Film Policies and Cinema Audiences in Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

Lange Nacht Der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER

31 AUG 13 | 18—2 UHR Lange Nacht der Museen JUNGE WILDE & ALTE MEISTER Museumsinformation Berlin (030) 24 74 98 88 www.lange-nacht-der- M u s e e n . d e präsentiert von OLD MASTERS & YOUNG REBELS Age has occupied man since the beginning of time Cranach’s »Fountain of Youth«. Many other loca- – even if now, with Europe facing an ageing popula- tions display different expression of youth culture tion and youth unemployment, it is more relevant or young artist’s protests: Mail Art in the Akademie than ever. As far back as antiquity we find unsparing der Künste, street art in the Kreuzberg Museum, depictions of old age alongside ideal figures of breakdance in the Deutsches Historisches Museum young athletes. Painters and sculptors in every and graffiti at Lustgarten. epoch have tackled this theme, demonstrating their The new additions to the Long Night programme – virtuosity in the characterisation of the stages of the Skateboard Museum, the Generation 13 muse- life. In history, each new generation has attempted um and the Ramones Museum, dedicated to the to reform society; on a smaller scale, the conflict New York punk band – especially convey the atti- between young and old has always shaped the fami- tude of a generation. There has also been a genera- ly unit – no differently amongst the ruling classes tion change in our team: Wolf Kühnelt, who came up than the common people. with the idea of the Long Night of Museums and The participating museums have creatively picked who kept it vibrant over many years, has passed on up the Long Night theme – in exhibitions, guided the management of the project.We all want to thank tours, films, talks and music. -

Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination : Set Design in 1930S European Cinema 2007

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Tim Bergfelder; Sue Harris; Sarah Street Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination : Set Design in 1930s European Cinema 2007 https://doi.org/10.5117/9789053569801 Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bergfelder, Tim; Harris, Sue; Street, Sarah: Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination : Set Design in 1930s European Cinema. Amsterdam University Press 2007 (Film Culture in Transition). DOI: https://doi.org/10.5117/9789053569801. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons BY-NC 3.0/ This document is made available under a creative commons BY- Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz NC 3.0/ License. For more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ * hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. -

Herbert Windt (1894-1965)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hochschulschriftenserver - Universität Frankfurt am Main Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 4, 2010 / 209 Herbert Windt (1894-1965) Herbert Windt wurde am 15.9.1894 in Senftenberg in der Niederlausitz als Sohn eines Kaufmanns geboren. Seine Familie war sehr musikalisch veranlagt und brachte ihn schon früh zum Klavierspiel und zum Notenstudium. Als junger Mann verließ er die Schule und ging 1910 an das Sternsche Konservatorium, wo er bis zu seiner freiwilligen Meldung zur Teilnahme am Ersten Weltkrieg im Sommer 1914 studierte. 1917 wurde er als Feldwebel bei Verdun so schwer verwundet, dass er zu 75% als kriegsbeschädigt galt und eine Karriere als Dirigent oder Pianist nicht mehr in Frage kam. Windt studierte daher ab 1921 unter dem renommierten Opernkomponisten Franz Schreker an der Hochschule für Musik in Berlin weiter und widmete sich zusehends eigenen Kompositionen, von denen die Oper Andromache (1932) die bedeutendste ist (obgleich sie nur vier Aufführungen erlebte). Windt wandte sich früh den neuen Medien zu und vertonte u.a. einen Flug Hitlers von Ostpreußen zum Niederwald als Funkkantate (1937). Er war seit November 1931 Mitglied der NSDAP und in nationalkonservativen Kreisen so bekannt, dass ihm in diesen eine Vielzahl an Aufträgen in Film, Rundfunk und Fernsehen verschafft wurde. Seine erste abendfüllende Spielfilmmusik zu dem Film MORGENROT (1933), zugleich der erste Film nach der Machtergreifung, sowie weitere Aufträge ließen ihn schnell zum Spezialisten für „heroische“ und „nationale“ Filmmusiken werden (was sich u.a. in einer intensiven Nutzung populärer Wagner-Motive niederschlägt). Seine Musik ist mikro-motivisch orientiert und rhythmisch präzise durchgestaltet, zudem genau auf die Dramaturgie der Filme abgestimmt. -

Der Kinematograph (October 1926)

'^0 GEBÜHR. ALS KOMMANDANT DES UNIENSCHiFFES, HESSEN" ' NEUEN EIKO-MARINE - FILM DER NATION AL-F iLM A.-G. * IN TREUE STARK » . ' Verlorene miiiiiy iPiiiiiiiiiiiiiiKiiiifii.'iii.iiiiiiiiitiiBwiiiMiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiHiiiiiii'iiiiiiiiiiiaimiiiiiiiniii AU CHTE tmmmmmmimmmmmmMmtmmmKmmmmBii Drama in ö Akten aus dem Künstlerleben Regie: Graf Friedr. Carl Perponcßer Hauptdarsteller: Carola Jäger, Eßmi Bessel, Adolf Jeß, Waller Neumann vom Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus Pßofograpßie: Hans Scßeib 'Reic£>ss:en&iert Hersteller : TOSCA-TILM g. m. b. h„ Düsseldorf Alleinvertrieb: Ludwig Rrager 81 Co. am.b.H Berlin SW Aö, Friedricßsiraße lö Telefon: Dönhoff 693, 6Ö2 Telegr.-Adr.: Gegart . REGIE: HENRIK GALEEN c o N n a D V e i z> 1 4CJVES ESTERHAXY WERKEUKUAVSS Er.IT.7A CA T»ORTA SONDBR= VERLEIH BERLIN SW4fl. FRIEDRICHSTP ASSF PA' HASFNHEIDfi 70Ö1-PÄ Ktnrttuttogrnph Rinrmntogrnph DIE UFA'VERLEIH'BETRIEBE BRINGEN ALS ERSTE FOLGE IM PRODUKTION SJAHR 1926/27 I 15 SCHLAGER ^cinhold Schänzel Ruth Weytr Ossi Oswalda Werner Krauss Kui 1 Bois Laura La Plante Lotte Neumann Rudolf Valentine Xenia Desni <$> Lars Hansson Willy Fritsch Jenny Hasselquist Olga Tschechow« Rudolf Förster Conrad Veidt Fioot Gibson Murmuloytupt) IFA-VERIEIHBETRII JE <$> WIR VERMIETEN DIE PRODUKTION jo; IN ZWEI FOLGEN: I. FOLGE ln derHeinuri grins Gräfin Pläilmaii ein Wiedersehn Ossi Osualdd u: Reinhold Schünzci Regisseur: Konstantin D Regisseur: Reinhold Schünze) Voraussichtlich Nosember Voraussichtlich OL Der dule Ruf I & i h a f t s d m o m i l Lotte Neumann Hrgisicui : Pierre Maradon Erscheinungstermin Voraussichtlich Oktober Amcnuitogropf) Die Abenteuer des lonsieurBeautairt Prinzen Achmed Rudolf Valtnlino Oehclmnh'c fincr Serif Ein ptycho anaiyHKhn Film mll Wn nfr Krauh, Ruth Weyer, llka Cu Gn ng Reglueur : G. -

Tim Bergfelder

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION: GERMAN-SPEAKING EMIGRÉS AND BRITISH CINEMA, 1925–50: CULTURAL EXCHANGE, EXILE AND THE BOUNDARIES OF NATIONAL CINEMA Tim Bergfelder Britain can be considered, with the possible exception of the Netherlands, the European country benefiting most from the diaspora of continental film personnel that resulted from the Nazis’ rise to power.1 Kevin Gough- Yates, who pioneered the study of exiles in British cinema, argues that ‘when we consider the films of the 1930s, in which the Europeans played a lesser role, the list of important films is small.’2 Yet the legacy of these Europeans, including their contribution to aesthetic trends, production methods, to professional training and to technological development in the film industry of their host country has been largely forgotten. With the exception of very few individuals, including the screenwriter Emeric Pressburger3 and the producer/director Alexander Korda,4 the history of émigrés in the British film industry from the 1920s through to the end of the Second World War and beyond remains unwritten. This introductory chapter aims to map some of the reasons for this neglect, while also pointing towards the new interventions on the subject that are collected in this anthology. There are complex reasons why the various waves of migrations of German-speaking artists to Britain, from the mid-1920s through to the postwar period, have not received much attention. The first has to do with the dominance of Hollywood in film historical accounts, which has given prominence to the -

Muchachas-De-Uniforme.Pdf

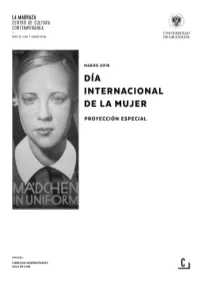

Sábado 9 marzo 20 h. DÍA INTERNACIONAL DE LA MUJER Sala Máxima del Espacio V Centenario Proyección Especial (Antigua Facultad de Medicina en Av. de Madrid) Entrada libre hasta completar aforo MUCHACHAS DE UNIFORME (1931) Alemania 83 min. Título Orig.- Mädchen in Uniform. Director.- Leontine Sagan & Carl Froelich. Argumento.- Las obras teatrales “Ritter Nérestan” (“Caballero Nérestan”, 1930) y “Gestern und Heuten” (“Ayer y hoy”, 1931) de Christa Winsloe. Guión.- Christa Winsloe y Friedrich Dammann. Fotografía.- Reimar Kuntze y Franz Weihmayr (1.20:1 – B/N). Montaje.- Oswald Hafenrichter. Música.- Hanson Milde-Meissner. Productor.- Carl Froelich y Friedrich Pflughaupt. Producción.- Deutsche Film- Gemeinschaft / Bild und Ton GmbH. Intérpretes.- Hertha Thiele (Manuela von Meinhardis), Dorothea Wieck (señorita von Bernburg), Hedwig Schlichter (señorita von Kesten), Ellen Schwanneke (Ilse von Westhagen), Emilia Unda (la directora), Erika Biebrach (Lilli von Kattner), Lene Berdoit (señorita von Gaerschner), Margory Bodker (señorita Evans), Erika Mann (señorita von Atems), Gertrud de Lalsky (tía de Manuela). Versión original en alemán con subtítulos en español Película nº 1 de la filmografía de Leontine Sagan (de 3 como directora) Premio del Público en el Festival de Venecia Música de sala: Berlin Cabaret songs Ute Lemper 3 En los primeros años de la historia cinematográfica alemana, la atracción entre mujeres en las películas mudas aparece sólo someramente, al margen y en la forma de Hosenrollen (muje- res con pantalones).1 En un momento de necesidad -

The National Film Preserve Ltd. Presents the This Festival Is Dedicated To

THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. PRESENTS THE THIS FESTIVAL IS DEDICATED TO Sam Shepard 1943–2017 THE NATIONAL FILM PRESERVE LTD. PRESENTS THE Julie Huntsinger | Directors Tom Luddy Joshua Oppenheimer | Guest Director Mara Fortes | Curator Kirsten Laursen | Chief of Staff Brandt Garber | Production Manager Karen Schwartzman | SVP, Partnerships Erika Moss Gordon | VP, Filmanthropy & Education Melissa DeMicco | Development Manager Joanna Lyons | Events Manager Bärbel Hacke | Hosts Manager Shannon Mitchell | VP, Publicity Justin Bradshaw | Media Manager Lily Coyle | Assistant to the Directors Marc McDonald | Theater Operations Manager Lucy Lerner | SHOWCorps Manager Erica Gioga | Housing/Travel Manager Chapin Cutler | Technical Director Ross Krantz | Technical Wizard Barbara Grassia | Projection and Inspection Annette Insdorf | Moderator Paolo Cherchi Usai | Resident Curators Mark Danner Pierre Rissient Peter Sellars Publications Editor Jason Silverman (JS) Chief Writer Larry Gross (LG) Prized Program Contributors Fiona Armour (FA), Sheerly Avni (SA), Meredith Brody (MB), Paolo Cherchi Usai (PCU), Mark Danner (MD), Mara Fortes (MF), Scott Foundas (SF), Gary Giddins (GG), Leonard Maltin (LM), Errol Morris (EM), Joshua Oppenheimer (JO), Peter Sellars (PS), Milos Stehlik (MS), David Thomson (DT), Alice Waters (AW) Tribute Curator Short Films Curators Student Prints Curator Chris Robinson Barry Jenkins Gregory Nava Nicholas O’Neill 1 Guest Director Sponsored by FilmStruck The National Film Preserve, Ltd. Each year, Telluride’s Guest Director serves as a key collaborator in the A Colorado 501(c)(3) nonprofit, tax-exempt educational corporation Festival’s programming decisions, bringing new ideas and overlooked films. Past Guest Directors include Laurie Anderson, Geoff Dyer, Buck Henry, Founded in 1974 by James Card, Tom Luddy and Bill & Stella Pence Guy Maddin, Michael Ondaatje, Alexander Payne, B. -

Klassiker Der Deutschen Filme

Klassiker der deutschen Filme Die Konferenz der Tiere (1969) ..................................................................................................3 Zwei blaue Vergißmeinnicht (1963)............................................................................................4 So liebt und küsst man in Tirol (1961) ........................................................................................5 Am Sonntag will mein Süsser… (1961) ......................................................................................5 Allotria in Zell am See (1963).....................................................................................................6 Freddy und das Lied der Südsee (1962).......................................................................................7 Lady Windermeres Fächer (1935)...............................................................................................7 Fridericus - Der Alte Fritz (1963)................................................................................................8 Paradies Paradies der Junggesellen (1939) ..................................................................................9 Der Kaiser von Kalifornien (1935/36).........................................................................................9 Amphitryon (1935) ...................................................................................................................10 Der Jugendrichter (1959) ..........................................................................................................11 -

Copyright by Christelle Georgette Le Faucheur 2012

Copyright by Christelle Georgette Le Faucheur 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Christelle Georgette Le Faucheur Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Defining Nazi Film: The Film Press and the German Cinematic Project, 1933-1945 Committee: David Crew, Supervisor Sabine Hake, Co-Supervisor Judith Coffin Joan Neuberger Janet Staiger Defining Nazi Film: The Film Press and the German Cinematic Project, 1933-1945 by Christelle Georgette Le Faucheur, Magister Artium Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 Acknowledgements Though the writing of the dissertation is often a solitary endeavor, I could not have completed it without the support of a number of institutions and individuals. I am grateful to the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin, for its consistent support of my graduate studies. Years of Teaching Assistantships followed by Assistant Instructor positions have allowed me to remain financially afloat, a vital condition for the completion of any dissertation. Grants from the Dora Bonham Memorial Fund and the Centennial Graduate Student Support Fund enabled me to travel to conferences and present the preliminary results of my work, leading to fruitful discussions and great improvements. The Continuing Fellowship supported a year of dissertation writing. Without the help of Marilyn Lehman, Graduate Coordinator, most of this would not have been possible and I am grateful for her help. I must also thank the German Academic Exchange Service, DAAD, for granting me two extensive scholarships which allowed me to travel to Germany. -

January 26, 2016 (XXXII:1) Georg Wilhelm Pabst, PANDORA’S BOX/DIE BÜCHSE DER PANDORA (1929, 133 Min)

January 26, 2016 (XXXII:1) Georg Wilhelm Pabst, PANDORA’S BOX/DIE BÜCHSE DER PANDORA (1929, 133 min) Louise Brooks ..Lulu Fritz Kortner..Dr. Peter Schön Francis Lederer....Alwa Schön Carl Goetz....Schigolch Krafft-Raschig....Rodrigo Quast Alice Roberts....Countess Anna Geschwitz Gustav Diessl....Jack the Ripper Michael von Newlinsky....Marquis Casti-Piani Directed by Georg Wilhelm Pabst Written by Joseph Fleisler, Georg Wilhelm Pabst, Ladislaus Vajda, based on Frank Wedekind’s plays Der Erdgeist and Die Büchse der Pandora) Produced by Seymour Nebenzal Cinematography by Günther Krampf Queens, but she hated Hollywood and, after working with Pabst, pretty much let her career lapse rather than go back there. Her last GEORG WILHELM PABST (27 August 1885, Raudnitz, film was a small part in Overland Stage Raiders 1938, which featured Austria —29 May 1967, Vienna) directed 39 films. The first was the still-unknown John Wayne (he would become a star the following Der Schatz 1923 (The Treasure), the last Durch die Wälder 1956 year with Stagecoach). During the 30s she supported herself working (Through the Forests and Through the Trees). Some of the others as a clerk in a New York department store, turning occasional tricks, were Rosen für Bettina 1956 (Ballerina), Der Letzte Akt 1955 dancing, and taking a few small film roles. In her later years, she was (Hitler: The Last Ten Days), La Conciencia acusa 1952, (Voice supported by one of her former lovers. Some of the films on which of Silence), Der Prozeß 1948 (The Trial), Paracelsus 1943, her reputation rests are Prix de beauté 1930, Das Tagebuch einer Jeunes filles en détresse 1939, Mademoiselle Docteur 1936, Verlorenen, 1929, The Canary Murder Case 1929 (she was the canary (Street of Shadows), White Hunter 1936, Don Quixote 1933, and insisted that her costume have a removable tail so she could sit Kameradschaft 1931 (Comradeship), Die 3groschenoper 1931 down between takes), Beggars of Life 1928, A Girl in Every Port 1928 (The Threepenny Opera), Die Weiße Hülle vom Piz Palü 1929 and It's the Old Army Game 1926 . -

The Radical Progress of Queer Visibility in Weimar Film and the Inevitable Backlash That Followed

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 2019 A Glimpse of Casual Queerness: The Radical Progress of Queer Visibility in Weimar Film and the Inevitable Backlash That Followed Claire Colburn Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Colburn, Claire, "A Glimpse of Casual Queerness: The Radical Progress of Queer Visibility in Weimar Film and the Inevitable Backlash That Followed" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 469. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/469 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Glimpse of Casual Queerness: The Radical Progress of Queer Visibility in Weimar Film and the Inevitable Backlash That Followed A Thesis Presented to the Department of English College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Claire Colburn May 10, 2019 Modern representations of Germany’s Jazz Age, such as the popular television series Babylon Berlin (dir. Tom Tykwer, 2017-2019), tend to characterize the interwar period as a chaotic expression of post-World War I anxiety. In retrospect, it can be temptingly easy to credit the changing political landscape and liberalization of German society between 1918 and 1933 as a brief but inherently doomed moment of progressivism that necessarily would give way to a strident, reactionary backlash.