IC 75003 Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2003-Spring 2004)

David Korevaar, Helen and Peter Weil Professor of Piano 1 Updated: July 2018 David Korevaar University of Colorado at Boulder, College of Music 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301 303-492-6256, [email protected] www.davidkorevaar.com http://spot.colorado.edu/~korevaar Curriculum Vitae Educational Background: Doctor of Musical Arts, Piano, The Juilliard School, 2000. Doctoral Document: “Ravel’s Mirrors.” DMA Document. New York: The Juilliard School, 2000. xi + 196 pp. Awarded Richard French prize for best DMA Document, The Juilliard School, 2000. Committee: L. Michael Griffel, Robert Bailey, Jerome Lowenthal. Piano studies with Abbey Simon. Related area studies with Jonathan Dawe, Jane Gottlieb, L. Michael Griffel, David Hamilton, Joel Sachs, Maynard Solomon, Claudio Spies. Master of Music, Piano, The Juilliard School, 1983. Bachelor of Music, Piano, The Juilliard School, 1982. Piano studies with Earl Wild. Composition studies with David Diamond. Chamber music studies with Claus Adam, Paul Doktor, Felix Galimir, Leonard Rose, Harvey Shapiro. Independent piano studies: Paul Doguereau (1985-1998). Earl Wild (1976-1984). Sherman Storr (1969-1976). Andrew Watts (2013) Richard Goode (2013) Summer programs: Johannesen International School of the Arts, Victoria, B. C. (1980). Piano studies with John Ogdon, Robin McCabe, Joseph Bloch, Bela Siki. Bowdoin Summer Music Program (1981). Piano studies with Martin Canin. Aspen (1985). Piano studies with Claude Frank. David Korevaar, Helen and Peter Weil Professor of Piano 2 Teaching Affiliations: Academic year appointments: Current: Professor of Piano at the University of Colorado at Boulder (2011-); Associate Professor with tenure (2006-2011); appointed as Assistant Professor in 2000. Former: University of Bridgeport, Bridgeport, Connecticut (Adjunct position, “Head of Piano Studies”; 1995-2000). -

“War of the Romantics: Liszt and His Rivals” OCTOBER 24-27, 2019

2019 AMERICAN LISZT SOCIETY FESTIVAL “War of the Romantics: Liszt and his Rivals” OCTOBER 24-27, 2019 music.asu.edu AMERICAN LISZT SOCIETY www.americanlisztsociety.net A non-profit tax exempt organization under the provisions President of section Jay Hershberger 501 (c) (3) of Concordia College the Internal Music Department Revenue Moorhead, MN 56562 Code [email protected] Vice President Alexandre Dossin Greetings Dear Lisztians! University of Oregon School of Music & Dance Eugene, OR 97403-1225 On behalf of the board of directors of the American Liszt Society, it is an honor to welcome you to [email protected] the 2019 American Liszt Society Festival at the Arizona State University School of Music. We extend Executive/ Membership our gratitude to the Herberger Institute of Design and the Arts, Dr. Steven Tepper, Dean, to the School Secretary Justin Kolb of Music, Dr. Heather Landes, Director, and to our festival director, Dr. Baruch Meir, Associate Professor www.justinkolb.com 1136 Hog Mountain Road of Piano, for what promises to be a memorable and inspirational ALS festival. Dr. Meir has assembled Fleischmanns, NY 12430 a terrific roster of performers and scholars and the ALS is grateful for his artistic and executive oversight [email protected] of the festival events. Membership Secretary Alexander Djordjevic PO Box 1020 This year’s festival theme, War of the Romantics: Liszt and His Rivals brings together highly acclaimed Wheaton, IL 60187-1020 [email protected] guest artists, performances of important staples in the piano repertoire, a masterclass in the spirit of Liszt as creator of the format, informative lecture presentations, and a concert of choral masterpieces. -

Piano Transcriptions: Earl Wild's Virtuoso Etudes on Gershwin's Songs

Piano Transcriptions: Earl Wild's Virtuoso Etudes on Gershwin's Songs by Yun-Ling Hsu, D.M.A. Contact Email: [email protected] American pianist and composer Earl Wild (1915-2010) has been described as “one of the last in a long line of great virtuoso pianists/composers,” “one of the 20th century's greatest pianists, and “the finest transcriber of our time.” He transcribed seven George Gershwin’s popular songs: “1 Got Rhythm,” “Fascinating Rhythm,” “The Man I Love,” “Embraceable You,” “Oh, Lady, Be Good!,” “Liza,” and “Somebody Loves Me” as piano solo transcriptions entitled Seven Virtuoso Etudes. Because of my interest in the art of transcription, it has become my goal to discover more unique piano repertoire of transcription and reveal the nuances of the work in my practice and performance. While pursuing degrees in piano at the School of Music of The Ohio State University, I was extremely fortunate to study piano with Mr. Wild who was an Artist-In-Residence. In a faculty recital he performed three of his virtuoso etudes, “Liza,” “Somebody Loves Me,” and “I Got Rhythm.” These beautiful and clever etudes immediately drew my attention. Later I studied some of these etudes with him and performed in recitals over the years. The focus of this study is on the selected four of Earl Wild’s Seven Virtuoso Etudes- transcriptions based upon the following Gershwin’s songs: 1. “Embraceable You” 2. “The Man I Love” 3. “Fascinating Rhythm” 4. “I Got Rhythm” A brief overall transcriptional background, characteristics, a detailed examination of piano technique specifically on these four etudes, as well as a pre-recorded live performance can be heard at this YouTube link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LqxJALvcaf8 Background and Characteristics of the Transcriptions Besides concertizing, Wild was also interested in composing and transcribing. -

Earl Wild for the Full Listing Please Visit the Complete Transcriptions and Original Piano Works

ALSO AVAILABLE A selection of Piano Classics titles Earl Wild For the full listing please visit www.piano-classics.com The complete transcriptions and original piano works Earl Wild VOLUME 3 The complete transcriptions and original piano works VOLUME 1 Giovanni Doria Miglietta, piano PCL0069 PCL0102 PCL10155 PCL10174 PCL10182 PCL10183 Giovanni Doria Miglietta piano EARL WILD EARL WILD AND POPULAR MUSIC THE COMPLETE TRANSCRIPTIONS AND ORIGINAL PIANO WORKS, VOLUME 3 On a number of occasions Earl Wild has been compared to Franz Liszt, Frank Churchill 1901-1942/ Camille Saint-Saëns 1835-1921 /Wild and in 1986 (the centennial of Liszt’s death) Hungary awarded him a Liszt Earl Wild 1915-2010 3 Le Rouet d’Omphale, Op.31 9’18 Medal. They both dazzled their audiences with outstanding skills. They Reminiscences of Snow White 8’13 both were virtuoso performers of other composers’ music as well as 1 “Whistle While You Work” George Frideric Handel 1685-1759/ composers themselves of technically challenging piano pieces. Alongside “I’m Wishing” Wild their transcendental musicianship they shared a flair for showmanship “One Song” 4 Air and Variations – too. Liszt’s charisma and theatricality are well known (he used to open “Heigh-Ho” The Harmonious concerts by throwing his white gloves to the adoring audience). Earl “Someday My Prince Will Come” Blacksmith 4’26 Wild, from 1955 to 1957, was a regular guest in the Caesar’s Hour TV comedy show hosted by comedian/musician Sid Caesar, to which Mr. Wild George Gershwin 1898-1937/Wild Pyotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky 1840-1893/ contributed musical skits akin to those of the Grand Maestro of musical Fantasy on Porgy and Bess 29’21 Wild comedy, Victor Borge. -

An Examination of the Value of Score Alteration in Virtuosic Piano Repertoire

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 The Mutability of the Score: An Examination of the Value of Score Alteration in Virtuosic Piano Repertoire Wayne Weng The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3708 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE MUTABILITY OF THE SCORE: AN EXAMINATION OF THE VALUE OF SCORE ALTERATION IN VIRTUOSIC PIANO REPERTOIRE BY WAYNE WENG A dissertation suBmitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 WAYNE WENG ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii The Mutability of the Score: An Examination of the Value of Score Alteration in Virtuosic Piano Repertoire By Wayne Weng This manuscript has Been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Ursula Oppens ____________________ ____________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Norman Carey ____________________ ____________________________ Date Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Scott Burnham Raymond Erickson John Musto THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT The Mutability of the Score: An Examination of the Value of Score Alteration in Virtuosic Piano Repertoire by Wayne Weng Advisor: Scott Burnham This dissertation is a defense of the value of score alteration in virtuosic piano repertoire. -

Compact Disc M3234 2016 2-18.Pdf

PROGRAM Sonata in GMajor, Hob. 40 ..............9...:./.9.............................. FranzJoseph Haydn (1732·1809) I Allegretto innocente 2.. Presto Sonata in g minor, Opus 22 ..............?.~.!.. ~..Q...........................RobertSchumann (1810-1856) 3 Prestissimo 1: Andantino S- Scherzo <0 Presto Passionato INTERMISSION Virtuoso Etudes Based on Songs of George Gershwin ........ ~.?:.-...:..:.C?....... Earl Wild (1915-2010) 1- liza 8' Somebody Loves Me Cf I've Got Rhythm j 0 Lady, Be Good I ( Embraceable You {Z The Man I Love }3 Fascinating Rhythm ILf -01 C~: fV{.e Y\ae I ~ $(}h VI .. soYt 9 tJi'rt-UJr)T wtJYd 5/dve710 - 1; 4z 15 -&r1(o(e " OCv-ShlNln ..- IWifr-r:IWlfTv 111 Z- keJ> - n 13 NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Haydn: Sonata in GMajor, Hoboken 40 Haydn excelled in every musical genre. He is fondly known as lithe father ofthe symphony" and could with greaterjustice be thus regarded for the string quartet. No other composer approaches his combination ofproductivity, quality and historical importance for these genres. James Webster, The New Grove Haydn, 2002 The quantity of just aportion of Haydn's compositions, over 100 symphonies and over 60 piano sonatas, is staggering to contemplate when we realize that this is but afraction of his complete works! Haydn wrote with aluminOSity of intent and aclarity of craft which inspires us to this day. Part of his genius was the ability to develop large, sprawling structures out of very short motifs. Beethoven learned valuable lessons from this, for sure! The little GMajor sonata offered here, almost more of adivertimento, is aconsummate example ofthis masterful motivic manipulation. -

Wild About Wild: a Tribute to Earl Wild (1915-2010) & George Gershwin (1898-1937) with Earl Wild's Death on January 23, 2

Wild About Wild: A Tribute to Earl Wild (1915-2010) & George Gershwin (1898-1937) With Earl Wild’s death on January 23, 2010 at the age of 95, the world lost one of its legendary pianists, famous for his unique style that encompassed many influences both classical and popular. He will be remembered as one of the great interpreters of Liszt, Rachmaninoff, and most significantly, George Gershwin. Nor will his unmatchable piano technique be forgotten. This technique persisted through his 85th birthday recital at Carnegie Hall and to his final recital in February 2008, at the age of 95, in the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. His White House performances for six consecutive presidents, beginning with Herbert Hoover, also point to his long-standing reputation as a pianist and a personality. Not to be overlooked are Wild’s accomplishments as a composer. His Grand Fantasy on Porgy and Bess, his Seven Virtuoso Etudes, and his Improvisations on “Someone to Watch over Me,” all based on the music of George Gershwin, reveal his life-long interest in that American musical idol as well as his own compositional genius. Wild’s Piano Sonata (2000) sheds even more light on his remarkable abilities as a composer. Born on November 26, 1915, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Earl Wild began piano studies at the age of three. Before his twelfth birthday, he was accepted as a pupil of Selmar Janson, whose teachers were Xaver Scharwenka and Eugen d’Albert, a student of Franz Liszt. Mr. Wild went on to study with the great Dutch pianist, Egon Petri. -

RACHMANINOFF Earl Wild

RACHMANINOFF Earl Wild Chopin Variations, Op. 22 Corelli Variations, Op. 42 Preludes, Opp. 23 & 32 Sonata No. 2, Op. 36 Piano Transcriptions 2-CD Set RACHMANINOFF Earl Wild DISC I 1 Variations on a Theme of Chopin Op. 22 ..........................26:38 2 Variations on a Theme of Corelli Op. 42 ...........................17:40 3 Rimsky-Korsakov/Rachmaninoff The Flight of the Bumble-Bee ...........................................1:31 4 Mendelssohn/Rachmaninoff Scherzo from ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ ...........4:38 5 Kreisler/Rachmaninoff Liebesleid .....................................................................................5:21 TO T AL TIME : 55:14 - 2 - DISC II Sonata No. 2 in B-flat minor, Op. 36 Nine Preludes, Op. 32 1 Allegro agitato ................... 7:39 14 No. 1 in C Major .............. 1:13 2 Non allegro ........................ 6:18 15 No. 2 in D-flat Major ....... 2:56 3 Allegro molto..................... 5:55 16 No. 3 in E Major ............... 2:19 17 No. 4 in E minor............... 5:08 Ten Preludes, Op. 23 18 No. 5 in G Major .............. 2:49 4 No. 1 in F-sharp minor ... 3:24 19 No. 6 in F minor ............... 1:28 5 No. 2 in B-flat Major ....... 3:37 20 No. 7 in F Major ............... 2:16 6 No. 3 in D minor .............. 2:40 21 No. 8 in A minor .............. 1:41 7 No. 4 in D Major .............. 4:13 22 No. 10 in B minor ............ 2:40 8 No. 5 in G minor .............. 3:35 9 No. 6 in E-flat Major ....... 2:35 10 No. 7 in C minor .............. 2:22 11 No. 8 in A-flat Major ...... -

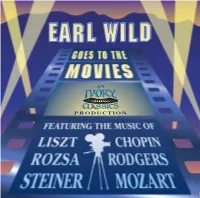

70801 for PDF 11/05

Earl Wild Goes To The Movies Music by Rodgers/Wild, Rózsa, Liszt, Chopin, Steiner, and Mozart Music on the screen can seek out and intensify the inner thoughts of the characters. It can invest a scene with terror, grandeur, gaiety or misery. It often lifts mere dialogue into the realm of poetry. It is the communicating link between screen and audience, reaching out and enveloping all into one single experience. — Bernard Herrmann Although it can be argued that music written for films serves a utilitarian or cos- metic role – largely as continuity or support of the visual – there is much film music that outlives the film it was written for. As the history of film has evolved, so has the history of film music. From the primitive days of pianistic improvisation for silent cinema to today’s extraordinary and complex scores, audiences have been regaled by musical creativity of astonishing proportions. Some of the greatest classical com- posers wrote film scores – Sergei Prokofiev, Ralph Vaughan Williams, William Walton, Dmitri Shostakovich, Aram Khachaturian, Arthur Honegger, Toru Takemitsu, Virgil Thomson, Darius Milhaud and Aaron Copland. Hollywood also created a sta- tus and prestige to film composing, generating a formidable group of musicians who are largely know today for their extraordinary cinematic scores. These include Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Alfred Newman, Franz Waxman, Dimitri Tiomkin, Bernard Herrmann, Alex North, Elmer Bernstein, Leonard Rosenman, Roy Webb, Max Steiner and Miklós Rózsa. In most cases, these composers lived a double life – their Hollywood or cinematic career, and their concert hall and stage career, creating music in both arenas. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 3 0 0 North Z eeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9014521 Twelve Rachmaninoff songs as transcribed for piano by Earl Wild: An introductory study Wu, Ching-Jen, D.M.A. -

2018 American Liszt Society Festival at Furman University, October 11

Founded in 1964 Volume 33, Number 2 2018 American Liszt Society Festival TABLE OF CONTENTS at Furman University, October 11 - 13 1 ALS Festival at Furman University Please join us for the 2018 American Liszt Society Festival and Conference. The Festival will take place October 11 - 13 on the campus of Furman University, Greenville, 2 President’s Message SC. The theme of this Festival is “The Poetic Liszt.” The Festival will focus on the exploration of the many aspects of poetry in Franz Liszt’s life and works. His enthusiasm for literature and poetry is openly reflected in the mottos and quotes Liszt 3 Letter from the Editor put in front of numerous works. But this is not where the affiliations end, and we can assume deeper connections between the art forms of literature and music, as represented 4 Los Angeles International Liszt by this erudite, cosmopolitan composer. These connections will function as a point Competition 2018, by Éva Polgár of departure from whence the Festival seeks to shed light on the many guises in which Liszt’s sensitivity to the written word appeared in his compositions. Membership Updates Highlights will include (subject to change): 5 My Ten Favorite Recordings of Liszt's Piano Music, by TedJ Distler • Epic tales • The complete early Album d’un voyageur To the Memory of a Giant • A special lecture on Chopin by Alan Walker • The Petrarch Sonnets (with and without words) 6 Resurrecting Liszt’s Sardanapalo, by • The rarely heard Melodramas David Trippett • Liszt organ encounters • And a lot more! In Memoriam: Reginald Gerig We are fortunate that “Fall for Greenville” weekend, a downtown food and music 7 Member News festival, will be happening the same weekend as the 2018 ALS Festival. -

Earl Wild Featuring the Gershwin Arrangements Xiayin Wang Earl Wild Wild Earl

The Piano Music of EARL WILD featuring the Gershwin arrangements Xiayin Wang Earl Wild © Mike Evans/Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Earl Wild (1915 –2010) Grand Fantasy on ‘Porgy and Bess’ (1976) 28:39 Based on themes from the opera by George Gershwin 1 Introduction – 0:15 2 Jasbo Brown Blues – 1:46 3 Summertime – 2:59 4 Oh, I can’t sit down – 1:32 5 My man’s gone now – 3:10 6 I got plenty o’ nuttin’ – 3:07 7 Buzzard Song – 2:35 8 It ain’t necessarily so – 4:06 9 Bess, you is my woman now – 2:45 10 I loves you, Porgy/Bess, you is my woman now – 2:06 11 There’s a boat dat’s leavin’ soon for New York – 2:46 12 Oh Lawd, I’m on my way 1:27 Seven Virtuoso Études (1976) 20:32 Based on songs by George Gershwin 13 1 Liza 3:42 14 2 Somebody loves me 3:03 15 3 The man I love 2:25 3 16 4 Embraceable you 3:05 17 5 Oh, lady, be good! 4:18 18 6 I got rhythm 2:15 19 7 Fascinating rhythm 1:39 Improvisation on ‘Someone to Watch over Me’ (1990) 12:31 in the form of a theme and three variations on the song by George Gershwin 20 Theme 3:12 21 Barcarolle 2:31 22 Brazilian Dance 2:31 23 Tango 4:14 Piano Sonata (2000) 17:16 24 I Allegro (March) 6:12 25 II Adagio 6:39 26 III Toccata (à la Ricky Martin) 4:22 TT 79:13 Xiayin Wang piano 4 Wild about Wild: A Tribute to Earl Wild and George Gershwin Introduction His Piano Sonata sheds further light on his With the death of Earl Wild on 23 January remarkable abilities as a composer.