Sat Oct 5 Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fri, Aug 20, 2021

Fri, Aug 20, 2021 - 09 Listener Requests on The Classical Station 1 Start Description Performers Requested by Additional 09:01:10 Overture to Candide / Bernstein Bournemouth Symphony/Litton Carol in Fuquay-Varina 09:06:32 Grand Canyon Suite / Grofé London Philharmonic George in Raleigh Orchestra/Handley 09:40:50 Rider March in C, D. 866 No. 1 / Vienna Academy Cathy in Menominee Falls, Schubert Orchestra/Haselbock Wisc. 09:51:27 Romance for String Orchestra, Op. 11 / Northern Sinfonia/Griffiths Vincent in Greensboro, Finzi NC 10:01:30 Radetzky March / Strauss Sr. Johann Strauss Orchestra Timothy in Rocky Mount, Vienna/Francek NC 10:05:38 Nuvole bianche / Einaudi Ludovico Einaudi Rachel in Raleigh 10:13:03 Suite Bergamasque / Debussy Alexis Weissenberg Kenneth in Apex, NC also for Linda in Whitewater, Wisc. 10:29:23 Piano Quintet in E flat, Op. 44 / Robert Schumann Ensemble Vivian in Carrboro, NC Schumann 11:00:20 Suite for Flute and Strings / Respighi Fabbriciani/Abruzzo Adrienne in Raleigh Symphony/Paszkowski 11:21:15 Eclogue for Piano and Strings / Finzi Jones/English String Cyndi in Raleigh Orchestra/Boughton 11:32:28 The Girl with the Flaxen Hair from Samson Francois Greg in Ronkonkoma, NY in memory of his Preludes, Book I / Debussy beloved wife, Carol 11:35:53 Partita No. 2 in C minor, BWV 826 / Simone Dinnerstein Desiree in Coconut Creek, Bach Fla. 12:00:25 Concerto in B minor for 4 Violins and English Concert/Pinnock Rhowan in Garner, NC Cello, Op. 3 No. 10 / Vivaldi 12:10:50 Recuerdos de la Alhambra / Tarrega David Russell Lynn in Durham, NC 12:17:30 Finlandia, Op. -

The Pianist's Freedom and the Work's Constrictions

The Pianist’s Freedom and the Work’s Constrictions What Tempo Fluctuation in Bach and Chopin Indicate Alisa Yuko Bernhard A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Alisa Yuko Bernhard 10 November 2016 i Abstract The concept of the musical work has triggered much discussion: it has been defined and redefined, and at times attacked and deconstructed, by writers including Wolterstorff, Goodman, Levinson, Davies, Nattiez, Goehr, Abbate and Parmer, to name but a few. More often than not, it is treated either as an abstract sound-structure or, in contrast, as a culturally constructed concept, even a chimera. But what is a musical work to the performer, actively engaged in a “relationship” with the work he or she is interpreting? This question, not asked often enough in scholarship, can be used to yield fascinating insights into the ontological status of the work. My thesis therefore explores the relationship between the musical work and the performance, with a specific focus on classical pianists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I make use of two methodological starting-points for considering the nature of the work. Firstly, I survey what pianists have said and written in interviews and biographies regarding their role as interpreters of works. Secondly, I analyse pianists’ use of tempo fluctuation at structurally significant moments in a selection of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach and Frederic Chopin. -

Degaetano CONCERTO NO. 1 CHOPIN

RobertDeGAETANO CONCERTO DeGaetano NO. 1 CHOPIN CONCERTO NO. 1 Because of my lack of experience as a composer I didn’t realize The Saga of Piano Concerto No. 1 how much was involved in such an undertaking or what the costs would be. BY ROBERT DeGAETANO I quickly started writing away. The music came very quickly. My first piano concerto began many years ago. I heard a theme I felt like I was a conduit and it poured right through me. that I knew was mine. At the time I had just begun composing seriously and I was instantly aware that this theme was for a A performance date and rehearsal was arranged with Stephen major work, either a concerto or symphony. It was grand in Osmond, conductor of the Jackson Symphony and we were off design and had a monumental quality. This was not a melody and running. I mean literally running! I believe I had less than three to be used in a shorter work. I remember jotting it down and months from the date of the commission to the actual premier. storing it with my manuscript paper. Fortunately I had a little cabin in the northern Catskills of NY where I was able to concentrate freely. In 1986 I gave a concert in “ The music came New York and premiered After completing the piano part and a general sketch of the my first piano Sonata very quickly. I felt orchestration, I set forth on the orchestration. I also had to deal dedicated to my maternal with getting the work copied legibly from the original score. -

Digital Concert Hall Where We Play Just for You

www.digital-concert-hall.com DIGITAL CONCERT HALL WHERE WE PLAY JUST FOR YOU PROGRAMME 2016/2017 Streaming Partner TRUE-TO-LIFE SOUND THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL AND INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN In the Digital Concert Hall, fast online access is com- Internet Initiative Japan Inc. is one of the world’s lea- bined with uncompromisingly high quality. Together ding service providers of high-resolution data stream- with its new streaming partner, Internet Initiative Japan ing. With its expertise and its excellent network Inc., these standards will also be maintained in the infrastructure, the company is an ideal partner to pro- future. The first joint project is a high-resolution audio vide online audiences with the best possible access platform which will allow music from the Berliner Phil- to the music of the Berliner Philharmoniker. harmoniker Recordings label to be played in studio quality in the Digital Concert Hall: as vivid and authen- www.digital-concert-hall.com tic as in real life. www.iij.ad.jp/en PROGRAMME 2016/2017 1 WELCOME TO THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL In the Digital Concert Hall, you always have Another highlight is a guest appearance the best seat in the house: seven days a by Kirill Petrenko, chief conductor designate week, twenty-four hours a day. Our archive of the Berliner Philharmoniker, with Mozart’s holds over 1,000 works from all musical eras “Haffner” Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s for you to watch – from five decades of con- “Pathétique”. Opera fans are also catered for certs, from the Karajan era to today. when Simon Rattle presents concert perfor- mances of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre and The live broadcasts of the 2016/2017 Puccini’s Tosca. -

Vesko Eschkenazy

VESKO ESCHKENAZY Violin virtuoso, Vesko Eschkenazy is 1st Concertmaster of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra; a position he has held since January 1, 2000. “Vesko Eschkenazy is a brilliant violinist” – remarks the “De Telegraaf” in November 2000, one of the largest dailies in the Kingdom of Netherlands, after his interpretation of the Violin Concerto #1 by Szymanovski with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. Eschkenazy has been its concertmaster since the beginning of the 1999/2000 season. Born in Bulgaria in 1970 into a family of musicians, still a child, Vesko appeared as an orchestra leader. At 11 years old he became concertmaster of the youth Philharmonic Orchestra of Prof. Vladi Simeonov. He is a graduate of the L. Pipkov National Music School in Sofia and of the P. Vladiguerov State Music Academy where he studied violin with Angelina Atanazzova and Prof. Petar Hristoskov. In 1990, Vesko Eschkenazy left Bulgaria for London and completed a two year Masters Degree for solo performers with Prof. Ifra Neaman at the Guildhall School of Music, and received a Solo Recital Diploma – 1992. He is a laureate of the International Violin Competitions “Wieniawski” , Beijing and Carl Flesch in London. He performs extensively in Europe, USA, South America, India, China and takes part in the festivals Midem in Cannes, Montpellier and Atlantic – France, the Music Festivals in Nantes and Rheims, the New Year Music Festival in Sofia, Varna Summer and Apolonia. Vesko Eschkenazy has performed as soloist with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, English Chamber Orchestra, Monte Carlo Philharmonic, Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra, Mexico City Symphony, the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra, Prague Symphony Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, Bach Chamber Orchestra – Berlin to name a few. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

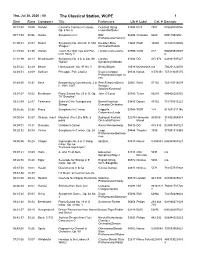

Thu, Jul 30, 2020 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 15:05 Handel Concerto Grosso in G minor, Guildhall String 01855 RCA 7907 078635790726 Op. 6 No. 6 Ensemble/Salter 00:17:3540:56 Dukas Symphony in C BBC 06394 Chandos 9225 09511592252 Philharmonic/Tortelier 01:00:01 28:03 Mozart Symphony No. 38 in D, K. 504 Dresden State 13266 Profil 14002 881488140026 “Prague” Orchestra/Haitink 01:29:0401:35 Walton Touch Her Soft Lips and Part London Concertante 07556 CMG 017 506005539007 from Henry V 0 01:31:39 28:13 Mendelssohn Symphony No. 4 in A, Op. 90 London 01044 DG 415 974 028941597427 "Italian" Symphony/Abbado 02:01:2202:29 Beach Honeysuckle, Op. 97 No. 5 Becky Billock 10038 MusesNine n/a 700261322070 02:04:5143:09 Sullivan Pineapple Poll, a ballet Royal Liverpool 08534 Naxos 8.570351 747313035175 Philharmonic/Lloyd-Jo nes 02:49:00 10:37 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in Petri/Friedrich/Berlin 05362 BMG 57130 743215713029 F, BWV 1047 Baroque Soloists/Kussmaul 03:01:0710:02 Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 25 in G, Op. John O'Conor 05592 Telarc 80293 089408029325 79 "Sonatina" 03:12:0922:47 Telemann Suite in D for Trumpet and Burns/American 03453 Dorian 80132 751758013223 Strings Concerto Orchestra 03:35:5622:38 Kraus Symphony in C minor Cappella 09048 WDR 174 811691011745 Coloniensis/Linde 04:00:0402:57 Strauss, Josef Moulinet (The Little Mill), a Budapest Festival 02279 Harmonia 903016 314902504814 polka Orchestra/Fischer Mundi 1 04:04:0115:31 Debussy Children's Corner Alexis Weissenberg 00436 DG 415 510 028941551023 04:20:3238:54 Vierne Symphony in A minor, Op. -

Ivajla Kirova – Biography

Piano Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Contents: Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Biography Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Curriculum Vitae Reviews Mailing Address: Press 1000 South Denver Avenue Interviews Suite 2104 Repertoire Tulsa, OK 74119 YouTube Video Links Website: Photo Gallery http://www.pricerubin.com Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Ivajla Kirova – Biography Ivajla Kirova is an initiator for establishment of the Association for promotion of Bulgarian Music in Germany and Artistic Director of the “Bulgarian music evenings in Munich” festival. “The young Bulgarian pianist is an example of how the Bulgarian art can be developed and supported even beyond the country’s frontiers”… announces the Deutsche Welle Radio. Ms. Kirova started playing a piano at the age of 7 and at 16 she was the youngest student at the Sofia Music Academy in Bulgaria. Her career started early when she won prizes for talented pianists (for example the prize awarded by the Polish Culture Institute in Sofia, Artist Award by Bel Canto Festival in Kuala Lumpur etc.). She has graduated the Sofia Music Academy with excellent grades diploma and has master diplomas for piano and chamber music issued by the Munich University of Music and Theater. Since 1999 she lives in Germany after she has been invited to become an associate professor at the Munich University of Music and Theater at the age of 24 years. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 97, 1977-1978

97th SEASON . TRUST BANKING. A symphony in financial planning. Conducted by Boston Safe Deposit and Trust Company Decisions which affect personal financial goals are often best made in concert with a professional advisor However, some situations require consultation with a number of professionals skilled in different areas of financial management. Real estate advisors. Tax consultants. Estate planners. Investment managers. To assist people with these needs, our venerable Boston banking institution has developed a new banking concept which integrates all of these professional services into a single program. The program is called trust banking. Orchestrated by Roger Dane, Vice President, 722-7022, for a modest fee. DIRECTORS Hans H. Estin George W. Phillips C. Vincent Vappi Vernon R. Alden Vice Chairman, North Executive Vice President, Vappi & Chairman, Executive American Management President Company, Inc. Committee Corporation George Putnam JepthaH. Wade Nathan H. Garrick, Jr. Putnam Partner, Choate, Hall Dwight L. Allison, Jr. Chairman, Vice Chairman of the Chairman of the Board Management & Stewart Board David C. Crockett Company, Inc. William W.Wolbach Donald Hurley Deputy to the Chairman J. John E. Rogerson Vice Chairman Partner, Goodwin, of the Board of Trustees Partner, Hutchins & of the Board Procter & Hoar and to the General Wheeler Honorary Director Director, Massachusetts Robert Mainer Henry E. Russell Sidney R. Rabb General Hospital Senior Vice President, President Chairman, The Stop & The Boston Company, Inc. F. Stanton Deland, jr. Mrs. George L. Sargent Shop Companies, Partner, Sherburne, Inc. Director of Various Powers & Needham William F. Morton Corporations Director of Various Charles W. Schmidt Corporations President, S.D. Warren LovettC. -

Saturday Playlist

August 31, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “To achieve great things, two things are needed: a plan, and not quite enough time.” — Leonard Bernstein Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Rimsky- Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Sadko, Op. 5 (Symphonic Poem) Rotterdam Philharmonic/Zinman Philips 411 446 028941144621 Korsakov 00:13 Buy Now! Pfitzner Symphony for Large Orchestra, Op. 46 Bamberg Symphony/Albert CPO 080 761203908028 00:31 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64 Chen/Swedish Radio Symphony/Harding Sony 88697984102 886979841024 Swedish Rhapsody No. 1, Op. 19 01:01 Buy Now! Alfven Baltimore Symphony/Comissiona MMG 10015 04716300152 "Midsummer Vigil" 01:14 Buy Now! Beethoven Violin Sonata No. 1 in D, Op. 12 No. 1 Perlman/Ashkenazy London 417 573 028941757326 01:38 Buy Now! Bach Sonata No. 3 in C, BWV 1005 Manuel Barrueco EMI 56416 724355641625 Royal Opera House, Covent Garden 02:00 Buy Now! Ponchielli Dance of the Hours ~ La gioconda Decca 289 473 171 028947317128 /Solti Sonata in A for Violin and Basso 02:10 Buy Now! Zipoli Francia/Videla Jade 91007 641359100722 Continuo 02:19 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36 Philharmonia/Muti Brilliant Classics 99792/4 5028421979243 03:00 Buy Now! Wagner Prelude to Act 1 ~ Parsifal Royal Concertgebouw/Haitink Philips 420 886 028942088627 03:13 Buy Now! Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue Bernstein/Columbia Symphony Sony Classical 46715 07464467152 Symphony No. 3 in G, "The Great 03:30 Buy Now! Clementi Philharmonia/d'Avalos ASV 247 743625024722 National" 04:01 Buy Now! Brahms Viola Sonata in E flat, Op.120 No.2 Kashkashian/Levin ECM 1630 78118216302 04:23 Buy Now! Schumann Manfred Overture, Op. -

NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 10,000Th CONCERT

' ■ w NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 10,000th CONCERT NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC 10,000th CONCERT Sunday, March 7,1982, 5:00 pm Mahler Symphony No. 2 (Resurrection) Zubin Mehta, Music Director and Conductor Kathleen Battle, soprano Maureen Forrester, contralto Westminster Choir, Joseph Flummerfelt, director CONTENTS The First 9,999 Concerts.................................... 2 Bernstein, Boulez, Mehta By Herbert Kupferberg.................................................. 5 New York Philharmonic: The Tradition of Greatness Continues By Howard Shanet........................................................ 8 Gustav Mahler and the New York Philharmonic............................... 14 Contemporary Music and the New York Philharmonic............................... 15 AVERY FISHER HALL, LINCOLN CENTER THE FIRST 9,999 CONCERTS The population of New York City in NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC: 1982 is 20 times what it was in 1842; the each of them. To survey them is to Philharmonic’s listeners today are define the current richness of the 10,000 times as many as they were in that organization: THE TRADITION OF GREATNESS CONTINUES The Subscription Concerts au dience, though not the largest of the their diversity they reflect the varied en Battle, David Britton, Montserrat aballé, Jennifer Jones, Christa Lud- in Avery Fisher Hall. As for television, it ig, Jessye Norman, and Frederica von is estimated that six million people Stade. (Another whole category across the country saw and heard the like - the < iductors. those chosen Philharmonic in a single televised per formance when the celebrated come dian Danny Kaye conducted the Or chestra recently in a Pension Fund benefit concert; and in a season's quota who is Music Director, of "Live from Lincoln Center" and other telecasts by the Philharmonic 20 are presented elsewhere in this publi million watchers may enjoy the Or chestra's performances in their homes. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 92, 1972-1973

1 H Shfcfti* Bin wVE S££3Wm si Eh! 0*r HKs& Bp9 *rjtti Kan ^- 1 Btjfe^r ? "T* 1- - 1 ^OtnL *3r hew fe^Sl madUs g 1 JEST-* 1 The Boston Symphony Orchestra presents the one hundred and fifty-eighth PENSION FUND CONCERT ALEXIS WEISSENBERG mm of 19 members the %.:* BOSTON SYMPHONY CHAMBER PLAYERS lllW'ln ii BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ngui^ • SEIJI OZAWA Music Adviser ITTirpilnr .r^n BSem IK and Bflh 4H SEIJI OZAWA Sunday evening February 18 1973 SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS «£££ y$& ^H » K ws> • *.*u -To'v-' H << «. Kfl Baal 21V, ffflfffll %c* Sunday evening February 18 1973 at 6.30 The first concert in the Cabot-Cahners Room ALEXIS WEISSENBERG piano MEMBERS OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY CHAMBER PLAYERS RALPH GOMBERG oboe HAROLD WRIGHT clarinet SHERMAN WALT bassoon CHARLES KAVALOSKI horn BEETHOVEN Quintet in E flat for piano and winds op. 16 Grave - allegro ma non troppo Andante cantabile Rondo: allegro ma non troppo Alexis Weissenberg plays the Steinway piano THE BOSTON SYMPHONY CHAMBER PLAYERS RECORD EXCLUSIVELY FOR DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON BALDWIN PIANO DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON & RCA RECORDS THE BOSTON SYMPHONY PENSION INSTITUTION The Boston Symphony Pension Institution, established in 1903, is the oldest among American symphony orchestras. During the past few years the Pension Institution has paid annually over 400,000 dollars to nearly one hundred pensioners and their widows. Pension Institution income is derived from Pension Fund concerts, from open rehearsals in Sym- phony Hall and at Tanglewood and from radio broadcasts, for which the members of the Orchestra donate their services. Contributions are also made each year by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

The Pianistic Legacy of Olga Samaroff: Her Contributions to the Musical World

The Pianistic Legacy of Olga Samaroff: Her Contributions to the Musical World The Pianistic Legacy of Olga Samaroff: Her Contributions to the Musical World Reiko ISHII Key Words: Olga Samaroff, piano pedagogy, pianist, teaching philosophy 1. Introduction 1.1 Purpose of the study This study examines the life and accomplishments of Olga Samaroff, one of the most famous and influential American musicians during the first half of the twentieth century, and discusses her contributions to music education and the musical world. Samaroff was an international concert pianist and a wife of the conductor Leopold Stokowski as well as a successful piano teacher and writer. This research begins with her biography, describes her pedagogical method and teaching philosophy, and then, discusses how her unique teaching method and high standards of musicianship influenced and contributed to culture and society in the U.S. 1.2 Significance of the study To date, research concerning Olga Samaroff is limited even though she made distinguished contributions to the classical music scene. Samaroff is a legendary but almost forgotten pianist of the early 1900’s who was overshadowed by Leopold Stokowski, her second husband as well as renowned conductor. Especially outside of the U.S., she is relatively unknown to most people and there is no publication available on Samaroff in Japan. In general, traditional piano teaching method is that student should follow what teacher says and imitate his or her teachers’ performance. Samaroff’s teaching method and philosophy were completely opposite from the traditional one. There were two purposes of her piano teaching, musical independence and human development of piano students.