The Ballades of Frederic Chopin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Young Narcyza Żmichowska's Reception of Western Cultural

Rocznik Komparatystyczny – Comparative Yearbook – Komparatistisches Jahrbuch 7 (2016) DOI: 10.18276/rk.2016.7-16 Ursula Phillips UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES) With Open Eyes: The Young Narcyza Żmichowska’s Reception of Western Cultural Influences Narcyza Żmichowska (1819–1876) is not a name instantly recognizable outside Poland. In the English-speaking world, however, she is not unknown thanks to research on women’s history, where she is usually discussed in connection with the group of women with whom she was associated in the 1840s known as the Enthu- siasts (Fraisse and Perrot, 1993: 485). It is thanks to the appearance of Grażyna Borkowska’s book in English (2001) that her achievements as a literary author have become better known among Slavists and women’s literature researchers outside Poland. An English translation of Żmichowska’s best known novel Poganka (The Heathen) appeared in 2012 with a substantial introduction placing the work in both its Polish and European contemporary contexts (Żmichowska, 2012). Recently, this novel has featured alongside works by Charlotte Brontë, Daphne du Maurier and others, in a PhD dissertation inspired by psychoanalytic theories of femininity and mirroring, thereby proving her potential for comparative analysis (Naszkowska, 2012). The aim of the current article is to discuss this non-Polish context, and how foreign inspirations made their way into Żmichowska’s work and thinking. Like many other Polish cultural figures, Żmichowska maintained a close con- nection with France, although she never became an émigrée. Her literary activity is a testament nonetheless to how, despite spending more or less her whole life in the partitioned Polish lands, mostly in the Russian partition but also in the 1840s in the Poznań region of the Prussian, she was able to keep abreast of philosophical, political and literary developments in France and Germany and, in the latter part of her life, in Britain, North America, Italy and Scandinavia. -

Romantic Listening Key

Name ______________________________ Romantic Listening Key Number: 7.1 CD 5/47 pg. 297 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 4th mvmt Composer: Berlioz Genre: Program Symphony Characteristics Texture: ____________________________________________________ Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: timp start, high bsn solo Number: 7.2 CD 6/11 pg 339 Title: The Moldau Composer: Smetana Genre: symphonic poem Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: flute start Sections: two springs, the river, forest hunt, peasant wedding, moonlight dance of river nymphs, the river, the rapids, the river at its widest point, Vysehrad the ancient castle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.3 CD 5/51 pg 229 Title: Symphonie Fantastique, 5th mvmt (Dream of a Witch's Sabbath) Composer: Berlioz Genre: program symphony Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: funeral chimes, clarinet idee fix, trills & grace notes Number: 7.4 website Title: 1812 Overture Composer: Tchaikovsky Genre: concert overture Characteristics Texture: homophonic Text: _______________________________________________________ Voicing/Instrumentation: orchestra What I heard: soft beginning, hunter motive, “Go Napoleon”, the battle Name ______________________________ Number: 7.5 website Title: The Sorcerer's Apprentice -

Canções E Modinhas: a Lecture Recital of Brazilian Art Song Repertoire Marcía Porter, Soprano and Lynn Kompass, Piano

Canções e modinhas: A lecture recital of Brazilian art song repertoire Marcía Porter, soprano and Lynn Kompass, piano As the wealth of possibilities continues to expand for students to study the vocal music and cultures of other countries, it has become increasingly important for voice teachers and coaches to augment their knowledge of repertoire from these various other non-traditional classical music cultures. I first became interested in Brazilian art song repertoire while pursuing my doctorate at the University of Michigan. One of my degree recitals included Ernani Braga’s Cinco canções nordestinas do folclore brasileiro (Five songs of northeastern Brazilian folklore), a group of songs based on Afro-Brazilian folk melodies and themes. Since 2002, I have been studying and researching classical Brazilian song literature and have programmed the music of Brazilian composers on nearly every recital since my days at the University of Michigan; several recitals have been entirely of Brazilian music. My love for the music and culture resulted in my first trip to Brazil in 2003. I have traveled there since then, most recently as a Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Professor at the Universidade de São Paulo. There is an abundance of Brazilian art song repertoire generally unknown in the United States. The music reflects the influence of several cultures, among them African, European, and Amerindian. A recorded history of Brazil’s rich music tradition can be traced back to the sixteenth-century colonial period. However, prior to colonization, the Amerindians who populated Brazil had their own tradition, which included music used in rituals and in other aspects of life. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

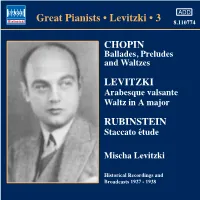

Print 110774Bk Levitzki

110774bk Levitzki 8/7/04 8:02 pm Page 5 Mischa Levitzki: Piano Recordings Vol. 3 Also available on Naxos ADD Gramophone Company Ltd., 1927-1933 RACHMANINOV: CHOPIN: @ Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5 3:22 Great Pianists • Levitzki • 3 8.110774 1 Prelude in C major, Op. 28 0:55 Recorded 21st November 1929 2 Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7 0:55 Matrix Cc 18200-1a; Cat. D 1809 3 Prelude in F major, Op. 28, No. 23 1:24 Recorded 21st November 1929 RCA Victor, 1938 Matrix Bb 18113-3a; Cat.DA1223 LEVITZKI: 4 Waltz No. 8 in A flat major, Op. 64, No. 3 3:00 # Waltz in A major, Op. 2 1:46 CHOPIN Recorded 19th November 1928 Recorded 5th May 1938; Matrix Cc 14770-1; Cat.ED18 Matrices BS 023101-1, BS 023101-1A (NP), Ballades, Preludes BS 023101-2, BS 023101-2A (NP); Cat. 2008-A 5 Waltz No. 11 in G flat major, $ Arabesque valsante, Op. 6 3:23 and Waltzes Op. 70, No. 1 2:26 Recorded 5th May 1938; Recorded 19th November 1928 Matrices BS 023100-1, BS 023100-1A (NP), Matrix Cc 14769-3; Cat.ED18 BS 023100-2, BS 023100-2A (NP), BS 023100-3, 6 Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47 6:26 BS023100-3A (NP); Cat. 2008-B Recorded 22nd November 1928 Broadcasts LEVITZKI Matrices Bb 11786-5 and 11787-5; Cat.EW64 26th January, 1935: 7 Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, CHOPIN: Arabesque valsante Op. 15, No. -

Halle, the City of Music a Journey Through the History of Music

HALLE, THE CITY OF MUSIC A JOURNEY THROUGH THE HISTORY OF MUSIC 8 WC 9 Wardrobe Ticket office Tour 1 2 7 6 5 4 3 EXHIBITION IN WILHELM FRIEDEMANN BACH HOUSE Wilhelm Friedemann Bach House at Grosse Klausstrasse 12 is one of the most important Renaissance houses in the city of Halle and was formerly the place of residence of Johann Sebastian Bach’s eldest son. An extension built in 1835 houses on its first floor an exhibition which is well worth a visit: “Halle, the City of Music”. 1 Halle, the City of Music 5 Johann Friedrich Reichardt and Carl Loewe Halle has a rich musical history, traces of which are still Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) is known as a partially visible today. Minnesingers and wandering musicographer, composer and the publisher of numerous musicians visited Giebichenstein Castle back in the lieder. He moved to Giebichenstein near Halle in 1794. Middle Ages. The Moritzburg and later the Neue On his estate, which was viewed as the centre of Residenz court under Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg Romanticism, he received numerous famous figures reached its heyday during the Renaissance. The city’s including Ludwig Tieck, Clemens Brentano, Novalis, three ancient churches – Marktkirche, St. Ulrich and St. Joseph von Eichendorff and Johann Wolfgang von Moritz – have always played an important role in Goethe. He organised musical performances at his home musical culture. Germany’s oldest boys’ choir, the in which his musically gifted daughters and the young Stadtsingechor, sang here. With the founding of Halle Carl Loewe took part. University in 1694, the middle classes began to develop Carl Loewe (1796–1869), born in Löbejün, spent his and with them, a middle-class musical culture. -

Chopin: Visual Contexts

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology g, 2011 © Department of Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland JACEK SZERSZENOWICZ (Łódź) Chopin: Visual Contexts ABSTRACT: The drawings, portraits and effigies of Chopin that were produced during his lifetime later became the basis for artists’ fantasies on the subject of his work. Just after the composer’s death, Teofil Kwiatkowski began to paint Bal w Hotel Lambert w Paryżu [Ball at the Hotel Lambert in Paris], symbolising the unfulfilled hopes of the Polish Great Emi gration that Chopin would join the mission to raise the spirit of the nation. Henryk Siemiradzki recalled the young musician’s visit to the Radziwiłł Palace in Poznań. The composer’s likeness appeared in symbolic representations of a psychological, ethnological and historical character. Traditional roots are referred to in the paintings of Feliks Wygrzywalski, Mazurek - grający Chopin [Mazurka - Chopin at the piano], with a couple of dancers in folk costume, and Stanisław Zawadzki, depicting the com poser with a roll of paper in his hand against the background of a forest, into the wall of which silhouettes of country children are merged, personifying folk music. Pictorial tales about music were also popularised by postcards. On one anonymous postcard, a ghost hovers over the playing musician, and the title Marsz żałobny Szopena [Chopin’s funeral march] suggests the connection with real apparitions that the composer occasional had when performing that work. In the visualisation of music, artists were often assisted by poets, who suggested associations and symbols. Correlations of content and style can be discerned, for ex ample, between Władysław Podkowinski’s painting Marsz żałobny Szopena and Kor nel Ujejski’s earlier poem Marsz pogrzebowy [Funeral march]. -

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His Broadcasting Career Covers Both Radio and Television

557643bk VW US 16/8/05 5:02 pm Page 5 8.557643 Iain Burnside Songs of Travel (Words by Robert Louis Stevenson) 24:03 1 The Vagabond 3:24 The English Song Series • 14 DDD Iain Burnside enjoys a unique reputation as pianist and broadcaster, forged through his commitment to the song 2 Let Beauty awake 1:57 repertoire and his collaborations with leading international singers, including Dame Margaret Price, Susan Chilcott, 3 The Roadside Fire 2:17 Galina Gorchakova, Adrianne Pieczonka, Amanda Roocroft, Yvonne Kenny and Susan Bickley; David Daniels, 4 John Mark Ainsley, Mark Padmore and Bryn Terfel. He has also worked with some outstanding younger singers, Youth and Love 3:34 including Lisa Milne, Sally Matthews, Sarah Connolly; William Dazeley, Roderick Williams and Jonathan Lemalu. 5 In Dreams 2:18 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His broadcasting career covers both radio and television. He continues to present BBC Radio 3’s Voices programme, 6 The Infinite Shining Heavens 2:15 and has recently been honoured with a Sony Radio Award. His innovative programming led to highly acclaimed 7 Whither must I wander? 4:14 recordings comprising songs by Schoenberg with Sarah Connolly and Roderick Williams, Debussy with Lisa Milne 8 Songs of Travel and Susan Bickley, and Copland with Susan Chilcott. His television involvement includes the Cardiff Singer of the Bright is the ring of words 2:10 World, Leeds International Piano Competition and BBC Young Musician of the Year. He has devised concert series 9 I have trod the upward and the downward slope 1:54 The House of Life • Four poems by Fredegond Shove for a number of organizations, among them the acclaimed Century Songs for the Bath Festival and The Crucible, Sheffield, the International Song Recital Series at London’s South Bank Centre, and the Finzi Friends’ triennial The House of Life (Words by Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 26:27 festival of English Song in Ludlow. -

Mélodie French Art Song Recital; Wednesday, April 28, 2021

UCM Music Presents UCM Music Presents MÉLODIE FRENCH ART SONG RECITAL Dr. Stella D. Roden and Students MÉLODIE FRENCH ART SONG RECITAL Dr. Stella D. Roden and Students Hart Recital Hall Cynthia Groff, piano Hart Recital Hall Cynthia Groff, piano Wednesday, April 28, 2021 Denise Robinson, piano Wednesday, April 28, 2021 Denise Robinson, piano 7:00 p.m. 7:00 p.m. In consideration of the performers, other audience members, and the live recording of this concert, please In consideration of the performers, other audience members, and the live recording of this concert, please silence all devices before the performance. Parents are expected to be responsible for their children's behavior. silence all devices before the performance. Parents are expected to be responsible for their children's behavior. Le Charme Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) Le Charme Ernest Chausson (1855-1899) Lucas Henley, baritone Lucas Henley, baritone Les cygnes Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947) Les cygnes Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947) Anna Sanderson, soprano Anna Sanderson, soprano Lydia Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Lydia Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Alex Scharfenberg, tenor Alex Scharfenberg, tenor Ici-bas! Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Ici-bas! Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Gabrielle Moore, soprano Gabrielle Moore, soprano Fleur desséchée Pauline García Viardot (1821-1910) Fleur desséchée Pauline García Viardot (1821-1910) Janie Turner, soprano Janie Turner, soprano Le lever de la lune Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) Le lever de la lune Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) Nikolas Baumert, baritone Nikolas Baumert, baritone continued on reverse continued on reverse Become a Concert Insider! Text the word “concerts” to 660-248-0496 Become a Concert Insider! Text the word “concerts” to 660-248-0496 or visit ucmmusic.com to sign up for news about upcoming events. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

8.111327 Bk Cortot EU 13/7/08 22:47 Page 4

8.111327 bk Cortot EU 13/7/08 22:47 Page 4 GREAT PIANISTS • ALFRED CORTOT Fryderyk CHOPIN (1810 - 1849) Waldszenen, Op. 82 CHOPIN: Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 35 Piano Sonata No. 2 in B flat minor, Op. 35 * No. 7. Vogel als Prophet 2:36 “Funeral March” 17:36 Recorded 19th April 1948 1 I. Grave - Doppio movimento 5:25 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 SCHUMANN: Kinderszenen Op. 15 2 II. Scherzo 4:50 First issued on HMV ALP 1197 3 III. Marche funèbre: Lento 5:42 Matrix no.: 0EA 12922 4 IV. Finale: Presto 1:39 Carnaval, Op. 9 Recorded 7th-8th May 1953 Carnaval, Op. 9 25:29 in EMI Abbey Road Studio No. 3 ( No. 1. Préambule 2:36 RED CORT First issued on RCA Victor LHMV 18 ) No. 2. Pierrot 1:08 LF OT ¡ No. 3. Arlequin 0:43 A Robert SCHUMANN (1810 - 1856) ™ No. 4. Valse noble 1:19 Kinderszenen, Op. 15 17:15 £ 5 No. 5. Eusebius 1:30 No. 1. Von fremden Ländern und Menschen 1:39 ¢ No. 6. Florestan 0:53 (About foreign lands and peoples) – 6 No. 7. Coquette 1:01 No. 2. Curiose Geschichte 0:58 § No. 8. Réplique 0:26 (A curious story) ¶ 7 Sphinx 1-3 0:23 No. 3. Hasche-Mann 0:34 • No. 9. Papillons 0:43 (Catch me if you can) ª 8 No. 10. A.S.C.H. - S.C.H.A. No. 4. Bittendes Kind 0:51 (Lettres dansantes) 0:38 (Pleading child) º 9 No. 11. Chiarina 0:49 No.