Chapter 11), Making the Events That Occur Within the Time and Space Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proclamation of Domination

FRIDAY January 4, 2019 BARTOW COUNTY’S ONLY DAILY NEWSPAPER 75 CENTS Better Self 101 to prepare attendees for final arrangements BY MARIE NESMITH insurance, what to [choose], who doesn’t let’s bring it to the community for free to likely happen to all of us. I believe that empowered and equip them with the [email protected] have it, etc.?’ Having buried my mother clear any cobwebs and answer any ques- being educated and prepared will help us knowledge needed to succeed in all facets and brother over the past year and [a] half, tions.” through the difficult times when we may in life,” Whitfield said. “No one really Striving to help others be “educated and I know that worrying about money is that Geared only to adults, Better Self 101 not be thinking clearly or not prepared. I wants to have these talks about death but prepared,” Will2Way Foundation Inc. and last burden that one should endure while will take take place from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. will be helping to develop some of the it’s inevitable.What better way than to let Cartersville resident Brad Cowart are join- trying to grieve through the process. at the Cartersville-Bartow County Cham- topics and getting speakers to discuss your loved ones know what you want, ing forces Jan. 12 to present Better Self “After I posed the question, I received ber of Commerce, 122 W. Main St. in them. what you have and talk about it now rather 101: Wills, Insurance, Estate Planning. -

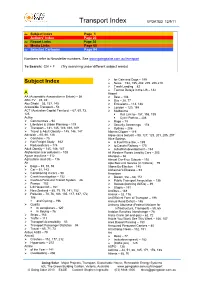

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

Reel Impact: Movies and TV at Changed History

Reel Impact: Movies and TV Õat Changed History - "Õe China Syndrome" Screenwriters and lmmakers often impact society in ways never expected. Frank Deese explores the "The China Syndrome" - the lm that launched Hollywood's social activism - and the eect the lm had on the world's view of nuclear power plants. FRANK DEESE · SEP 24, 2020 Click to tweet this article to your friends and followers! As screenwriters, our work has the capability to reach millions, if not billions - and sometimes what we do actually shifts public opinion, shapes the decision-making of powerful leaders, perpetuates destructive myths, or unexpectedly enlightens the culture. It isn’t always “just entertainment.” Sometimes it’s history. Leo Szilard was irritated. Reading the newspaper in a London hotel on September 12, 1933, the great Hungarian physicist came across an article about a science conference he had not been invited to. Even more irritating was a section about Lord Ernest Rutherford – who famously fathered the “solar system” model of the atom – and his speech where he self-assuredly pronounced: “Anyone who expects a source of power from the transformation of these atoms is talking moonshine.” Stewing over the upper-class British arrogance, Szilard set o on a walk and set his mind to how Rutherford could be proven wrong – how energy might usefully be extracted from the atom. As he crossed the street at Southampton Row near the British Museum, he imagined that if a neutron particle were red at a heavy atomic nucleus, it would render the nucleus unstable, split it apart, release a lot of energy along with more neutrons shooting out to split more atomic nuclei releasing more and more energy and.. -

Pour Nicola Giuliano, Francesca Cima and Medusa Film Present Fabio Conversi Et Jérôme Seydoux Présentent

CRÉATION ORIGINALE : POUR NICOLA GIULIANO, FRANCESCA CIMA AND MEDUSA FILM PRESENT FABIO CONVERSI ET JÉRÔME SEYDOUX PRÉSENTENT ET • MICHAEL HARVEY RACHEL PAUL AND JANE CAINE KEITEL WEISZ DANO FONDA UN FILM DE • A FILM BY PAOLO SORRENTINO DISTRIBUTION • FRENCH DISTRIBUTION & INTERNATIONAL SALES RELATIONS PRESSE • INTERNATIONAL PRESS PATHÉ DISTRIBUTION LE PUBLIC SYSTÈME CINÉMA 2, rue Lamennais Alexis Delage-Toriel, Agnès Leroy, Elsa Leeb 75008 Paris 40, rue Anatole France Tél. : +33 1 71 72 30 00 DURÉE • LENGTH: 1H58 92594 Levallois-Perret Cedex www.pathefilms.com Tél. : +33 1 41 34 21 09 [email protected] À CANNES • IN CANNES INTERNATIONAL SALES [email protected] Boutique Bodyguard Résidences Grand Hôtel - Entrée Ibis • Ibis Entrance www.lepublicsystemecinema.fr 45, la Croisette 45, la Croisette Jardins du Grand Hôtel Appartement 4A/E 4ème étage • 4th floor À CANNES • IN CANNES 06400 Cannes 06400 Cannes 29, rue Bivouac Napoléon Tél. : +33 4 93 99 91 34 Tél. : +33 4 93 68 24 31 06400 Cannes [email protected] Tél. : +33 7 86 23 90 85 Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.pathefilms.com • Material can be downloaded on www.patheinternational.com SYNOPSIS Fred et Mick, deux vieux amis approchant les quatre-vingts ans, Fred and Mick, two old friends approaching their eighties, profitent de leurs vacances dans un bel hôtel au pied des Alpes. are enjoying a vacation in a lovely hotel in the foothills of the Fred, compositeur et chef d’orchestre désormais à la retraite, Alps. Fred, a retired composer and conductor, has no intention n’a aucune intention de revenir à la carrière musicale qu’il a of returning to his music career which he dropped a long time abandonnée depuis longtemps, tandis que Mick, réalisateur, ago, while Mick, a director, is still working, hurrying to finish the travaille toujours, s’empressant de terminer le scénario de son screenplay of his latest film. -

GEMOLOGIST Paradise, Purgatory Or the Pit: What Can DM Managers Learn from EM Managers About Forecasting?

GEMOLOGIST Paradise, purgatory or the pit: what can DM managers learn from EM managers about forecasting? Gary Greenberg, CFA Head of Hermes Emerging Markets Hermes Emerging Markets Newsletter Q2 2017 For professional investors only www.hermes-investment.com 2 GEMOLOGIST PARADISE, PURGATORY OR THE PIT PARADISE, PURGATORY OR THE PIT: WHAT CAN DM MANAGERS LEARN FROM EM MANAGERS ABOUT FORECASTING? The cracks in the global economic WHAT TWO WORLD WARS AND DONALD firmament, while real, are unlikely TRUMP TELL US ABOUT THE MARKET’S to bring the sky crashing down right PREDICTIVE POWERS There’s a widely held belief that the financial markets are prescient, away. Institutions are resilient, and the current consensus view is that the post-US election bull having been strengthened throughout market heralds a bright economic future. But a careful look at the decades of exercising power, but the performance of the German stock market in the 1930s and 1940s should provoke questions about the assumed infallibility of markets problems in the developed world will (see figure 1). foment in the years to come and Figure 1. Blitz then bust: performance of the German stock market, 1930-1950 manifest as significant investment risks. 12 Prices frozen This results in a comparatively upbeat 11 Barbarossa view of emerging markets – however, 10 Battle of Britain Market closed Stalingrad August 1944 if developed markets collapse, 9 Blitzkrieg euphoria 8 all bets are off anyway. Worries that 7 Hitler comes Hitler has gone too far 6 to power 5 4 KEY POINTS 3 Market closed due to credit crisis 2 1931 1941 1937 1947 1932 1935 1942 1933 1945 1939 1950 1936 1934 1943 1938 1949 1930 1946 1944 1948 1940 uuCan financial markets predict the future? Source: “Wealth, War and Wisdom” by Barton Biggs, published by Wiley in 2008 During some pivotal episodes in modern history, investors have collectively made disastrously wrong The rise of the market in the early and mid-1930s made sense – in forecasts. -

March 2020 | Adar-Nisan 5780 | Volume 68 Number 2

March 2020 | Adar-Nisan 5780 | Volume 68 Number 2 THIS PURIM WE'RE GOING INSIDE THIS EDITION: HOW JEWS USE MEMORY AS A TOOL ON PURIM 10 REASONS YOU WON’T WANT TO MISS THIS YEAR’S SPIEL ANNUAL PURIM CARNIVAL HAMANTASCHEN BAKE RenewHow Jews Use Memory Our as a Tool Days on Purim By: Brandon Chiat, Digital Media Manager Jews are a people of memory. In many ways, the past Purim calls to mind the verse from Lamentations: Restore grounds Jewish identity, infusing Jewish life with context, us to You, O Lord, that we may be restored! Renew our purpose, and meaning. days as of old." Jewish memory is why Beth El gathers every year on Rabbi Schwartz explains the bizarrely worded phrase Purim to hear the words of Megillat Esther read aloud in "renew our days as of old" ("chadeish yameinu its entirety. Uniquely, Purim is the only Jewish holiday in k'kedem"): "We have a natural yearning for the past. We which the tradition explicitly commands Jews to listen to look back to happy moments in our life, like sitting next the story in full. to Zadie at Passover Seder, or eating Bubbie's matzah ball soup. These are moments that speak to our identity, "The Megillah is a story of secular, non-religious, our understanding of who we are and where we came unobservant Jews, who find themselves directly from." responsible for the fate of Jewish identity in their part of the diaspora," explained Rabbi Steve Schwartz. "The While it is natural to idealize the past, reflection in powerful message of Purim is that even if you're on the Judaism is more purposeful. -

City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007

The Centrality of Public Consciousness to Improvements in Planning, Architecture and Design P J Keating City Development World 2007 Hilton Hotel, Sydney 5 June 2007 When your conference organisers discussed with me the topic of my address today, they accepted my suggestion that it should be around ‘the centrality of public consciousness in the improvement in planning, architecture and design’. I proposed this for the reason that the only true arbiter of the value of architecture, design and the built environment is the community itself. These questions can never be left solely to the professions, architectural panels or municipal planners. Though much of what is to be built will be expressly decided by the professions, panels of the sort and by planners etc, they will be informed by the prevailing ambience of opinion and culture and by the aspirations of the community they serve. No renowned period of architecture or indeed, cities generally regarded as attractive, ever came to pass without the desire of the respective communities to lift themselves up to something better. And architecture, providing that base requirement of shelter, has often been the modality which has given expression to these new epochs. The Renaissance, with all that it brought forth in architecture, did not occur simply because a clutch of architects gathered to themselves a new regard for Roman and ancient Greek architectural forms. Rather, the inquiry and social flowering which occurred after the long middle ages, gave those architects the authority and the encouragement to create a new classical language in celebration of that renaissance. In other words, it was the aspiration of those peoples who were reaching for something better. -

European Journal of American Studies, 12-4

European journal of American studies 12-4 | 2017 Special Issue: Sound and Vision: Intermediality and American Music Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12383 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12383 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference European journal of American studies, 12-4 | 2017, “Special Issue: Sound and Vision: Intermediality and American Music” [Online], Online since 22 December 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: https:// journals.openedition.org/ejas/12383; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12383 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. European Journal of American studies 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction. Sound and Vision: Intermediality and American Music Frank Mehring and Eric Redling Looking Hip on the Square: Jazz, Cover Art, and the Rise of Creativity Johannes Voelz Jazz Between the Lines: Sound Notation, Dances, and Stereotypes in Hergé’s Early Tintin Comics Lukas Etter The Power of Conformity: Music, Sound, and Vision in Back to the Future Marc Priewe Sound, Vision, and Embodied Performativity in Beyoncé Knowles’ Visual Album Lemonade (2016) Johanna Hartmann “Talking ’Bout My Generation”: Visual History Interviews—A Practitioner’s Report Wolfgang Lorenz European journal of American studies, 12-4 | 2017 2 Introduction. Sound and Vision: Intermediality and American Music Frank Mehring and Eric Redling 1 The medium of music represents a pioneering force of crossing boundaries on cultural, ethnic, racial, and national levels. Critics such as Wilfried Raussert and Reinhold Wagnleitner argue that music more than any other medium travels easily across borders, language barriers, and creates new cultural contact zones (Raussert 1). -

ACTING with an ACCENT

ACTING with an ACCENT ********************* I R I S H (Hyberno English) by DAVID ALAN STERN, PhD Copyright ©1979, 2003 DIALECT ACCENT SPECIALISTS, Inc. P.O. Box 44, Lyndonville, VT 05851 (802) 626-3121 www.LearnAccent.com No part of this manual or the accompanying audio CD may be reproduced or otherwise transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or audio dubbing, without permission in writing from Dialect Accent Specialists, Inc. 2 The ACTING WITH AN ACCENT series New York City Standard British French American Southern Cockney German Texas British North Russian Boston Irish Yiddish "Down East" Scottish Polish "Kennedyesque" Australian Norw./Swed. Chicago Spanish Arabic Mid-West Farm Italian Farsi West Indian/Black African Programs are Also Available for REDUCING Foreign Accents and American Regional Dialects Other Programs Include AMERICAN ACCENTS FOR ENGLISH ACTORS AMERICAN ACCENT FOR CANADIAN ACTORS THE SPEAKER'S VOICE ABOUT THE AUTHOR David Alan Stern received a Ph.D. in Speech from Temple University and served on the faculties of both Wichita State and Penn State before founding Dialect Accent Specialists, Inc. in Hollywood in 1980—working there exclusively as an acting and dialect coach for professional actors. Since 1993, he’s kept his foot in the industry while serving as Professor of Dramatic Arts at his alma mater, the University of Connecticut. Among the many actors he has helped to prepare for stage, television, and film roles are Geena Davis (The Accidental Tourist), Julie Harris (Carried Away), Jennifer Jason Leigh (Fast Times at Ridgemont High), Shelley Long (Outrageous Fortune), Terrence Mann (My Fair Lady), Liam Neeson (Next of Kin), Lynn Regrave (Sweet Sue), Pat Sajak (The Boys in Autumn), Forest Whitaker (Byrd and The Crying Game), and Julia Roberts, Sally Field, Olympia Dukakis, and Daryl Hannah (Steel Magnolias). -

Transgender Woman 'Raped 2,000 Times' in All-Male Prison

A transgender woman was 'raped 2,000 times' in all-male prison Transgender woman 'raped 2,000 times' in all-male prison 'It was hell on earth, it was as if I died and this was my punishment' Will Worley@willrworley Saturday 17 August 2019 09:16 A transgender woman has spoken of the "hell on earth" she suffered after being raped and abused more than 2,000 times in an all-male prison. The woman, known only by her pseudonym, Mary, was imprisoned for four years after stealing a car. She said the abuse began as soon as she entered Brisbane’s notorious Boggo Road Gaol and that her experience was so horrific that she would “rather die than go to prison ever again”. “You are basically set upon with conversations about being protected in return for sex,” Mary told news.com.au. “They are either trying to manipulate you or threaten you into some sort of sexual contact and then, once you perform the requested threat of sex, you are then an easy target as others want their share of sex with you, which is more like rape than consensual sex. “It makes you feel sick but you have no way of defending yourself.” Mary was transferred a number of times, but said Boggo Road was the most violent - and where she suffered the most abuse. After a failed escape, Mary was designated as ‘high-risk’, meaning she had to serve her sentence as a maximum security prisoner alongside the most violent inmates. “I was flogged and bashed to the point where I knew I had to do it in order to survive, but survival was basically for other prisoners’ pleasure,” she said.