Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

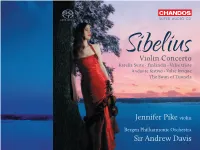

Jennifer Pike Violin Sir Andrew Davis

SUPER AUDIO CD SibeliusViolin Concerto Karelia Suite • Finlandia • Valse triste Andante festivo • Valse lyrique The Swan of Tuonela Jennifer Pike violin Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis AKG Images, London Images, AKG Jean Sibelius, at his house, Ainola, in Järvenpää, near Helsinki, 1907 Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1957) Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 47* 31:55 in D minor • in d-Moll • en ré mineur 1 I Allegro moderato – [Cadenza] – Tempo I – Molto moderato e tranquillo – Largamente – Allegro molto – Moderato assai – [Cadenza] – Allegro moderato – Allegro molto vivace 15:46 2 II Adagio di molto 8:16 3 III Allegro, ma non tanto 7:44 Karelia Suite, Op. 11 15:51 for Orchestra from music to historical tableaux on the history of Karelia 4 I Intermezzo. Moderato – Meno – Più moderato 4:03 5 II Ballade. Tempo di menuetto – Un poco più lento 7:13 Hege Sellevåg cor anglais 6 III Alla marcia. Moderato – Poco largamente 4:27 3 7 The Swan of Tuonela, Op. 22 No. 2 8:16 (Tuonelan joutsen) from the Lemminkäinen Legends after the Finnish national epic Kalevala compiled by Elias Lönnrot (1802 – 1884) Hege Sellevåg cor anglais Jonathan Aasgaard cello Andante molto sostenuto – Meno moderato – Tempo I 8 Valse lyrique, Op. 96a 4:09 Work originally for solo piano, ‘Syringa’ (Lilac), orchestrated by the composer Poco moderato – Stretto e poco a poco più – Tempo I 9 Valse triste, Op. 44 No. 1 5:03 from the incidental music to the drama Kuolema (Death) by Arvid Järnefelt (1861 – 1932) Lento – Poco risoluto – Più risoluto e mosso – Stretto – Lento assai 4 10 Andante festivo, JS 34b 4:06 Work originally for string quartet, arranged by the composer for strings and timpani ad libitum 11 Finlandia, Op. -

PROMS 2018 Page 1 of 7

PROMS 2018 Page 1 of 7 Prom 1: First Night of the Proms Sam Walton percussion Piano Concerto No 1 in G minor (20 mins) 20:15 Friday 13 July 2018 ON TV Martin James Bartlett piano Royal Albert Hall Freddy Kempf piano Morfydd Llwyn Owen Lara Melda piano Nocturne (15 mins) Ralph Vaughan Williams Lauren Zhang piano Toward the Unknown Region (13 mins) BBC Concert Orchestra Robert Schumann Andrew Gourlay conductor Symphony No 4 in D minor (original 1841 version) (28 mins) Gustav Holst The Planets (52 mins) Bertrand Chamayou piano Proms at … Cadogan Hall 1 BBC National Orchestra of Wales Anna Meredith 13:00 Monday 16 July 2018 Thomas Søndergård conductor 59 Productions Cadogan Hall, London Five Telegrams (22 mins) BBC co-commission with 14–18 NOW and Edinburgh Caroline Shaw Proms at … The Roundhouse International Festival: world première Second Essay: Echo (15 mins) 15:00 Saturday 21 July 2018 Third Essay: Ruby Roundhouse, Camden National Youth Choir of Great Britain BBC Symphony Chorus Robert Schumann Charles Ives BBC Proms Youth Ensemble Piano Quintet in E flat major, Op 44 (30 mins) The Unanswered Question (6 mins) BBC Symphony Orchestra Sakari Oramo conductor Calidore String Quartet ensemble Georg Friedrich Haas Javier Perianes piano the last minutes of inhumanity (5 mins) world première Prom 2: Mozart, Ravel and Fauré 19:30 Saturday 14 July 2018 Prom 4: Shostakovich’s ‘Leningrad’ Hannah Kendall Royal Albert Hall Verdala (5 mins) Symphony world première 19:30 Monday 16 July 2018 Gabriel Fauré Royal Albert Hall Pavane (choral version) (5 -

Ne W Burysprin G Fe Stival

www.newburyspringfestival.org.uk 34th international newburyspringfestival 12 – 26 may 2012 Royal Philharmonic Sat Welcome Orchestra 12th This year, when London hosts the Owain Arwel Hughes conductor Olympic Games and welcomes the Freddy Kempf piano world’s finest young athletes to the Walton Crown Imperial capital, I am delighted that we will Beethoven Piano Concerto No 5 “Emperor” welcome to Newbury so many Brahms Symphony No 4 outstanding musicians from around the world. Among them are important young musicians who are already building A welcome return to the Festival by the RPO, and conductor careers in Britain: this year’s John Lewis Young Stars , Owain Arwel Hughes in his 70th birthday year, in a and our Festival artist Johan Andersson, one of the world’s celebratory concert that opens with Walton’s Crown Imperial in honour of HM The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee. finest young painters, who is also based in this country. The current season sees dynamic British pianist Freddy This national celebration of international youthful excellence Kempf perform the complete cycle of piano concertos in sport and culture is balanced by another important by his favourite composer, Beethoven, in many of the UK’s national celebration: the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, an most important venues and tonight he joins the orchestra opportunity to honour a monarch who has been on the for the majestic Piano Concerto No 5, popularly known as throne for sixty years and who represents all that is constant the “Emperor Concerto”. The concert ends with Brahms’ and traditional in our country. You will find in this year’s final and best loved Symphony No 4. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 An Annotated Catalogue of the Major Piano Works of Sergei Rachmaninoff Angela Glover Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC AN ANNOTATED CATALOGUE OF THE MAJOR PIANO WORKS OF SERGEI RACHMANINOFF By ANGELA GLOVER A Treatise submitted to the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the treatise of Angela Glover defended on April 8, 2003. ___________________________________ Professor James Streem Professor Directing Treatise ___________________________________ Professor Janice Harsanyi Outside Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Carolyn Bridger Committee Member ___________________________________ Professor Thomas Wright Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………….............................................. iv INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………. 1 1. MORCEAUX DE FANTAISIE, OP.3…………………………………………….. 3 2. MOMENTS MUSICAUX, OP.16……………………………………………….... 10 3. PRELUDES……………………………………………………………………….. 17 4. ETUDES-TABLEAUX…………………………………………………………… 36 5. SONATAS………………………………………………………………………… 51 6. VARIATIONS…………………………………………………………………….. 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………. -

ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) EARL WILD in Concert

EARL WILD In Concert 1983 & 1987 SCHUMANN Papillons Op.2 Sonata No.1 Op.11 Waldszenen Op.82 ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) EARL WILD in Concert Papillons, Op. 2 Sonata No. 1 in F sharp minor, Op. 11 Waldszenen, Op. 82 “As if all mental pictures must be shaped to fit one or two forms! As if each idea did not come into existence with its form ready-made! As if each work of art had not its own meaning and consequently its own form!” (Robert Schumann) No composer investigated the Romantic’s obsession with feeling and passion quite so thoroughly as Robert Alexander Schumann. For most of his life he suffered from inner torment - he died insane - but then some psychologists argue that madness is a necessary Robert Schumann attribute of genius. He was virtually self-taught (there were no musical antecedents in his family) which may account in part for having no qualms about dispensing with traditional forms of music and inventing his own (though in later years he wrote symphonies and quartets). Few men of his day knew more about music and musical theory than Schumann, but right from the start he was an innovator, a propagandist for the new, in love with literature almost as much as he was with music. His boldest contribution was to translate in his own picturesquely-entitled music - Arabesque, Kreisleriana, Carnaval, Papillons, Kinderszenen - his innermost thoughts and – 2 – emotions, unhindered by academic form. To Schumann, the pure idea from a cre- ative mind was itself sufficient aesthetic justification of its existence and for its form and content. -

Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice Tanya Gabrielian The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2762 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] RACHMANINOFF AND THE FLEXIBILITY OF THE SCORE: ISSUES REGARDING PERFORMANCE PRACTICE by TANYA GABRIELIAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2018 Ó 2018 TANYA GABRIELIAN All Rights Reserved ii Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice by Tanya Gabrielian This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Date Anne Swartz Chair of Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Geoffrey Burleson Sylvia Kahan Ursula Oppens THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Rachmaninoff and the Flexibility of the Score: Issues Regarding Performance Practice by Tanya Gabrielian Advisor: Geoffrey Burleson Sergei Rachmaninoff’s piano music is a staple of piano literature, but academia has been slower to embrace his works. Because he continued to compose firmly in the Romantic tradition at a time when Debussy, Stravinsky, and Schoenberg variously represented the vanguard of composition, Rachmaninoff’s popularity has consequently not been as robust in the musicological community. -

Westminster City Council's out and About Free Ticket Scheme Autumn

Westminster City Council’s Out and About free ticket scheme Autumn 2017 programme September Events Wednesday 13th September, 6pm – 7pm at Westminster Music Library Songs from my land and beyond A recital of songs from around the world by Argentinian soprano Susana Gilardoni Mirski accompanied by pianist Benedict Lewis-Smith Saturday 16th September at City of Westminster Archives Centre Open House weekend – no need to book Swinging Sixties themed open house day with tours of the search room, conservation and strong room for the public, spiced up with a small archive display called ‘Carnaby Street to King’s Road’. Tours will take place at 11 am, 12 noon, 1 pm, 2 pm, 3 pm and 4 pm, booking not required. Tuesday 19th September, 1pm at Wigmore Hall Benjamin Baker, violin Daniel Lebhardt, piano In 2016 Benjamin Baker won 1st Prize at the Young Concert Artists auditions in New York. The 2016/17 season saw him make his debuts with the Royal Philharmonic and Auckland Philharmonia Orchestras. Daniel Lebhardt won 1st Prize at the Young Concert Artists auditions in both Paris and New York in 2015. In 2016 he won the Most Promising Pianist prize at the Sydney International Piano Competition. Janacek: Violin Sonata Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 9 in A major Op. 47 ‘Kreutzer’ Saturday 30th September, 10am – 1pm at Westminster Music Library A Feast of Folk Songs: A Choral Workshop Musical Director Ruairi Glasheen will lead this singing workshop as part of this year’s Silver Sunday celebrations. Please note this event will take place on the Saturday! October Events Tuesday 3rd October, 1pm at Wigmore Hall Peter Moore, trombone Richard Uttley, piano In 2008, at the age of 12, Peter Moore became the youngest ever winner of the BBC Young Musician Competition. -

Schumann, Carnaval (1835)

SCHUMANN, CARNAVAL (1835) SCHUMANN, CARNAVAL 1835 “With Robert Schumann Romanticism came to full flower.” (Schonberg) FEATURES OF THE ROMANTIC ERA: ➢ Composer’s need for self-expression overrides other concerns. ➢ Unrestrained emotion. ➢ Emergence of formless music. ➢ Nationalism. ➢ Exoticism. ➢ Program music. ➢ Preoccupation with the supernatural. ➢ Ever enlarging orchestras, ever lengthening works. ➢ Emergence of the modern conductor. ➢ Miniatures. ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856): ➢ Born in Zwikau, Saxony, Germany. Father bookseller and novelist. Displayed early interest in music, age seven. ➢ As teenager influenced by the novels of Jean Paul Friedrich Richter, now obsolete, known simply as Jean Paul. ➢ Lost his father, 1826, at age 16. Mother encouraged him to go to law school. ➢ Began studying piano with Friedrich Wieck, in Leipzig, 1830. ➢ Right hand injury derailed piano career. ➢ Papillions 1831. Free form, thirteen movement piano music, made of dances that represent a masked ball, inspired by a Jean Paul novel. ➢ Die Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (“New Journal for Music”), 1834. Began career as a music critic with this magazine. 2 ➢ Engagement to Ernestine von Fricken, summer of 1834, daughter of a Bohemian noble, and Wieck’s piano pupil. The ill-fated relationship ended in 1835 when Schumann discovered she was illegitimate. ➢ In love with Clara Wieck, a piano prodigy and his teacher’s 15 year old daughter, 1835. She is destined to become “the most outstanding woman pianist of the nineteenth century” (Ostwald). ➢ Carnaval, 1834-35, inspired by Ernestine von Fricken. Like Papillions , a free form piano piece, but more elaborate. ➢ Marriage proposal to Clara Wieck, 1837; results in lawsuit by her father who opposes the union. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE www.kingslynnfestival.org.uk/press February 9 2009 Exciting variety for 2009 programme An exciting variety of entertainment, ranging from a top German orchestra to The Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain and Classic Brit award winners Blake, will give this summer’s King’s Lynn Festival especially broad appeal. With favourites from the classical music world, jazz, folk and top-name writers, artistic director Ambrose Miller said the line-up offered “something for everyone”. “By widening the appeal of the event we are not compromising our high standards but are continuing our tradition of excellence in all that we do,” he said. Classical music remains the cornerstone of the 59th Festival and includes a visit by Berlin Symphoniker, a leading German orchestra. Classic BRIT 2008 Album of the Year award winners Blake, four classically-trained singers who have successfully bridged the gap between pop and opera, will make their first appearance in the area. Their meteoric rise to stardom has included singing at the Queen’s 80th birthday party at Windsor Castle, and their version of Swing Low became the official anthem of the England team in the 2007 Rugby World Cup. The Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain has proved a sensation, selling out where ever they appear. Their first gig in 1985 was intended as a one-off but they were soon touring the world and have been described as “a musical phenomenon”. The Mike Piggott Hot Club Trio with perform their tribute to the legendary jazz violinist Stephane Grappelli, and folk music by Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick. -

Past Concerts - 1990/2016 2015/16

CONCERTS 1990/2015 1 PAST CONCERTS - 1990/2016 2015/16 Mote Hall / 10 October 2015 Taek-Gi Lee (piano) MSO / Wright Khachaturian - Three Dances from “Gayane” Rachmaninov - Piano Concerto 3 Rimsky-Korsakov - Scheherazade Mote Hall / 28 November 2015 Laura van der Heijden (cello) MSO / Wright Richard Strauss - Don Juan Walton - Cello Concerto Roussel - The Spider’s Banquet Elgar - In the South Mote Hall / 30 January 2016 Martin James Bartlett (piano) MSO / Wright Nielsen - Overture, Helios Mozart - Piano Concerto 12, K.414 Dvorak - Symphony 7 Mote Hall / 19 March 2016 Paul Beniston (trumpet) MSO / Wright Barber - Adagio for strings Arutiunian - Trumpet Concerto Mahler - Symphony 9 Mote Hall / 21 May 2016 Callum Smart (violin) MSO / Wright Borodin - Overture, Prince Igor Prokofiev - Violin Concerto 2 Tchaikovsky - Symphony 5 CONCERTS 1990/2015 2 2014/15 2013/14 Mote Hall / 11 October 2014 Mote Hall / 12 October 2013 Tae-Hyung Kim (piano) Laura van der Heijden (cello) MSO / Wright MSO / Wright Wagner – Overture Tannhäuser Britten – Four Sea Interludes from “Peter Beethoven – Piano Concerto 5 Grimes” “Emperor” Elgar – Cello Concerto Tchaikovsky – Symphony 1 “Winter Rachmaninov – Symphony 3 Daydreams” Mote Hall / 30 November 2013 Mote Hall / 29 November 2014 Tom Bettley (horn) Giovanni Guzzo (violin) MSO / Wright MSO / Wright Berlioz – Overture, Roman Carnival Copland – Appalachian Spring Glière – Horn Concerto Brahms – Violin Concerto Richard Strauss – Death and Vaughan Williams – Symphony 4 Transfiguration Stravinsky – Suite, The Firebird -

"Classical Piano" Competition in Dubai 4Th Round

29 Mahler - Symphony No.1 "Titan" Aram Khachaturian Concert Hall, Yerevan, Armenia Sep 2021 Orchestra Armenian State Symphony Orchestra Program Gustav Mahler - Symphony No.1 "Titan" 56' 29 Armenia International Music Festival Aram Khachaturian Concert Hall, Yerevan, Armenia Sep 2021 Orchestra Armenian State Symphony Orchestra Soloist Marc Bouchkov / violin Program Sergei Prokofiev - March from "The Love for Three Oranges" Sergei Prokofiev - Violin Concerto No.1 Modest Mussorgsky/Maurice Ravel - Pictures at an Exhibition 29 Concert with Mikhail Pletnev Aram Khachaturian Concert Hall, Yerevan, Armenia Oct 2021 Orchestra Armenian State Symphony Orchestra Soloist Mikhail Pletnev / piano Program Edward Grieg - Excerpts from "Peer Gynt" Suites 18' Alexey Shor - Piano Concerto "From My Bookshelf" 42' 14 Concert with the Elbląska Orkiestra Kameralna Nov 2021 ZPSM, Elbląg, Poland Orchestra Elbl?ska Orkiestra Kameralna Soloist Karolina Nowotczy?ska / violin Program Edward Grieg - Holberg Suite, Op.40 20’ Edward Mirzoyan - Lyric Poem “Shushanik” 6’ Ludwig van Beethoven - Violin Concerto in D major, Op.61 40’ (String Version) 14 Concert with Russian National Orchestra Prokofiev Concert Hall, Chelyabinsk, Russia Nov 2021 Orchestra Russian National Orchestra Soloist Sofia Yakovenko / violin Program P. Tchaikovsky - Violin Concerto L. W. Beethoven - Symphony No. 4 15 Tariverdiev Anniversary Concert Aram Khachaturian Concert Hall, Yerevan, Armenia Nov 2021 Orchestra Armenian State Symphony Orchestra Soloist Haik Kazazyan / violin Program TBA 22 Pre Tour