TCHAIKOVSKY FREDDY KEMPF Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

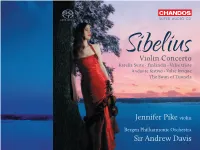

Jennifer Pike Violin Sir Andrew Davis

SUPER AUDIO CD SibeliusViolin Concerto Karelia Suite • Finlandia • Valse triste Andante festivo • Valse lyrique The Swan of Tuonela Jennifer Pike violin Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis AKG Images, London Images, AKG Jean Sibelius, at his house, Ainola, in Järvenpää, near Helsinki, 1907 Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1957) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 47* 31:55 in D minor • in d-Moll • en ré mineur 1 I Allegro moderato – [Cadenza] – Tempo I – Molto moderato e tranquillo – Largamente – Allegro molto – Moderato assai – [Cadenza] – Allegro moderato – Allegro molto vivace 15:46 2 II Adagio di molto 8:16 3 III Allegro, ma non tanto 7:44 Karelia Suite, Op. 11 15:51 for Orchestra from music to historical tableaux on the history of Karelia 4 I Intermezzo. Moderato – Meno – Più moderato 4:03 5 II Ballade. Tempo di menuetto – Un poco più lento 7:13 Hege Sellevåg cor anglais 6 III Alla marcia. Moderato – Poco largamente 4:27 3 7 The Swan of Tuonela, Op. 22 No. 2 8:16 (Tuonelan joutsen) from the Lemminkäinen Legends after the Finnish national epic Kalevala compiled by Elias Lönnrot (1802 – 1884) Hege Sellevåg cor anglais Jonathan Aasgaard cello Andante molto sostenuto – Meno moderato – Tempo I 8 Valse lyrique, Op. 96a 4:09 Work originally for solo piano, ‘Syringa’ (Lilac), orchestrated by the composer Poco moderato – Stretto e poco a poco più – Tempo I 9 Valse triste, Op. 44 No. 1 5:03 from the incidental music to the drama Kuolema (Death) by Arvid Järnefelt (1861 – 1932) Lento – Poco risoluto – Più risoluto e mosso – Stretto – Lento assai 4 10 Andante festivo, JS 34b 4:06 Work originally for string quartet, arranged by the composer for strings and timpani ad libitum 11 Finlandia, Op. -

PROMS 2018 Page 1 of 7

PROMS 2018 Page 1 of 7 Prom 1: First Night of the Proms Sam Walton percussion Piano Concerto No 1 in G minor (20 mins) 20:15 Friday 13 July 2018 ON TV Martin James Bartlett piano Royal Albert Hall Freddy Kempf piano Morfydd Llwyn Owen Lara Melda piano Nocturne (15 mins) Ralph Vaughan Williams Lauren Zhang piano Toward the Unknown Region (13 mins) BBC Concert Orchestra Robert Schumann Andrew Gourlay conductor Symphony No 4 in D minor (original 1841 version) (28 mins) Gustav Holst The Planets (52 mins) Bertrand Chamayou piano Proms at … Cadogan Hall 1 BBC National Orchestra of Wales Anna Meredith 13:00 Monday 16 July 2018 Thomas Søndergård conductor 59 Productions Cadogan Hall, London Five Telegrams (22 mins) BBC co-commission with 14–18 NOW and Edinburgh Caroline Shaw Proms at … The Roundhouse International Festival: world première Second Essay: Echo (15 mins) 15:00 Saturday 21 July 2018 Third Essay: Ruby Roundhouse, Camden National Youth Choir of Great Britain BBC Symphony Chorus Robert Schumann Charles Ives BBC Proms Youth Ensemble Piano Quintet in E flat major, Op 44 (30 mins) The Unanswered Question (6 mins) BBC Symphony Orchestra Sakari Oramo conductor Calidore String Quartet ensemble Georg Friedrich Haas Javier Perianes piano the last minutes of inhumanity (5 mins) world première Prom 2: Mozart, Ravel and Fauré 19:30 Saturday 14 July 2018 Prom 4: Shostakovich’s ‘Leningrad’ Hannah Kendall Royal Albert Hall Verdala (5 mins) Symphony world première 19:30 Monday 16 July 2018 Gabriel Fauré Royal Albert Hall Pavane (choral version) (5 -

Ne W Burysprin G Fe Stival

www.newburyspringfestival.org.uk 34th international newburyspringfestival 12 – 26 may 2012 Royal Philharmonic Sat Welcome Orchestra 12th This year, when London hosts the Owain Arwel Hughes conductor Olympic Games and welcomes the Freddy Kempf piano world’s finest young athletes to the Walton Crown Imperial capital, I am delighted that we will Beethoven Piano Concerto No 5 “Emperor” welcome to Newbury so many Brahms Symphony No 4 outstanding musicians from around the world. Among them are important young musicians who are already building A welcome return to the Festival by the RPO, and conductor careers in Britain: this year’s John Lewis Young Stars , Owain Arwel Hughes in his 70th birthday year, in a and our Festival artist Johan Andersson, one of the world’s celebratory concert that opens with Walton’s Crown Imperial in honour of HM The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee. finest young painters, who is also based in this country. The current season sees dynamic British pianist Freddy This national celebration of international youthful excellence Kempf perform the complete cycle of piano concertos in sport and culture is balanced by another important by his favourite composer, Beethoven, in many of the UK’s national celebration: the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, an most important venues and tonight he joins the orchestra opportunity to honour a monarch who has been on the for the majestic Piano Concerto No 5, popularly known as throne for sixty years and who represents all that is constant the “Emperor Concerto”. The concert ends with Brahms’ and traditional in our country. You will find in this year’s final and best loved Symphony No 4. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Westminster City Council's out and About Free Ticket Scheme Autumn

Westminster City Council’s Out and About free ticket scheme Autumn 2017 programme September Events Wednesday 13th September, 6pm – 7pm at Westminster Music Library Songs from my land and beyond A recital of songs from around the world by Argentinian soprano Susana Gilardoni Mirski accompanied by pianist Benedict Lewis-Smith Saturday 16th September at City of Westminster Archives Centre Open House weekend – no need to book Swinging Sixties themed open house day with tours of the search room, conservation and strong room for the public, spiced up with a small archive display called ‘Carnaby Street to King’s Road’. Tours will take place at 11 am, 12 noon, 1 pm, 2 pm, 3 pm and 4 pm, booking not required. Tuesday 19th September, 1pm at Wigmore Hall Benjamin Baker, violin Daniel Lebhardt, piano In 2016 Benjamin Baker won 1st Prize at the Young Concert Artists auditions in New York. The 2016/17 season saw him make his debuts with the Royal Philharmonic and Auckland Philharmonia Orchestras. Daniel Lebhardt won 1st Prize at the Young Concert Artists auditions in both Paris and New York in 2015. In 2016 he won the Most Promising Pianist prize at the Sydney International Piano Competition. Janacek: Violin Sonata Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 9 in A major Op. 47 ‘Kreutzer’ Saturday 30th September, 10am – 1pm at Westminster Music Library A Feast of Folk Songs: A Choral Workshop Musical Director Ruairi Glasheen will lead this singing workshop as part of this year’s Silver Sunday celebrations. Please note this event will take place on the Saturday! October Events Tuesday 3rd October, 1pm at Wigmore Hall Peter Moore, trombone Richard Uttley, piano In 2008, at the age of 12, Peter Moore became the youngest ever winner of the BBC Young Musician Competition. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE www.kingslynnfestival.org.uk/press February 9 2009 Exciting variety for 2009 programme An exciting variety of entertainment, ranging from a top German orchestra to The Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain and Classic Brit award winners Blake, will give this summer’s King’s Lynn Festival especially broad appeal. With favourites from the classical music world, jazz, folk and top-name writers, artistic director Ambrose Miller said the line-up offered “something for everyone”. “By widening the appeal of the event we are not compromising our high standards but are continuing our tradition of excellence in all that we do,” he said. Classical music remains the cornerstone of the 59th Festival and includes a visit by Berlin Symphoniker, a leading German orchestra. Classic BRIT 2008 Album of the Year award winners Blake, four classically-trained singers who have successfully bridged the gap between pop and opera, will make their first appearance in the area. Their meteoric rise to stardom has included singing at the Queen’s 80th birthday party at Windsor Castle, and their version of Swing Low became the official anthem of the England team in the 2007 Rugby World Cup. The Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain has proved a sensation, selling out where ever they appear. Their first gig in 1985 was intended as a one-off but they were soon touring the world and have been described as “a musical phenomenon”. The Mike Piggott Hot Club Trio with perform their tribute to the legendary jazz violinist Stephane Grappelli, and folk music by Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick. -

Past Concerts - 1990/2016 2015/16

CONCERTS 1990/2015 1 PAST CONCERTS - 1990/2016 2015/16 Mote Hall / 10 October 2015 Taek-Gi Lee (piano) MSO / Wright Khachaturian - Three Dances from “Gayane” Rachmaninov - Piano Concerto 3 Rimsky-Korsakov - Scheherazade Mote Hall / 28 November 2015 Laura van der Heijden (cello) MSO / Wright Richard Strauss - Don Juan Walton - Cello Concerto Roussel - The Spider’s Banquet Elgar - In the South Mote Hall / 30 January 2016 Martin James Bartlett (piano) MSO / Wright Nielsen - Overture, Helios Mozart - Piano Concerto 12, K.414 Dvorak - Symphony 7 Mote Hall / 19 March 2016 Paul Beniston (trumpet) MSO / Wright Barber - Adagio for strings Arutiunian - Trumpet Concerto Mahler - Symphony 9 Mote Hall / 21 May 2016 Callum Smart (violin) MSO / Wright Borodin - Overture, Prince Igor Prokofiev - Violin Concerto 2 Tchaikovsky - Symphony 5 CONCERTS 1990/2015 2 2014/15 2013/14 Mote Hall / 11 October 2014 Mote Hall / 12 October 2013 Tae-Hyung Kim (piano) Laura van der Heijden (cello) MSO / Wright MSO / Wright Wagner – Overture Tannhäuser Britten – Four Sea Interludes from “Peter Beethoven – Piano Concerto 5 Grimes” “Emperor” Elgar – Cello Concerto Tchaikovsky – Symphony 1 “Winter Rachmaninov – Symphony 3 Daydreams” Mote Hall / 30 November 2013 Mote Hall / 29 November 2014 Tom Bettley (horn) Giovanni Guzzo (violin) MSO / Wright MSO / Wright Berlioz – Overture, Roman Carnival Copland – Appalachian Spring Glière – Horn Concerto Brahms – Violin Concerto Richard Strauss – Death and Vaughan Williams – Symphony 4 Transfiguration Stravinsky – Suite, The Firebird -

"Classical Piano" Competition in Dubai 4Th Round

29 Mahler - Symphony No.1 "Titan" Aram Khachaturian Concert Hall, Yerevan, Armenia Sep 2021 Orchestra Armenian State Symphony Orchestra Program Gustav Mahler - Symphony No.1 "Titan" 56' 29 Armenia International Music Festival Aram Khachaturian Concert Hall, Yerevan, Armenia Sep 2021 Orchestra Armenian State Symphony Orchestra Soloist Marc Bouchkov / violin Program Sergei Prokofiev - March from "The Love for Three Oranges" Sergei Prokofiev - Violin Concerto No.1 Modest Mussorgsky/Maurice Ravel - Pictures at an Exhibition 29 Concert with Mikhail Pletnev Aram Khachaturian Concert Hall, Yerevan, Armenia Oct 2021 Orchestra Armenian State Symphony Orchestra Soloist Mikhail Pletnev / piano Program Edward Grieg - Excerpts from "Peer Gynt" Suites 18' Alexey Shor - Piano Concerto "From My Bookshelf" 42' 14 Concert with the Elbląska Orkiestra Kameralna Nov 2021 ZPSM, Elbląg, Poland Orchestra Elbl?ska Orkiestra Kameralna Soloist Karolina Nowotczy?ska / violin Program Edward Grieg - Holberg Suite, Op.40 20’ Edward Mirzoyan - Lyric Poem “Shushanik” 6’ Ludwig van Beethoven - Violin Concerto in D major, Op.61 40’ (String Version) 14 Concert with Russian National Orchestra Prokofiev Concert Hall, Chelyabinsk, Russia Nov 2021 Orchestra Russian National Orchestra Soloist Sofia Yakovenko / violin Program P. Tchaikovsky - Violin Concerto L. W. Beethoven - Symphony No. 4 15 Tariverdiev Anniversary Concert Aram Khachaturian Concert Hall, Yerevan, Armenia Nov 2021 Orchestra Armenian State Symphony Orchestra Soloist Haik Kazazyan / violin Program TBA 22 Pre Tour -

Ascending Centenary

Programme notesBristol Beacon & Bristol Ensemble present THE LARK ASCENDING CENTENARY Programme notes Bristol Beacon and Bristol Ensemble Present The Lark Ascending Centenary Concert Tuesday 15 December 2020 at 7.30pm Filmed at Shirehampton Public Hall Programme Jennifer Pike violin Roger Huckle violin Simon Kodurand violin Helen Reid piano Marcus Farnsworth baritone David Ogden conductor Bristol Ensemble Members of Exultate Singers Dr Jonathan James compère Vaughan Williams Fantasia on Christmas Carols Vaughan Williams The Lark Ascending (arr. for violin and piano) J S Bach Concerto for Two Violins in D minor BWV 1043 Parry Choral song “Jerusalem” Programme notes Fantasia on Christmas Carols Ralph Vaughan Williams This single-movement work for baritone, chorus and orchestra consists of a selection of English folk carols collected in southern England by Vaughan Williams and his friend Cecil Sharp to whom the work is dedicated. From Herefordshire ‘There is a fountain’ and The Truth sent from above; from Somerset Come all you worthy gentlemen and from Sussex On Christmas night all Christians sing. These carols are interposed with brief orchestral quotations from other carols, such as The First Nowell. The piece was first performed on 12 September 1912 at the Three Choirs Festival in Hereford Cathedral, conducted by the composer. The Lark Ascending Ralph Vaughan Williams In the composition of this iconic, 100-year-old work, Ralph From its opening bars, this composition has a magical Vaughan Williams sought an escape from the onset and quality to it. The orchestra plays a soft and peaceful effects of war. His knowledge of violin technique, a love of introduction, then quietly sustains a chord. -

Concert Series at Vinehall

HEATH STRING QUARTET ALEXANDER CHAUSHIAN (Cello) VINEHALL INTERNATIONAL CONCERTS BOOKING FORM ALICE NEARY (Cello) YEVGENY SUDBIN (Piano) Please complete as required. Bookings can be made by post, phone or Welcome to International Classical email during the season. Concerts at Vinehall Saturday November 28th 2020 at 7.30 p.m. Sunday February 7th 2021 at 3.00 p.m. A FULL SEASON TICKET provides one seat at each of the seven The Vinehall Concert Series, celebrating its 32nd season, concerts. The SIX CONCERT OPTION and the FIVE CONCERT continues to bring the best of both British and international OPTION allow you to select six or five different concerts of your musicians to East Sussex. Performances take place in a purpose-built 250 seat theatre with superb piano and intimate choice. SINGLE TICKETS may also be booked for all concerts. acoustic which is ideal for chamber music. Please indicate your choice on the form overleaf. Complimentary SACCONI STRING QUARTET refreshments are served at each concert. SCHUBERT & CO MICHAEL COLLINS (Clarinet) We regret that we cannot exchange or refund tickets unless a Director and Piano: SHOLTO KYNOCH Saturday November 7th 2020 at 7.30 p.m. Alexander Chaushian ‘…a force to be reckoned with…’ The Guardian concert is sold out. As concerts are booked many months on “Great power and sweetness ... intimate closeness.” Spectator Programme advance there may be changes in advertised details. We are able to Saturday October 3rd 2020 at 7.30 p.m. offer assistance with transport throughout the area and have easy Programme Bach Suite no 1 for Cello in G major Sponsored anonymously Weber Clarinet Quintet in B flat major Op. -

Russia's Oldest and Most Revered Symphony Orchestra Play At

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE USE Russia’s oldest and most revered symphony orchestra play at Edinburgh’s iconic Usher Hall St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra with Yuri Temirkanov and Freddy Kempf Sunday Classics at the Usher hall, Edinburgh 3:00pm, Sunday 27 January 2019 Rachmaninov - Piano Concerto No. 2 Mahler - Symphony No. 4 Images available to download here The historic and prestigious St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra will take to the stage of Edinburgh’s Usher hall in the first Sunday Classics concert of 2019. The legendary orchestra will be led by their longstanding Artistic Director and Chief Conductor Yuri Temirkanov. They will also be joined by leading British pianist Freddy Kempf for Rachmaninov’s second piano concerto. Often described as the greatest piano concerto ever written and adored by millions as the soundtrack to cinematic classic Brief Encounter, Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto is musical romance at its finest. Usher Hall audiences will be swept up in the piece’s gorgeous melodies, its heart-on-sleeve emotion, its dazzling orchestral colours. Few performances of this passionate music can be as authentic as one from the St Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra – dubbed the crowning glory of Russian culture, and Russia’s oldest and most revered symphony orchestra. With its roots dating back to 1882, it has an illustrious history and has been a constant through revolution and war in Russia. In 1934 it was awarded the title Honoured Ensemble of Russia, the first of the century, and later developed a close relationship with Shostakovich himself, performing five of the great Russian composer’s symphonies for the first time. -

Oxford Piano Festival 1 - 9 August 2020

Alfred Brendel KBE Patron Oxford Sir András Schiff President Philharmonic Marios Papadopoulos MBE Artistic Director Orchestra Oxford Piano Festival 1 - 9 August 2020 Pianist MAGAZINE Media partner REFLECTIONS ON THE 2019 OXforD PIANO FESTIVAL WELCOME from FESTIVAL ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MARIOS PapaDopoULOS ‘So great to come across and performance of two titled sonatas and the Diabelli Variations later that evening – a fitting exchange ideas with so many way to mark 250 years since the birth of the legendary pianists.’ composer who transformed the piano sonata. As well as young talent, we have some ‘Was a blast to be back! I’m highly distinguished guests at this year’s festival. Nelson Freire, one the finest Brahms enjoying so much to be a part of players alive, makes his Festival debut in a the Oxford family and I would performance of Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 2 with the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra, love to come back next year!’ which it is my privilege and pleasure to conduct. Elisabeth Leonskaja, a towering Last year in this introduction, I wrote pianist and prolific recording artist, also ‘Every performance I played, I had about the apparently endless, universal makes her Festival debut in the opening a lot of useful feedback from the capabilities of the piano – the instrument’s concert on 1 August. A champion of unusual status as both a solo orator and a congenial and contemporary repertoire, Alain Lefèvre professors, audiences and observers.’ conversationalist, a vessel for self-absorbed also joins us for the first time. introspection and unbounded, triumphant communication. I am particularly proud that the Festival has a habit of cultivating long-term friendships.