An Examination of the Value of Score Alteration in Virtuosic Piano Repertoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

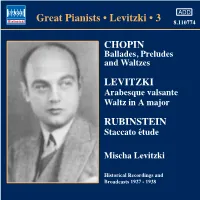

Print 110774Bk Levitzki

110774bk Levitzki 8/7/04 8:02 pm Page 5 Mischa Levitzki: Piano Recordings Vol. 3 Also available on Naxos ADD Gramophone Company Ltd., 1927-1933 RACHMANINOV: CHOPIN: @ Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5 3:22 Great Pianists • Levitzki • 3 8.110774 1 Prelude in C major, Op. 28 0:55 Recorded 21st November 1929 2 Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7 0:55 Matrix Cc 18200-1a; Cat. D 1809 3 Prelude in F major, Op. 28, No. 23 1:24 Recorded 21st November 1929 RCA Victor, 1938 Matrix Bb 18113-3a; Cat.DA1223 LEVITZKI: 4 Waltz No. 8 in A flat major, Op. 64, No. 3 3:00 # Waltz in A major, Op. 2 1:46 CHOPIN Recorded 19th November 1928 Recorded 5th May 1938; Matrix Cc 14770-1; Cat.ED18 Matrices BS 023101-1, BS 023101-1A (NP), Ballades, Preludes BS 023101-2, BS 023101-2A (NP); Cat. 2008-A 5 Waltz No. 11 in G flat major, $ Arabesque valsante, Op. 6 3:23 and Waltzes Op. 70, No. 1 2:26 Recorded 5th May 1938; Recorded 19th November 1928 Matrices BS 023100-1, BS 023100-1A (NP), Matrix Cc 14769-3; Cat.ED18 BS 023100-2, BS 023100-2A (NP), BS 023100-3, 6 Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47 6:26 BS023100-3A (NP); Cat. 2008-B Recorded 22nd November 1928 Broadcasts LEVITZKI Matrices Bb 11786-5 and 11787-5; Cat.EW64 26th January, 1935: 7 Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, CHOPIN: Arabesque valsante Op. 15, No. -

Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (Guest Post)*

The Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (guest post)* Artur Schnabel Austrian pianist Artur Schnabel has been called “the man who invented Beethoven”... a strange thing to say considering Schnabel was born more than half a century after Beethoven, universally recognized as the greatest composer in Europe, died in 1827. What, then, did Artur Schnabel invent? The 32 piano sonatas of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) represent one of the great artistic achievements in human history, and stand as the musical autobiography of the great composer's maturity, from his 25th until his 53rd year, four years before his death. The fruit of those years mark a staggering creative journey that began and ended in the composer's adopted home of Vienna, “Music Central” to the German-speaking world. Beethoven's musical path led from the domain of Haydn and Mozart to the world of his late period, when the agonizing progress of his deafness had become complete. By then, Beethoven's musical narrative had begun to speak a new language, proceeding according to a new logic that left many listeners behind. While the beauties of his music and his deep genius were generally recognized, at the same time, it was thought by some critics that Beethoven frequently smudged things up with his overly- bold, unfettered invention, even well before his final period: Beethoven, who is often bizarre and baroque, takes at times the majestic flight of an eagle, and then creeps in rocky pathways. He first fills the soul with sweet melancholy, and then shatters it by a mass of shattered chords. -

CHRISTOPH PRÉGARDIEN CYPRIEN KATSARIS Auf Flügeln Des Gesanges Romantic Songs and Piano Transcriptions

CHRISTOPH PRÉGARDIEN CYPRIEN KATSARIS Auf Flügeln des Gesanges Romantic songs and piano transcriptions 1 CHRISTOPH PRÉGARDIEN CYPRIEN KATSARIS Auf Flügeln des Gesanges Romantic songs and piano transcriptions FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) CLARA SCHUMANN [1] Die Forelle, Op. 32, D. 530 2:16 [9] 6 Lieder, Op. 23 3:31 FRANZ LISZT (1810-1886) No. 3: Geheimes Flüstern hier und dort [2] 6 Melodien von Franz Schubert, S. 563 3:02 FRANZ LISZT No. 6: Die Forelle (1st version) [10] Lieder von Robert und Clara Schumann, S. 569 2:26 No. 10: Geheimes Flüstern hier und dort FRANZ SCHUBERT [3] Schwanengesang, D. 957 2:46 FRANZ LISZT No. 1: Liebesbotschaft [11] Im Rhein, im schönen Strome (2nd version), S. 272 2:49 LEOPOLD GODOWSKY (1870-1938) [12] Buch der Lieder I, S. 531 2:17 [4] Transcription of Liebesbotschaft 3:31 No. 2: Im Rhein, im schönen Strome FELIX MENDELSSOHN-BARTHOLDY (1809-1847) RICHARD WAGNER (1813-1883) [5] 6 Gesänge, Op. 34 2:53 [13] 5 Gedichte für eine Frauenstimme (Wesendonck-Lieder), WWV 91 4:28 No. 2: Auf Flügeln des Gesanges No. 5: Träume FRANZ LISZT AUGUST STRADAL (1860-1930) [6] Mendelssohns Lieder, S. 547 3:28 [14] Transcription of Träume 4:30 No. 1: Auf Flügeln des Gesanges HUGO WOLF (1860-1903) ROBERT SCHUMANN (1810-1856) [15] Anakreons Grab 2:52 [7] Liederkreis, Op. 39 1:16 BRUNO HINZE-REINHOLD (1877-1964) No. 12: Frühlingsnacht [16] 10 Piano Pieces after Hugo Wolf Lieder 2:54 CLARA SCHUMANN (1819-1896) No. 6: Idylle after Anakreons Grab [8] 30 Lieder und Gesänge von Robert Schumann 1:18 No. -

Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme By

RACHMANINOFF’S RHAPSODY ON A THEME BY PAGANINI, OP. 43: ANALYSIS AND DISCOURSE Heejung Kang, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor and Program Coordinator Stephen Slottow, Minor Professor Josef Banowetz, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Interim Chair of Piano Jessie Eschbach, Chair of Keyboard Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrill, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kang, Heejung, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43: Analysis and Discourse. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2004, 169 pp., 40 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 39 titles. This dissertation on Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43 is divided into four parts: 1) historical background and the state of the sources, 2) analysis, 3) semantic issues related to analysis (discourse), and 4) performance and analysis. The analytical study, which constitutes the main body of this research, demonstrates how Rachmaninoff organically produces the variations in relation to the theme, designs the large-scale tonal and formal organization, and unifies the theme and variations as a whole. The selected analytical approach is linear in orientation - that is, Schenkerian. In the course of the analysis, close attention is paid to motivic detail; the analytical chapter carefully examines how the tonal structure and motivic elements in the theme are transformed, repeated, concealed, and expanded throughout the variations. As documented by a study of the manuscripts, the analysis also facilitates insight into the genesis and structure of the Rhapsody. -

David Dubal Tem Dado Recitais De Piano E Masterclasses Em Todo O

David Dubal tem dado recitais de piano e masterclasses em todo o mundo, e foi jurado de competições internacionais de piano (incluindo o Van Cliburn International Piano Competition). Ele gravou vários CDs em conjunto com o pianista Stanley Waldoff para a gravadora Musical Heritage Society, e três discos foram remasterizados e lançados em CD pela gravadora Arkiv. Em 2013, Dubal participou do filme Holandês Nostalgia: a Música de Wim Statius Müller, comentando sobre as músicas do compositor, o qual foi seu professor em Ohio. Dubal lecionou na Juilliard School de 1983 a 2018, e na Manhattan School of Music de 1994 a 2015. Dubal escreveu vários livros, incluindo a Arte do Piano, Noites com Horowitz, Conversas com Menuhin, Reflexões do Teclado, Conversas com João Carlos Martins, Lembrando Horowitz e O Essencial Cânone da Música Clássica (um guia enciclopédico dos compositores proeminentes). Ele também escreveu e apresentou o documentário A Era Dourada do Piano, premiado com um Emmy e produzido por Peter Rosen. Dubal dá palestras semanais, Noites com Piano, na Good Shepherd-Faith Presbyterian Church, em Nova Iorque. Ele deu inúmeras palestras no Metropolitan Museum of Art sobre os grandes pianistas, mudanças sociais, história da música e tradição do piano. Suas palestras estão disponíveis em seu site: https://www.pianoevenings.com/david-dubal. Dubal é o anfitrião das palestras Sobre o Piano, um programa de performances comparativas de piano na WWFM e o anfitrião de Reflexões do Teclado, uma exploração semanal de gravações de piano, produzido na WQXR-FM. No final da década de 1990, ele apresentou uma série de programas de rádio intitulado The American Century, com foco em obras musicais de compositores Americanos do século XX, agora disponíveis no YouTube. -

Chopin: Visual Contexts

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology g, 2011 © Department of Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland JACEK SZERSZENOWICZ (Łódź) Chopin: Visual Contexts ABSTRACT: The drawings, portraits and effigies of Chopin that were produced during his lifetime later became the basis for artists’ fantasies on the subject of his work. Just after the composer’s death, Teofil Kwiatkowski began to paint Bal w Hotel Lambert w Paryżu [Ball at the Hotel Lambert in Paris], symbolising the unfulfilled hopes of the Polish Great Emi gration that Chopin would join the mission to raise the spirit of the nation. Henryk Siemiradzki recalled the young musician’s visit to the Radziwiłł Palace in Poznań. The composer’s likeness appeared in symbolic representations of a psychological, ethnological and historical character. Traditional roots are referred to in the paintings of Feliks Wygrzywalski, Mazurek - grający Chopin [Mazurka - Chopin at the piano], with a couple of dancers in folk costume, and Stanisław Zawadzki, depicting the com poser with a roll of paper in his hand against the background of a forest, into the wall of which silhouettes of country children are merged, personifying folk music. Pictorial tales about music were also popularised by postcards. On one anonymous postcard, a ghost hovers over the playing musician, and the title Marsz żałobny Szopena [Chopin’s funeral march] suggests the connection with real apparitions that the composer occasional had when performing that work. In the visualisation of music, artists were often assisted by poets, who suggested associations and symbols. Correlations of content and style can be discerned, for ex ample, between Władysław Podkowinski’s painting Marsz żałobny Szopena and Kor nel Ujejski’s earlier poem Marsz pogrzebowy [Funeral march]. -

Myra Hess Had to Wait for Her Ultimate Breakthrough in Her English Homeland; for This Reason, She Initially Had to Earn Her Living by Teaching

Hess, Myra Irene Scharrer. However, Myra Hess had to wait for her ultimate breakthrough in her English homeland; for this reason, she initially had to earn her living by teaching. Her first major success abroad was her debut in Amster- dam, where she performed Schumann's Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54 with the Concertgebouw Orchestra un- der Willem Mengelberg in 1912. In 1922 followed her de- but in New York, where she was celebrated with equal en- thusiasm. Her career advanced rapidly from that point onwards, and she rose to the position of one of the most successful pianists in her homeland during the ensuing years. During the 1930s, she undertook extended concert tours throughout all of Europe, including the Scandinavi- an countries, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania, Tur- key, Yugoslavia, Germany, France and Holland. At the be- ginning of the Second World War, when all of London's concert halls were closed, she founded the legendary "Lunchtime Recitals" at the National Gallery, offering the London public a broad spectrum of high-quality pro- grammes with both young and established musicians. She herself performed at the National Gallery 146 times. The concerts were held without interruption until 10 Ap- Die Pianistin Myra Hess ril 1946. In 1941 Myra Hess was honoured with the title "Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire" Myra Hess for her special efforts on behalf of musical life in her ho- meland. After the Second World War, the meanwhile fa- * 25 February 1890 in Hampstead (im heutigen mous pianist regularly gave concerts in her native count- Londoner Stadtbezirk Camden), England ry and in the USA, where she enjoyed great popularity. -

The Pianist's Freedom and the Work's Constrictions

The Pianist’s Freedom and the Work’s Constrictions What Tempo Fluctuation in Bach and Chopin Indicate Alisa Yuko Bernhard A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Alisa Yuko Bernhard 10 November 2016 i Abstract The concept of the musical work has triggered much discussion: it has been defined and redefined, and at times attacked and deconstructed, by writers including Wolterstorff, Goodman, Levinson, Davies, Nattiez, Goehr, Abbate and Parmer, to name but a few. More often than not, it is treated either as an abstract sound-structure or, in contrast, as a culturally constructed concept, even a chimera. But what is a musical work to the performer, actively engaged in a “relationship” with the work he or she is interpreting? This question, not asked often enough in scholarship, can be used to yield fascinating insights into the ontological status of the work. My thesis therefore explores the relationship between the musical work and the performance, with a specific focus on classical pianists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I make use of two methodological starting-points for considering the nature of the work. Firstly, I survey what pianists have said and written in interviews and biographies regarding their role as interpreters of works. Secondly, I analyse pianists’ use of tempo fluctuation at structurally significant moments in a selection of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach and Frederic Chopin. -

Rezension Für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Rezension für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings Ludwig van Beethoven | Claude Debussy | Maurice Ravel | Frédéric Chopin | Sergei Prokofiev | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 4CD aud 21.404 Radio Stephansdom CD des Tages, 04.09.2009 ( - 2009.09.04) Aufnahmen, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Glasklar, "gespitzter Ton" und... Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Neue Musikzeitung 9/2009 (Andreas Kolb - 2009.09.01) Konzertprogramm im Wandel Konzertprogramm im Wandel Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Piano News September/Oktober 2009, 5/2009 (Carsten Dürer - 2009.09.01) Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 388 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton CD der Woche, 14.09.2009 (Wilfried Bestehorn, Oliver Schwesig - 2009.09.14) In einem Gemeinschaftsprojekt zwischen dem Label "audite" und Deutschlandradio Kultur werden seit Jahren einmalige Aufnahmen aus den RIAS-Archiven auf CD herausgebracht. Inzwischen sind bereits 40 CD's erschienen mit Aufnahmen von Furtwängler und Fricsay, von Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau u. v. a. Die jüngste Produktion dieser Reihe "The Early RIAS-Recordings" enthält bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Die Einspielungen von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Chopin zeigen den jungen Pianisten an der Schwelle zu internationalem Ruhm. Die Meinung unserer Musikkritiker: Eine repräsentative Auswahl bisher unveröffentlichter Aufnahmen, die aber bereits alle Namen enthält, die für Guldas späteres Repertoire bedeutend werden sollten: Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Chopin. -

Crafted Financial Planning & Wealth Creation Solutions

CRAFTED FINANCIAL PLANNING & WEALTH CREATION SOLUTIONS Saturday 28 July 7.30pm Federation Concert Hall Hobart MASTER 8 MASTER Marko Letonja conductor TCHAIKOVSKY Simon Trpcˇeski piano Symphony No 6, Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo BERLIOZ Allegro con grazia Roméo et Juliette, Love Scene Allegro molto vivace Duration 18 mins Finale (Adagio lamentoso – Andante) LISZT Duration 46 mins Piano Concerto No 2 Adagio sostenuto assai – Allegro agitato This concert will end at approximately assai – Allegro moderato – Allegro 9.30 pm. deciso – Marziale, un poco meno Allegro – Un poco meno mosso – Allegro animato Duration 21 mins INTERVAL Duration 20 mins 03 6294 0000 | UNICAWEALTH.COM.AU Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra concerts are broadcast and streamed throughout Australia and around the world by ABC Classic FM. We would appreciate your cooperation in keeping coughing to a minimum. Please ensure that your mobile phone is switched off. 26 27 Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) Roméo et Juliette: symphonie ‘If you ask me which of my works I prefer, dramatique, Op 17 the answer is that of most artists: the love Second Part: Love Scene scene in Roméo et Juliette.’ No wonder Berlioz was proud of this section, where we hear the young Capulet revellers ‘…I settled on the idea of a symphony leave the ball and the orchestra take Marko Letonja is Chief Conductor and Macedonian pianist Simon Trpcˇeski has with chorus, soloists and choral recitative centre stage for one of the composer’s Artistic Director of the Tasmanian Symphony performed with many of the world’s leading on the sublime and perennial theme of finest movements, the Adagio. -

MAHANI TEAVE Concert Pianist Educator Environmental Activist

MAHANI TEAVE concert pianist educator environmental activist ABOUT MAHANI Award-winning pianist and humanitarian Mahani Teave is a pioneering artist who bridges the creative world with education and environmental activism. The only professional classical musician on her native Easter Island, she is an important cultural ambassador to this legendary, cloistered area of Chile. Her debut album, Rapa Nui Odyssey, launched as number one on the Classical Billboard charts and received raves from critics, including BBC Music Magazine, which noted her “natural pianism” and “magnificent artistry.” Believing in the profound, healing power of music, she has performed globally, from the stages of the world’s foremost concert halls on six continents, to hospitals, schools, jails, and low-income areas. Twice distinguished as one of the 100 Women Leaders of Chile, she has performed for its five past presidents and in its Embassy, along with those in Germany, Indonesia, Mexico, China, Japan, Ecuador, Korea, Mexico, and symbolic places including Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate, Chile’s Palacio de La Moneda, and Chilean Congress. Her passion for classical music, her local culture, and her Island’s environment, along with an intense commitment to high-quality music education for children, inspired Mahani to set aside her burgeoning career at the age of 30 and return to her Island to found the non-profit organization Toki Rapa Nui with Enrique Icka, creating the first School of Music and the Arts of Easter Island. A self-sustaining ecological wonder, the school offers both classical and traditional Polynesian lessons in various instruments to over 100 children. Toki Rapa Nui offers not only musical, but cultural, social and ecological support for its students and the area. -

Franz Liszt's Piano Transcriptions of "Sonetto 104 Del Petrarca". Nam Yeung Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1997 Franz Liszt's Piano Transcriptions of "Sonetto 104 Del Petrarca". Nam Yeung Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Yeung, Nam, "Franz Liszt's Piano Transcriptions of "Sonetto 104 Del Petrarca"." (1997). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6648. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6648 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.