UI Papers 19-Yulia Tsyryapkina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, Cryptinae)

© Biologiezentrum Linz, download www.zobodat.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 47/1 749-896 31.7.2015 Zur Kenntnis paläarktischer Cryptus-Arten (Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, Cryptinae) Martin SCHWARZ A b s t r a c t : Contribution to the knowledge of Palaearctic species of Cryptus (Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, Cryptinae). In this paper additions to the revision of the western Palaearctic species of the genus Cryptus (Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, Cryptinae) by ROSSEM (1969) are given. In addition the Cryptus species from Central Asia and from Mongolia are revised. New keys to the species occuring in the western Palaearctic region and in Central Asia as well as in Mongolia are provided. For most species new localities are listed. The following new species are described: Cryptus adversus nov.sp. (Kazakhstan), Cryptus borderai nov.sp. (Spain, Italy), Cryptus dentipropodealis nov.sp. (Portugal, Spain, Italy, Macedonia, Greece, Lebanon, Morocco), Cryptus duoalbimaculatus nov.sp. (Iran, Turkmenistan, Egypt), Cryptus infinitus nov.sp. (Mongolia), Cryptus informis nov.sp. (Greece, Iran), Cryptus laticlypeatus nov.sp. (Turkey, Tajikistan), Cryptus lobicaudatus nov.sp. (Jordan), Cryptus ludibundus nov.sp. (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan), Cryptus magniloquus nov.sp. (Russia, Kazakhstan, Mongolia), Cryptus mandschui nov.sp. (Mongolia), Cryptus meditatus nov.sp. (Tadshikistan), Cryptus memorandus nov.sp. (Mongolia), Cryptus meticulosus nov.sp. (Mongolia), Cryptus notaulicus nov.sp. (Turkey), Cryptus schenkioides nov.sp. (Turkey), Cryptus spissus nov.sp. (Turkey), Cryptus transversistriatus nov.sp. (Kyrgyzstan), Cryptus turbidus nov.sp. (Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia), Cryptus valesiacus nov.sp. (Switzerland), C. vicinalis nov.sp. (Mongolia) and Cryptus vitreifrontalis nov.sp. (Turkey, ?Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iran). For Itamoplex indicum JONATHAN 2000, which is preoccupied in Cryptus, a new name (Cryptus albidentatus nom.nov.) is presented. -

OPERATION SCHEME of the Executives of Sectors, Head Offices and Secretaries of Head Offices of Tashkent Region

OPERATION SCHEME of the Executives of Sectors, Head offices and secretaries of Head offices of Tashkent Region Sector 1 – Khokim’s Head office Sector 2 – Head office secretary of the Sector 3 –Head office secretary of the Sector 4 – Head office secretary of the secretary and location Prosecutor’s Office and location Department of Internal affairs (DIA) State Tax Inspectorate and location and location Khidoyatov Davron Abdulpattakhovich Samadov Salom Ismatovich Aripov Tokhir Tulkinovich Raimov Ravshan Isakjanovich KHOKIM OF THE REGION TASHKENT REGION PROSECUTOR MAIN DEPARTMENT OF INTERNAL STATE TAX INSPECTORATE OF HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: A. Eshbaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: М. Egamberdiev AFFAIRS OF TASHKENT REGION TASHKENT REGION Phone number: (98) 007-30-04 Phone number: (97) 733-57-37 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: F. HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: E. Djumabaev Location: 1, Almalik city, Tashkent region. Location: 1, Tashkent yuli, Nurafshan city. Khamitov Phone number: (93) 398-54-34 Phone of the Head office: (70) 201-07-34 +6448 Phone number: (99) 301-70-77 Location: 79 A, Babur str., Tashkent. Location: Mevazor, Kuyichirchik region. Phone of the Head office: (78) 150-49-56 Phone of the Head office: (95) 476-75 -77 Saliyev Muzaffar Kholdorbolevich Mirzayev Fakhriddin Yusupovich Amanbaev Navruz Zokirjonovich Narkhodjaev Sanjar Rashidovich KHOKIM OF NURAFSHAN CITY PROSECUTOR OF NURAFSHAN CITY DIA OF NURAFSHAN CITY NURAFSHAN CITY STATE TAX HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: О. Erbaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: М.Shukrullaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: F. INSPECTORATE Phone number: (99) 823-67-72 Phone: (97) 911-77-10 Imankulov HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: E. Igamnazarov Location: Tashkent yuli str., Nurafshan city. Location: 4A, Shon shukhrat str., Obod turmush Phone: (94) 631-49-37 Phone: (94) 930-03-73 CCU, Nurafshan city. -

UZBEKISTAN In-Depth Review

UZBEKISTAN In-Depth Review of the Investment Climate and Market Structure in the Energy Sector 2005 Energy Charter Secretariat ENERGY CHARTER SUMMARY AND MAIN FINDINGS OF THE SECRETARIAT Uzbekistan, a Central Asian country located at the ancient Silk Road, is rich in hydrocarbon resources, especially natural gas. Proved gas reserves amount to about 1.85 trillion cubic meters, exceeding the confirmed oil reserves of about 600 million barrels nearly 20-fold on energy equivalent basis. Most of the existing oil and gas fields are in the Bukhara-Kiva region which accounts for approximately 70 percent of Uzbekistan’s oil production. The second largest concentration of oil fields is in the Fergana region. Natural gas comes mainly from the Amudarya basin and the Murabek area in the southwest of Uzbekistan, making up almost 95 percent of total gas production. The endowment with oil and gas offers considerable potential for further economic development of Uzbekistan. Its recent economic performance has been promising, with a GDP growth of above 7 percent in 2004, and an outlook for continuous robust growth in 2005 and beyond. To what extent it can be realised depends crucially on how the government will pursue its policies concerning investment liberalisation and market restructuring, including privatisation, in the energy sector. While the Uzbek authorities recognize the critical role that foreign investment plays for the exploitation of the hydrocarbon resources and the overhaul of the existing energy infrastructure progress has been relatively slow concerning the establishment of a favourable investment climate for many years. However, the Government has recently adopted a far more positive stance that has already brought about tangible results. -

Housing for Integrated Rural Development Improvement Program

i Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Final Report June 2015 UZB: Housing for Integrated Rural Development Investment Program Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit under the Ministry of Economy for the Republic of Uzbekistan and The Asian Development Bank ii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence Review EIA Environmental Impact Assessment Housing for Integrated Rural Development HIRD Investment Program State committee for land resources, geodesy, SCLRGCSC cartography and state cadastre SCAC State committee of architecture and construction NPC Nature Protection Committee MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources QQL Qishloq Qurilish Loyiha QQI Qishloq Qurilish Invest This Due Diligence Report on Environmental and Social Safeguards is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 B. SUMMARY FINDINGS ............................................................................................... 4 C. SAFEGUARD STANDARDS ...................................................................................... -

COMMERCIAL PROPOSAL 1. Name of the Enterprise JSC Almalyk

COMMERCIAL PROPOSAL JSC Almalyk Mining and Metallurgical Combine Name of the enterprise 1. Brief information about the company The plant was founded in 1949 in the city of Almalyk, 2. (year of establishment, staff) Tashkent region, more than 33 thousand. Company logo 3. 110100, Uzbekistan, Tashkent region, Almalyk, st. Address 4. Amir Temur, 53 5. Full name of the head of the enterprise Farmanov Alexand Kasimovich 6. Phone +99871 141 9009 7. Fax +99871 141 9033 8. E-mail address [email protected] 9. Web-Site www.agmk.uz 10. Manufactured products Copper wire rod 11. Quality parameters of products Brand KM0, diameter 8 mm 12. Volume of production More than 10 thousand tons 13. O'z DST 2809: 2013, HS Code for Foreign Trade Certificate of quality 7408110000 14. Packaging Coils on pallets 15. Price (in USD / unit) LME for copper plus a premium of $ 80 / ton 16. Delivery condition FCA - Tashkent, JV of JSC "Uzkabel" 17. Product photos COMMERCIAL PROPOSAL JSC Almalyk Mining and Metallurgical Combine Name of the enterprise 1. Brief information about the company The plant was founded in 1949 in the city of Almalyk, 2. (year of establishment, staff) Tashkent region, more than 33 thousand. Company logo 3. 110100, Uzbekistan, Tashkent region, Almalyk, st. Amir Address 4. Temur, 53 5. Full name of the head of the Farmanov Alexand Kasimovich enterprise 6. Phone +99871 141 9009 7. Fax +99871 141 9033 8. E-mail address [email protected] 9. Web-Site www.agmk.uz 10. Manufactured products Copper wire 11. Quality parameters of products Mark MM, diameter 1-4 mm 12. -

Turakurgan Tpp Construction Board»

UE « TURAKURGAN TPP CONSTRUCTION BOARD» APPROVED BY Director of UE “Turakurgan TPP Construction Board” _______ Mullajanov T.H. «____»_____________2014 Environmental Impact Assessment of Connection of Existing 220 kV TL to Turaurgan TPP and Kyzyl-Ravat SS with Reconstruction of Kyzyl-Ravat SS Stage: DRAFT STATEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT (DSEI) DEVELOPED BY OJSC “Teploelectroproekt” Engineering director __________T.B. Baymatova «____»_____________2014 Tashkent-2014 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 2 1. DESCRIPTION OF THE EXISTING ENVIRONMENT IN THE AREA OF THE OBJECT ORIENTATION OF CONSTRUCTION .............................................................. 4 1.1.PHYSIOGRAPHIC AND CLIMATIC CONDITIONS ................................................... 4 1.2.EXISTING IMPACT SOURCES ..................................................................................... 9 1.3.SOIL CONDITIONS AND UNDERGROUND WATER .............................................. 14 1.4.AIR CONDITION ........................................................................................................... 15 1.5.SURFACE ARTIFICIAL AND NATURAL FLOW CONDITION. .......................... 16 1.6.VEGETATIVE GROUND COVER CONDITION ........................................................ 19 1.7. HEALTH STATUS OF THE POPULATION............................................................................... 21 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE DESIGN CONSIDERATION, DETECTION SOURCE -

Uzbekistan: Tashkent Province Sewerage Improvement Project

Initial Environmental Examination May 2021 Uzbekistan: Tashkent Province Sewerage Improvement Project Prepared by the Joint Stock Companies “Uzsuvtaminot” for the Asian Development Bank. ..Þ,zýUçâÛ,ÜINÞâ'' .,UzSUVTAMINoT" »KSIYADORLIK J°¼IY»ÂI JoINT ýâÞáÚ áÞÜà°ItÓr 1¾¾¾35, O'zbekiston Respublikasi l0OO35, Republic of Uzbekistan Toshkent shahri, Niyozbek yo'li ko'chasi 1-çã Tashkent ciý, Niyozbek 5ruli stÛÕÕt 1 apt. telefon: +998 55 5Þ3 l2 55 telephone: +998 55 503 12 55 uzst14,exat.uz, infcl(rtluzsuv. çz æzst{o exat. uz, iÛ[Þ(Ð æzsçç, æz _ 2 Ñ 1,1AÙ 202l Nq 4l2L 1 4 2 Ò ÂÞ: ¼r. Jung ½Þ ºim Project Officer SÕßiÞr UrÌÐß Development Specialist ÁÕßtrÐl and West Asia DÕàÐÓtmÕßt UrÌÐß Development and Water Division °siÐß Development ²Ðßk Subject: Project 52045-001 Tashkent ÀrÞçißáÕ Sewerage lmprovement Project - Revised lnitial Environmental Examination Dear ¼r. Kim, We hÕrÕÌà endorse the final revised and updated version of the lnitial µßvirÞßmÕßtÐl Examination (lEE) àrÕàÐrÕd fÞr the Tashkent ÀrÞçißáÕ Sewerage lmprovement ÀrÞjÕát. The lEE has ÌÕÕß discussed and reviewed Ìã the Projecls Coordination Unit ußdÕr JSc "UZSUVTAMlNoT". We ÕßSçrÕ, that the lEE will ÌÕ posted Þß the website of the JSC "UZSUVTAMlNoT" to ÌÕ available to the project affected àÕÞà|Õ, the printed áÞàã will also ÌÕ delivered to Ñ hokimiyats for disclosure to the local people. FuÓthÕr, hereby we submit the lEE to ADB for disclosure Þß the ÔD² website. Sincerely, Rusta janov Deputy irman of the Board CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 May 2021) Currency unit – Uzbekistan Sum (SUM) -

Developing Infrastructure in Central Asia: Impacts and Financing Mechanisms

DEVELOPING INFRASTRUCTURE IN CENTRAL ASIA Impacts and Financing Mechanisms Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, Bihong Huang, Dina Azhgaliyeva, and Qaisar Abbas ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE Developing Infrastructure in Central Asia: Impacts and Financing Mechanisms Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, Bihong Huang, Dina Azhgaliyeva, and Qaisar Abbas ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE © 2021 Asian Development Bank Institute All rights reserved. ISBN 978-4-89974-231-9 (Print) ISBN 978-4-89974-232-6 (PDF) The views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), its Advisory Council, ADB’s Board or Governors, or the governments of ADB members. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. ADBI uses proper ADB member names and abbreviations throughout and any variation or inaccuracy, including in citations and references, should be read as referring to the correct name. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “recognize,” “country,” or other geographical names in this publication, ADBI does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works without the express, written consent of ADBI. ADB recognizes “China” as the People’s Republic of China; “Korea” as the Republic of Korea; “Kyrgyzstan” as the Kyrgyz Republic; and “Vietnam” as Viet Nam. Note: In this publication, “$” refers to US dollars. Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building 8F 3-2-5, Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan www.adbi.org Contents Tables and Figures iv Abbreviations ix Contributors x Introduction 1 Naoyuki Yoshino, Bihong Huang, Dina Azhgaliyeva, and Qaisar Abbas 1. -

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre Berlin, 22 Januar 2019 Dear

UZBEK-GERMAN FORUM FOR HUMAN RIGHTS E.V. Oppelner str. 48-49 10997 Berlin +49 (0)176 3120 2474 [email protected] www.uzbekgermanforum.org Business & Human Rights Resource Centre Berlin, 22 Januar 2019 Dear Ms Skybenko, On behalf of the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights (UGF), I am writing to draw your attention to the systemic use of forced labour by the Uzbek-Spanish joint ventures Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos- Maxam, located respectively in the cities of Chirchiq and Almalyk in the Tashkent region of Uzbekistan. Every year, employees from Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam are forcibly sent to pick cotton for up to two months during the harvest. This often involves living and working in inappropriate conditions, away from their families, with inadequate food, water and sanitary facilities. Employees risk dismissal from their jobs for refusal to pick cotton and many who speak to journalists and human rights activists are unwilling to reveal their names for fear of reprisals by their employers. Our research has found that forced labour at Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam is not limited to picking cotton. In the summer of 2018, 120 employees of Maxam-Chirchiq were forced to go to the city of Akhangaran every day (located 82 km from Chirchiq) to work on demolishing buildings and clearing construction waste. Employees of Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam have been forcibly mobilised to harvest cotton every autumn for many years under orders of the Government of Uzbekistan. We are aware of two deaths of employees of Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam related to work in the cotton fields during the harvests of 2014 and 2018. -

Essential Fact36 2020 (PDF, 973.8

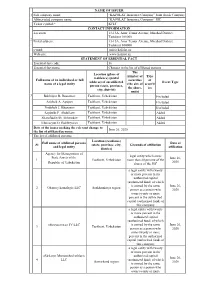

NAME OF ISSUER 1 Full company name: “KAFOLAT Insurance Company” Joint Stock Company . Abbreviated company name: “KAFOLAT Insurance Company” JSC Ticker symbol:* KFLT CONTACT INFORMATION Location: 13-13A, Amir Temur Avenue, Mirabad District, Tashkent 100000 2 Postal address: 13-13A, Amir Temur Avenue, Mirabad District, . Tashkent 100000 e-mail: [email protected] Web-site: www.kafolat.uz STATEMENT OF ESSENTIAL FACT Essential fact code: 36 Essential fact name: Changes in the list of affiliated persons The Location (place of number of Type residence) (postal Full name of an individual or full securities of address) of an affiliated Event Type name of a legal entity (the size of securit person (state, province, the share, ies city, district) units) 3 Bakhtiyor R. Rustamov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Excluded . Azizbek A. Ayupov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Excluded Nodirbek J. Khusanov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Excluded Saydullo P. Abdullaev Tashkent, Uzbekistan Added Sharofiddin Sh.Akhmedov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Added Khumoyun O. Bakhtiyorov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Added Date of the issuer making the relevant change to June 26, 2020 the list of affiliated persons: The list of affiliated persons: Location (residence) Full name of affiliated persons Date of № (state, province, city, Grounds of affiliation and legal entity affiliation district) Agency for Management of legal entity which owns State Assets of the June 26, 1 Tashkent, Uzbekistan more than 20 percent of the 2020 Republic of Uzbekistan shares of the JSC a legal entity with twenty or more percent in the authorized -

Download 349.51 KB

i Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Final Report April 2015 UZB: Housing for Integrated Rural Development Investment Program Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit under the Ministry of Economy for the Republic of Uzbekistan and The Asian Development Bank ii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence Review EIA Environmental Impact Assessment Housing for Integrated Rural Development HIRD Investment Program State committee for land resources, geodesy, SCLRGCSC cartography and state cadastre SCAC State committee of architecture and construction NPC Nature Protection Committee MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources QQB Qishloq Qurilish Bank QQI Qishloq Qurilish Invest This Due Diligence Report on Environmental and Social Safeguards is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 4 B. SUMMARY FINDINGS .................................................................................................. 4 C. SAFEGUARD STANDARDS -

Climate-Proofing Cooperation in the Chu and Talas River Basins

Climate-proofing cooperation in the Chu and Talas river basins Support for integrating the climate dimension into the management of the Chu and Talas River Basins as part of the Enhancing Climate Resilience and Adaptive Capacity in the Transboundary Chu-Talas Basin project, funded by the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs under the FinWaterWei II Initiative Geneva 2018 The Chu and Talas river basins, shared by Kazakhstan and By way of an integrated consultative process, the Finnish the Kyrgyz Republic in Central Asia, are among the few project enabled a climate-change perspective in the design basins in Central Asia with a river basin organization, the and activities of the GEF project as a cross-cutting issue. Chu-Talas Water Commission. This Commission began to The review of climate impacts was elaborated as a thematic address emerging challenges such as climate change and, annex to the GEF Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, to this end, in 2016 created the dedicated Working Group on which also included suggestions for adaptation measures, Adaptation to Climate Change and Long-term Programmes. many of which found their way into the Strategic Action Transboundary cooperation has been supported by the Programme resulting from the project. It has also provided United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) the Commission and other stakeholders with cutting-edge and other partners since the early 2000s. The basins knowledge about climate scenarios, water and health in the are also part of the Global Network of Basins Working context of climate change, adaptation and its financing, as on Climate Change under the UNECE Convention on the well as modern tools for managing river basins and water Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and scarcity at the national, transboundary and global levels.