Chopin: Visual Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print 110774Bk Levitzki

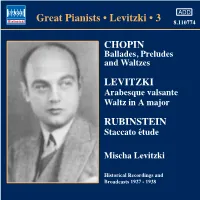

110774bk Levitzki 8/7/04 8:02 pm Page 5 Mischa Levitzki: Piano Recordings Vol. 3 Also available on Naxos ADD Gramophone Company Ltd., 1927-1933 RACHMANINOV: CHOPIN: @ Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5 3:22 Great Pianists • Levitzki • 3 8.110774 1 Prelude in C major, Op. 28 0:55 Recorded 21st November 1929 2 Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7 0:55 Matrix Cc 18200-1a; Cat. D 1809 3 Prelude in F major, Op. 28, No. 23 1:24 Recorded 21st November 1929 RCA Victor, 1938 Matrix Bb 18113-3a; Cat.DA1223 LEVITZKI: 4 Waltz No. 8 in A flat major, Op. 64, No. 3 3:00 # Waltz in A major, Op. 2 1:46 CHOPIN Recorded 19th November 1928 Recorded 5th May 1938; Matrix Cc 14770-1; Cat.ED18 Matrices BS 023101-1, BS 023101-1A (NP), Ballades, Preludes BS 023101-2, BS 023101-2A (NP); Cat. 2008-A 5 Waltz No. 11 in G flat major, $ Arabesque valsante, Op. 6 3:23 and Waltzes Op. 70, No. 1 2:26 Recorded 5th May 1938; Recorded 19th November 1928 Matrices BS 023100-1, BS 023100-1A (NP), Matrix Cc 14769-3; Cat.ED18 BS 023100-2, BS 023100-2A (NP), BS 023100-3, 6 Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47 6:26 BS023100-3A (NP); Cat. 2008-B Recorded 22nd November 1928 Broadcasts LEVITZKI Matrices Bb 11786-5 and 11787-5; Cat.EW64 26th January, 1935: 7 Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, CHOPIN: Arabesque valsante Op. 15, No. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music London’s Symphony Orchestra Celebrating LSO Members with 20+ years’ service. Visit lso.co.uk/1617photos for a full list. LSO Season 2016/17 Free concert programme London Symphony Orchestra LSO ST LUKE’S BBC RADIO 3 LUNCHTIME CONCERTS – AUTUMN 2016 MOZART & TCHAIKOVSKY LAWRENCE POWER & FRIENDS Ten musicians explore Tchaikovsky and his The violist is joined by some of his closest musical love of Mozart, through songs, piano trios, collaborators for a series that celebrates the string quartets and solo piano music. instrument as chamber music star, with works by with Pavel Kolesnikov, Sitkovetsky Piano Trio, Brahms, Schubert, Bach, Beethoven and others. Robin Tritschler, Iain Burnside & with Simon Crawford-Phillips, Paul Watkins, Ehnes String Quartet Vilde Frang, Nicolas Altstaedt & Vertavo Quartet For full listings visit lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Monday 19 September 2016 7.30pm Barbican Hall LSO ARTIST PORTRAIT Leif Ove Andsnes Beethoven Piano Sonata No 18 (‘The Hunt’) Sibelius Impromptus Op 5 Nos 5 and 6; Rondino Op 68 No 2; Elegiaco Op 76 No 10; Commodo from ‘Kyllikki‘ Op 41; Romance Op 24 No 9 INTERVAL Debussy Estampes Chopin Ballade No 2 in F major; Nocturne in F major; Ballade No 4 in F minor Leif Ove Andsnes piano Concert finishes at approximately 9.25pm 4 Welcome 19 September 2016 Welcome Kathryn McDowell Welcome to this evening’s concert at the Barbican Centre, where the LSO is delighted to welcome back Leif Ove Andsnes to perform a solo recital, and conclude the critically acclaimed LSO Artist Portrait series that he began with us last season. -

Ambiguity in the Themes of Chopin's First, Second, and Fourth Ballades

Ambiguity in the Themes of Chopin's First, Second, and Fourth Ballades William Rothstein There is a style of music which may be called natural, because it is not the offspring of science or reflection, but of an inspiration which sets at defiance all the strictness of rules and convention. I mean popular music, and especially that of the peasantry. How many exquisite compositions are born, live and die, among the peasantry, without ever having been dignified by a correct notation, without ever having deigned to be confined within the absolute limits of a distinct and definite theme. The unknown artist who improvises his rustic ballad while watching his flocks, or guiding his ploughshare, and there are such even in countries which would seem the least poetical, will experience great difficulty in retaining and fixing his fugitive fancies. He communicates his ballad to other musicians, children like himself of nature, and these circulate it from hamlet to hamlet, from cot to cot, each modifying it according to the bent of his own individual genius. It is hence that these pastoral songs and romances, so artlessly striking or so deeply touching, are for the most part lost, and rarely exist above a single century in the memory of their rustic composers. Musicians completely formed under the rules of art rarely trouble themselves to collect them. Many even disdain them from very lack of an intelligence sufficiently pure, and a taste sufficiently elevated to admit of their appreciating them. Others are dismayed by the difficulties which they encounter the moment they endeavor to discover that true and original version, which, perhaps, no longer retains its existence even in the mind of its author, and which certainly was never at any time recognised as a definite and invariable type by any one of his numerous interpreters... -

DUX 1270-1 / 2016 FRYDERYK CHOPIN Piano Concertos Works

DUX 1270-1 / 2016 ____________________________________________________________________ FRYDERYK CHOPIN Piano concertos Works for piano solo Fryderyk CHOPIN (1810-1849) CD 1 *Piano Concerto in E minor Op.11 *Piano Concerto in F minor Op.21 CD 2 *Polonaise in A flat major Op.53 *Fantasy-Impromptu in C sharp minor Op.66 *Nocturne in F sharp major Op.15 No.2 *Scherzo in B flat minor Op.31 *Rondo à la Krakowiak in F major Op.14 *** Piotr PALECZNY - piano Kwartet Prima Vista : Krzysztof BZOWKA - 1st violin, Józef KOLINEK - 2nd violin Dariusz KISIELINSKI – viola, Jerzy MURANTY - cello Janusz MARYNOWSKI - double bass _______________________________________________________________________________________________ DUX Małgorzata Polańska & Lech Tołwiński ul. Morskie Oko 2, 02-511 Warszawa tel./fax (48 22) 849-11-31, (48 22) 849-18-59 e-mail: [email protected], www.dux.pl Aleksandra Kitka-Coutellier – International Relations kitka@dux “Hats off gentlemen - a genius” - wrote Robert Schumann in his famous review entitled Ein Opus 2 , published in the Leipzig periodical ‘Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung’ (No.49, 7 December 1831), having listened to Chopin’s Variations on a Theme from Mozart’s Don Giovanni. The genius was born on 1 March in Żelazowa Wola, west of Warsaw. The local parish register contains the following entry: “In the year one thousand eight hundred ten, on the twenty third day of the month of April, at three o’clock in the afternoon. Before me, parish priest of Brochów in the district of Sochaczew in the Department of Warsaw, appeared Mikołaj Chopin, the father, aged forty, domiciled in Żelazowa Wola, and showed me a male child which was born in his house on the twenty second day of February of this year at six o’clock in the evening, declaring that it was the child of himself and of Justyna born Krzyżanowska, aged twenty eight, his spouse, and that it was his wish to give him two names, Fryderyk Franciszek. -

New Sound 30 Jim Samson Exploring Chopin's Polish 'Ballade'

New Sound 30 Jim Samson Exploring Chopin’s Polish ’Ballade’ Article received on February 27, 2007 UDC 78.071.1 Chopin F. Jim Samson EXPLORING CHOPIN’S ‘POLISH BALLADE’ Abstract: Each stage of the source chain of Chopin’s Op. 38 is described. Theories of genre are discussed. Late nineteenth-century descriptions are related to intertextual associations to produce a hermeneutical reading of the work. Key words: Source chain; genre; topos; narrative; intertext; extramusical Preamble It was in Majorca - on 14 December 1839 - that Chopin wrote to Julian Fontana, 'I expect to send you my Preludes and Ballade shortly', referring here to the Second Ballade.1 He had already composed the main outlines of the ballade prior to Majorca (Félicien Mallefille referred to it, interestingly enough, as the 'Polish ballade' in a letter that pre-dated the excursion), but he refined it and completed it during the Majorcan adventure. Indeed it is entirely possible that it was on Majorca that he wrote what Schumann called the 'impassioned episodes', referring of course to the figurations, since he had already performed the opening section by itself on several occasions. My intention here is to comment briefly on salient aspects of the text of the ballade with reference to its extant sources. Following that, I will say something of an interpretative nature about the work, focusing on questions of intertextuality. Texts Unusually for Chopin, virtually every stage of an archetypal source chain is represented for this work. The manuscript and early printed sources are as follows: A1 There is an autograph fragment (bars 11-12) in the Album of Ivar Hallstrom (currently held in the Music History Museum in Stockholm). -

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY Notes on the musical text the first and third beat. The pedal depressed at the beginning of bar 31 can be lifted after the figuration ends on the first note of bar 32. p. 15 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were Bars 8, 10, 18 & 24 R.H. The lower note of the arpeggiated chord added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation should be struck together with the first semiquaver played by the are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an L.H. inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. p. 16 Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, pedal Bars 32-33 It is better to play the arpeggios in a continuous indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in round fashion, i.e. b with the R.H. after g with the L.H. brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all 4. Prelude in E minor, Op. 28 no. 4 the markings in brackets. p. 17 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, Bars 11 & 19 R.H. The signs written most probably by Chopin on 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small one of his pupils’ copies indicate that the grace-note should be italic numerals, 1 2 3 4 5. -

Making and Defending a Polish Town: “Lwуw” (Lemberg), 1848-1914

Making and Defending a Polish Town: "Lwow" (Lemberg), 1848-1914 HARALD BINDER ANY EAST CENTRAL EUROPEAN towns and cities bear several names, reflecting the ethnic and religious diversity once characteristic of M the region. The town chosen in 1772 by the Habsburgs as capital of their newly acquired province of Galicia serves as an example. In the second half of the nineteenth century Ruthenian national populists referred to the city as "L'viv"; Russophiles designated the city "L'vov." For Poles and Polo- nized Jews the town was "Lwow," and for Germans as well as German- and Yiddish-speaking Jews the city was "Lemberg." The ethnic and linguistic reality was, in fact, much less clear than these divisions would suggest. For much of the period of Habsburg rule, language barriers remained permeable. The city's inhabitants were multilingual, often employing different languages depending on the type of communication in which they were engaged. By the late nineteenth century, however, nationalists came to regard language as one of the most important objective characteristics defining their respective national communities. For example, Ruthenian intellectuals felt more com- fortable communicating in Polish, but, when acting as politicians, they spoke and wrote in one of the varieties of "Ruthenian." The many names for the Galician capital can also be related to specific periods in the history of the city. From this perspective, moving from one name to another mirrors shifting power relations and cultural orientation. The seventeenth century historian Bartlomiej .Zimorowicz chose such a chronological structure for his "History of the City of Lwow." He traced the fate of the town as it changed from a "Ruthenian" (from 1270) to a "German" (from 1350) to a "Polish" city (from 1550).1 Zimorowicz's method of dividing Center for Austrian Studies Austrian History Yearbook 34 (2003): 57-81. -

The Unique Cultural & Innnovative Twelfty 1820

Chekhov reading The Seagull to the Moscow Art Theatre Group, Stanislavski, Olga Knipper THE UNIQUE CULTURAL & INNNOVATIVE TWELFTY 1820-1939, by JACQUES CORY 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS No. of Page INSPIRATION 5 INTRODUCTION 6 THE METHODOLOGY OF THE BOOK 8 CULTURE IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES IN THE “CENTURY”/TWELFTY 1820-1939 14 LITERATURE 16 NOBEL PRIZES IN LITERATURE 16 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN 1820-1939, WITH COMMENTS AND LISTS OF BOOKS 37 CORY'S LIST OF BEST AUTHORS IN TWELFTY 1820-1939 39 THE 3 MOST SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – FRENCH, ENGLISH, GERMAN 39 THE 3 MORE SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – SPANISH, RUSSIAN, ITALIAN 46 THE 10 SIGNIFICANT LITERATURES – PORTUGUESE, BRAZILIAN, DUTCH, CZECH, GREEK, POLISH, SWEDISH, NORWEGIAN, DANISH, FINNISH 50 12 OTHER EUROPEAN LITERATURES – ROMANIAN, TURKISH, HUNGARIAN, SERBIAN, CROATIAN, UKRAINIAN (20 EACH), AND IRISH GAELIC, BULGARIAN, ALBANIAN, ARMENIAN, GEORGIAN, LITHUANIAN (10 EACH) 56 TOTAL OF NOS. OF AUTHORS IN EUROPEAN LANGUAGES BY CLUSTERS 59 JEWISH LANGUAGES LITERATURES 60 LITERATURES IN NON-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES 74 CORY'S LIST OF THE BEST BOOKS IN LITERATURE IN 1860-1899 78 3 SURVEY ON THE MOST/MORE/SIGNIFICANT LITERATURE/ART/MUSIC IN THE ROMANTICISM/REALISM/MODERNISM ERAS 113 ROMANTICISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 113 Analysis of the Results of the Romantic Era 125 REALISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 128 Analysis of the Results of the Realism/Naturalism Era 150 MODERNISM IN LITERATURE, ART AND MUSIC 153 Analysis of the Results of the Modernism Era 168 Analysis of the Results of the Total Period of 1820-1939 -

Music – Our Passion

2011 recent releases and highlights for piano Music – Our Passion. Hal Leonard is proud to be exclusive U.S. distributor for the distinguished Munich-based music publisher G. Henle Verlag. Henle Urtext editions are highly regarded for impeccable research of composers’ manuscripts, proofs, first editions and other relevant sources. Henle editions are universally praised for: • authoritative musical accuracy • the world’s highest quality music engraving • insightful critical commentary • helpful fingerings • premium, custom made paper • long-lasting binding for a lifetime of use Among the world’s leading classical pianists who have endorsed, performed and recorded Henle Urtext editions are: Leif Ove Andsnes • Vladimir Ashkenazy • Paul Badura-Skoda • Daniel Barenboim • Alfred Brendel • Rudolf Buchbinder • Philippe Entremont • Marc-André Hamelin • Vladimir Horowitz • Evgeny Kissin • Lang Lang • Elisabeth Leonskaja • Yundi Li • Gerhard Oppitz • Murray Perahia • András Schiff • Grigory Sokolov • Mitsuko Uchida • Lars Vogt REcent Urtext Editions for Piano Urtext editions FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: PIANO ROBERT SCHUMANN: SEVEN are softcover SONATA IN C MINOR, OP. 4 PIANO PIECES IN FUGHETTA unless clothbound is indicated. 51480942 ..................................................... $17.95 FORM, OP. 126 FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: POLONAISE 51480907 ..................................................... $13.95 Search description, IN A-FLAT MAJOR, OP. 53 ROBERT SCHUMANN: THREE contents, editors, REVISED EDITION PIANO SONATAS FOR THE and all available Henle publications -

Od Oświecenia Ku Romantyzmowi I Dalej : Autorzy, Dzieła, Czytelnicy

Od oświecenia ku romantyzmowi i dalej... PRACE NAUKOWE UNIWERSYTETU ŚLĄSKIEGO W KATOWICACH N R 2238 Od oświecenia ku romantyzmowi i dalej... Autorzy - dzieła - czytelnicy pod redakcją Marka Piechoty i Janusza Ryby Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego Katowice 2004 Redaktor serii: Historia Literatury Polskiej Jerzy Paszek R ecenzent Józef Bachórz 3 3 3 1 1 0 Spis treści W stę p ....................................................................................................................... 7 Agnieszka Kwiatkowska „Rozumne zawody” Polemiki polskiego oświecenia.................................... 9 Janusz Ryba „Mały” P otocki....................................................................................................... 40 Monika Stankiewicz-Kopeć Znaczenie roku 1817 w polskim procesie litera c k im .................................. 49 Magdalena Bąk W arsztat Mickiewicza tłu m ac z a ....................................................................... 72 Damian Noras Ziemia - kobieta - płodność. (O pierwiastku żeńskim w Panu Tadeuszu). 89 Aleksandra Rutkowska Czasy teraz na literaturę złe - Mickiewicz na rynku wydawniczym w pierw szej połowie XIX wieku. Rekonesans............................................................. 108 Jacek Lyszczyna Zemsta Aleksandra Fredry wobec klęski powstania listopadowego . 127 Maciej Szargot Koniec baśni. O [Panu Tadeuszu] J. Słowackiego Mariusz Pleszak O biograficznych kontekstach Tłumaczeń Szopena Kornela Ujejskiego . 146 Barbara Szargot Legenda przeciw legendzie. O powieści J.I. Kraszewskiego -

Slowacki's Chopin

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 9, 2011 © Department of Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, Poland AGATA SEWERYN (Lublin) Slowacki’s Chopin ABSTRACT: Supposed analogies between Fryderyk Chopin and Juliusz Słowacki form a recurring thread that runs through the subject literature of Romantic culture. Legions of literati, critics, literary scholars and musicologists have either attempted to find affinities between Chopin and Słowacki (on the level of both biography and creative output) or else have energetically demonstrated the groundlessness of all analogies, opinions and assumptions. ConseQuently, stereotypes have been formed and then strengthened concerning the relations between the two creative artists, particularly the conviction of Slowacki’s dislike of Chopin and his music, which - in the opinion of many scholars - the poet simply did not understand. Considerations of this kind most often centre on a famous letter written by Słowacki to his mother in February 1845. However, a careful reading of this letter and its comparison with Slowacki’s other utterances on the subject of Chopin shows that opinions of the poet’s alleged insanity, petty-mindedness or lack of subtlety in his contacts with Chopin’s music are most unjust. The analysed letter is not so much anti-Chopin as anti-Romantic. It inscribes itself perfectly in the context of the thinking of “the Słowacki of the last years”, since the poet negates crucial aesthetic features of Romantic music, but at the same time criticises his own works: W Szwajcarii [In Switzerland] and, in other letters, Godzina myśli [An hour of thought] and the “picture of the age”, the poetical novel Lambro. -

On Collective Forms of the Chopin Cult in Poland During the Nineteenth Century

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology 9, 2011 © Department of Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland MAGDALENA DZIADEK (Poznań) On collective forms of the Chopin cult in Poland during the nineteenth century ABSTRACT: This article is devoted to specific forms of the Chopin cult that developed in Poland during the nineteenth century. Due to the socio-political situation in the country during the period of the Partitions and the influence of tradition, this cult was manifest first and foremost in the joint experiencing of anniversaries connected with the composer on the part of members of local communities or the entire nation. The basic medium of that experience was the press, in which biographic articles, sketches on his music and also poetical works devoted to the composer were an obligatory part of the anniversaries of Chopin’s birth and death. In this way, the Chopin cult in Poland became primarily a literary phenomenon. Also linked to the traditional culture of the letter that was Polish culture of the nineteenth century is the characteristic form of the Chopin cult known as the obchód. The communal character of the obchód was re- flected in its specific form and content. One of the prime concerns was the need to forcibly communicate the fact that Chopin’s music was a national good. Thus at the centre of the theatrically-managed obchód stood an orator or actor declaiming against the background of Chopin’s music. For the purposes of these declamations, a huge amount of literature was produced, examples of which are discussed in the article. Another characteristic “anniversary” product were re-workings of Chopin composi- tions for large orchestral and choral forces, treated as “ceremonial”.