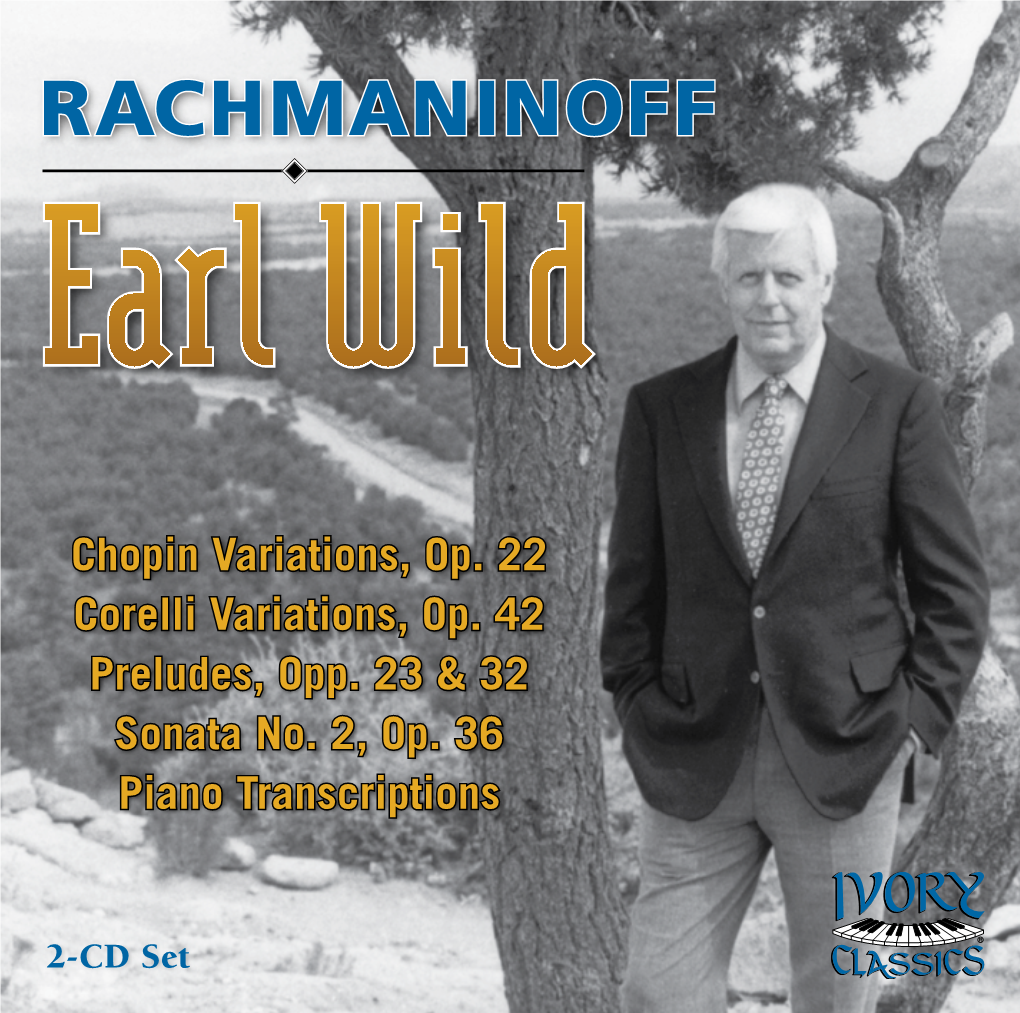

RACHMANINOFF Earl Wild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (Guest Post)*

The Complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas--Artur Schnabel (1932-1935) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by James Irsay (guest post)* Artur Schnabel Austrian pianist Artur Schnabel has been called “the man who invented Beethoven”... a strange thing to say considering Schnabel was born more than half a century after Beethoven, universally recognized as the greatest composer in Europe, died in 1827. What, then, did Artur Schnabel invent? The 32 piano sonatas of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) represent one of the great artistic achievements in human history, and stand as the musical autobiography of the great composer's maturity, from his 25th until his 53rd year, four years before his death. The fruit of those years mark a staggering creative journey that began and ended in the composer's adopted home of Vienna, “Music Central” to the German-speaking world. Beethoven's musical path led from the domain of Haydn and Mozart to the world of his late period, when the agonizing progress of his deafness had become complete. By then, Beethoven's musical narrative had begun to speak a new language, proceeding according to a new logic that left many listeners behind. While the beauties of his music and his deep genius were generally recognized, at the same time, it was thought by some critics that Beethoven frequently smudged things up with his overly- bold, unfettered invention, even well before his final period: Beethoven, who is often bizarre and baroque, takes at times the majestic flight of an eagle, and then creeps in rocky pathways. He first fills the soul with sweet melancholy, and then shatters it by a mass of shattered chords. -

Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme By

RACHMANINOFF’S RHAPSODY ON A THEME BY PAGANINI, OP. 43: ANALYSIS AND DISCOURSE Heejung Kang, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor and Program Coordinator Stephen Slottow, Minor Professor Josef Banowetz, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Interim Chair of Piano Jessie Eschbach, Chair of Keyboard Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrill, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kang, Heejung, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43: Analysis and Discourse. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2004, 169 pp., 40 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 39 titles. This dissertation on Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43 is divided into four parts: 1) historical background and the state of the sources, 2) analysis, 3) semantic issues related to analysis (discourse), and 4) performance and analysis. The analytical study, which constitutes the main body of this research, demonstrates how Rachmaninoff organically produces the variations in relation to the theme, designs the large-scale tonal and formal organization, and unifies the theme and variations as a whole. The selected analytical approach is linear in orientation - that is, Schenkerian. In the course of the analysis, close attention is paid to motivic detail; the analytical chapter carefully examines how the tonal structure and motivic elements in the theme are transformed, repeated, concealed, and expanded throughout the variations. As documented by a study of the manuscripts, the analysis also facilitates insight into the genesis and structure of the Rhapsody. -

2017-2018 Master Class-Leon Fleisher

Welcome to the 2017-2018 season. The talented students and extraordinary faculty of the Lynn LEON FLEISHER MASTER CLASS Conservatory of Music take this opportunity to share with you the beautiful world of music. Your Wednesday, January 24, 2018 at 7:00 pm ongoing support ensures our place among the premier conservatories Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall of the world and a staple of our community. - Jon Robertson, dean PROGRAM There are a number of ways by which you can help us fulfill our mission: Friends of the Conservatory of Music Sonata Op. 2 No. 2 in A Major Ludwig van Beethoven Lynn University’s Friends of the Conservatory of Music is a IV Rondo: Grazioso (1770-1827) volunteer organization that supports high-quality music education through fundraising and community outreach. Raising more than $2 million since 2003, the Friends support Lynn’s effort to provide Chance Israel, piano free tuition scholarships and room and board to all Conservatory of Music students. The group also raises money for the Dean’s Discretionary Fund, which supports the immediate needs of the university’s music performance students. This is accomplished through annual gifts and special events, such as outreach concerts and the annual Gingerbread Holiday Concert. To learn more about joining the Friends and its many benefits, Scherzo No. 4 in E Major Frederic Chopin such as complimentary concert admission, visit Give.lynn.edu/support-music. (1810-1849) The Leadership Society of Lynn University Meiyu Wu, piano The Leadership Society is the premier annual giving society for donors who are committed to ensuring a standard of excellence at Lynn for all students. -

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

A/L CHOPIN's MAZURKA

17, ~A/l CHOPIN'S MAZURKA: A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS OF J. S. BACH--F. BUSONI, D. SCARLATTI, W. A. MOZART, L. V. BEETHOVEN, F. SCHUBERT, F. CHOPIN, M. RAVEL AND K. SZYMANOWSKI DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial. Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By Jan Bogdan Drath Denton, Texas August, 1969 (Z Jan Bogdan Drath 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . I PERFORMANCE PROGRAMS First Recital . , , . ., * * 4 Second Recital. 8 Solo and Chamber Music Recital. 11 Lecture-Recital: "Chopin's Mazurka" . 14 List of Illustrations Text of the Lecture Bibliography TAPED RECORDINGS OF PERFORMANCES . Enclosed iii INTRODUCTION This dissertation consists of four programs: one lec- ture-recital, two recitals for piano solo, and one (the Schubert program) in combination with other instruments. The repertoire of the complete series of concerts was chosen with the intention of demonstrating the ability of the per- former to project music of various types and composed in different periods. The first program featured two complete sets of Concert Etudes, showing how a nineteenth-century composer (Chopin) and a twentieth-century composer (Szymanowski) solved the problem of assimilating typical pianistic patterns of their respective eras in short musical forms, These selections are preceded on the program by a group of compositions, consis- ting of a. a Chaconne for violin solo by J. S. Bach, an eighteenth-century composer, as. transcribed for piano by a twentieth-century composer, who recreated this piece, using all the possibilities of modern piano technique, b. -

The Elgar Sketch-Books

THE ELGAR SKETCH-BOOKS PAMELA WILLETTS A MAJOR gift from Mrs H. S. Wohlfeld of sketch-books and other manuscripts of Sir Edward Elgar was received by the British Library in 1984. The sketch-books consist of five early books dating from 1878 to 1882, a small book from the late 1880s, a series of eight volumes made to Elgar's instructions in 1901, and two later books commenced in Italy in 1909.^ The collection is now numbered Add. MSS. 63146-63166 (see Appendix). The five early sketch-books are oblong books in brown paper covers. They were apparently home-made from double sheets of music-paper, probably obtained from the stock of the Elgar shop at 10 High Street, Worcester. The paper was sewn together by whatever means was at hand; volume III is held together by a gut violin string. The covers were made by the expedient of sticking brown paper of varying shades and textures to the first and last leaves of music-paper and over the spine. Book V is of slightly smaller oblong format and the sides of the music sheets in this volume have been inexpertly trimmed. The volumes bear Elgar's numbering T to 'V on the covers, his signature, and a date, perhaps that ofthe first entry in the volumes. The respective dates are: 21 May 1878(1), 13 August 1878 (II), I October 1878 (III), 7 April 1879 (IV), and i September 1881 (V). Elgar was not quite twenty-one when the first of these books was dated. Earlier music manuscripts from his hand have survived but the particular interest of these early sketch- books is in their intimate connection with the round of Elgar's musical activities, amateur and professional, at a formative stage in his career. -

Thejoy That Comes with Music

(I Jnfernafionaf JlJRJ8Jl SEND IN YOUR SUGGESTIONS FOR RECUTTING BY NICK JARRETT Mieczyslaw Manz, 75, Is Dead; I know many of us have a pet roll or rolls we would A Concert Pianist and Teacher like to see recut. I took this matter up with . Mieczyslaw Munz, a fonner major, the Brahms concerto in Elwood Hansen, owner of the plant at Turlock. He concert pianist who appeared D minor and the Franck Sym assured me that there is no exclusive contract to ~ith many of the.world's lead- phonic Variations. prevent such a project, and suggested that I might 109 orchestras, di~ yesterday Mr Munz made his solo of a heart attack 10 an ambu-' . co-ordinate requests from the membership. Please lance as he was being taken to debut at Aeoli:an, Hall 10 New write and let me know what ~ would like. hospital from his home at the York on Oct. 20, 1922. The Ten Park Avenue Hotel. He New York Times review called was 75 years old. him "an absorbed artist, under It has been suggested that special attention be Mr. Munz, who taught at the whose hands mere tricks and given to the type of rolls that seldom appear on Juilliard School for 12 years, graces of piano playm'.. fall was scheduled to return to the . • lists of recuts: PIANO music played by the great Juilliard School next month, away as chips from the sculp- artists of the reproducing piano's heyday. This is after a sabbatical year of teach- tor's chisel, wbliIe he lays ~are iing at Giebel University in the larger curves of sustamed not an attempt to put AMR or Klavier out of business, Tokyo. -

Swan Lake Takes out the Classic 100: Dance Countdown

10 JUNE 2018 – EMBARGOED UNTIL 19:01 AEST-- Swan Lake takes out the Classic 100: Dance Countdown Swan Lake has been named Australia’s favourite classical dance music in ABC Classic FM’s Classic 100 Countdown. Australia’s favourite classical music event has celebrated the brilliant diversity, vivid colour and irresistible impulse of dance, by counting down the music that makes its audiences move. Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, one of the world’s most beloved ballets, tells the story of Odette, a princess transformed into a swan by the curse of an evil sorcerer. Australia’s passionate community of music lovers voted in their thousands in the annual campaign by ABC Classic FM, our only national classical music station. Nearly 2000 works were reduced by public voting to the final 100 broadcast this weekend. More than 50% of the performers featured in this flagship event are Australian, exemplifying the ABC’s crucial role in nurturing local talent. ABC Classic FM is dedicated to investing in high-quality and distinctive Australian music and performance, free for all Australians. ABC Classic FM has collaborated with The Australian Ballet to produce three films specifically for the Countdown. Emerging choreographers Alice Topp, Richard House and Ella Havelka created striking new responses to the top three featured works: Swan Lake, The Nutcracker Suite, and Romeo and Juliet. Why Dance, a 3 x 20 minute feature series from the ABC’s Dr Ann Jones, has launched on air on ABC Classic FM, online and on the ABC listen app to mark this year’s theme. In association with The Australian Ballet, Sydney Dance Company and Bangarra Dance Theatre, Ann explores female choreographers in the male- dominated world of ballet, the importance of dance in Indigenous culture, and the healing role of dance in the lives of some everyday Australians. -

Music for Viola and Piano, September 30, 2018 Lawrence University

Lawrence University Lux Conservatory of Music Concert Programs Conservatory of Music 9-30-2018 12:00 AM Music for Viola and Piano, September 30, 2018 Lawrence University Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/concertprograms Part of the Music Performance Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Lawrence University, "Music for Viola and Piano, September 30, 2018" (2018). Conservatory of Music Concert Programs. Program 311. https://lux.lawrence.edu/concertprograms/311 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Conservatory of Music at Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Conservatory of Music Concert Programs by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guest Recital Music for Viola and Piano Sheila Browne, viola Julie Nishimura, piano Sunday, September 30, 2018 6:00 p.m. Harper Hall Sonatensatz from the F-A-E Sonata, WoO posth. 2 Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Sonata for Viola and Piano (1979) George Rochberg Allegro moderato (1918-2005) Adagio lamentoso Fantasia: Epilogue INTERMISSION Convergence (2009) Andrea Clearfield (b. 1960) Sonata for Viola and Piano (1919) Rebecca Clarke Impetuoso (1886-1979) Vivace Adagio PERFORMER BIOS Hailed by the New York Times as a “stylish player” for a concerto performance in Carnegie Hall’s Stern Auditorium, violist Sheila Browne is an accomplished international soloist, chamber musician and professor. Honored to be named the William Primrose Memorial Recitalist of 2016, Ms. Browne has performed in major halls on six continents, including solo performances with the Juilliard Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, New World Symphony, in Carnegie Hall with the New York Women’s Ensemble, South African International Viola Congress Festival Orchestra, and the Viva Vivaldi!, Reina Sofia and German French chamber orchestras, and with the Highland Mountain Correctional Center Women’s String Orchestra in Alaska. -

Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 TARAL WAYNE :: NIALL Mcgrath & TIM TRAIN :: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) :: BRUCE GILLESPIE :: ABC CLASSICS Top 100 Scratch Pad 77 March 2011

Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 TARAL WAYNE :: NIALL McGRATH & TIM TRAIN :: DITMAR (DICK JENSSEN) :: BRUCE GILLESPIE :: ABC CLASSICS Top 100 Scratch Pad 77 March 2011 Based on the non-mailing comments section of *brg* 67 and 68, a fanzine for ANZAPA (Australia and New Zealand Amateur Publishing Association) written and published by Bruce Gillespie, 5 Howard St, Greensborough VIC 3088. Phone: (03) 9435 7786. Email: [email protected]. Member fwa. Website: GillespieCochrane.com.au Contents 3 Unsolved mysteries of the hereafter — by Taral Wayne 6 The brand new Scratch Pad poetry spot — by Niall McGrath and Tim Train 9 Ditmar’s best and favourite films of 2010 — by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) 15 Shining shores: Bruce Gillespie’s favourites 2010 — by Bruce Gillespie 36 ABC Classic 100 ten years on: 2010 — introduced by Bruce Gillespie Cover graphic — ‘Evening Phenomenon’ by Ditmar (Dick Jenssen) Cartoon p. 3: ‘Unsolved mysteries’ — by Taral Wayne 2 Unsolved mysteries of the hereafter by Taral Wayne I think some scholar, or someone who wanted to be mistaken for one, claimed that the translation from the Koran was wrong, and it wasn’t ‘seventy virgins’, but something like ‘seventy figs’, that a good Muslim could expect in Paradise, and that it only meant the blessed would be in the midst of plenty. I’m not sure I buy that. It was only 1500 years ago, and I don’t think Arabic then was so different from modern Arabic that millions of Arab Muslims make such an elementary mistake. But who knows ... maybe Allah really only did mean that the nearly arrived would be greeted with a plate of figs ..