The Pianist's Freedom and the Work's Constrictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Firlngllne Copyright University

rights other a All infringement. makes resale. for user a copyright not If for are liable material. be Copies may 94305-6010 user copyrighted prohibited. CA of is that use, New FIRlnGLlne This Transcripts 29205 HOST GUESTS FIRING Stanford, SUBJECT fair distribution of is reproductions York 8031799-3449 : a and further transcript LINE excess University, : other videocassettes : City in or and is , March "IS WILLIAM Stanford produced material. ROSALYN of reprints purposes a re GOOD this FIRING available for photocopies of 31, of Archives, and 1999, additional MUSIC through copies) re-use and Copyright F. LINE TURECK making directed BUCKLEY, any and Producers the Library program purposes; GOING telecast 1999 before handwritten by Inc and governs o FIRING WARREN rporated Institution owner SCHUYLER #2833/1200, UNDER?" JR. later educational Code) (including fo LINE and Hoover r on Television, U.S. copyright public University. 17, STEIBEL. the Jr. Director, taped CHAPIN reproduction 2700 (Title from television or Cypress Stanford contact at non-commercial, States HBO Street, permission photocopy Leland stations United private, a Columbia, Studios the for the obtain information, of is uses of to . SC later laws further in or material Trustees advised For of for, this are of copyright ©Board reserved. Users Use The request © Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. MR. BUCKLEY: Every few years Firing Line touches down on the question, Is classical music dying? We are lucky enough this time around to have got in to discuss the question two persons who have spoken to us before on the subject. One is perhaps the most distinguished pianist alive, the second, the senior man of music in New York City. -

Fri, Aug 20, 2021

Fri, Aug 20, 2021 - 09 Listener Requests on The Classical Station 1 Start Description Performers Requested by Additional 09:01:10 Overture to Candide / Bernstein Bournemouth Symphony/Litton Carol in Fuquay-Varina 09:06:32 Grand Canyon Suite / Grofé London Philharmonic George in Raleigh Orchestra/Handley 09:40:50 Rider March in C, D. 866 No. 1 / Vienna Academy Cathy in Menominee Falls, Schubert Orchestra/Haselbock Wisc. 09:51:27 Romance for String Orchestra, Op. 11 / Northern Sinfonia/Griffiths Vincent in Greensboro, Finzi NC 10:01:30 Radetzky March / Strauss Sr. Johann Strauss Orchestra Timothy in Rocky Mount, Vienna/Francek NC 10:05:38 Nuvole bianche / Einaudi Ludovico Einaudi Rachel in Raleigh 10:13:03 Suite Bergamasque / Debussy Alexis Weissenberg Kenneth in Apex, NC also for Linda in Whitewater, Wisc. 10:29:23 Piano Quintet in E flat, Op. 44 / Robert Schumann Ensemble Vivian in Carrboro, NC Schumann 11:00:20 Suite for Flute and Strings / Respighi Fabbriciani/Abruzzo Adrienne in Raleigh Symphony/Paszkowski 11:21:15 Eclogue for Piano and Strings / Finzi Jones/English String Cyndi in Raleigh Orchestra/Boughton 11:32:28 The Girl with the Flaxen Hair from Samson Francois Greg in Ronkonkoma, NY in memory of his Preludes, Book I / Debussy beloved wife, Carol 11:35:53 Partita No. 2 in C minor, BWV 826 / Simone Dinnerstein Desiree in Coconut Creek, Bach Fla. 12:00:25 Concerto in B minor for 4 Violins and English Concert/Pinnock Rhowan in Garner, NC Cello, Op. 3 No. 10 / Vivaldi 12:10:50 Recuerdos de la Alhambra / Tarrega David Russell Lynn in Durham, NC 12:17:30 Finlandia, Op. -

David Dubal Tem Dado Recitais De Piano E Masterclasses Em Todo O

David Dubal tem dado recitais de piano e masterclasses em todo o mundo, e foi jurado de competições internacionais de piano (incluindo o Van Cliburn International Piano Competition). Ele gravou vários CDs em conjunto com o pianista Stanley Waldoff para a gravadora Musical Heritage Society, e três discos foram remasterizados e lançados em CD pela gravadora Arkiv. Em 2013, Dubal participou do filme Holandês Nostalgia: a Música de Wim Statius Müller, comentando sobre as músicas do compositor, o qual foi seu professor em Ohio. Dubal lecionou na Juilliard School de 1983 a 2018, e na Manhattan School of Music de 1994 a 2015. Dubal escreveu vários livros, incluindo a Arte do Piano, Noites com Horowitz, Conversas com Menuhin, Reflexões do Teclado, Conversas com João Carlos Martins, Lembrando Horowitz e O Essencial Cânone da Música Clássica (um guia enciclopédico dos compositores proeminentes). Ele também escreveu e apresentou o documentário A Era Dourada do Piano, premiado com um Emmy e produzido por Peter Rosen. Dubal dá palestras semanais, Noites com Piano, na Good Shepherd-Faith Presbyterian Church, em Nova Iorque. Ele deu inúmeras palestras no Metropolitan Museum of Art sobre os grandes pianistas, mudanças sociais, história da música e tradição do piano. Suas palestras estão disponíveis em seu site: https://www.pianoevenings.com/david-dubal. Dubal é o anfitrião das palestras Sobre o Piano, um programa de performances comparativas de piano na WWFM e o anfitrião de Reflexões do Teclado, uma exploração semanal de gravações de piano, produzido na WQXR-FM. No final da década de 1990, ele apresentou uma série de programas de rádio intitulado The American Century, com foco em obras musicais de compositores Americanos do século XX, agora disponíveis no YouTube. -

Sat Oct 5 Program Notes

PROGRAM NOTES: SAT / OCT 5 By Bill Crane, Director of Audience Engagement, Portland Piano International “When it comes to translating human emotions, the piano is the most perfect instrument I know.” – Marc-André Hamelin in his recent interview for BBC Music Magazine Whether as listener, student, teacher, composer, or performer, one has so many ways to approach the seemingly endlessly varied sonorities of the piano, ripe for expressing myriad emotions. As well, the piano allows a single performer to create such abundance of music – with such satisfying results, when in good hands – that composers for it have stretched its capacities tirelessly, always exploring possibilities. We live in a time well after all constraints of harmonic and formal practice that characterized music before the “modern” period were thrown off. Much of the music after the end of the 19th century, indeed, was quite reflective of the tumultuous times in which the Western world lived with boundless conflict and astounding change. This is particularly true, of course, of the Russian piano tradition, from which we will hear stellar examples in these recitals, but not there only. French music comes to mind, of course, with its own special harmonic innovations and suave, evocative ways. You are about to encounter bazillions of notes, more than seems humanly possible. More important, though, you are in for sublime artistry. This swirling world of music and musical ideas borne of many profound influences, some directly “artistic” and some esoteric (spiritual matters, political intrigue, lovers’ longing and laments), some clear to understand and others distinctly not so. I would bet that a majority of the pieces found in these two programs will be new to you, as they were to me. -

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

Paul Jacobs, Elliott Carter, and an Overview of Selected Stylistic Aspects of Night Fantasies

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2016 Paul Jacobs, Elliott aC rter, And An Overview Of Selected Stylistic Aspects Of Night Fantasies Alan Michael Rudell University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Rudell, A. M.(2016). Paul Jacobs, Elliott aC rter, And An Overview Of Selected Stylistic Aspects Of Night Fantasies. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3977 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAUL JACOBS, ELLIOTT CARTER, AND AN OVERVIEW OF SELECTED STYLISTIC ASPECTS OF NIGHT FANTASIES by Alan Michael Rudell Bachelor of Music University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2004 Master of Music University of South Carolina, 2009 _____________________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Joseph Rackers, Major Professor Charles L. Fugo, Committee Member J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Marina Lomazov, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Alan Michael Rudell, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my thanks to the members of my committee, especially Joseph Rackers, who served as director, Charles L. Fugo, for his meticulous editing, J. Daniel Jenkins, who clarified certain issues pertaining to Carter’s style, and Marina Lomazov, for her unwavering support. -

Degaetano CONCERTO NO. 1 CHOPIN

RobertDeGAETANO CONCERTO DeGaetano NO. 1 CHOPIN CONCERTO NO. 1 Because of my lack of experience as a composer I didn’t realize The Saga of Piano Concerto No. 1 how much was involved in such an undertaking or what the costs would be. BY ROBERT DeGAETANO I quickly started writing away. The music came very quickly. My first piano concerto began many years ago. I heard a theme I felt like I was a conduit and it poured right through me. that I knew was mine. At the time I had just begun composing seriously and I was instantly aware that this theme was for a A performance date and rehearsal was arranged with Stephen major work, either a concerto or symphony. It was grand in Osmond, conductor of the Jackson Symphony and we were off design and had a monumental quality. This was not a melody and running. I mean literally running! I believe I had less than three to be used in a shorter work. I remember jotting it down and months from the date of the commission to the actual premier. storing it with my manuscript paper. Fortunately I had a little cabin in the northern Catskills of NY where I was able to concentrate freely. In 1986 I gave a concert in “ The music came New York and premiered After completing the piano part and a general sketch of the my first piano Sonata very quickly. I felt orchestration, I set forth on the orchestration. I also had to deal dedicated to my maternal with getting the work copied legibly from the original score. -

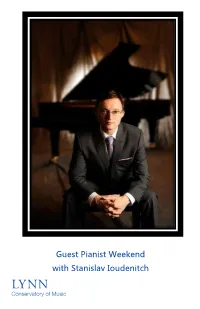

2016-2017 Master Class-Stanislav Ioudenitch

Guest Pianist Weekend with Stanislav Ioudenitch Pianist Stanislav Ioudenitch In Recital Saturday, Dec. 3 7:30 p.m. Count and Countess de Hoernle International Center Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall PROGRAM Spanish Rhapsody Franz Liszt Partita No. 2 in C minor JS Bach Sinfonia Allemande Courante Sarabande Rondeaux Capriccio Moment Musicaux Franz Schubert No. 3 Allegro moderato in F minor No. 4 Moderato in C-sharp minor Sonata No. 2 (1913 edition) Sergei Rachmaninoff Allegro agitato Non allegro Allegro molto Artist Biography STANISLAV IOUDENITCH has garnered notable successes in music competitions including the Gold Medal at the XI Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2001. The Van Cliburn Competition launched a career that has taken Ioudenitch around the world for appearances with major venues, including Carnegie Hall, the Kennedy Center, Fort the Moscow Conservatoire, Mariinsky Concert Hall, the Great Hall of the St Petersburg Philharmonic, the Conservatorio Giuseppe Verdi in Milan, the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, the Oriental Art Center in Shanghai and appeared at major festivals including the International Piano Festival in the United States and the Ruhr Music Festival in Germany among others. Ioudenitch has collaborated with a wide range of international conductors including James Conlon, Valery Gergiev, Mikhail Pletnev, Asher Fisch, Vladimir Spivakov, Günther Herbig, Pavel Kogan, James DePreist, Michael Stern, Stefan Sanderling, Carl St. Clair and Justus Frantz, and with such orchestras as the National Symphony in Washington DC, the Munich Philharmonic, Mariinsky Orchestra, the Rochester Philharmonic, the National Philharmonic of Russia, the Fort Worth Symphony and the Kansas City Symphony among others. He has also performed with the Takács, Prazák and Borromeo String Quartets and is a founding member of the Park Piano Trio. -

2016 Program Booklet

Rebecca Penneys Piano Festival Fourth Year July 12 – 30, 2016 University of South Florida, School of Music 4202 East Fowler Avenue, Tampa, FL The family of Steinway pianos at USF was made possible by the kind assistance of the Music Gallery in Clearwater, Florida Rebecca Penneys Ray Gottlieb, O.D., Ph.D President & Artistic Director Vice President Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano wishes to give special thanks to: The University of South Florida for such warm hospitality, USF administration and staff for wonderful support and assistance, Glenn Suyker, Notable Works Inc., for piano tuning and maintenance, Christy Sallee and Emily Macias, for photos and video of each special moment, and All the devoted piano lovers, volunteers, and donors who make RPPF possible. The Rebecca Penneys Piano Festival is tuition-free for all students. It is supported entirely by charitable tax-deductible gifts made to Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano Incorporated, a non-profit 501(c)(3). Your gifts build our future. Donate on-line: http://rebeccapenneyspianofestival.org/ Mail a check: Rebecca Penneys Friends of Piano P.O. Box 66054 St Pete Beach, Florida 33736 Become an RPPF volunteer, partner, or sponsor Email: [email protected] 2 FACULTY PHOTOS Seán Duggan Tannis Gibson Christopher Eunmi Ko Harding Yong Hi Moon Roberta Rust Thomas Omri Shimron Schumacher D mitri Shteinberg Richard Shuster Mayron Tsong Blanca Uribe Benjamin Warsaw Tabitha Columbare Yueun Kim Kevin Wu Head Coordinator Assistant Assistant 3 STUDENT PHOTOS (CONTINUED ON P. 51) Rolando Mijung Hannah Matthew Alejandro An Bossner Calderon Haewon David Natalie David Cho Cordóba-Hernández Doughty Furney David Oksana Noah Hsiu-Jung Gatchel Germain Hardaway Hou Jingning Minhee Jinsung Jason Renny Huang Kang Kim Kim Ko 4 CALENDAR OF EVENTS University of South Florida – School of Music Concerts and Masterclasses are FREE and open to the public Donations accepted at the door Festival Soirée Concerts – Barness Recital Hall, see p. -

Bach's Goldberg Variations

Bach’s Goldberg Variations - A survey of the piano recordings by Ralph Moore Let me say right away that while I am well aware that Bach specified on the title page that these variations are for harpsichord, I much prefer them played on the modern piano in what is technically a transcription and venture to suggest that Bach would have loved the sonorities and flexibility of the modern instrument, even though it inevitably involves essentially faking the changes of register available on a double manual harpsichord. I hardly seem to be alone in this, in that, just as every great cellist wants to engage with the Cello Suites, so almost every great pianist seems to want to record his or her interpretation of the Goldbergs for posterity and the public appetite for recordings and performances on the pianoforte seems undiminished. I have accordingly confined this survey to that category; doubtless more authentic accounts on an original instrument have great merit but they lie beyond my scope, knowledge and experience; I have neither the acquaintance with, nor appreciation for, harpsichord versions to attempt a meaningful conspectus of them; nor, indeed, do I have the recording on my shelves and leave that task to a better-qualified reviewer. Here, however, is a good collective survey of the harpsichord recordings from The Classic Review aimed at the average punter like me. In common with many a devotee of this miraculous music, my own first encounter with it was via the second Glenn Gould recording when, many years ago, a cultivated girlfriend introduced me to it; it was love at first hearing (assisted, perhaps by my attachment to said lady, but that’s another story…). -

Fifty-Seventh National Conference October 30–November 1, 2014 Ritz Carlton St

Fifty-Seventh National Conference October 30–November 1, 2014 Ritz Carlton St. Louis St. Louis, Missouri PRESENTER & COMPOSER BIOS updated October 25, 2014 Abeles, Harold F. Dr. Harold Abeles is a Professor of Music and Music Education at Teachers College, Columbia University, where he also serves as Co-Director of the Center for Arts Education Research. He has contributed numerous articles, chapters and books to the field of music education. He is the co-author of the Foundations of Music Education and the co-editor, with Professor Lori Custodero, of Critical Issues in Music Education: Contemporary Theory and Practice. Recent chapters by him have appeared in the Handbook of Music Psychology and the New Handbook of Research on Music Teaching and Learning. He was the founding editor of The Music Researchers Exchange, an international music research newsletter begun in 1974. He served as a member of the Executive Committee of the Society for Research in Music Education and has served on the editorial boards of several journals including the Journal of Research in Music Education, Psychomusicology, Dialogue in Instrumental Music Education, Update, and Arts Education Policy Review. His research has focused on a variety of topics including, the evaluation of community-based arts organizations, the assessment of instrumental instruction, the sex- stereotyping of music instruments, the evaluation of applied music instructors, the evaluation of ensemble directors, technology-based music instruction, and verbal communication in studio instruction. Adler, Ayden With a background as a performer, writer, teacher, and administrator, Ayden Adler serves as Senior Vice President and Dean at the New World Symphony, America’s Orchestral Academy. -

Digital Concert Hall Where We Play Just for You

www.digital-concert-hall.com DIGITAL CONCERT HALL WHERE WE PLAY JUST FOR YOU PROGRAMME 2016/2017 Streaming Partner TRUE-TO-LIFE SOUND THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL AND INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN In the Digital Concert Hall, fast online access is com- Internet Initiative Japan Inc. is one of the world’s lea- bined with uncompromisingly high quality. Together ding service providers of high-resolution data stream- with its new streaming partner, Internet Initiative Japan ing. With its expertise and its excellent network Inc., these standards will also be maintained in the infrastructure, the company is an ideal partner to pro- future. The first joint project is a high-resolution audio vide online audiences with the best possible access platform which will allow music from the Berliner Phil- to the music of the Berliner Philharmoniker. harmoniker Recordings label to be played in studio quality in the Digital Concert Hall: as vivid and authen- www.digital-concert-hall.com tic as in real life. www.iij.ad.jp/en PROGRAMME 2016/2017 1 WELCOME TO THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL In the Digital Concert Hall, you always have Another highlight is a guest appearance the best seat in the house: seven days a by Kirill Petrenko, chief conductor designate week, twenty-four hours a day. Our archive of the Berliner Philharmoniker, with Mozart’s holds over 1,000 works from all musical eras “Haffner” Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s for you to watch – from five decades of con- “Pathétique”. Opera fans are also catered for certs, from the Karajan era to today. when Simon Rattle presents concert perfor- mances of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre and The live broadcasts of the 2016/2017 Puccini’s Tosca.