The Catholic Church's War with Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

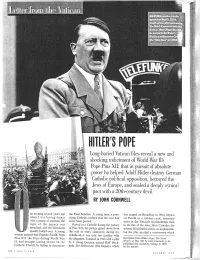

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Katholisches Wort in Die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014

Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem katholischen Glauben treu!“ 68 Gerhard Stumpf: Reformer und Wegbereiter in der Kirche: Klemens Maria Hofbauer 76 Franz Salzmacher: Europa am Scheideweg 82 Katholisches Wort in die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014 DER FELS 3/2014 65 Formen von Sexualität gleich- Liebe Leser, wertig sind. Eine Vorgeschichte hat weiterhin die Insolvenz des kircheneigenen Unternehmens der Karneval ist in der katho- „Weltbild“. Das wirtschaftliche lischen Welt zuhause, wo sich Desaster ist darauf zurückzufüh- der Rhythmus des Lebens auch ren, dass die Geschäftsführung im Kirchenjahr widerspiegelt. zu spät auf das digitale Geschäft Die Kirche kennt eben die Natur gesetzt hat. Hinzu kommt die INHALT des Menschen und weiß, dass er Sortimentsausrichtung, die mit auch Freude am Leben braucht. Esoterik, Pornographie und sa- tanistischer Literatur, trotz vie- Papst Franziskus: Lebensfreude ist nicht gera- Das Licht Christi in tiefster Finsternis ....67 de ein Zeichen, das unsere Zeit ler Hinweise über Jahrzehnte, charakterisiert. Die zunehmen- keineswegs den Anforderungen Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: : den psychischen Erkrankungen eines kircheneigenen Medien- Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem sprechen jedenfalls nicht dafür. unternehmens entsprach. Eine katholischen Glauben treu!“ .................68 „Schwermut ist die Signatur der Vorgeschichte hat schließlich die Gegenwart geworden“, lautet geistige Ausrichtung des ZDK Raymund Fobes: der Titel eines Artikels, der die- und der sie tragenden Großver- Seid das Salz der Erde ........................72 ser Frage nachgeht (Tagespost, bände wie BDKJ, katholische 1.2.14). Frauenverbände etc. Prälat Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Lothar Roos: Die Menschen erleben heute, Die selbsternannten „Refor- „Ein Licht für das Leben mer“ der deutschen Ortskirche in der Gesellschaft“ (Lumen fidei) .........74 dass sie mit verdrängten Prob- lemen immer mehr in Tuchfüh- ereifern sich immer wieder ge- Gerhard Stumpf: lung kommen. -

American Catholicism and the Political Origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1991 American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M. Moriarty University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Moriarty, Thomas M., "American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/" (1991). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1812. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1812 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORI ARTY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 1991 Department of History AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORIARTY Approved as to style and content by Loren Baritz, Chair Milton Cantor, Member Bruce Laurie, Member Robert Jones, Department Head Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. "SATAN AND LUCIFER 2. "HE HASN'T TALKED ABOUT ANYTHING BUT RELIGIOUS FREEDOM" 25 3. "MARX AMONG THE AZTECS" 37 4. A COMMUNIST IN WASHINGTON'S CHAIR 48 5. "...THE LOSS OF EVERY CATHOLIC VOTE..." 72 6. PAPA ANGEL I CUS 88 7. "NOW COMES THIS RUSSIAN DIVERSION" 102 8. "THE DEVIL IS A COMMUNIST" 112 9. -

The Diplomatic Mission of Archbishop Flavio Chigi, Apostolic Nuncio to Paris, 1870-71

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1974 The Diplomatic Mission of Archbishop Flavio Chigi, Apostolic Nuncio to Paris, 1870-71 Christopher Gerard Kinsella Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Recommended Citation Kinsella, Christopher Gerard, "The Diplomatic Mission of Archbishop Flavio Chigi, Apostolic Nuncio to Paris, 1870-71" (1974). Dissertations. 1378. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1378 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1974 Christopher Gerard Kinsella THE DIPLOMATIC MISSION OF ARCHBISHOP FLAVIO CHIGI APOSTOLIC NUNCIO TO PARIS, 1870-71 by Christopher G. Kinsella t I' A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty:of the Graduate School of Loyola Unive rsi.ty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy February, 197 4 \ ' LIFE Christopher Gerard Kinsella was born on April 11, 1944 in Anacortes, Washington. He was raised in St. Louis, where he received his primary and secondary education, graduating from St. Louis University High School in June of 1962, He received an Honors Bachelor of Arts cum laude degree from St. Louis University,.., majoring in history, in June of 1966 • Mr. Kinsella began graduate studies at Loyola University of Chicago in September of 1966. He received a Master of Arts (Research) in History in February, 1968 and immediately began studies for the doctorate. -

Dignitatis Humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Barrett Hamilton Turner Washington, D.C 2015 Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty Barrett Hamilton Turner, Ph.D. Director: Joseph E. Capizzi, Ph.D. Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Liberty, Dignitatis humanae (DH), poses the problem of development in Catholic moral and social doctrine. This problem is threefold, consisting in properly understanding the meaning of pre-conciliar magisterial teaching on religious liberty, the meaning of DH itself, and the Declaration’s implications for how social doctrine develops. A survey of recent scholarship reveals that scholars attend to the first two elements in contradictory ways, and that their accounts of doctrinal development are vague. The dissertation then proceeds to the threefold problematic. Chapter two outlines the general parameters of doctrinal development. The third chapter gives an interpretation of the pre- conciliar teaching from Pius IX to John XXIII. To better determine the meaning of DH, the fourth chapter examines the Declaration’s drafts and the official explanatory speeches (relationes) contained in Vatican II’s Acta synodalia. The fifth chapter discusses how experience may contribute to doctrinal development and proposes an explanation for how the doctrine on religious liberty changed, drawing upon the work of Jacques Maritain and Basile Valuet. -

The Pius XII Controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, Et Al

Consensus Volume 26 Article 7 Issue 2 Apocalyptic 11-1-2000 The iuP s XII controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, et al Oscar Cole-Arnal Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus Recommended Citation Cole-Arnal, Oscar (2000) "The iusP XII controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, et al," Consensus: Vol. 26 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol26/iss2/7 This Studies and Observations is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Consensus by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Pius XII Controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, et. al. Oscar L. Cole-Arnal Professor of Historical Theology Waterloo Lutheran Seminary Waterloo, Ontario ew would dispute that Eugenio Pacelli, better known as Pope Pius XII, remains one of the most controversial figures of this Fcentury. Although his reign lasted twenty years (1939-1958), the debate swirls around his career as a papal diplomat in Germany from I 1917 to 1939 (the year he became pope) and the period of his papacy I i that overlapped with World War II. Questions surrounding his relation- ship with Hitler’s Third Reich (1933-1945) and his policy decisions with respect to the Holocaust extend far beyond the realm of calm historical research to the point of acrimonious polemics. In fact, virtually all the I studies which have emerged about Pius XII after the controversial play I The Deputy (1963) by Rolf Hochhuth range between histories with po- lemical elements to outright advocacy works for or against. -

Pius Ix and the Change in Papal Authority in the Nineteenth Century

ABSTRACT ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Andrew Paul Dinovo This thesis examines papal authority in the nineteenth century in three sections. The first examines papal issues within the world at large, specifically those that focus on the role of the Church within the political state. The second section concentrates on the authority of Pius IX on the Italian peninsula in the mid-nineteenth century. The third and final section of the thesis focuses on the inevitable loss of the Papal States within the context of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870. Select papal encyclicals from 1859 to 1871 and the official documents of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870 are examined in light of their relevance to the change in the nature of papal authority. Supplementing these changes is a variety of seminal secondary sources from noted papal scholars. Ultimately, this thesis reveals that this change in papal authority became a point of contention within the Church in the twentieth century. ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Andrew Paul Dinovo Miami University Oxford, OH 2004 Advisor____________________________________________ Dr. Sheldon Anderson Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. Wietse de Boer Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. George Vascik Contents Section I: Introduction…………………………………………………………………….1 Section II: Primary Sources……………………………………………………………….5 Section III: Historiography……...………………………………………………………...8 Section IV: Issues of Church and State: Boniface VIII and Unam Sanctam...…………..13 Section V: The Pope in Italy: Political Papal Encyclicals….……………………………20 Section IV: The Loss of the Papal States: The Vatican Council………………...………41 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..55 ii I. -

Gottes Mächtige Dienerin Schwester Pascalina Und Papst Pius XII

Martha Schad Gottes mächtige Dienerin Schwester Pascalina und Papst Pius XII. Mit 25 Fotos Herbig Für Schwester Dr. Uta Fromherz, Kongregation der Schwestern vom Heiligen Kreuz, Menzingen in der Schweiz Inhalt Teil I Inhaltsverzeichnis/Leseprobe aus dem Verlagsprogramm der 1894–1929 Buchverlage LangenMüller Herbig nymphenburger terra magica In der Nuntiatur in München und Berlin Bitte beachten Sie folgende Informationen: Von Ebersberg nach Altötting 8 Der Inhalt dieser Leseprobe ist urheberrechtlich geschützt, Im Dienst für Nuntius Pacelli in München und Berlin 20 alle Rechte liegen bei der F. A. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, München. Die Leseprobe ist nur für den privaten Gebrauch bestimmt und darf nur auf den Internet-Seiten www.herbig.net, Teil II www.herbig-verlag.de, www.langen-mueller-verlag.de, 1930–1939 www.nymphenburger-verlag.de, www.signumverlag.de und www.amalthea-verlag.de Im Vatikan mit dem direkt zum Download angeboten werden. Kardinalstaatssekretär Pacelli Die Übernahme der Leseprobe ist nur mit schriftlicher Genehmigung des Verlags Besuchen Sie uns im Internet unter: Der vatikanische Haushalt 50 gestattet. Die Veränderungwww d.heer digitalenrbig-verlag Lese.deprobe ist nicht zulässig. Reisen mit dem Kardinalstaatssekretär 67 »Mit brennender Sorge«, 1937 85 © 2007 by F.A. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, München Alle Rechte vorbehalten Umschlaggestaltung: Wolfgang Heinzel Teil III Umschlagbild: Hans Lehnert, München 1939–1958 und dpa/picture-alliance, Frankfurt Lektorat: Dagmar von Keller Im Vatikan mit Papst Pius XII. Herstellung und Satz: VerlagsService Dr. Helmut Neuberger & Karl Schaumann GmbH, Heimstetten Judenverfolgung, Hunger und Not 94 Gesetzt aus der 11,5/14,5 Punkt Minion Das päpstliche Hilfswerk – Michael Kardinal Drucken und Binden: GGP Media GmbH, Pößneck Printed in Germany von Faulhaber 110 ISBN 978-3-7766-2531-8 Mächtige Hüterin 146 Teil IV 1959–1983 Oberin am päpstlichen nordamerikanischen Priesterkolleg in Rom Der vatikanische Haushalt Leben ohne Papst Pius XII. -

Quanta Cura & the Syllabus of Errors

The Great Papal Encyclicals Quanta Cura & The Syllabus of Errors Condemning Current Errors Pius IX ENCYCLICAL LETTER Quanta Cura & The Syllabus of Errors OF THE SUPREME PONTIFF PIUS IX Condemning Current Errors December 8,1864 ANGELUS PRESS 2918 TRACY AVENUE KANSAS CITY MISSOURI 64109 2 Encyclical Letter of Pope Pius IX Quanta Cura1 Condemning Current Errors December, 8, 1864 To Our Venerable Brethren, all Patriarchs, Primates, Archbishops and Bishops having Favor and Communion of the Holy See. Venerable Brethren, Health and Apostolic Benediction. 1. It it well known unto all men, and especially to You, Venerable Brothers, with what great care and pasto- ral vigilance Our Predecessors, the Roman Pontiffs, have discharged the Office entrusted by Christ Our Lord to them, in the Person of the Most Blessed Peter, Prince of the Apostles, have unremittingly discharged the duty of feeding the lambs and the sheep, and have diligently nour- ished the Lord’s entire flock with the words of faith, im- bued it with salutary doctrine, and guarded it from poi- soned pastures. And those Our Predecessors, who were the assertors and Champions of the august Catholic Re- ligion, of truth and justice, being as they were chiefly solicitous for the salvation of souls, held nothing to be of so great importance as the duty of exposing and condemn- ing, in their most wise Letters and Constitutions, all her- esies and errors which are hostile to moral honesty and to the eternal salvation of mankind, and which have fre- quently stirred up terrible commotions and have dam- aged both the Christian and civil commonwealths in a disastrous manner. -

Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw

DIALOG, KOMUNIKACJA. UJĘCIE INTERDYSCYPLINARNE Prof. UKSW, PhD Paweł Mazanka, CSsR, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1389-7588 Department of Metaphysics Institute of Philosophy Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński – a man of dialogue Kardynał Stefan Wyszyński – człowiek dialogu https://doi.org/10.34766/fetr.v46i2.863 Abstract: Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński was not only an “unbreakable Primate”, but above all, a man of dialogue. He was able to meet every person and to talk to them. In his conversations, he listened patiently, he did not impose his opinion and he was mostly trying to seek for common levels of agreement. According to him, the greatest wisdom is to be able to unite, not to divide. The article indicates some sources and forms of this dialogue. It was a supernatural source and a natural one. The first one is a permanent dialogue of the Primate with God, as well as with the Blessed Mother and with saints. Cardinal Wyszyński was a man of deep prayer, and he undeniably took from this source strength for everyday meetings, conversations, and making decisions. The second crucial source was his philosophico-theological education. As a Christian personalist, the Primate took from the achievements of such thinkers as Aristotle, St. Thomas, St. Augustin, as well as J. Maritain, G. Marcel, J. Woroniecki, and W. Korniłowicz. The article discusses some aspects of dialogue with people, taking into account, above all, two social groups: youth, and , and representatives of the communist state power. Presenting Cardinal Wyszyński as a man of dialogue seems to be very useful and topical nowadays because of different controversies and disputes occurring in our state, in our Church and in relationships between the older and the younger generation. -

Holy Land and Holy See

1 HOLY LAND AND HOLY SEE PAPAL POLICY ON PALESTINE DURING THE PONTIFICATES OF POPES PIUS X, BENEDICT XV AND PIUS XI FROM 1903 TO 1939 PhD Thesis Gareth Simon Graham Grainger University of Divinity Student ID: 200712888 26 July 2017 2 CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction – Question, Hypothesis and Methodology Chapter 2: A Saint for Jerusalem – Pope Pius X and Palestine Chapter 3: The Balfour Bombshell – Pope Benedict XV and Palestine Chapter 4: Uneasy Mandate – Pope Pius XI and Palestine Chapter 5: Aftermath and Conclusions Appendix 1.The Roads to the Holy Sepulchre – Papal Policy on Palestine from the Crusades to the Twentieth Century Appendix 2.The Origins and Evolution of Zionism and the Zionist Project Appendix 3.The Policies of the Principal Towards Palestine from 1903 to 1939 Appendix 4. Glossary Appendix 5. Dramatis Personae Bibliography 3 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION – QUESTION, HYPOTHESIS AND METHODOLOGY 1.1. THE INTRIGUING QUESTION Invitation to Dr Theodor Herzl to attend Audience with Pope Pius X On 25 January 1904, the Feast of the Conversion of St Paul, the recently-elected Pope Pius X granted an Audience in the Vatican Palace to Dr Theodor Herzl, leader of the Zionist movement, and heard his plea for papal approval for the Zionist project for a Jewish national home in Palestine. Dr Herzl outlined to the Supreme Pontiff of the Catholic Church the full details of the Zionist project, providing assurances that the various Holy Places in Palestine would be “ex-territorialised” to ensure their security and protection, and sought the Pope’s endorsement and support, preferably through the issuing of a pro-Zionist encyclical. -

Palestine and Transjordan in Transition (1945–47)

Chapter 1 Palestine and Transjordan in Transition (1945–47) 1 Framing the Background 1.1 “Non possumus”? The Alternate Relations between the Holy See and the Zionist Movement (1897–1939) At the turn of the twentieth century, the Holy See’s concern about the situation of Catholics in the eastern Mediterranean was not limited to the rivalry among European powers to achieve greater prominence and recognition in Jerusalem. By the end of the nineteenth century, a new actor had appeared on the scene: the Jewish nationalist movement, Zionism, whose significance seemed to be on the increase all over Europe after it had defined its program and as the num- ber of Jews emigrating to Palestine after the first aliyah (1882–1903) became more consistent.1 The Zionist leaders soon made an attempt at mediation and rapproche- ment with the Holy See.2 Indeed, the Vatican’s backing would have been 1 From the vast bibliography on Zionism, see, in particular, Arturo Marzano, Storia dei sion- ismi: Lo Stato degli ebrei da Herzl a oggi (Rome: Carocci, 2017); Walid Khalidi, From Haven to Conquest: Readings in Zionism and the Palestine Problem until 1948, 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 2005); Alain Dieckhoff, The Invention of a Nation: Zionist Thought and the Making of Modern Israel, trans. Jonathan Derrick (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003); Georges Bensoussan, Une histoire intellectuelle et politique du sionisme, 1860–1840 (Paris: Fayard, 2002); Walter Laqueur, A History of Zionism (New York: Schocken, 1989); Arthur Hertzberg, ed., The Zionist Idea: A Historical Analysis and Reader (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1959).