The Role of Narrative in Performing Schumann and Chopin's Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recasting Gender

RECASTING GENDER: 19TH CENTURY GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN THE LIVES AND WORKS OF ROBERT AND CLARA SCHUMANN A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Shelley Smith August, 2009 RECASTING GENDER: 19TH CENTURY GENDER CONSTRUCTIONS IN THE LIVES AND WORKS OF ROBERT AND CLARA SCHUMANN Shelley Smith Thesis Approved: Accepted: _________________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. James Lynn _________________________________ _________________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _________________________________ _________________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. THE SHAPING OF A FEMINIST VERNACULAR AND ITS APPLICATION TO 19TH-CENTURY MUSIC ..............................................1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 The Evolution of Feminism .....................................................................................3 19th-Century Gender Ideologies and Their Encoding in Music ...............................................................................................................8 Soundings of Sex ...................................................................................................19 II. ROBERT & CLARA SCHUMANN: EMBRACING AND DEFYING TRADITION -

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

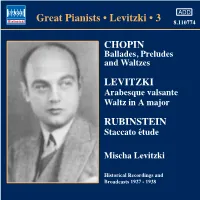

Print 110774Bk Levitzki

110774bk Levitzki 8/7/04 8:02 pm Page 5 Mischa Levitzki: Piano Recordings Vol. 3 Also available on Naxos ADD Gramophone Company Ltd., 1927-1933 RACHMANINOV: CHOPIN: @ Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5 3:22 Great Pianists • Levitzki • 3 8.110774 1 Prelude in C major, Op. 28 0:55 Recorded 21st November 1929 2 Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7 0:55 Matrix Cc 18200-1a; Cat. D 1809 3 Prelude in F major, Op. 28, No. 23 1:24 Recorded 21st November 1929 RCA Victor, 1938 Matrix Bb 18113-3a; Cat.DA1223 LEVITZKI: 4 Waltz No. 8 in A flat major, Op. 64, No. 3 3:00 # Waltz in A major, Op. 2 1:46 CHOPIN Recorded 19th November 1928 Recorded 5th May 1938; Matrix Cc 14770-1; Cat.ED18 Matrices BS 023101-1, BS 023101-1A (NP), Ballades, Preludes BS 023101-2, BS 023101-2A (NP); Cat. 2008-A 5 Waltz No. 11 in G flat major, $ Arabesque valsante, Op. 6 3:23 and Waltzes Op. 70, No. 1 2:26 Recorded 5th May 1938; Recorded 19th November 1928 Matrices BS 023100-1, BS 023100-1A (NP), Matrix Cc 14769-3; Cat.ED18 BS 023100-2, BS 023100-2A (NP), BS 023100-3, 6 Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47 6:26 BS023100-3A (NP); Cat. 2008-B Recorded 22nd November 1928 Broadcasts LEVITZKI Matrices Bb 11786-5 and 11787-5; Cat.EW64 26th January, 1935: 7 Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, CHOPIN: Arabesque valsante Op. 15, No. -

Chopin: Visual Contexts

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology g, 2011 © Department of Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland JACEK SZERSZENOWICZ (Łódź) Chopin: Visual Contexts ABSTRACT: The drawings, portraits and effigies of Chopin that were produced during his lifetime later became the basis for artists’ fantasies on the subject of his work. Just after the composer’s death, Teofil Kwiatkowski began to paint Bal w Hotel Lambert w Paryżu [Ball at the Hotel Lambert in Paris], symbolising the unfulfilled hopes of the Polish Great Emi gration that Chopin would join the mission to raise the spirit of the nation. Henryk Siemiradzki recalled the young musician’s visit to the Radziwiłł Palace in Poznań. The composer’s likeness appeared in symbolic representations of a psychological, ethnological and historical character. Traditional roots are referred to in the paintings of Feliks Wygrzywalski, Mazurek - grający Chopin [Mazurka - Chopin at the piano], with a couple of dancers in folk costume, and Stanisław Zawadzki, depicting the com poser with a roll of paper in his hand against the background of a forest, into the wall of which silhouettes of country children are merged, personifying folk music. Pictorial tales about music were also popularised by postcards. On one anonymous postcard, a ghost hovers over the playing musician, and the title Marsz żałobny Szopena [Chopin’s funeral march] suggests the connection with real apparitions that the composer occasional had when performing that work. In the visualisation of music, artists were often assisted by poets, who suggested associations and symbols. Correlations of content and style can be discerned, for ex ample, between Władysław Podkowinski’s painting Marsz żałobny Szopena and Kor nel Ujejski’s earlier poem Marsz pogrzebowy [Funeral march]. -

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY . It seems, however, far more likely that Chopin Notes on the musical text 3 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were intended a different grouping for this figure, e.g.: 7 added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation or . See the Source Commentary. are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an 3 inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, Bar 84 A gentle change of pedal is indicated on the final crotchet pedal indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in order to avoid the clash of g -f. in round brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all the markings in brackets. 2a & 2b. Nocturne in E flat major, Op. 9 No. 2 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, (versions with variants) 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small italic numerals , 1 2 3 4 5 . Wherever authentic fingering is enclosed in The sources indicate that while both performing the Nocturne parentheses this means that it was not present in the primary sources, and working on it with pupils, Chopin was introducing more or but added by Chopin to his pupils' copies. -

PROGRAM NOTES Franz Liszt Piano Concerto No. 2 in a Major

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Franz Liszt Born October 22, 1811, Raiding, Hungary. Died July 31, 1886, Bayreuth, Germany. Piano Concerto No. 2 in A Major Liszt composed this concerto in 1839 and revised it often, beginning in 1849. It was first performed on January 7, 1857, in Weimar, by Hans von Bronsart, with the composer conducting. The first American performance was given in Boston on October 5, 1870, by Anna Mehlig, with Theodore Thomas, who later founded the Chicago Symphony, conducting his own orchestra. The orchestra consists of three flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-two minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto were given at the Auditorium Theatre on March 1 and 2, 1901, with Leopold Godowsky as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on March 19, 20, and 21, 2009, with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as soloist and Jaap van Zweden conducting. The Orchestra first performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on August 4, 1945, with Leon Fleisher as soloist and Leonard Bernstein conducting, and most recently on July 3, 1996, with Misha Dichter as soloist and Hermann Michael conducting. Liszt is music’s misunderstood genius. The greatest pianist of his time, he often has been caricatured as a mad, intemperate virtuoso and as a shameless and -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Connecting Analysis and Performance: a Case Study for Developing an Effective Approach

Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic Volume 6 Issue 1 Article 8 October 2013 Connecting Analysis and Performance: A Case Study for Developing an Effective Approach Annie Yih University of California, Santa Barbara Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut Part of the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Yih, Annie (2013) "Connecting Analysis and Performance: A Case Study for Developing an Effective Approach," Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut/vol6/iss1/8 This A Music-Theoretical Matrix: Essays in Honor of Allen Forte (Part IV), edited by David Carson Berry is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/gamut. CONNECTING ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE: A CASE STUDY FOR DEVELOPING AN EFFECTIVE APPROACH ANNIE YIH ne of the purposes of teaching music theory is to connect the practice of analysis with O performance. However, several studies have expressed concern over a lack of connec- tion between the two, and they have raised questions concerning the performative qualities of traditional analytic theory.1 If theorists are to achieve one of the objectives of analysis in provid- ing performers with information for making decisions, and to develop what John Rink calls “informed intuition,” then they need to understand what types of analysis—and what details in an analysis—can be of service to performers.2 As we know, notation is not music; notation must be realized as music, and the first step involves score study. -

MAHANI TEAVE Concert Pianist Educator Environmental Activist

MAHANI TEAVE concert pianist educator environmental activist ABOUT MAHANI Award-winning pianist and humanitarian Mahani Teave is a pioneering artist who bridges the creative world with education and environmental activism. The only professional classical musician on her native Easter Island, she is an important cultural ambassador to this legendary, cloistered area of Chile. Her debut album, Rapa Nui Odyssey, launched as number one on the Classical Billboard charts and received raves from critics, including BBC Music Magazine, which noted her “natural pianism” and “magnificent artistry.” Believing in the profound, healing power of music, she has performed globally, from the stages of the world’s foremost concert halls on six continents, to hospitals, schools, jails, and low-income areas. Twice distinguished as one of the 100 Women Leaders of Chile, she has performed for its five past presidents and in its Embassy, along with those in Germany, Indonesia, Mexico, China, Japan, Ecuador, Korea, Mexico, and symbolic places including Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Chile’s Palacio de La Moneda, and Chilean Congress. Her passion for classical music, her local culture, and her Island’s environment, along with an intense commitment to high-quality music education for children, inspired Mahani to set aside her burgeoning career at the age of 30 and return to her Island to found the non-profit organization Toki Rapa Nui with Enrique Icka, creating the first School of Music and the Arts of Easter Island. A self-sustaining ecological wonder, the school offers both classical and traditional Polynesian lessons in various instruments to over 100 children. Toki Rapa Nui offers not only musical, but cultural, social and ecological support for its students and the area. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

1 the Consequences of Presumed Innocence: the Nineteenth-Century Reception of Joseph Haydn1 Leon Botstein

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-58052-6 - Haydn Studies Edited by W. Dean Sutcliffe Excerpt More information 1 The consequences of presumed innocence: the nineteenth-century reception of Joseph Haydn1 leon botstein 1 The Haydn paradox: from engaged affection to distant respect The mystery that plagues the contemporary conception and recep- tion of Haydn and his music has a long and remarkably unbroken history. Perhaps Haydn experienced the misfortune (an ironic one when one con- siders the frequency of premature deaths among his great contemporaries or near contemporaries) of living too long.Years before his death in 1809 he was considered so old that the French and English had already presumed him dead in 1805.2 Many wrote condolence letters and a Requiem Mass was planned in Paris. Haydn’s music was both familiar and venerated. Raphael Georg Kiesewetter (1773–1850), writing in Vienna in 1846, reflected the perspective of the beginning of the nineteenth century in his Geschichte der europaeisch-abendlaendischen oder unsrer heutigen Musik. Haydn had ‘ele- vated all of instrumental music to a never before anticipated level of perfec- tion’. Haydn had a ‘perfect knowledge of instrumental effects’ and with Mozart (for whom Haydn was the ‘example and ideal’) created a ‘new school which may be called the German or ...the “Viennese”school’.Theirs was the ‘golden age’ of music. Most significantly, Haydn’s instrumental works represented the standard of what was ‘true beauty’in music.3 Lurking beneath Kiesewetter’s praise of Haydn (and his discreet expressions of doubt about the novelties of Haydn’s successors, including 1 This essay is an expanded and revised form of my essay entitled ‘The Demise of Philosophical Listening’, in Elaine Sisman, ed., Haydn and his World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), pp. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music London’s Symphony Orchestra Celebrating LSO Members with 20+ years’ service. Visit lso.co.uk/1617photos for a full list. LSO Season 2016/17 Free concert programme London Symphony Orchestra LSO ST LUKE’S BBC RADIO 3 LUNCHTIME CONCERTS – AUTUMN 2016 MOZART & TCHAIKOVSKY LAWRENCE POWER & FRIENDS Ten musicians explore Tchaikovsky and his The violist is joined by some of his closest musical love of Mozart, through songs, piano trios, collaborators for a series that celebrates the string quartets and solo piano music. instrument as chamber music star, with works by with Pavel Kolesnikov, Sitkovetsky Piano Trio, Brahms, Schubert, Bach, Beethoven and others. Robin Tritschler, Iain Burnside & with Simon Crawford-Phillips, Paul Watkins, Ehnes String Quartet Vilde Frang, Nicolas Altstaedt & Vertavo Quartet For full listings visit lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Monday 19 September 2016 7.30pm Barbican Hall LSO ARTIST PORTRAIT Leif Ove Andsnes Beethoven Piano Sonata No 18 (‘The Hunt’) Sibelius Impromptus Op 5 Nos 5 and 6; Rondino Op 68 No 2; Elegiaco Op 76 No 10; Commodo from ‘Kyllikki‘ Op 41; Romance Op 24 No 9 INTERVAL Debussy Estampes Chopin Ballade No 2 in F major; Nocturne in F major; Ballade No 4 in F minor Leif Ove Andsnes piano Concert finishes at approximately 9.25pm 4 Welcome 19 September 2016 Welcome Kathryn McDowell Welcome to this evening’s concert at the Barbican Centre, where the LSO is delighted to welcome back Leif Ove Andsnes to perform a solo recital, and conclude the critically acclaimed LSO Artist Portrait series that he began with us last season.