Thesis Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status of Russian Ethnic Minority in Independent Tajikistan

Status of Russian Ethnic Minority in Independent Tajikistan DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of Kashmir in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy (M. Phil) In History By Farooq Ahmad Rather Under the Supervision of Prof. Aijaz A. Bandey CENTRE OF CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES University of Kashmir, Srinagar- 190006 JAMMU AND KASHMIR, INDIA September, 2012 Centre of Central Asian Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar “A” Grade NAAC Accredited CERTIFICATE Certified that the thesis entitled “Status of Russian Ethnic Minority in Independent Tajikistan” submitted by Farooq Ahmad Rather for the Degree of M. Phil in the discipline of History is an original piece of research work. This work has not been submitted fully or partially so far anywhere for the award of any degree. The scholar worked under my supervision on whole time basis for the period required under statues and has put in the required attendance in the Centre. Prof. Aijaz A. Bandey (Supervisor) Countersigned (Prof. G. R. Jan) Director Declaration I solemnly declare that the Dissertation entitled “Status of Russian Ethnic Minority in Independent Tajikistan” submitted by me in the discipline of History under the supervision of Prof. Aijaz A. Bandey embodies my own contribution. This work, which does not contain piracy, has not been submitted, so far, anywhere for the award of any degree. Dated Signature 5 October 2012 Farooq Ahmad Rather CCAS University of Kashmir, Srinagar CONTENTS Page No. Preface i Chapter-I Introduction 1 -

Housing for Integrated Rural Development Improvement Program

i Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Final Report June 2015 UZB: Housing for Integrated Rural Development Investment Program Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit under the Ministry of Economy for the Republic of Uzbekistan and The Asian Development Bank ii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence Review EIA Environmental Impact Assessment Housing for Integrated Rural Development HIRD Investment Program State committee for land resources, geodesy, SCLRGCSC cartography and state cadastre SCAC State committee of architecture and construction NPC Nature Protection Committee MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources QQL Qishloq Qurilish Loyiha QQI Qishloq Qurilish Invest This Due Diligence Report on Environmental and Social Safeguards is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 4 B. SUMMARY FINDINGS ............................................................................................... 4 C. SAFEGUARD STANDARDS ...................................................................................... -

The University of Chicago Old Elites Under Communism: Soviet Rule in Leninobod a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Di

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OLD ELITES UNDER COMMUNISM: SOVIET RULE IN LENINOBOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY FLORA J. ROBERTS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables ...................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi A Note on Transliteration .................................................................................................. ix Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One. Noble Allies of the Revolution: Classroom to Battleground (1916-1922) . 43 Chapter Two. Class Warfare: the Old Boi Network Challenged (1925-1930) ............... 105 Chapter Three. The Culture of Cotton Farms (1930s-1960s) ......................................... 170 Chapter Four. Purging the Elite: Politics and Lineage (1933-38) .................................. 224 Chapter Five. City on Paper: Writing Tajik in Stalinobod (1930-38) ............................ 282 Chapter Six. Islam and the Asilzodagon: Wartime and Postwar Leninobod .................. 352 Chapter Seven. The -

Birth of Tajikistan : National Identity and the Origins of the Republic

THE BIRTH OF TAJIKISTAN i THE BIRTH OF TAJIKISTAN ii THE BIRTH OF TAJIKISTAN For Suzanne Published in 2007 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States of America and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan a division of St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Paul Bergne The right of Paul Bergne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. International Library of Central Asian Studies 1 ISBN: 978 1 84511 283 7 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd From camera-ready copy edited and supplied by the author THE BIRTH OF TAJIKISTAN v CONTENTS Abbreviations vii Transliteration ix Acknowledgements xi Maps. Central Asia c 1929 xii Central Asia c 1919 xiv Introduction 1 1. Central Asian Identities before 1917 3 2. The Turkic Ascendancy 15 3. The Revolution and After 20 4. The Road to Soviet Power 28 5. -

Women in Uzbekistan Prepared in 1999 by Dinara Alimdjanova, Former Gender Specialist at ADB’S Uzbekistan Resident Mission

Country Briefing Paper Women in the Republic of Uzbekistan Prepared by Wendy Mee FEBRUARY 2001 Acknowledgments This Country Briefing Paper on the status of Women in the Republic of Uzbekistan would not have been possible without the assistance and guidance of many people. In particular, I must thank Mekhri Khudayberdiyeva from ADB’s Resident Mission in Uzbekistan. Ms. Khudayberdiyeva proved a valuable research colleague, whose fluency in Russian, Uzbek and English, and organizational skills made the research possible. Furthermore, her good judgment and sense of humor made the research highly enjoyable. The report also benefited from her very helpful feedback on the draft report and her help in the preparation of the two appendices. I also owe a debt of gratitude to all the people in Uzbekistan who gave so generously of their time and experience. In particular, I would like to thank those who allowed me to interview them, observe training days, or participate in other related activities. I would also like to thank the participants of the Gender and Development consultative meeting held at ADB’s Resident Mission in Tashkent on 16 November 2000. I am deeply grateful to the following individuals: Dilbar Gulyamova (Deputy Prime Minister, Republic of Uzbekistan) Dilovar Kabulova (Women’s Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan) Sayora Khodjaeva (Deputy Hokim, Tashkent Oblast) Nariman Mannapbekov (Cabinet of Ministries) Galina Saidova (Cabinet of Ministries) Gasanov M. and Jurayeva Feruza Tulkunovna (Institute for Monitoring Acting Legislation -

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre Berlin, 22 Januar 2019 Dear

UZBEK-GERMAN FORUM FOR HUMAN RIGHTS E.V. Oppelner str. 48-49 10997 Berlin +49 (0)176 3120 2474 [email protected] www.uzbekgermanforum.org Business & Human Rights Resource Centre Berlin, 22 Januar 2019 Dear Ms Skybenko, On behalf of the Uzbek-German Forum for Human Rights (UGF), I am writing to draw your attention to the systemic use of forced labour by the Uzbek-Spanish joint ventures Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos- Maxam, located respectively in the cities of Chirchiq and Almalyk in the Tashkent region of Uzbekistan. Every year, employees from Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam are forcibly sent to pick cotton for up to two months during the harvest. This often involves living and working in inappropriate conditions, away from their families, with inadequate food, water and sanitary facilities. Employees risk dismissal from their jobs for refusal to pick cotton and many who speak to journalists and human rights activists are unwilling to reveal their names for fear of reprisals by their employers. Our research has found that forced labour at Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam is not limited to picking cotton. In the summer of 2018, 120 employees of Maxam-Chirchiq were forced to go to the city of Akhangaran every day (located 82 km from Chirchiq) to work on demolishing buildings and clearing construction waste. Employees of Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam have been forcibly mobilised to harvest cotton every autumn for many years under orders of the Government of Uzbekistan. We are aware of two deaths of employees of Maxam-Chirchiq and Ammofos-Maxam related to work in the cotton fields during the harvests of 2014 and 2018. -

Essential Fact36 2020 (PDF, 973.8

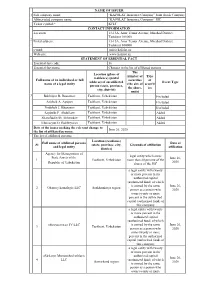

NAME OF ISSUER 1 Full company name: “KAFOLAT Insurance Company” Joint Stock Company . Abbreviated company name: “KAFOLAT Insurance Company” JSC Ticker symbol:* KFLT CONTACT INFORMATION Location: 13-13A, Amir Temur Avenue, Mirabad District, Tashkent 100000 2 Postal address: 13-13A, Amir Temur Avenue, Mirabad District, . Tashkent 100000 e-mail: [email protected] Web-site: www.kafolat.uz STATEMENT OF ESSENTIAL FACT Essential fact code: 36 Essential fact name: Changes in the list of affiliated persons The Location (place of number of Type residence) (postal Full name of an individual or full securities of address) of an affiliated Event Type name of a legal entity (the size of securit person (state, province, the share, ies city, district) units) 3 Bakhtiyor R. Rustamov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Excluded . Azizbek A. Ayupov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Excluded Nodirbek J. Khusanov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Excluded Saydullo P. Abdullaev Tashkent, Uzbekistan Added Sharofiddin Sh.Akhmedov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Added Khumoyun O. Bakhtiyorov Tashkent, Uzbekistan Added Date of the issuer making the relevant change to June 26, 2020 the list of affiliated persons: The list of affiliated persons: Location (residence) Full name of affiliated persons Date of № (state, province, city, Grounds of affiliation and legal entity affiliation district) Agency for Management of legal entity which owns State Assets of the June 26, 1 Tashkent, Uzbekistan more than 20 percent of the 2020 Republic of Uzbekistan shares of the JSC a legal entity with twenty or more percent in the authorized -

Download 349.51 KB

i Due Diligence Report on Environment and Social Safeguards Final Report April 2015 UZB: Housing for Integrated Rural Development Investment Program Prepared by: Project Implementation Unit under the Ministry of Economy for the Republic of Uzbekistan and The Asian Development Bank ii ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence Review EIA Environmental Impact Assessment Housing for Integrated Rural Development HIRD Investment Program State committee for land resources, geodesy, SCLRGCSC cartography and state cadastre SCAC State committee of architecture and construction NPC Nature Protection Committee MAWR Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources QQB Qishloq Qurilish Bank QQI Qishloq Qurilish Invest This Due Diligence Report on Environmental and Social Safeguards is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 4 B. SUMMARY FINDINGS .................................................................................................. 4 C. SAFEGUARD STANDARDS -

Climate-Proofing Cooperation in the Chu and Talas River Basins

Climate-proofing cooperation in the Chu and Talas river basins Support for integrating the climate dimension into the management of the Chu and Talas River Basins as part of the Enhancing Climate Resilience and Adaptive Capacity in the Transboundary Chu-Talas Basin project, funded by the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs under the FinWaterWei II Initiative Geneva 2018 The Chu and Talas river basins, shared by Kazakhstan and By way of an integrated consultative process, the Finnish the Kyrgyz Republic in Central Asia, are among the few project enabled a climate-change perspective in the design basins in Central Asia with a river basin organization, the and activities of the GEF project as a cross-cutting issue. Chu-Talas Water Commission. This Commission began to The review of climate impacts was elaborated as a thematic address emerging challenges such as climate change and, annex to the GEF Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, to this end, in 2016 created the dedicated Working Group on which also included suggestions for adaptation measures, Adaptation to Climate Change and Long-term Programmes. many of which found their way into the Strategic Action Transboundary cooperation has been supported by the Programme resulting from the project. It has also provided United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) the Commission and other stakeholders with cutting-edge and other partners since the early 2000s. The basins knowledge about climate scenarios, water and health in the are also part of the Global Network of Basins Working context of climate change, adaptation and its financing, as on Climate Change under the UNECE Convention on the well as modern tools for managing river basins and water Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and scarcity at the national, transboundary and global levels. -

Bitiruv Malakaviy Ishi

O’ZBЕKISTON RЕSPUBLIKASI OLIY VA O’RTA MAXSUS TA’LIM VAZIRLIGI NAMANGAN MUHANDISTLIK-QURILISH INSTITUTI “QURILISH” fakulteti “BINOLAR VA INSHOOTLAR QURILISHI” kafedrasi САМАТОВ АБДУМУТАЛ АБДУҚОДИР ЎҒЛИ ” Angren shaharida xududa namunaviy kam-qavatli turar- joy uylarini loyihasini me`moray rejalashtirish ” 5341000 «Qishloq hududlarini arxitektura-loyihaviy tashkil etish» Bakalavr darajasini olish uchun yozilgan BITIRUV MALAKAVIY ISHI Kafedra mudiri: dots.S.Abduraxmonov___________ Ilmiy rahbar: , к.ўқ A.Dadaboyev ___________ “_____”___________2018 y Namangan 2018 Kirish. O'zbekiston Respublikasi mustaqillikka erishgan davrdan boshlab hukumatimiz tomonidan arhitektura va shaharsozlik sohasiga katta e‘tibor berilib, shaharsozlik sohasi faoliyatida bir qator O'zbekiston Respublikasi Birinchi Prezidenti Farmonlari va Vazirlar Maxkamasining ushbu soha yuzasidan qarorlari qabul qilindi. O'zbekiston Respublikasi Birinchi Prezidentining ―O'zbekiston Respublikasida Arhitektura va shahar qurilishini yanada takomillashtirish chora- tadbirlari to'g'risida‖gi farmoni hamda ushbu farmon ijrosi yuzasidan Vazirlar Mahkamasining ―Arhitektura va qurilish sohasidagi ishlarni tashkil etish va nazoratni takomillashtirish chora-tadbirlari to'g'risida‖gi, ―Shaharlar, tuman markazlari va shahar tipidagi posyolkalarning bosh rejalarini ishlab chiqish va ularni qurish tartibi to'g'risidagi Nizomni tasdiqlash xaqida‖gi, ―Arhitektura va shaharsozlik sohasidagi qonun hujjatlariga rioya qilinishi uchun rahbarlar va mansabdor shahslarning javobgarligini oshirish chora-tadbirlari -

Policy Briefing

Policy Briefing Asia Briefing N°54 Bishkek/Brussels, 6 November 2006 Uzbekistan: Europe’s Sanctions Matter I. OVERVIEW in their production, or to the national budget, but to the regime itself and its key allies, particularly those in the security services. Perhaps motivated by an increasing After the indiscriminate killing of civilians by Uzbek sense of insecurity, the regime has begun looting some security forces in the city of Andijon in 2005, the of its foreign joint-venture partners. Shuttle trading and European Union imposed targeted sanctions on the labour migration to Russia and Kazakhstan are increasingly government of President Islam Karimov. EU leaders threatened economic lifelines for millions of Uzbeks. called for Uzbekistan to allow an international investigation into the massacre, stop show trials and improve its human Rather than take serious measures to improve conditions, rights record. Now a number of EU member states, President Karimov has resorted to scapegoating and principally Germany, are pressing to lift or weaken the cosmetic changes, such as the October 2006 firing of sanctions, as early as this month. The Karimov government Andijon governor Saydullo Begaliyev, whom he has has done nothing to justify such an approach. Normalisation publicly called partially responsible for the previous of relations should come on EU terms, not those of year’s events. On the whole, however, Karimov continues Karimov. Moreover, his dictatorship is looking increasingly to deny that his regime’s policies were in any way at fragile, and serious thought should be given to facing the fault, while the same abuses are unchecked in other consequences of its ultimate collapse, including the impact provinces. -

The Aral Sea Basin Is Located in the Centre of Eurasian Continent And

The Aral Sea Basin is located in the centre of Eurasian continent and covers the territory of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, major part of Turkmenistan, part of Kyrgyzstan, southern part of Kazakhstan and northern part of Afghanistan. Water resources of the Aral Sea basin are formed in surface and underground sources and glaciers. Surface waters are mainly concentrated in the basins of the two main rivers of the region –Amudarya and Syrdarya. Independent hydrographic basins (gravitating towards the Amudarya and Syrdarya rivers) create Kashkadarya, Zaravshan, Murgab, Tedjen, Chu, Talas rivers that lost connection with the main rivers many centuries ago. The territory can be divided to three main zones on the conditions of formation and transformation of the surface flow in the region: • zone, where the flow is formed (area of feeding in mountainous regions); • zone of transit and dispersion of flow; • delta zones. Numerous glaciers are concentrated in the mountain systems of the Central Asia, which give rise to practically all large rivers of the region, the water of which is intensively used in the national economy. The major part of glaciers is located in the territory of the Republic of Tajikistan and the Republic of Kyrgyzstan. On the whole, water resources in the Aral Sea basin are not equally distributed. 55,4% of the flow in the basin are formed within the territory of Tajikistan, in Kyrgyzstan – 25,3%, in Uzbekistan – 7,6%, in Kazakhstan – 3,9%, in Turkmenistan – 2,4%, on the territory of Afghanistan and other countries, share of which is not significant (China, Pakistan) – around 5,4% of the flow is formed.