The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 Ii Introduction Introduction Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Times (A.D

The Catholic Faith History of Catholicism A Brief History of Catholicism (Excerpts from Catholicism for Dummies) Ancient Times (A.D. 33-741) Non-Christian Rome (33-312) o The early Christians (mostly Jews who maintained their Jewish traditions) o Jerusalem’s religious establishment tolerated the early Christians as a fringe element of Judaism o Christianity splits into its own religion . Growing number of Gentile converts (outnumbered Jewish converts by the end of the first century) . Greek and Roman cultural influences were adapted into Christianity . Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in A.D. 70 (resulted in the final and formal expulsion of the Christians from Judaism) o The Roman persecutions . The first period (A.D. 68-117) – Emperor Nero blamed Christians for the burning of Rome . The second period (A.D. 117-192) – Emperors were less tyrannical and despotic but the persecutions were still promoted . The third period (A.D. 193-313) – Persecutions were the most virulent, violent, and atrocious during this period Christian Rome (313-475) o A.D. 286 Roman Empire split between East and West . Constantinople – formerly the city of Byzantium and now present- day Istanbul . Rome – declined in power and prestige during the barbarian invasions (A.D. 378-570) while the papacy emerged as the stable center of a chaotic world o Roman Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan in A.D. 313 which legalized Christianity – it was no longer a capital crime to be Christian o A.D. 380 Christianity became the official state religion – Paganism was outlawed o The Christian Patriarchs (Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, Rome, and Constantinople) . -

All'ombra Delle Querce Di Monte Sole

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI FERRARA FACOLTA’ DI LETTERE E FILOSOFIA Corso di laurea in Filosofia ALL’OMBRA DELLE QUERCE DI MONTE SOLE riflessioni sulla kenosi del monaco Giuseppe Dossetti al cospetto della storia e del mistero di Israele laureando Giambattista Zampieri relatore correlatore prof. Piero Stefani prof. Mario Miegge Anno Accademico 2006-2007 Indice INTRODUZIONE AL COSPETTO DELLA STORIA p. 1 Premessa 1 Vita 5 Piano di lavoro 25 CAPITOLO I DA MONTE SOLE A SIGHET (l’idolatria e la città) 29 Le querce testimoni del martirio 30 La Shoah come unicum 34 Un delitto castale 41 Gemeinschaft e città 49 CAPITOLO II IL MISTERO DI ISRAELE (il silenzio e l’elezione) 67 Dopo Auschwitz, dopo Cristo 68 Chi è come Te fra i muti? 73 Scrutando il mistero della Chiesa 78 L’impossibile antisemitismo 94 L’elezione del popolo mediatore 102 CAPITOLO III LA KENOSI DEL MEDIATORE (la croce e la Chiesa) 128 Questo è Dio 129 Fino alla morte e alla morte di croce 140 La kenosi della Chiesa 148 Già e non ancora: un confronto con Sergio Quinzio 157 CONCLUSIONE L’OMBRA DELLE QUERCE 175 Memoria sapienziale 176 L’azione preveniente dello Spirito 182 BIBLIOGRAFIA 187 Scritti e discorsi di Giuseppe Dossetti (ordine cronologico) 187 Nota bibliografica (ordine alfabetico per autore) 199 INTRODUZIONE AL COSPETTO DELLA STORIA Premessa Questo lavoro si propone di enucleare alcuni aspetti del pensiero sviluppato da Giuseppe Dossetti soprattutto nella seconda parte della sua esistenza, quando assecondò l’improcrastinabile chiamata a realizzare nella vita monastica quanto sentiva impellente già dagli anni giovanili. Nel 1939 scriveva: “In che cosa la mia vita si caratterizza per quella di un’anima consacrata al Signore, più precisamente consacrata a Cristo Re, nel mondo? Per il fatto che scrivo così dei libri? No, certo. -

Antoine De Chandieu (1534-1591): One of the Fathers Of

CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): ONE OF THE FATHERS OF REFORMED SCHOLASTICISM? A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN MAY 2013 CALVIN THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 3233 Burton SE • Grand Rapids, Michigan • 49546-4301 800388-6034 fax: 616 957-8621 [email protected] www. calvinseminary. edu. This dissertation entitled ANTOINE DE CHANDIEU (1534-1591): L'UN DES PERES DE LA SCHOLASTIQUE REFORMEE? written by THEODORE GERARD VAN RAALTE and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy has been accepted by the faculty of Calvin Theological Seminary upon the recommendation of the undersigned readers: Richard A. Muller, Ph.D. I Date ~ 4 ,,?tJ/3 Dean of Academic Programs Copyright © 2013 by Theodore G. (Ted) Van Raalte All rights reserved For Christine CONTENTS Preface .................................................................................................................. viii Abstract ................................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1 Introduction: Historiography and Scholastic Method Introduction .............................................................................................................1 State of Research on Chandieu ...............................................................................6 Published Research on Chandieu’s Contemporary -

The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions

Scholars Crossing History of Global Missions Center for Global Ministries 2009 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions Don Fanning Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist Recommended Citation Fanning, Don, "The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions" (2009). History of Global Missions. 3. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/cgm_hist/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Global Ministries at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Global Missions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Middle Ages 500-1000 1 3 The Dark Age Church Period of Barbarian Invasions AD 500—1000 Introduction With the endorsement of the Emperor and obligatory church membership for all Roman citizens across the empire, Roman Christianity continued to change the nature of the Church, in stead of visa versa. The humble beginnings were soon forgotten in the luxurious halls and civil power of the highest courts and assemblies of the known world. Who needs spiritual power when you can have civil power? The transition from being the persecuted to the persecutor, from the powerless to the powerful with Imperial and divine authority brought with it the inevitable seeds of corruption. Some say that Christianity won the known world in the first five centuries, but a closer look may reveal that the world had won Christianity as well, and that, in much less time. The year 476 usually marks the end of the Christian Roman Empire in the West. -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

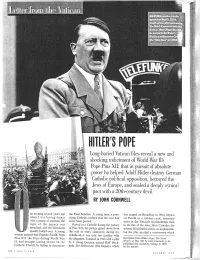

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Pius XII on Trial

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Pius XII on Trial Katherine M. Campbell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Katherine M., "Pius XII on Trial" (2014). Honors College. 159. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/159 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIUS XII ON TRIAL by Katherine M. Campbell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology and Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Henry Munson, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Grab, Professor of History Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor of Political Science, Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Copyright 2014 Katherine M. Campbell Abstract: Scholars have debated Pope Pius XII’s role in the Holocaust since the 1960s. Did he do everything he could and should have done to save Jews? His critics say no because of antisemitism rooted in the traditional Catholic views. His defenders say yes and deny that he was an antisemite. In my thesis, I shall assess the arguments on both sides in terms of the available evidence. I shall focus both on what Pius XII did do and what he did not do and on the degree to which he can be held responsible for the actions of low-level clergy. -

Hans Urs Von Balthasar - Ein Grosser Churer Diözesan SCHRIFTENREIHE DER THEOLOGISCHEN HOCHSCHULE CHUR

Peter HENR1c1 (Hrsg.) Hans Urs von Balthasar - ein grosser Churer Diözesan SCHRIFTENREIHE DER THEOLOGISCHEN HOCHSCHULE CHUR Im Auftragder Theologischen Hochschule Chur herausgegeben von Michael DURST und Michael FIEGER Band7 Peter HENRICI (Hrsg.) Hans Urs von Balthasar - ein grosser Churer Diözesan Mit Beiträgen von Urban FINK Alois M. HAAS Peter HENRICI KurtKocH ManfredLOCHBRUNNER sowie einer Botschaft von Papst BENEDIKT XVI. AcademicPress Fribourg BibliografischeInformation Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografischeDaten sind im Internetüber http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. Die Druckvorlagen der Textseiten wurden vom Herausgeber der Reihe als PDF-Datei zur Verfügunggestellt. © 2006 by Academic Press Fribourg / Paulusverlag Freiburg Schweiz Herstellung: Paulusdruckerei Freiburg Schweiz ISBN-13: 978-3-7278-1542-3 ISBN-10: 3-7278-1542-6 Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort . 7 Abkürzungsverzeichnis . 9 Bischof Kurt KOCH Von der Schönheit Gottes Zeugnis geben . 11 Alois M. HAAS Evangelisierung der Kultur . 19 Weihbischof Peter HENRICI Das Gleiche auf zwei Wegen: Karl Rahner und Hans Urs von Balthasar . 39 Manfred LOCHBRUNNER Hans Urs von Balthasar und seine Verbindung mit dem Bistum Chur . 55 Urban FINK „Ihr stets im Herrn ergebener Hans Balthasar“. Hans Urs von Balthasar und der Basler Bischof Franziskus von Streng . 93 Botschaft von Papst BENEDIKT XVI. an die Teilnehmer der Internationalen Tagung in Rom (Lateran-Universität) anlässlich des 100. Geburtstages des Schweizer Theologen Hans Urs von Balthasar . 131 Die Autoren . 135 5 Vorwort Hans Urs VON BALTHASAR ist wohl der weltweit bekannteste katholische Theologe der Deutschschweiz im 20. Jahrhundert. Dass der gebürtige Luzerner und „Basler Theologe“ Churer Diözesanpriester war, ist weit weniger bekannt. Sein 100. -

Learning from the Aftermath of the Holocaust G

Learning From The Aftermath Of The Holocaust G. Short, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research [IJHLTR], Volume 14, Number 2 – Spring/Summer 2017 Historical Association of Great Britain www.history.org.uk ISSN: 14472-9474 Abstract: In this article I seek to encourage those involved in Holocaust education in schools to engage not just with the Holocaust but also with its aftermath. I conceptualise the latter in terms of two questions; namely, what happened to those Jews who survived the Nazi onslaught and what became of the perpetrators? British researchers in the field of Holocaust education have largely ignored these questions, discovering only that many schools ignore them too. I argue that students are able to benefit in a number of ways from learning about the aftermath of the Holocaust, for the topic provides a sense of closure, allows for a more sophisticated understanding of the fate of European Jewry between 1933 and 1945 and also has the potential to promote responsible citizenship. Keywords: Citizenship, Curriculum, Holocaust Aftermath, Learning, Teaching INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HISTORICAL LEARNING, TEACHING AND RESEARCH Vol. 14.2 LEARNING FROM THE AFTERMATH OF THE HOLOCAUST G. Short, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, United Kingdom Abstract: In this article I seek to encourage those involved in Holocaust education in schools to engage not just with the Holocaust but also with its aftermath. I conceptualise the latter in terms of two questions; namely, what happened to those Jews who survived the Nazi onslaught and what became of the perpetrators? British researchers in the field of Holocaust education have largely ignored these questions, discovering only that many schools ignore them too. -

January 2011 Angelo Roncalli (John XXIII) Synopsis of Documents

January 2011 Angelo Roncalli (John XXIII) Synopsis of Documents Introduction: When reviewing Angelo Roncalli's activities in favor of the Jewish people across many years, one may distinguish three parts; the first, during the years 1940-1944, when he served as Apostolic Delegate of the Vatican in Istanbul, Turkey, with responsibility over the Balkan region. The second, as a Nuncio in France, in 1947, on the eve of the United Nations decision on the creation of a Jewish state. Finally, in 1963, as Pope John XXIII, when he brought about a radical positive change in the Church's position of the Jewish people. 1) As the Apostolic Delegate in Istanbul, during the Holocaust years, Roncalli aided in various ways Jewish refugees who were in transit in Turkey, including facilitating their continued migration to Palestine. His door was always open to the representatives of Jewish Palestine, and especially to Chaim Barlas, of the Jewish Agency, who asked for his intervention in the rescue of Jews. Among his actions, one may mention his intervention with the Slovakian government to allow the exodus of Jewish children; his appeal to King Boris II of Bulgaria not to allow his country's Jews to be turned over to the Germans; his consent to transmit via the diplomatic courier to his colleague in Budapest, the Nuncio Angelo Rotta, various documents of the Jewish Agency, in order to be further forwarded to Jewish operatives in Budapest; valuable documents to aid in the protection of Jews who were authorized by the British to enter Palestine. Finally, above all -- his constant pleadings with his elders in the Vatican to aid Jews in various countries, who were in danger of deportation by the Nazis. -

Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945

DECISIONS AMID CHAOS: JEWISH SURVIVAL IN BUDAPEST, MARCH 1944 – FEBRUARY 1945 Allison Somogyi A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Konrad Jarausch © 2014 Allison Somogyi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Allison Somogyi: Decisions amid Chaos: Jewish Survival in Budapest, March 1944 – February 1945 (Under the direction of Chad Bryant) “The Jews of Budapest are completely apathetic and do virtually nothing to save themselves,” Raoul Wallenberg stated bluntly in a dispatch written in July 1944. This simply was not the case. In fact, Jewish survival in World War II Budapest is a story of agency. A combination of knowledge, flexibility, and leverage, facilitated by the chaotic violence that characterized Budapest under Nazi occupation, helped to create an atmosphere in which survival tactics were common and widespread. This unique opportunity for agency helps to explain why approximately 58 percent of Budapest’s 200,000 Jews survived the war while the total survival rate for Hungarian Jews was only 26 percent. Although unique, the experience of Jews within Budapest’s city limits is not atypical and suggests that, when fortuitous circumstances provided opportunities for resistance, European Jews made informed decisions and employed everyday survival tactics that often made the difference between life and death. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank everybody who helped me and supported me while writing and researching this thesis. First and foremost I must acknowledge the immense support, guidance, advice, and feedback given to me by my advisor, Dr. -

Christopher White Table of Contents

Christopher White Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Peter the “rock”? ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Churches change over time ...................................................................................................................... 6 The Church and her earthly pilgrimage .................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1 The Apostle Peter (d. 64?) : First Bishop and Pope of Rome? .................................................. 11 Peter in Rome ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Yes and No .............................................................................................................................................. 13 The death of Peter .................................................................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2 Pope Sylvester (314-335): Constantine’s Pope ......................................................................... 16 Constantine and his imprint .................................................................................................................... 17 “Remembering” Sylvester ...................................................................................................................... -

Poles Under German Occupation the Situation and Attitudes of Poles During the German Occupation

Truth About Camps | W imię prawdy historycznej (en) https://en.truthaboutcamps.eu/thn/poles-under-german-occu/15596,Poles-under-German-Occupation.html 2021-09-25, 22:48 Poles under German Occupation The Situation and Attitudes of Poles during the German Occupation The Polish population found itself in a very difficult situation during the very first days of the war, both in the territories incorporated into the Third Reich and in The General Government. The policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Executions, resettlements, arrests, deportations to camps, and street round-ups were a constant element of the everyday life of Poles during the war. Initially the policy of the German occupier was primarily aimed at the liquidation of the Polish intellectual elite and leadership, and at the subsequent enslavement, maximal exploitation, and Germanization of Polish society. Terror was conducted on a mass and general scale. Food rationing was imposed in cities and towns, with food coupons covering about one-third of a person’s daily needs. Levies — obligatory, regular deliveries of selected produce — were introduced in the countryside. Farmers who failed to deliver their levy were subject to severe repressions, including the death penalty. Devaluation and difficulty with finding employment were the reason for most Poles’ poverty and for the everyday problems in obtaining basic products. The occupier also limited access to healthcare. The birthrate fell dramatically while the incidence of infectious diseases increased significantly.