Bach's Goldberg Variations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Firlngllne Copyright University

rights other a All infringement. makes resale. for user a copyright not If for are liable material. be Copies may 94305-6010 user copyrighted prohibited. CA of is that use, New FIRlnGLlne This Transcripts 29205 HOST GUESTS FIRING Stanford, SUBJECT fair distribution of is reproductions York 8031799-3449 : a and further transcript LINE excess University, : other videocassettes : City in or and is , March "IS WILLIAM Stanford produced material. ROSALYN of reprints purposes a re GOOD this FIRING available for photocopies of 31, of Archives, and 1999, additional MUSIC through copies) re-use and Copyright F. LINE TURECK making directed BUCKLEY, any and Producers the Library program purposes; GOING telecast 1999 before handwritten by Inc and governs o FIRING WARREN rporated Institution owner SCHUYLER #2833/1200, UNDER?" JR. later educational Code) (including fo LINE and Hoover r on Television, U.S. copyright public University. 17, STEIBEL. the Jr. Director, taped CHAPIN reproduction 2700 (Title from television or Cypress Stanford contact at non-commercial, States HBO Street, permission photocopy Leland stations United private, a Columbia, Studios the for the obtain information, of is uses of to . SC later laws further in or material Trustees advised For of for, this are of copyright ©Board reserved. Users Use The request © Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. MR. BUCKLEY: Every few years Firing Line touches down on the question, Is classical music dying? We are lucky enough this time around to have got in to discuss the question two persons who have spoken to us before on the subject. One is perhaps the most distinguished pianist alive, the second, the senior man of music in New York City. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

June WTTW & WFMT Member Magazine

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide As we approach the end of another busy fiscal year, I would like to take this opportunity to express my The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT heartfelt thanks to all of you, our loyal members of WTTW and WFMT, for making possible all of the quality Renée Crown Public Media Center content we produce and present, across all of our media platforms. If you happen to get an email, letter, 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue or phone call with our fiscal year end appeal, I’ll hope you’ll consider supporting this special initiative at Chicago, Illinois 60625 a very important time. Your continuing support is much appreciated. Main Switchboard This month on WTTW11 and wttw.com, you will find much that will inspire, (773) 583-5000 entertain, and educate. In case you missed our live stream on May 20, you Member and Viewer Services can watch as ten of the area’s most outstanding high school educators (and (773) 509-1111 x 6 one school principal) receive this year’s Golden Apple Awards for Excellence WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 in Teaching. Enjoy a wide variety of great music content, including a Great Chicago Production Center Performances tribute to folk legend Joan Baez for her 75th birthday; a fond (773) 583-5000 look back at The Kingston Trio with the current members of the group; a 1990 concert from the four icons who make up the country supergroup The Websites wttw.com Highwaymen; a rousing and nostalgic show by local Chicago bands of the wfmt.com 1960s and ’70s, Cornerstones of Rock, taped at WTTW’s Grainger Studio; and a unique and fun performance by The Piano Guys at Red Rocks: A Soundstage President & CEO Special Event. -

The Pianist's Freedom and the Work's Constrictions

The Pianist’s Freedom and the Work’s Constrictions What Tempo Fluctuation in Bach and Chopin Indicate Alisa Yuko Bernhard A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Alisa Yuko Bernhard 10 November 2016 i Abstract The concept of the musical work has triggered much discussion: it has been defined and redefined, and at times attacked and deconstructed, by writers including Wolterstorff, Goodman, Levinson, Davies, Nattiez, Goehr, Abbate and Parmer, to name but a few. More often than not, it is treated either as an abstract sound-structure or, in contrast, as a culturally constructed concept, even a chimera. But what is a musical work to the performer, actively engaged in a “relationship” with the work he or she is interpreting? This question, not asked often enough in scholarship, can be used to yield fascinating insights into the ontological status of the work. My thesis therefore explores the relationship between the musical work and the performance, with a specific focus on classical pianists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I make use of two methodological starting-points for considering the nature of the work. Firstly, I survey what pianists have said and written in interviews and biographies regarding their role as interpreters of works. Secondly, I analyse pianists’ use of tempo fluctuation at structurally significant moments in a selection of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach and Frederic Chopin. -

Grigori Sokolov

GRIGORI SOKOLOV at the Théâtre des Champs- Elysées - Paris, 2002 A dim light picks out the outlines of the hall. Suddenly a massive shadow appears and moves swiftly over to the keyboard, the only brightly lit surface to stand out from the large coffin- like box in the center of the stage. There follows the vaguest of unsmiling acknowledgments in the general direction of the audience, and then the music begins. Throughout the next two hours this music will keep its listeners enthralled with its extraordinary intensity as the audience senses the formidable physical, pianistic, musical and emotional presence of this most secretive of present- day pianists, Grigory Sokolov. S ecretive, he certainly is. A man of vast culture, cheerful and even mischievous offstage, he seems to be cocooned within his own irrefutable logic. Only his musical thoughts are susceptible of being imparted to the public, thoughts embodied beneath his fingers with the utmost interiority and within the ephemeral and exclusive framework of the concert hall. All other considerations, including those of career and self- promotion, are rejected as external to the music. They are, strictly speaking, irrelevant. The phenomenon of the artist retiring behind his art is both intriguing and salutary. It no doubt accounts partly to the fact that Sokolov is still relatively unknown to the public at large. Yet there are many people who are convinced that, following the deaths of musicians like Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Glenn Gould and Sviatoslav Richter, he is now the greatest -

Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson

Some Recent Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson The original European Universal Eloquence label replaced budget releases on DG (Privilege or Resonance), Decca (Weekend Classics) and Philips (Classical Favourites). Like them it originally sold for around £5 and offered some splendid bargains such as Telemann’s ‘Water Music’ and excerpts from Tafelmusik (Musica Antiqua Köln/Reinhard Goebel 4696642) and Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (Janet Baker, James King, Concertgebouw/Bernard Haitink 4681822). Later most of the original batch were deleted – luckily the Mahler remains available – and production switched to Universal Australia but the price remained around the same. More recently changes in the value of the £ mean that single CDs now sell for around £7.75 but the high quality of much of the repertoire means that they remain well worth keeping an eye on. Many, but not all, of the albums are available to stream or download and I have reviewed some in that form and others on CD. Be aware, however, that the downloads often cost more than the CDs and invariably come without notes – which is a shame because the Eloquence booklets are better than those of many budget labels. THE TUDORS Lo, Country Sports Anonymous Almain Thomas TOMKINS Adieu, Ye City-Prisoning Towers Thomas WEELKES Lo, Country Sports that Seldom Fades Nicholas BRETON Shepherd and Shepherdess Michael EAST Sweet Muses, Nymphs and Shepherds Sporting Bar YOUNG The Shepherd, Arsilius’s, Reply John FARMER O Stay, Sweet Love Giles FARNABY Pearce did love fair Petronel Michael -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

Guildhall School Gold Medal 2020 Programme

Saturday 26 September 7pm Gold Medal 2020 Finalists Soohong Park Ben Tarlton Ke Ma Guildhall Symphony Orchestra Richard Farnes conductor Guildhall School of Music & Drama Founded in 1880 by the City of London Corporation Chairman of the Board of Governors Vivienne Littlechild Principal Lynne Williams am Vice Principal & Director of Music Jonathan Vaughan Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk Guildhall School is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation Gold Medal 2020 Saturday 26 September, 7pm The Gold Medal, Guildhall School’s most prestigious award for musicians, was founded and endowed in 1915 by Sir H. Dixon Kimber Bt MA Guildhall Symphony Orchestra Finalists Richard Farnes conductor Soohong Park piano During adjudication, Junior Guildhall Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in violinist Leia Zhu performs Ravel’s C minor Op 18 Tzigane with pianist Kaoru Wada. Leia’s Ben Tarlton cello performance was recorded in January 2020. Elgar Cello Concerto in E minor Op 85 The presentation of the Gold Medal will Ke Ma piano take place after Leia’s performance. Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No 1 in B-flat minor Op 23 The Jury Jonathan Vaughan Vice-Principal & Director of Music Richard Farnes Conductor Emma Bloxham Editor, BBC Radio 3 Nicholas Mathias Director, IMG Artists Performed live on Friday 25 September and recorded and produced live by Guildhall School’s Recording and Audio Visual department. Gold Medal winners -

Zu Opus Klassik

Nominierte in der Kategorie Instrumentalist/in des Jahres Hinrich Alpers Piotr Anderszewski Nicholas Angelich Iveta Apkalna Martha Argerich Martha Argerich Bach: Well-tempered Beethoven / Liszt Clavier Prokofiev Widor & Vierne Beethoven / Grieg Beethoven Avi Avital Sergio Azzolini Sergei Babayan Daniel Barenboim Thomas Bartlett Lisa Batiashvili Art of the Mandolin Kozeluch: Concertos Rachmaninoff Complete Piano Sonatas Shelter City Lights and Symphony / Diabelli Variations Nominierte in der Kategorie Instrumentalist/in des Jahres Katharina Bäuml Nicola Benedetti Kristian Bezuidenhout Eva Bindere Claudio Bohórquez Gábor Boldoczki Earth Music Elgar: Violin Concerto Beethoven: 9. Sinfonie / Tālivaldis Ķeniņš Piazzolla Versailles Chorfantasie Luiza Borac Rudolf Buchbinder Khatia Buniatishvili Gautier Capuçon Renaud Capuçon Bertrand Chamayou Constantin Silvestri Beethoven: Piano Concerto 1 Labyrinth Emotions Elgar: Violin concerto Good Night! Nominierte in der Kategorie Instrumentalist/in des Jahres Seong-Jin Cho Zlata Chochieva Florian Christl Daniel Ciobanu Carlos Cipa Xavier de Maistre The Wanderer (re)creations Episodes Daniel Ciobanu Correlations (on 11 pianos) Serenata Latina Nikola Djoric Magne H. Draagen Friedemann Eichhorn Isang Enders Christian Euler Reinhold Friedrich Echoes of Leipzig in Bach & Piazzolla Say: Complete Violin Vox Humana Viola Solo Blumine Nidaros Cathedral Works Nominierte in der Kategorie Instrumentalist/in des Jahres Reinhold Friedrich Sebastian Fritsch Martin Fröst Thibaut Garcia Brandon Patrick George Alban -

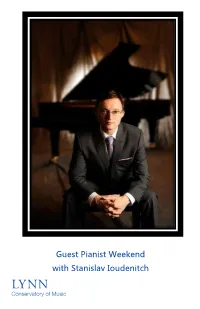

2016-2017 Master Class-Stanislav Ioudenitch

Guest Pianist Weekend with Stanislav Ioudenitch Pianist Stanislav Ioudenitch In Recital Saturday, Dec. 3 7:30 p.m. Count and Countess de Hoernle International Center Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall PROGRAM Spanish Rhapsody Franz Liszt Partita No. 2 in C minor JS Bach Sinfonia Allemande Courante Sarabande Rondeaux Capriccio Moment Musicaux Franz Schubert No. 3 Allegro moderato in F minor No. 4 Moderato in C-sharp minor Sonata No. 2 (1913 edition) Sergei Rachmaninoff Allegro agitato Non allegro Allegro molto Artist Biography STANISLAV IOUDENITCH has garnered notable successes in music competitions including the Gold Medal at the XI Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2001. The Van Cliburn Competition launched a career that has taken Ioudenitch around the world for appearances with major venues, including Carnegie Hall, the Kennedy Center, Fort the Moscow Conservatoire, Mariinsky Concert Hall, the Great Hall of the St Petersburg Philharmonic, the Conservatorio Giuseppe Verdi in Milan, the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, the Oriental Art Center in Shanghai and appeared at major festivals including the International Piano Festival in the United States and the Ruhr Music Festival in Germany among others. Ioudenitch has collaborated with a wide range of international conductors including James Conlon, Valery Gergiev, Mikhail Pletnev, Asher Fisch, Vladimir Spivakov, Günther Herbig, Pavel Kogan, James DePreist, Michael Stern, Stefan Sanderling, Carl St. Clair and Justus Frantz, and with such orchestras as the National Symphony in Washington DC, the Munich Philharmonic, Mariinsky Orchestra, the Rochester Philharmonic, the National Philharmonic of Russia, the Fort Worth Symphony and the Kansas City Symphony among others. He has also performed with the Takács, Prazák and Borromeo String Quartets and is a founding member of the Park Piano Trio. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

20180118 Communiqué Groupe CANAL+ Lancement Deutsche Grammophon

LE PLUS BEAU CATALOGUE MONDIAL DE MUSIQUE CLASSIQUE ENFIN SUR VOTRE TV AVEC CANAL+ Paris, 18 janvier 2018 Le Groupe CANAL+ et Universal Music Group s’associent pour lancer une nouvelle chaîne basée sur le célèbre catalogue de Deutsche Grammophon. Cette chaîne digitale premium permettra notamment aux abonnés équipés du nouveau décodeur CANAL de profiter de l’incroyable richesse du catalogue du « label jaune », avec des enregistrements audios proposés en haute résolution et, pour la première fois, en DOLBY ATMOS. Cette chaîne interactive, disponible pour les abonnés en France au cours du deuxième trimestre 2018, leur permettra de découvrir le catalogue Deutsche Grammophon à travers différentes catégories - compositeurs, interprètes, genres musicaux, instruments - ainsi qu’à travers des playlists thématiques. Des contenus vidéo de musique classique viendront ensuite enrichir cette offre. A propos de Deutsche Grammophon : Deutsche Grammophon, l’un des plus prestigieux noms dans l’univers mondial de la musique classique depuis sa création en 1898, a toujours défendu les plus hauts standards de l’art et de la qualité sonore. Maison des plus grands artistes de l’histoire de la musique, le célèbre « label jaune » est une référence pour tous les amoureux de la musique à travers le monde, amateurs des plus remarquables enregistrements et interprétations. Deutsche Grammophon compte aujourd’hui à son répertoire parmi les plus grands artistes de la musique classique : Anne-Sophie Mutter, Anna Netrebko, Martha Argerich, Daniel Barenboim, Hélène Grimaud, Evgeny Kissin, Lang Lang, Murray Perahia, Maurizio Pollini, Grigory Sokolov, Daniil Trifonov, Krystian Zimerman, Gustavo Dudamel, Andris Nelsons, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, El īna Garan ča, Bryn Terfel, Rolando Villazón et Max Richter.