, 6Ö2 Telegr.-Adr.: Gegart . REGIE: HENRIK GALEEN c o N n a D V e i z> 1 4CJVES ESTERHAXY WERKEUKUAVSS Er.IT.7A CA T»ORTA SONDBR= VERLEIH BERLIN SW4fl. FRIEDRICHSTP ASSF PA' HASFNHEIDfi 70Ö1-PÄ Ktnrttuttogrnph Rinrmntogrnph DIE UFA'VERLEIH'BETRIEBE BRINGEN ALS ERSTE FOLGE IM PRODUKTION SJAHR 1926/27 I 15 SCHLAGER ^cinhold Schänzel Ruth Weytr Ossi Oswalda Werner Krauss Kui 1 Bois Laura La Plante Lotte Neumann Rudolf Valentine Xenia Desni <$> Lars Hansson Willy Fritsch Jenny Hasselquist Olga Tschechow« Rudolf Förster Conrad Veidt Fioot Gibson Murmuloytupt) IFA-VERIEIHBETRII JE <$> WIR VERMIETEN DIE PRODUKTION jo; IN ZWEI FOLGEN: I. FOLGE ln derHeinuri grins Gräfin Pläilmaii ein Wiedersehn Ossi Osualdd u: Reinhold Schünzci Regisseur: Konstantin D Regisseur: Reinhold Schünze) Voraussichtlich Nosember Voraussichtlich OL Der dule Ruf I & i h a f t s d m o m i l Lotte Neumann Hrgisicui : Pierre Maradon Erscheinungstermin Voraussichtlich Oktober Amcnuitogropf) Die Abenteuer des lonsieurBeautairt Prinzen Achmed Rudolf Valtnlino Oehclmnh'c fincr Serif Ein ptycho anaiyHKhn Film mll Wn nfr Krauh, Ruth Weyer, llka Cu Gn ng Reglueur : G. -

Tim Bergfelder

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION: GERMAN-SPEAKING EMIGRÉS AND BRITISH CINEMA, 1925–50: CULTURAL EXCHANGE, EXILE AND THE BOUNDARIES OF NATIONAL CINEMA Tim Bergfelder Britain can be considered, with the possible exception of the Netherlands, the European country benefiting most from the diaspora of continental film personnel that resulted from the Nazis’ rise to power.1 Kevin Gough- Yates, who pioneered the study of exiles in British cinema, argues that ‘when we consider the films of the 1930s, in which the Europeans played a lesser role, the list of important films is small.’2 Yet the legacy of these Europeans, including their contribution to aesthetic trends, production methods, to professional training and to technological development in the film industry of their host country has been largely forgotten. With the exception of very few individuals, including the screenwriter Emeric Pressburger3 and the producer/director Alexander Korda,4 the history of émigrés in the British film industry from the 1920s through to the end of the Second World War and beyond remains unwritten. This introductory chapter aims to map some of the reasons for this neglect, while also pointing towards the new interventions on the subject that are collected in this anthology. There are complex reasons why the various waves of migrations of German-speaking artists to Britain, from the mid-1920s through to the postwar period, have not received much attention. The first has to do with the dominance of Hollywood in film historical accounts, which has given prominence to the -

Reviews of Three Parent Trap Movies On

Three PARENT TRAP movies are part of the LVCA’s August, 2014 dvd donations to the Hugh Stouppe Memorial Library of the Heritage United Methodist Church of Ligonier, Pennsylvania. Below are Kino Ken’s reviews of those three films. I. THE PARENT TRAP United States 1961 color 129 minutes Walt Disney Productions Producer: George Golitzen 14 of a possible 20 points *** ½ of a possible ***** Key: *indicates outstanding technical achievement or performance (j) designates juvenile performer Points: 1 Direction: David Swift 2 Editing: Philip W. Anderson 1 Cinematography: Lucien Ballard 2 Lighting Special Visual Effects: Ub Iwerks*, Bob Broughton 1 Screenplay: David Swift, based on the novel DAS DOPPELTE LOTTCHEN by Erich Kastner 1 Music: Paul Smith Orchestrations: Franklyn Marks Songs: “Let’s Get Together”, “The Parent Trap” and “For Now, For Always” by Richard and Robert Sherman 2 Art Direction: Carroll Clark, Robert Clatworthy Set Decoration: Hal Gausman, Emile Kuri Costume Design: Bill Thomas Make-up: Pat McNally Animation (opening credits): T. Hee, Bill Justice, Xavier Atencio 1 Sound: Robert Cook (Supervisor), Dean Thomas 1 Cast: Hayley Mills* (j) (Susan Evers / Sharon McKendrick), Maureen O’Hara (Maggie McKendrick, mom), Brian Keith* (Mitch Evers, dad), Susan Henning (j) (Hayley’s double), Charles Ruggles (Charles McKendrick, maternal grandfather), Una Merkel (Verbena, Mitch’s housekeeper / cook), Leo G. Carroll* (Rev. Dr. Mosby), Joanna Barnes* (Vicky Robinson), Cathleen Nesbit (Louise McKendrick, maternal grandmother), Ruth McDevitt (Miss Inch, camp supervisor), Crahan Denton (Hecky, Mitch’s handyman), Linda Watkins (Edna Robinson, Vicky’s mother), Nancy Kulp (Miss Grunecker, Miss Inch’s assistant), Frank De Vol (Mr.