New Sound 30 Jim Samson Exploring Chopin's Polish 'Ballade'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

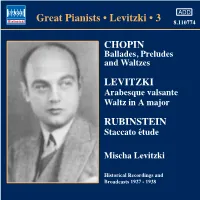

Print 110774Bk Levitzki

110774bk Levitzki 8/7/04 8:02 pm Page 5 Mischa Levitzki: Piano Recordings Vol. 3 Also available on Naxos ADD Gramophone Company Ltd., 1927-1933 RACHMANINOV: CHOPIN: @ Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5 3:22 Great Pianists • Levitzki • 3 8.110774 1 Prelude in C major, Op. 28 0:55 Recorded 21st November 1929 2 Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7 0:55 Matrix Cc 18200-1a; Cat. D 1809 3 Prelude in F major, Op. 28, No. 23 1:24 Recorded 21st November 1929 RCA Victor, 1938 Matrix Bb 18113-3a; Cat.DA1223 LEVITZKI: 4 Waltz No. 8 in A flat major, Op. 64, No. 3 3:00 # Waltz in A major, Op. 2 1:46 CHOPIN Recorded 19th November 1928 Recorded 5th May 1938; Matrix Cc 14770-1; Cat.ED18 Matrices BS 023101-1, BS 023101-1A (NP), Ballades, Preludes BS 023101-2, BS 023101-2A (NP); Cat. 2008-A 5 Waltz No. 11 in G flat major, $ Arabesque valsante, Op. 6 3:23 and Waltzes Op. 70, No. 1 2:26 Recorded 5th May 1938; Recorded 19th November 1928 Matrices BS 023100-1, BS 023100-1A (NP), Matrix Cc 14769-3; Cat.ED18 BS 023100-2, BS 023100-2A (NP), BS 023100-3, 6 Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47 6:26 BS023100-3A (NP); Cat. 2008-B Recorded 22nd November 1928 Broadcasts LEVITZKI Matrices Bb 11786-5 and 11787-5; Cat.EW64 26th January, 1935: 7 Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, CHOPIN: Arabesque valsante Op. 15, No. -

Chopin: Visual Contexts

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology g, 2011 © Department of Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland JACEK SZERSZENOWICZ (Łódź) Chopin: Visual Contexts ABSTRACT: The drawings, portraits and effigies of Chopin that were produced during his lifetime later became the basis for artists’ fantasies on the subject of his work. Just after the composer’s death, Teofil Kwiatkowski began to paint Bal w Hotel Lambert w Paryżu [Ball at the Hotel Lambert in Paris], symbolising the unfulfilled hopes of the Polish Great Emi gration that Chopin would join the mission to raise the spirit of the nation. Henryk Siemiradzki recalled the young musician’s visit to the Radziwiłł Palace in Poznań. The composer’s likeness appeared in symbolic representations of a psychological, ethnological and historical character. Traditional roots are referred to in the paintings of Feliks Wygrzywalski, Mazurek - grający Chopin [Mazurka - Chopin at the piano], with a couple of dancers in folk costume, and Stanisław Zawadzki, depicting the com poser with a roll of paper in his hand against the background of a forest, into the wall of which silhouettes of country children are merged, personifying folk music. Pictorial tales about music were also popularised by postcards. On one anonymous postcard, a ghost hovers over the playing musician, and the title Marsz żałobny Szopena [Chopin’s funeral march] suggests the connection with real apparitions that the composer occasional had when performing that work. In the visualisation of music, artists were often assisted by poets, who suggested associations and symbols. Correlations of content and style can be discerned, for ex ample, between Władysław Podkowinski’s painting Marsz żałobny Szopena and Kor nel Ujejski’s earlier poem Marsz pogrzebowy [Funeral march]. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music London’s Symphony Orchestra Celebrating LSO Members with 20+ years’ service. Visit lso.co.uk/1617photos for a full list. LSO Season 2016/17 Free concert programme London Symphony Orchestra LSO ST LUKE’S BBC RADIO 3 LUNCHTIME CONCERTS – AUTUMN 2016 MOZART & TCHAIKOVSKY LAWRENCE POWER & FRIENDS Ten musicians explore Tchaikovsky and his The violist is joined by some of his closest musical love of Mozart, through songs, piano trios, collaborators for a series that celebrates the string quartets and solo piano music. instrument as chamber music star, with works by with Pavel Kolesnikov, Sitkovetsky Piano Trio, Brahms, Schubert, Bach, Beethoven and others. Robin Tritschler, Iain Burnside & with Simon Crawford-Phillips, Paul Watkins, Ehnes String Quartet Vilde Frang, Nicolas Altstaedt & Vertavo Quartet For full listings visit lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Monday 19 September 2016 7.30pm Barbican Hall LSO ARTIST PORTRAIT Leif Ove Andsnes Beethoven Piano Sonata No 18 (‘The Hunt’) Sibelius Impromptus Op 5 Nos 5 and 6; Rondino Op 68 No 2; Elegiaco Op 76 No 10; Commodo from ‘Kyllikki‘ Op 41; Romance Op 24 No 9 INTERVAL Debussy Estampes Chopin Ballade No 2 in F major; Nocturne in F major; Ballade No 4 in F minor Leif Ove Andsnes piano Concert finishes at approximately 9.25pm 4 Welcome 19 September 2016 Welcome Kathryn McDowell Welcome to this evening’s concert at the Barbican Centre, where the LSO is delighted to welcome back Leif Ove Andsnes to perform a solo recital, and conclude the critically acclaimed LSO Artist Portrait series that he began with us last season. -

Ambiguity in the Themes of Chopin's First, Second, and Fourth Ballades

Ambiguity in the Themes of Chopin's First, Second, and Fourth Ballades William Rothstein There is a style of music which may be called natural, because it is not the offspring of science or reflection, but of an inspiration which sets at defiance all the strictness of rules and convention. I mean popular music, and especially that of the peasantry. How many exquisite compositions are born, live and die, among the peasantry, without ever having been dignified by a correct notation, without ever having deigned to be confined within the absolute limits of a distinct and definite theme. The unknown artist who improvises his rustic ballad while watching his flocks, or guiding his ploughshare, and there are such even in countries which would seem the least poetical, will experience great difficulty in retaining and fixing his fugitive fancies. He communicates his ballad to other musicians, children like himself of nature, and these circulate it from hamlet to hamlet, from cot to cot, each modifying it according to the bent of his own individual genius. It is hence that these pastoral songs and romances, so artlessly striking or so deeply touching, are for the most part lost, and rarely exist above a single century in the memory of their rustic composers. Musicians completely formed under the rules of art rarely trouble themselves to collect them. Many even disdain them from very lack of an intelligence sufficiently pure, and a taste sufficiently elevated to admit of their appreciating them. Others are dismayed by the difficulties which they encounter the moment they endeavor to discover that true and original version, which, perhaps, no longer retains its existence even in the mind of its author, and which certainly was never at any time recognised as a definite and invariable type by any one of his numerous interpreters... -

DUX 1270-1 / 2016 FRYDERYK CHOPIN Piano Concertos Works

DUX 1270-1 / 2016 ____________________________________________________________________ FRYDERYK CHOPIN Piano concertos Works for piano solo Fryderyk CHOPIN (1810-1849) CD 1 *Piano Concerto in E minor Op.11 *Piano Concerto in F minor Op.21 CD 2 *Polonaise in A flat major Op.53 *Fantasy-Impromptu in C sharp minor Op.66 *Nocturne in F sharp major Op.15 No.2 *Scherzo in B flat minor Op.31 *Rondo à la Krakowiak in F major Op.14 *** Piotr PALECZNY - piano Kwartet Prima Vista : Krzysztof BZOWKA - 1st violin, Józef KOLINEK - 2nd violin Dariusz KISIELINSKI – viola, Jerzy MURANTY - cello Janusz MARYNOWSKI - double bass _______________________________________________________________________________________________ DUX Małgorzata Polańska & Lech Tołwiński ul. Morskie Oko 2, 02-511 Warszawa tel./fax (48 22) 849-11-31, (48 22) 849-18-59 e-mail: [email protected], www.dux.pl Aleksandra Kitka-Coutellier – International Relations kitka@dux “Hats off gentlemen - a genius” - wrote Robert Schumann in his famous review entitled Ein Opus 2 , published in the Leipzig periodical ‘Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung’ (No.49, 7 December 1831), having listened to Chopin’s Variations on a Theme from Mozart’s Don Giovanni. The genius was born on 1 March in Żelazowa Wola, west of Warsaw. The local parish register contains the following entry: “In the year one thousand eight hundred ten, on the twenty third day of the month of April, at three o’clock in the afternoon. Before me, parish priest of Brochów in the district of Sochaczew in the Department of Warsaw, appeared Mikołaj Chopin, the father, aged forty, domiciled in Żelazowa Wola, and showed me a male child which was born in his house on the twenty second day of February of this year at six o’clock in the evening, declaring that it was the child of himself and of Justyna born Krzyżanowska, aged twenty eight, his spouse, and that it was his wish to give him two names, Fryderyk Franciszek. -

Performance Commentary

PERFORMANCE COMMENTARY Notes on the musical text the first and third beat. The pedal depressed at the beginning of bar 31 can be lifted after the figuration ends on the first note of bar 32. p. 15 The variants marked as ossia were given this label by Chopin or were Bars 8, 10, 18 & 24 R.H. The lower note of the arpeggiated chord added in his hand to pupils' copies; variants without this designation should be struck together with the first semiquaver played by the are the result of discrepancies in the texts of authentic versions or an L.H. inability to establish an unambiguous reading of the text. p. 16 Minor authentic alternatives (single notes, ornaments, slurs, accents, pedal Bars 32-33 It is better to play the arpeggios in a continuous indications, etc.) that can be regarded as variants are enclosed in round fashion, i.e. b with the R.H. after g with the L.H. brackets ( ), whilst editorial additions are written in square brackets [ ]. Pianists who are not interested in editorial questions, and want to base their performance on a single text, unhampered by variants, are recom- mended to use the music printed in the principal staves, including all 4. Prelude in E minor, Op. 28 no. 4 the markings in brackets. p. 17 Chopin's original fingering is indicated in large bold-type numerals, Bars 11 & 19 R.H. The signs written most probably by Chopin on 1 2 3 4 5, in contrast to the editors' fingering which is written in small one of his pupils’ copies indicate that the grace-note should be italic numerals, 1 2 3 4 5. -

Music – Our Passion

2011 recent releases and highlights for piano Music – Our Passion. Hal Leonard is proud to be exclusive U.S. distributor for the distinguished Munich-based music publisher G. Henle Verlag. Henle Urtext editions are highly regarded for impeccable research of composers’ manuscripts, proofs, first editions and other relevant sources. Henle editions are universally praised for: • authoritative musical accuracy • the world’s highest quality music engraving • insightful critical commentary • helpful fingerings • premium, custom made paper • long-lasting binding for a lifetime of use Among the world’s leading classical pianists who have endorsed, performed and recorded Henle Urtext editions are: Leif Ove Andsnes • Vladimir Ashkenazy • Paul Badura-Skoda • Daniel Barenboim • Alfred Brendel • Rudolf Buchbinder • Philippe Entremont • Marc-André Hamelin • Vladimir Horowitz • Evgeny Kissin • Lang Lang • Elisabeth Leonskaja • Yundi Li • Gerhard Oppitz • Murray Perahia • András Schiff • Grigory Sokolov • Mitsuko Uchida • Lars Vogt REcent Urtext Editions for Piano Urtext editions FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: PIANO ROBERT SCHUMANN: SEVEN are softcover SONATA IN C MINOR, OP. 4 PIANO PIECES IN FUGHETTA unless clothbound is indicated. 51480942 ..................................................... $17.95 FORM, OP. 126 FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN: POLONAISE 51480907 ..................................................... $13.95 Search description, IN A-FLAT MAJOR, OP. 53 ROBERT SCHUMANN: THREE contents, editors, REVISED EDITION PIANO SONATAS FOR THE and all available Henle publications -

MTO 22.4: Broesche, Glenn Gould, Spliced

Volume 22, Number 4, December 2016 Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory Garreth P. Broesche NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.4/mto.16.22.4.broesche.php KEYWORDS: Glenn Gould, music and technology, recording, filmmaking, ontology, Walter Benjamin, aura, Sergei Eisenstein, Johannes Brahms ABSTRACT: Glenn Gould often drew an analogy: live theater is to film as concert performance is to studio recording. In his writings, Gould cites one finished “performance” created by splicing together two contrasting interpretations of a piece; through editing, the finished version somehow becomes more than the sum of its parts. Here Gould’s use of editing appears to invoke montage technique in a manner similar to one of its uses in film: contrasting images (interpretations) are juxtaposed, bequeathing responsibility to the viewer (listener) to infer meaning not explicitly present in either. To paraphrase Walter Benjamin, the use of montage technique separates filmmaking from live theater, altering the ontological status of the former and elevating it to an independent art form. Do the ways in which Gould employs technology support the claim that there is a similar relationship between live and studio music? For all the extant literature on Gould, there is little that discusses—in detail—his actual studio process. Scholars have tended to take Gould at his word. However, I believe that only by placing the focus squarely on the historical truth may we evaluate his recording/filmmaking analogy. This paper centers on a detailed audio analysis of one Gould performance: his 1981 recording of a Brahms Ballade. -

The Ballades of Frederic Chopin

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 12-1-1981 The alB lades of Frederic Chopin Janell E. Brakel Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Brakel, Janell E., "The alB lades of Frederic Chopin" (1981). Theses and Dissertations. 451. https://commons.und.edu/theses/451 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ' 1 f. 1 'c' ,.!'l)~r,T(' ,.,H.,L l, ]3"11 .... J_.;/\ D' ••• ; 'J''1' · ...:'"· 1"i'_ ·, l·,r\ _ . Li1· Janl"ll E. Brakel Bachelor af Science, Mayville State Coll~ge, 1978 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillnl\'!nt of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota December 1981 I ' ' ,........I 'J-·liis 'l'he:;i.s su:Omitted by Janell E. Brakel in partir1l fulfillment of tl1e requirements for the Degree of !>laster nf Art:s from the University of North Dakota is h~reby ap proved Ly the Faculty Advisory Conunittee under whom the work has been done. ' / I' -'' , ~ _/ ,. ' , ,'I / - ,' ' I ./ , I' -~ v (Chairman) c - ' ' ' - ' This Thesis meets the standards for appearance and confor~s to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of i'Jorth Dakota, and is hereby approved . -

Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture by Tony Hsiu Lin a Disserta

Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture By Tony Hsiu Lin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Anne Nesbet, Co-Chair Professor David Frick, Co-Chair Professor Robert P. Hughes Professor James Davies Spring 2014 Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture © 2014 by Tony Hsiu Lin Abstract Myth and Appropriation: Fryderyk Chopin in the Context of Russian and Polish Literature and Culture by Tony Hsiu Lin Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Anne Nesbet, Co-Chair Professor David Frick, Co-Chair Fryderyk Chopin’s fame today is too often taken for granted. Chopin lived in a time when Poland did not exist politically, and the history of his reception must take into consideration the role played by Poland’s occupying powers. Prior to 1918, and arguably thereafter as well, Poles saw Chopin as central to their “imagined community.” They endowed national meaning to Chopin and his music, but the tendency to glorify the composer was in a constant state of negotiation with the political circumstances of the time. This dissertation investigates the history of Chopin’s reception by focusing on several events that would prove essential to preserving and propagating his legacy. Chapter 1 outlines the indispensable role some Russians played in memorializing Chopin, epitomized by Milii Balakirev’s initiative to erect a monument in Chopin’s birthplace Żelazowa Wola in 1894. -

The Role of Narrative in Performing Schumann and Chopin's Music

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Spring 2017 The oler of narrative in performing Schumann and Chopin’s music Yu-Wen Chen James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Chen, Yu-Wen, "The or le of narrative in performing Schumann and Chopin’s music" (2017). Dissertations. 140. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/140 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Narrative in Performing Schumann and Chopin’s Music Yu-Wen Chen A document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music May 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Gabriel Dobner Committee Members/ Readers: Eric Ruple John Peterson ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am thankful for the numerous people that have contributed to this document. I would like to first thank my committee members: to Dr. Gabriel Dobner, my applied teacher and advisor, for all of his musical expertise and unwavering support, for all these years, I have been fortunate to have his guidance; to Dr. John Peterson, for helping my understanding of musical narrative and providing suggestions regarding analysis and writing; to Dr. Eric Ruple, for his continued patience and gracious encouragement. I would especially like to take this opportunity to express my gratefulness to my former teacher Harvey Wedeen (1927-2015) who supported and inspired me during my years of musical studies at Temple University. -

An Examination of the Value of Score Alteration in Virtuosic Piano Repertoire

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 The Mutability of the Score: An Examination of the Value of Score Alteration in Virtuosic Piano Repertoire Wayne Weng The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3708 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE MUTABILITY OF THE SCORE: AN EXAMINATION OF THE VALUE OF SCORE ALTERATION IN VIRTUOSIC PIANO REPERTOIRE BY WAYNE WENG A dissertation suBmitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 WAYNE WENG ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii The Mutability of the Score: An Examination of the Value of Score Alteration in Virtuosic Piano Repertoire By Wayne Weng This manuscript has Been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Ursula Oppens ____________________ ____________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Norman Carey ____________________ ____________________________ Date Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Scott Burnham Raymond Erickson John Musto THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Mutability of the Score: An Examination of the Value of Score Alteration in Virtuosic Piano Repertoire by Wayne Weng Advisor: Scott Burnham This dissertation is a defense of the value of score alteration in virtuosic piano repertoire.