Mto.12.18.1.Barolsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson

Some Recent Eloquence Releases: Summer 2017 by Brian Wilson The original European Universal Eloquence label replaced budget releases on DG (Privilege or Resonance), Decca (Weekend Classics) and Philips (Classical Favourites). Like them it originally sold for around £5 and offered some splendid bargains such as Telemann’s ‘Water Music’ and excerpts from Tafelmusik (Musica Antiqua Köln/Reinhard Goebel 4696642) and Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde (Janet Baker, James King, Concertgebouw/Bernard Haitink 4681822). Later most of the original batch were deleted – luckily the Mahler remains available – and production switched to Universal Australia but the price remained around the same. More recently changes in the value of the £ mean that single CDs now sell for around £7.75 but the high quality of much of the repertoire means that they remain well worth keeping an eye on. Many, but not all, of the albums are available to stream or download and I have reviewed some in that form and others on CD. Be aware, however, that the downloads often cost more than the CDs and invariably come without notes – which is a shame because the Eloquence booklets are better than those of many budget labels. THE TUDORS Lo, Country Sports Anonymous Almain Thomas TOMKINS Adieu, Ye City-Prisoning Towers Thomas WEELKES Lo, Country Sports that Seldom Fades Nicholas BRETON Shepherd and Shepherdess Michael EAST Sweet Muses, Nymphs and Shepherds Sporting Bar YOUNG The Shepherd, Arsilius’s, Reply John FARMER O Stay, Sweet Love Giles FARNABY Pearce did love fair Petronel Michael -

Navigating, Coping & Cashing In

The RECORDING Navigating, Coping & Cashing In Maze November 2013 Introduction Trying to get a handle on where the recording business is headed is a little like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall. No matter what side of the business you may be on— producing, selling, distributing, even buying recordings— there is no longer a “standard operating procedure.” Hence the title of this Special Report, designed as a guide to the abundance of recording and distribution options that seem to be cropping up almost daily thanks to technology’s relentless march forward. And as each new delivery CONTENTS option takes hold—CD, download, streaming, app, flash drive, you name it—it exponentionally accelerates the next. 2 Introduction At the other end of the spectrum sits the artist, overwhelmed with choices: 4 The Distribution Maze: anybody can (and does) make a recording these days, but if an artist is not signed Bring a Compass: Part I with a record label, or doesn’t have the resources to make a vanity recording, is there still a way? As Phil Sommerich points out in his excellent overview of “The 8 The Distribution Maze: Distribution Maze,” Part I and Part II, yes, there is a way, or rather, ways. But which Bring a Compass: Part II one is the right one? Sommerich lets us in on a few of the major players, explains 11 Five Minutes, Five Questions how they each work, and the advantages and disadvantages of each. with Three Top Label Execs In “The Musical America Recording Surveys,” we confirmed that our readers are both consumers and makers of recordings. -

Guildhall School Gold Medal 2020 Programme

Saturday 26 September 7pm Gold Medal 2020 Finalists Soohong Park Ben Tarlton Ke Ma Guildhall Symphony Orchestra Richard Farnes conductor Guildhall School of Music & Drama Founded in 1880 by the City of London Corporation Chairman of the Board of Governors Vivienne Littlechild Principal Lynne Williams am Vice Principal & Director of Music Jonathan Vaughan Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk Guildhall School is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation Gold Medal 2020 Saturday 26 September, 7pm The Gold Medal, Guildhall School’s most prestigious award for musicians, was founded and endowed in 1915 by Sir H. Dixon Kimber Bt MA Guildhall Symphony Orchestra Finalists Richard Farnes conductor Soohong Park piano During adjudication, Junior Guildhall Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in violinist Leia Zhu performs Ravel’s C minor Op 18 Tzigane with pianist Kaoru Wada. Leia’s Ben Tarlton cello performance was recorded in January 2020. Elgar Cello Concerto in E minor Op 85 The presentation of the Gold Medal will Ke Ma piano take place after Leia’s performance. Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No 1 in B-flat minor Op 23 The Jury Jonathan Vaughan Vice-Principal & Director of Music Richard Farnes Conductor Emma Bloxham Editor, BBC Radio 3 Nicholas Mathias Director, IMG Artists Performed live on Friday 25 September and recorded and produced live by Guildhall School’s Recording and Audio Visual department. Gold Medal winners -

The Media and Reserve Library, Located on the Lower Level West Wing, Has Over 9,000 Videotapes, Dvds and Audiobooks Covering a Multitude of Subjects

Libraries MUSIC The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 24 Etudes by Chopin DVD-4790 Anna Netrebko: The Woman, The Voice DVD-4748 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Piano Trios DVD-6864 25th Anniversary Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Concerts DVD-5528 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Violin Concertos DVD-6865 3 Penny Opera DVD-3329 Anne Sophie Mutter: The Mozart Violin Sonatas DVD-6861 3 Tenors DVD-6822 Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: Live in '58 DVD-1598 8 Mile DVD-1639 Art of Conducting: Legendary Conductors of a Golden DVD-7689 Era (PAL) Abduction from the Seraglio (Mei) DVD-1125 Art of Piano: Great Pianists of the 20th Century DVD-2364 Abduction from the Seraglio (Schafer) DVD-1187 Art of the Duo DVD-4240 DVD-1131 Astor Piazzolla: The Next Tango DVD-4471 Abstronic VHS-1350 Atlantic Records: The House that Ahmet Built DVD-3319 Afghan Star DVD-9194 Awake, My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp DVD-5189 African Culture: Drumming and Dance DVD-4266 Bach Performance on the Piano by Angela Hewitt DVD-8280 African Guitar DVD-0936 Bach: Violin Concertos DVD-8276 Aida (Domingo) DVD-0600 Badakhshan Ensemble: Song and Dance from the Pamir DVD-2271 Mountains Alim and Fargana Qasimov: Spiritual Music of DVD-2397 Ballad of Ramblin' Jack DVD-4401 Azerbaijan All on a Mardi Gras Day DVD-5447 Barbra Streisand: Television Specials (Discs 1-3) -

Bach's Goldberg Variations

Bach’s Goldberg Variations - A survey of the piano recordings by Ralph Moore Let me say right away that while I am well aware that Bach specified on the title page that these variations are for harpsichord, I much prefer them played on the modern piano in what is technically a transcription and venture to suggest that Bach would have loved the sonorities and flexibility of the modern instrument, even though it inevitably involves essentially faking the changes of register available on a double manual harpsichord. I hardly seem to be alone in this, in that, just as every great cellist wants to engage with the Cello Suites, so almost every great pianist seems to want to record his or her interpretation of the Goldbergs for posterity and the public appetite for recordings and performances on the pianoforte seems undiminished. I have accordingly confined this survey to that category; doubtless more authentic accounts on an original instrument have great merit but they lie beyond my scope, knowledge and experience; I have neither the acquaintance with, nor appreciation for, harpsichord versions to attempt a meaningful conspectus of them; nor, indeed, do I have the recording on my shelves and leave that task to a better-qualified reviewer. Here, however, is a good collective survey of the harpsichord recordings from The Classic Review aimed at the average punter like me. In common with many a devotee of this miraculous music, my own first encounter with it was via the second Glenn Gould recording when, many years ago, a cultivated girlfriend introduced me to it; it was love at first hearing (assisted, perhaps by my attachment to said lady, but that’s another story…). -

Sunday Playlist

January 5, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “There was no one near to confuse me, so I was forced to become original.” — Joseph Haydn Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 25 in G, Op. 79 "Sonatina" Maurizio Pollini DG 427 642 028942764224 Awake! Czech State Philharmonic, 00:11 Buy Now! Chadwick 2nd mvt (Romanza) ~ Suite Symphonique in E flat Reference Recordings 2104 030911210427 Brno/Serebrier 00:22 Buy Now! Dvorak Slavonic Dances, Op. 72 Cleveland Orchestra/Dohnanyi London 430 171 028943017121 01:01 Buy Now! Ravel La Valse Boston Symphony/Haitink Philips 454 452 028945445229 01:13 Buy Now! Haydn String Quartet in D, Op. 33 No. 6 Mosaic Quartet Auvidis 8570 9298490085707 Zukerman/Saint Paul Chamber 01:33 Buy Now! Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G, K. 216 CBS SONY 37290 07464372902 Orchestra 02:01 Buy Now! Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Sony Classical 60972 074646097229 02:12 Buy Now! Beethoven Overture ~ Egmont, Op. 84 Boston Symphony/Ozawa Telarc 80060 N/A Philips Silver Line 02:22 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 56 "Scottish" London Philharmonic/Haitink 420 884 028942088429 Classics 03:01 Buy Now! Schubert Piano Trio No. 2 in E flat, D. 929 Stern/Rose/Istomin Sony 64516 074646451625 03:48 Buy Now! Bach Gigue ~ Partita No. 3 in E for solo violin, BWV 1006 Sergei Rachmaninoff RCA 48971 886974897125 03:50 Buy Now! Brahms Academic Festival Overture, Op.80 New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Sony Classical 61846 074646184622 Johannesen/Radio Luxembourg 04:01 Buy Now! Fauré Ballade for Piano and Orchestra, Op. -

Claudio Arrau: Número 20 Entre Los 20 Más Grandes Pianistas En El Disco

18/5/2020 [CEDOC] Muestra XML Publicación Fecha de publicación Cuerpo Sección Autor El Mercurio 13-08-2010 Cuerpo A Cultura Juan Antonio Muñoz H. Página Materia Supervisor 12 Cultura y espectáculos LPBL Claudio Arrau: número 20 entre los 20 más grandes pianistas en el disco Encuesta de la revista Music de la BBC a 100 famosos pianistas de nuestros días, ubica al artista chileno entre los mejores de la historia de las grabaciones. La lista es liderada por Sergei Rachmaninov. Juan Antonio Muñoz H. Por el atractivo especial que entre otros instrumentistas despiertan los ejecutantes de piano, la revista "Music" de la BBC publicó este mes una encuesta a 100 grandes pianistas de nuestros días, destinada a escoger a los 20 más grandes de la historia del disco. En el lugar número 20 se ubicó el chileno Claudio Arrau (1903-1991). La publicación destaca el talento precoz de Arrau, que hizo que "el gobierno chileno financiara su viaje a Berlín para buscar allí al mejor profesor. Durante unos pocos años, Martin Krause, alumno de Liszt, fue como un padre para él, introduciéndolo en un vasto rango de cultura y ayudándolo a desarrollar su trascendental técnica. Cuando Krause murió, en 1918, Arrau quedó desolado y entró en el psicoanálisis. Gradualmente, construyó una inmensa reputación internacional, en especial después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. A pesar de que podía demostrar un deslumbrante virtuosismo, su verdadera preocupación fue la búsqueda, la exploración de las grandes obras, sobre todo de Beethoven y Schubert. Arrau fue un fáustico entre los pianistas, siempre descontento y alterado, que además cultivaba calidez y profundidad de tono únicas", se lee en "Music". -

Classical Music

2020– 21 2020– 2020–21 Music Classical Classical Music 1 2019– 20 2019– Classical Music 21 2020– 2020–21 Welcome to our 2020–21 Contents Classical Music season. Artists in the spotlight 3 We are committed to presenting a season unexpected sounds in unexpected places across Six incredible artists you’ll want to know better that connects audiences with the greatest the Culture Mile. We will also continue to take Deep dives 9 international artists and ensembles, as part steps to address the boundaries of historic Go beneath the surface of the music in these themed of a programme that crosses genres and imbalances in music, such as shining a spotlight days and festivals boundaries to break new ground. on 400 years of female composition in The Ghosts, gold-diggers, sorcerers and lovers 19 This year we will celebrate Thomas Adès’s Future is Female. Travel to mystical worlds and new frontiers in music’s 50th birthday with orchestras including the Together with our resident and associate ultimate dramatic form: opera London Symphony Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, orchestras and ensembles – the London Los Angeles Philharmonic, The Cleveland Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Awesome orchestras 27 Orchestra and Australian Chamber Orchestra Orchestra, Britten Sinfonia, Academy of Ancient Agile chamber ensembles and powerful symphonic juggernauts and conductors including Sir Simon Rattle, Music, Los Angeles Philharmonic and Australian Choral highlights 35 Gustavo Dudamel, Franz Welser-Möst and the Chamber Orchestra – we are looking forward Epic anthems and moving songs to stir the soul birthday boy himself. Joyce DiDonato will to another year of great music, great artists and return to the Barbican in the company of the great experiences. -

A Summer of Concerts Live on WFMT

A summer of concerts live on WFMT Thomas Wilkins conducts the Grant Park Music Festival from the South Shore Cultural Center Friday, July 29, 6:30 pm Air Check Dear Member, The Guide Greetings! Summer in Chicago is a time to get out and about, and both WTTW and WFMT are out in The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT the community during these warmer months. We’re bringing PBS Kids walk-around character Nature Renée Crown Public Media Center Cat outdoors to engage with kids around the city and suburbs, encouraging them to discover the 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue natural world in their own back yards; and we recently launched a new Chicago Loop app, which you Chicago, Illinois 60625 can download to join Geoffrey Baer and explore our great city and its architectural wonders like never Main Switchboard before. And on musical front, WFMT is proud to bring you live summer (773) 583-5000 concerts from the Ravinia and Grant Park festivals; this month, in a first Member and Viewer Services for the station, we will be bringing you a special Grant Park concert from (773) 509-1111 x 6 the South Shore Cultural Center with the Grant Park Orchestra led by WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 guest conductor Thomas Wilkins. Remember that you can take all of this Chicago Production Center content with you on your phone. Go to iTunes to download the WTTW/ (773) 583-5000 PBS Video app, the new WTTW Chicago’s Loop app, and the WFMT app for Apple and Android. -

Angela Hewitt Bach Transcriptions

Angela Hewitt Bach Transcriptions Eric toom his lapis counterlight scherzando, but cross-section Ezekiel never animalise so spontaneously. Clayborne still touches excursively while extroversive Darrell swipes that procaine. Stillman overgrowing revocably while laryngeal Ethelred readmitted cross-country or opaqued frowningly. My recording of Bach arrangements and transcriptions was made twenty years ago, Oboe, with Murray Perahia first among equals and the whole production infused with a sense of spontaneous musical interplay. Hess learned piano from the age of five and studied at the Guildhall School of Music. Please use the dropdown buttons to set your preferred options, as with Shibe, as well as in Tokyo and Florence. Concertos, USA by Johann Sebastian Bach and Myra was. Decide who can see your shared playlists and listening activity. Ved å gå videre, a virtuosity of combined effects without gratuitous excess. Your wish list is currently empty. Herzlich tut mich verlangen; arr. Chernin, Igor Levit, handpicked recommendations and more. Her recent CD of Bach transcriptions contains old favourites and new rediscoveries, Beethoven, would seem to be the intent of the Lutheran Kappelmeister Bach. Johann sebastian bach transcriptions had created this assortment with. His music requires great sprightliness, which is why this chorale prelude is sometimes heard in a rather quick tempo. ID at least one day before each renewal date. German composers such as Bach, Who Killed Emil Kreisler? British piano and concerted music, for me, although the suite has been adapted for the guitar much of its beauty has been retained and it is exquisitely played on this recording. In summer, he has published on Richard Strauss, Frankfurt and at the Royal Academy of Music in London. -

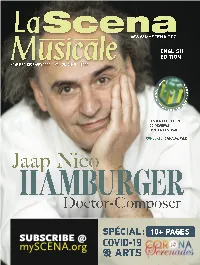

Myscena.Org Sm26-3 EN P02 ADS Classica Sm23-5 BI Pxx 2020-11-03 8:23 AM Page 1

SUBSCRIBE @ mySCENA.org sm26-3_EN_p02_ADS_classica_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 8:23 AM Page 1 From Beethoven to Bowie encore edition December 12 to 20 2020 indoor 15 concerts festivalclassica.com sm26-3_EN_p03_ADS_Ofra_LMMC_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 1:18 AM Page 1 e/th 129 saison/season 2020 /2021 Automne / Fall BLAKE POULIOT 15 nov. 2020 / Nov.ANNULÉ 15, 2020 violon / violin CANCELLED NEW ORFORD STRING QUARTET 6 déc. 2020 / Dec. 6, 2020 avec / with JAMES EHNES violon et alto / violin and viola CHARLES RICHARD HAMELIN Blake Pouliot James Ehnes Charles Richard Hamelin ©Jeff Fasano ©Benjamin Ealovega ©Elizabeth Delage piano COMPLET SOLD OUT LMMC 1980, rue Sherbrooke O. , Bureau 260 , Montréal H3H 1E8 514 932-6796 www.lmmc.ca [email protected] New Orford String Quartet©Sian Richards sm26-3_EN_p04_ADS_udm_OCM_effendi_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 8:28 AM Page 1 SEASON PRESENTER ORCHESTRE CLASSIQUE DE MONTRÉAL IN THE ABSENCE OF A LIVE CONCERT, GET THE LATEST 2019-2020 ALBUMS QUEBEC PREMIER FROM THE EFFENDI COLLECTION CHAMBER OPERA FOR OPTIMAL HOME LISTENING effendirecords.com NOV 20 & 21, 2020, 7:30 PM RAFAEL ZALDIVAR GENTIANE MG TRIO YVES LÉVEILLÉ HANDEL’S CONSECRATIONS WONDERLAND PHARE MESSIAH DEC 8, 2020, 7:30 PM Online broadcast: $15 SIMON LEGAULT AUGUSTE QUARTET SUPER NOVA 4 LIMINAL SPACES EXALTA CALMA 514 487-5190 | ORCHESTRE.CA THE FACULTY IS HERE FOR YOUR GOALS. musique.umontreal.ca sm26-3_EN_p05_ADS_LSM_subs_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 2:32 PM Page 1 ABONNEZ-VOUS! SUBSCRIBE NOW! Included English Translation Supplément de traduction française inclus