“Tashkent's Reforms Have Not

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPERATION SCHEME of the Executives of Sectors, Head Offices and Secretaries of Head Offices of Tashkent Region

OPERATION SCHEME of the Executives of Sectors, Head offices and secretaries of Head offices of Tashkent Region Sector 1 – Khokim’s Head office Sector 2 – Head office secretary of the Sector 3 –Head office secretary of the Sector 4 – Head office secretary of the secretary and location Prosecutor’s Office and location Department of Internal affairs (DIA) State Tax Inspectorate and location and location Khidoyatov Davron Abdulpattakhovich Samadov Salom Ismatovich Aripov Tokhir Tulkinovich Raimov Ravshan Isakjanovich KHOKIM OF THE REGION TASHKENT REGION PROSECUTOR MAIN DEPARTMENT OF INTERNAL STATE TAX INSPECTORATE OF HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: A. Eshbaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: М. Egamberdiev AFFAIRS OF TASHKENT REGION TASHKENT REGION Phone number: (98) 007-30-04 Phone number: (97) 733-57-37 HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: F. HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: E. Djumabaev Location: 1, Almalik city, Tashkent region. Location: 1, Tashkent yuli, Nurafshan city. Khamitov Phone number: (93) 398-54-34 Phone of the Head office: (70) 201-07-34 +6448 Phone number: (99) 301-70-77 Location: 79 A, Babur str., Tashkent. Location: Mevazor, Kuyichirchik region. Phone of the Head office: (78) 150-49-56 Phone of the Head office: (95) 476-75 -77 Saliyev Muzaffar Kholdorbolevich Mirzayev Fakhriddin Yusupovich Amanbaev Navruz Zokirjonovich Narkhodjaev Sanjar Rashidovich KHOKIM OF NURAFSHAN CITY PROSECUTOR OF NURAFSHAN CITY DIA OF NURAFSHAN CITY NURAFSHAN CITY STATE TAX HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: О. Erbaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: М.Shukrullaev HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: F. INSPECTORATE Phone number: (99) 823-67-72 Phone: (97) 911-77-10 Imankulov HEAD OFFICE SECRETARY: E. Igamnazarov Location: Tashkent yuli str., Nurafshan city. Location: 4A, Shon shukhrat str., Obod turmush Phone: (94) 631-49-37 Phone: (94) 930-03-73 CCU, Nurafshan city. -

Housing for Integrated Rural Development Improvement Program

i Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Final Report June 2015 UZB: Housing for Integrated Rural Development Investment Program Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit under the Ministry of Economy for the Republic of Uzbekistan and The Asian Development Bank ii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence Review EIA Environmental Impact Assessment Housing for Integrated Rural Development HIRD Investment Program State committee for land resources, geodesy, SCLRGCSC cartography and state cadastre SCAC State committee of architecture and construction NPC Nature Protection Committee MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources QQL Qishloq Qurilish Loyiha QQI Qishloq Qurilish Invest This Due Diligence Report on Environmental and Social Safeguards is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 B. SUMMARY FINDINGS ............................................................................................... 4 C. SAFEGUARD STANDARDS ...................................................................................... -

Uzbekistan: Tashkent Province Sewerage Improvement Project

Initial Environmental Examination May 2021 Uzbekistan: Tashkent Province Sewerage Improvement Project Prepared by the Joint Stock Companies “Uzsuvtaminot” for the Asian Development Bank. ..Þ,zýUçâÛ,ÜINÞâ'' .,UzSUVTAMINoT" »KSIYADORLIK J°¼IY»ÂI JoINT ýâÞáÚ áÞÜà°ItÓr 1¾¾¾35, O'zbekiston Respublikasi l0OO35, Republic of Uzbekistan Toshkent shahri, Niyozbek yo'li ko'chasi 1-çã Tashkent ciý, Niyozbek 5ruli stÛÕÕt 1 apt. telefon: +998 55 5Þ3 l2 55 telephone: +998 55 503 12 55 uzst14,exat.uz, infcl(rtluzsuv. çz æzst{o exat. uz, iÛ[Þ(Ð æzsçç, æz _ 2 Ñ 1,1AÙ 202l Nq 4l2L 1 4 2 Ò ÂÞ: ¼r. Jung ½Þ ºim Project Officer SÕßiÞr UrÌÐß Development Specialist ÁÕßtrÐl and West Asia DÕàÐÓtmÕßt UrÌÐß Development and Water Division °siÐß Development ²Ðßk Subject: Project 52045-001 Tashkent ÀrÞçißáÕ Sewerage lmprovement Project - Revised lnitial Environmental Examination Dear ¼r. Kim, We hÕrÕÌà endorse the final revised and updated version of the lnitial µßvirÞßmÕßtÐl Examination (lEE) àrÕàÐrÕd fÞr the Tashkent ÀrÞçißáÕ Sewerage lmprovement ÀrÞjÕát. The lEE has ÌÕÕß discussed and reviewed Ìã the Projecls Coordination Unit ußdÕr JSc "UZSUVTAMlNoT". We ÕßSçrÕ, that the lEE will ÌÕ posted Þß the website of the JSC "UZSUVTAMlNoT" to ÌÕ available to the project affected àÕÞà|Õ, the printed áÞàã will also ÌÕ delivered to Ñ hokimiyats for disclosure to the local people. FuÓthÕr, hereby we submit the lEE to ADB for disclosure Þß the ÔD² website. Sincerely, Rusta janov Deputy irman of the Board CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 May 2021) Currency unit – Uzbekistan Sum (SUM) -

Development of Renewable Energy Sources in Uzbekistan

Renewable Energy Bekzod Asadov, Ministry of Energy, in Uzbekistan Republic of Uzbekistan Tashkent 2021 Power sector – fuel sources Mineral resource diversity excludes the dependence Energy supply on a single resource type diversification by source Hydropower Natural gas Uranium Coal Investments of USD 2.7 bn in 2017–2025 to develop 18 new projects and upgrade 14 existing plants Place in world 24th 16th 29th reserves Solar 51 bln tons of oil equivalent Place in world 13th 7th 34th Wind Production 360 mln tons of oil equivalent for wind energy 2 Government’s recent power sector reforms Electricity market models and transition stages identified JSC “Thermal power Together with experts from JSC “Uzbekhydroenergo” the WB, ADB and EBRD, a plants” ~ Total installed capacity: 1 new version of the ~ Total installed capacity: 13 Electricity Law is being 932 MW 415 MW developed The Electricity Grid Code is being developed with technical support from the World Bank JSC “Uzbekenergo” JSC “Regional Electric JSC “National Electric Grids of Uzbekistan” Network of Uzbekistan” The Concept for the Distribution and supply of Transportation of electrical provision of the Republic of Uzbekistan with electric electrical energy to energy from generation energy for 2020-2030 was consumers through sources through high voltage developed distribution networks. networks Transition to IEC standards in progress 4 Uzbekistan’s Development plans of RES Gas fired old Gas fired new Hydro Due to active measures for the development Coal fired Solar PV Wind of renewables and the construction of Nuclear Load balancers, gas Isolated stations 0.13 nuclear power plant the consumption of 1.31 natural gas by TPP is expected to decrease 2.40 up to 25% in 2030, despite of the increasing 3.00 electricity generation to 75%. -

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre Berlin, 22 Januar 2019 Dear

UZBEK-GERMAN FORUM FOR HUMAN RIGHTS E.V. Oppelner str. 48-49 10997 Berlin +49 (0)176 3120 2474 [email protected] www.uzbekgermanforum.org Business & Human Rights Resource Centre Berlin, 22 Januar 2019 Dear Ms Skybenko, On behalf of the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights (UGF), I am writing to draw your attention to the systemic use of forced labour by the Uzbek-Spanish joint ventures Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos- Maxam, located respectively in the cities of Chirchiq and Almalyk in the Tashkent region of Uzbekistan. Every year, employees from Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam are forcibly sent to pick cotton for up to two months during the harvest. This often involves living and working in inappropriate conditions, away from their families, with inadequate food, water and sanitary facilities. Employees risk dismissal from their jobs for refusal to pick cotton and many who speak to journalists and human rights activists are unwilling to reveal their names for fear of reprisals by their employers. Our research has found that forced labour at Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam is not limited to picking cotton. In the summer of 2018, 120 employees of Maxam-Chirchiq were forced to go to the city of Akhangaran every day (located 82 km from Chirchiq) to work on demolishing buildings and clearing construction waste. Employees of Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam have been forcibly mobilised to harvest cotton every autumn for many years under orders of the Government of Uzbekistan. We are aware of two deaths of employees of Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam related to work in the cotton fields during the harvests of 2014 and 2018. -

Fayaz Tepa Surkhan Darya Region Uzbekistan

MINIstrY OF CULTUre - BOarD OF MONUments - UNESCO / JAPan FIT fAYAZ tEPA SURKHan DarYA RegION UZBEKIstan A CRATerre-ENSAG PUBLIcatION MINIstrY OF CULTUre - BOarD OF MONUments - UNESCO / JAPan FIT fAYAZ tEPA SURKHan DarYA RegION UZBEKIstan NOVemBer 2006 A CRATerre-ENSAG PUBLIcatION FOREWORD Located at the crossroads of the ancient Steppe Route Generously funded by the Japanese Government, the Fayaz-Tepa L and Silk Road, Central Asia possesses a rich cultural project aims, first and foremost, to conserve the ancient earthen heritage, offering a living testimony to thousands of structures for the purpose of safeguarding and displaying them. years of history and to the unique contributions of an astounding Related activities carried out in the framework of the project variety of peoples and cultures. The region’s present population include training, documentation and research, the creation of is a mosaic of these diverse influences, and its deep-rooted and a site museum, and the elaboration of a master plan for the multifarious cultural identity has been forged, in great measure, management of the cultural resources of the Termez region. by this diversity. From 2000 to 2006, an interdisciplinary team of international experts, working hand-in-hand with their Uzbek colleagues, In recent years, UNESCO has undertaken several challenging have introduced state-of-the-art conservation methods, projects for the preservation of Central Asia’s precious cultural involving applied research, materials testing and painstaking heritage, as part of its overriding goal of safeguarding the documentation work. This has resulted in the transfer to the world’s cultural diversity. Our strategy in this domain has been host country of scientific knowledge and modern, up-to-date to help re-establish links between present-day populations and conservation techniques and practices, which can be employed their traditions and cultural history, with a view to building a in future restoration projects in Uzbekistan and the region. -

51041-002: Horticulture Value Chain Infrastructure Project

Horticulture Value Chain Infrastructure Project (RRP UZB 51041) Initial Environmental Examination Project number: 51041-002 September 2018 Draft UZB: Horticulture Value Chain Infrastructure Project Andijan Agro-Logistic Center Prepared by the Rural Reconstruction Agency (RRA), Republic of Uzbekistan for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................ii GLOSSARY .......................................................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 7 2. POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK AND STANDARDS ................. 8 2.1. Institutional -

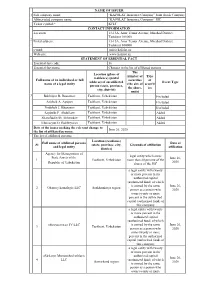

Essential Fact36 2020 (PDF, 973.8

NAME OF ISSUER 1 Full company name: “KAFOLAT Insurance Company” Joint Stock Company . Abbreviated company name: “KAFOLAT Insurance Company” JSC Ticker symbol:* KFLT CONTACT INFORMATION Location: 13-13A, Amir Temur Avenue, Mirabad District, Tashkent 100000 2 Postal address: 13-13A, Amir Temur Avenue, Mirabad District, . Tashkent 100000 e-mail: [email protected] Web-site: www.kafolat.uz STATEMENT OF ESSENTIAL FACT Essential fact code: 36 Essential fact name: Changes in the list of affiliated persons The Location (place of number of Type residence) (postal Full name of an individual or full securities of address) of an affiliated Event Type name of a legal entity (the size of securit person (state, province, the share, ies city, district) units) 3 Bakhtiyor R. Rustamov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Excluded . Azizbek A. Ayupov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Excluded Nodirbek J. Khusanov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Excluded Saydullo P. Abdullaev Tashkent, Uzbekistan Added Sharofiddin Sh.Akhmedov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Added Khumoyun O. Bakhtiyorov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Added Date of the issuer making the relevant change to June 26, 2020 the list of affiliated persons: The list of affiliated persons: Location (residence) Full name of affiliated persons Date of № (state, province, city, Grounds of affiliation and legal entity affiliation district) Agency for Management of legal entity which owns State Assets of the June 26, 1 Tashkent, Uzbekistan more than 20 percent of the 2020 Republic of Uzbekistan shares of the JSC a legal entity with twenty or more percent in the authorized -

Free Movement and Affordable Housing

Policy Research Working Paper 9107 Public Disclosure Authorized Free Movement and Affordable Housing Public Preferences for Reform in Uzbekistan Public Disclosure Authorized William Seitz Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Poverty and Equity Global Practice January 2020 Policy Research Working Paper 9107 Abstract Uzbekistan has one of the lowest rates of internal migration The results show that about 90 percent of people support in the world, leading to persistent economic imbalances. lifting all registration restrictions and over 80 percent favor Drawing from a unique monthly panel survey called Listen- increasing urban housing construction. The results of the ing to the Citizens of Uzbekistan and a survey experiment, experiment show that reform popularity increases when this paper focuses on two factors that prevent domestic propiska rules and housing costs are referenced in randomly mobility: (i) restrictive propiska registration policies, and assigned vignettes. However, views may also be sensitive (ii) the exceptionally high cost of urban housing. Registra- to perceptions of fairness. Recent high-profile involun- tion rules prohibit migration to urban centers, and urban tary demolitions coincided with a doubling of the share housing costs push up the cost of living to as much as 550 responding that policies are unfair. The increase was fur- percent of the national average, levels severely unaffordable ther associated with declining optimism and lower support for almost all rural residents. But the proposed government for the wider government national development program, reforms in 2019 to address these challenges are very popular. beyond urbanization issues. This paper is a product of the Poverty and Equity Global Practice. -

Delivery Destinations

Delivery Destinations 50 - 2,000 kg 2,001 - 3,000 kg 3,001 - 10,000 kg 10,000 - 24,000 kg over 24,000 kg (vol. 1 - 12 m3) (vol. 12 - 16 m3) (vol. 16 - 33 m3) (vol. 33 - 82 m3) (vol. 83 m3 and above) District Province/States Andijan region Andijan district Andijan region Asaka district Andijan region Balikchi district Andijan region Bulokboshi district Andijan region Buz district Andijan region Djalakuduk district Andijan region Izoboksan district Andijan region Korasuv city Andijan region Markhamat district Andijan region Oltinkul district Andijan region Pakhtaobod district Andijan region Khdjaobod district Andijan region Ulugnor district Andijan region Shakhrikhon district Andijan region Kurgontepa district Andijan region Andijan City Andijan region Khanabad City Bukhara region Bukhara district Bukhara region Vobkent district Bukhara region Jandar district Bukhara region Kagan district Bukhara region Olot district Bukhara region Peshkul district Bukhara region Romitan district Bukhara region Shofirkhon district Bukhara region Qoraqul district Bukhara region Gijduvan district Bukhara region Qoravul bazar district Bukhara region Kagan City Bukhara region Bukhara City Jizzakh region Arnasoy district Jizzakh region Bakhmal district Jizzakh region Galloaral district Jizzakh region Sh. Rashidov district Jizzakh region Dostlik district Jizzakh region Zomin district Jizzakh region Mirzachul district Jizzakh region Zafarabad district Jizzakh region Pakhtakor district Jizzakh region Forish district Jizzakh region Yangiabad district Jizzakh region -

World Bank Document

Ministry of Agriculture and Uzbekistan Agroindustry and Food Security Agency (UZAIFSA) Public Disclosure Authorized Uzbekistan Agriculture Modernization Project Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Tashkent, Uzbekistan December, 2019 ABBREVIATIONS AND GLOSSARY ARAP Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan CC Civil Code DCM Decree of the Cabinet of Ministries DDR Diligence Report DMS Detailed Measurement Survey DSEI Draft Statement of the Environmental Impact EHS Environment, Health and Safety General Guidelines EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ES Environmental Specialist ESA Environmental and Social Assessment ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FS Feasibility Study GoU Government of Uzbekistan GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism H&S Health and Safety HH Household ICWC Integrated Commission for Water Coordination IFIs International Financial Institutions IP Indigenous People IR Involuntary Resettlement LAR Land Acquisition and Resettlement LC Land Code MCA Makhalla Citizen’s Assembly MoEI Ministry of Economy and Industry MoH Ministry of Health NGO Non-governmental organization OHS Occupational and Health and Safety ОP Operational Policy PAP Project Affected Persons PCB Polychlorinated Biphenyl PCR Physical Cultural Resources PIU Project Implementation Unit POM Project Operational Manual PPE Personal Protective Equipment QE Qishloq Engineer -

Enhancing the Efficiency of Power Supply to the Consumers in Rural and Remote Areas by Providing the Access to Energy Resources

ENHANCING THE EFFICIENCY OF POWER SUPPLY TO THE CONSUMERS IN RURAL AND REMOTE AREAS BY PROVIDING THE ACCESS TO ENERGY RESOURCES AND SERVICES, AND BY IMPLEMENTING THE ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES IN THE RENEWABLE ENERGY SECTOR IN UZBEKISTAN INTRODUCTION. Over the past twenty years, the Republic of Uzbekistan, as a result of diversification and modernization of the economy, has established itself as a developed country in the Central Asian region. The republic overcame difficulties of the transition period, the international financial- economic crisis and maintains dynamic GDP growth, which in the last six years is more than 8 percent. According to the estimates of international financial institutions, the same high rates of economic growth will persist in the near perspective. President of the Republic of Uzbekistan, Islam Karimov, in his speech at the 6th meeting of the Asia Solar Energy Forum in Tashkent (in 2013) noted that country’s needs in the electric energy will increase in the year 2030 by approximately twofold compared to this year’s indicators and will exceed 105 billion kilowatt hours, taking into account the high advancing development rates in the manufacturing industry and the need to develop the agricultural sector. In this context, taking into account the need to improve the quality of population life, the need arises to analyze and find ways to reliable access to energy resources and services in rural areas, more than 80 percent of the country's vast territory. This would be consistent with a global UN initiative “Sustainable Energy for All”, which provides achieving the following inter-linked objectives by 2030: Ensuring universal access to modern and environmental friendly energy resources; Doubling the rate of improvement in energy efficiency; Doubling the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix.