UNIVERSITY of CALGARY Mocking Hitler: Nazi Speech & Humour In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Die Figuren des Helmut Qualtinger in der Tradition des Wiener Volksstücks“ Verfasser Elias Natmessnig angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. A 317 Studienblatt: Studienrichtung lt. Theater- Film- und Medienwissenschaften Studienblatt: Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Christian Schulte 1 2 Inhalt Inhalt........................................................................................................................................... 3 1) Einleitung............................................................................................................................... 7 2) Inspirationen der Jugend...................................................................................................... 10 3) Das Volksstück .................................................................................................................... 15 3.1) Das Wiener Volksstück................................................................................................. 18 3.1.1) Johann Nepomuk Nestroy...................................................................................... 19 3.1.2) Zwischen Nestroy und Kraus................................................................................. 22 3.1.3) Karl Kraus.............................................................................................................. 24 3.2) Die Erneuerer ............................................................................................................... -

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES in ISLAM

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES IN ISLAM Editiorial Board Baderin, Mashood, SOAS, University of London Fadil, Nadia, KU Leuven Goddeeris, Idesbald, KU Leuven Hashemi, Nader, University of Denver Leman, Johan, GCIS, emeritus, KU Leuven Nicaise, Ides, KU Leuven Pang, Ching Lin, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Platti, Emilio, emeritus, KU Leuven Tayob, Abdulkader, University of Cape Town Stallaert, Christiane, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Toğuşlu, Erkan, GCIS, KU Leuven Zemni, Sami, Universiteit Gent Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century Benjamin Nickl Leuven University Press Published with the support of the Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand University of Sydney and KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © Benjamin Nickl, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. The licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non- commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: B. Nickl. 2019. Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment: Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licences -

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-14571-8 - German Intellectuals and the Nazi Past A. Dirk Moses Excerpt More information Introduction The proposition that the Federal Republic of Germany has developed a healthy democratic culture centered around memory of the Holocaust has almost become a platitude.1 Symbolizing the relationship between the Federal Repub- lic’s liberal political culture and honest reckoning with the past, an enormous Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe adjacent to the Bundestag (Federal Parliament) and Brandenburg Gate in the national capital was unveiled in 2005. States usually erect monuments to their fallen soldiers, after all, not to the vic- tims of these soldiers. In the eyes of many, the West German and, since 1990, the united German experience has become the model of how post-totalitarian and postgenocidal societies “come to terms with the past.”2 Germany now seemed no different from the rest of Europe – or, indeed, from the West generally. Jews from Eastern Europe are as happy to settle there as they are to emigrate to Israel, the United States, or Australia.3 1 Bill Niven, Facing the Nazi Past: United Germany and the Legacy of the Third Reich (London and New York, 2002). For an excellent overview of postwar memory politics, see Andrew H. Beattie, “The Past in the Politics of Divided and Unified Germany,” in Max Paul Friedman and Padraic Kenney, eds., Partisan Histories: The Past in Contemporary Global Politics (Houndmills, 2005), 17–38. 2 For example, Daniel J. Goldhagen, “Modell Bundesrepublik: National History, Democracy and Internationalization in Germany,” Common Knowledge, 3 (1997), 10–18. -

Obama's Discourse of "Hope": Making Rhetoric Work Politically

Obama's discourse of "hope": Making rhetoric work politically Marcus Letts University of Bristol © Marcus Letts School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies University of Bristol Working Paper No. 04-09 Marcus Letts is a former undergraduate student in the Department of Politics, University of Bristol. This paper, originally a BSc dissertation, received the highest mark awarded to any BSc dissertation in Politics at the University of Bristol in 2008-2009. A revised version of this paper is currently being prepared for submission to the journal New Political Science. University of Bristol School of Sociology, Politics, and International Studies Title: Obama's discourse of "hope": Making rhetoric work politically (Morris, C. 2008) Question: What is articulated in Obama's discourse of "hope"? How did this rhetoric work politically? Marcus Letts Word Count: 9,899 2 Contents: Introduction: The US elections of 2008: A contextualisation The "strange death of Republican America": A grand theme of change................................ 5 A "rhetorical situation"?.......................................................................................................... 6 The birth of "Brand Obama": An exceptional campaign........................................................ 7 The nature of American "polyarchy"...................................................................................... 9 Literature Review: Two theories of discourse. Derrida's deconstruction and Laclau logics: A theory of discourse.......................................10 -

Whose Hi/Story Is It? the U.S. Reception of Downfall

Whose Hi/story Is It? The U.S. Reception of Downfall David Bathrick Before I address the U.S. media response to the fi lm Downfall, I would like to mention a methodological problem that I encountered time and again when researching this essay: whether it is possible to speak of reception in purely national terms in this age of globalization, be it a foreign fi lm or any other cultural artifact. Generally speaking, Bernd Eichinger’s large-scale production Downfall can be considered a success in America both fi nancially and critically. On its fi rst weekend alone in New York City it broke box-offi ce records for the small repertory movie theater Film Forum, grossing $24,220, despite its consider- able length, some two and a half hours, and the fact that it was shown in the original with subtitles. Nationally, audience attendance remained unusually high for the following twelve weeks, compared with average fi gures for other German fi lms made for export markets.1 Downfall, which grossed $5,501,940 to the end of October 2005, was an unequivocal box-offi ce hit. One major reason for its success was certainly the content. Adolf Hit- ler, in his capacity as star of the silver screen, has always been a suffi cient This article originally appeared in Das Böse im Blick: Die Gegenwart des Nationalsozialismus im Film, ed. Margrit Frölich, Christian Schneider, and Karsten Visarius (Munich: edition text und kritik, 2007). 1. The only more recent fi lm to earn equivalent revenue was Nirgendwo in Afrika. -

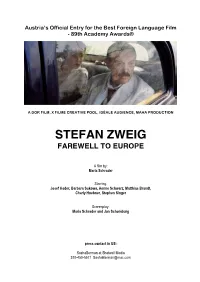

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

De Oratore I

D E O R A T O R E BO O" 1 TRA N S L A TED IN TO E N G LIS H W ITH A N IN T R O DU C TIO N B Y P E N . MOOR M . , . A . A S S I S T A N T M A S T E R A T C L I F T O N C O L L E G E filamj um a nti 1 8 BU RY S TREET W C , . L O N D O N 1 8 9 2 IN TR O D U C TIO N H T E t hre e b o o k s De Ora tore seem to have been B . C 5 5 written by Cicero in the year . It was n t o n s o f a time when, owi g the i crea ing power the fo r Triumvirs, there was little room any political activity o n o f his the part Cicero . On recall from exile in the preceding year he had conceived som e hopes o f again taking a leading part in political life but owing partly to the lukewarmness o f some and the downright faith o f o f lessness others his old supporters, which made it impossible for him to resume his o l d place at the head o f s ro the optimates, and partly to the clo er union p du ced between Pom peia s and Caesar by the conference s at Luca, he thought it more advi able to withdraw f m s a s inva ri ro public life and con ole himself, was his 1 w able custom , with literary work . -

List of Significant Historical Characters in Der Untergang / the Downfall

list of significant historical characters in Der Untergang / The Downfall Adolf Hitler (played by Bruno Ganz) Traudl Humps Junge (played by Alexandra Maria Lara): Hitler’s youngest personal secretary, 1942-1945. Released an autobiography in 2002 and appeared in the documentary Im toten Winkel / Blind Spot, also in 2002. She died in Munich that same year. Eva Braun (played by Juliane Köhler): Hitler’s girlfriend and, very briefly, his wife. Committed suicide together with Hitler in April 1945. Hermann Fegelein (played by Thomas Kretschmann): Obergruppenführer or General in SS. Part of Hitler’s inner circle, due in part to marriage to Eva Braun’s sister and service as Himmler’s adjutant starting 1943. Fled bunker in April 1945 but was caught. Circumstances of death uncertain, but most likely executed in April 1945. Alfred Jodl (played by Christian Redl): A top officer in the Wehrmacht High Command. Signed the unconditional surrender in May 1945. Hanged October 1946 after Nuremberg Trial. Magda Goebbels (played by Corinna Harfouch): Joseph Goebbels’s wife. Had some role in the murder of their six children in Hitler’s bunker. Died May 1, 1945 along with Joseph Goebbels. Joseph Goebbels (played by Ulrich Matthes): Propaganda Minister, architect of Kristallnacht, directed book burnings. Died May 1, 1945 outside the bunker in an unconfirmed manner. Albert Speer (played by Heino Ferch): Hitler’s architect, also Minister of Armaments and War Production. Known as “the Nazi who said sorry.” At Nuremberg, sentenced to 20 years at Spandau. Released 1966, published two autobiographies. Died 1981 in London. Wilhelm Mohnke (played by André Hennicke): High-ranking General in the SS. -

Krebs, Tschacher, Speer Und Er

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Open Repository and Bibliography - Luxembourg THIS IS A POST-PRINT VERSION OF THE ARTICLE WHICH HAS NOW BEEN PUBLISHED CITATION: Krebs, S. & Tschacher, W. (2007). Speer und Er. Und Wir? Deutsche Geschichte in gebrochener Erinnerung. Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 58, 3, 163–173. Stefan Krebs/Werner Tschacher Speer und Er. Und Wir? Deutsche Geschichte in gebrochener Erinnerung Am 6. Oktober 1943 fand im Goldenen Saal des Posener Schlosses eine vom Sekretär des Führers und Leiter der Parteikanzlei Martin Bormann einberufene Tagung der Reichs- und Gauleiter statt. Bei der Zusammenkunft wurden diese von Führungspersönlichkeiten aus Militär und Wirtschaft, darunter der Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine Karl Dönitz, der Generalinspekteur der Luftwaffe Erhard Milch und der Reichsminister für Bewaffnung und Munition Albert Speer sowie sein enger Mitarbeiter, der Stahlindustrielle Walter Rohland, über die ernste militärische und wirtschaftliche Lage des „Dritten Reiches“ im fünften Kriegsjahr unterrichtet. 1 Am späten Nachmittag hielt dann auch Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler eine eineinhalbstündige Rede. In dieser setzte Himmler die Tagungsteilnehmer in brutaler Offenheit vom Völkermord an den europäischen Juden in Kenntnis. So führte er u.a. aus: „Der Satz »Die Juden müssen ausgerottet werden« mit seinen wenigen Worten, meine Herren, ist leicht ausgesprochen. Für den, der durchführen muß, was er fordert, ist es das Allerhärteste und Schwerste, was es gibt.“ Weiter teilte er mit: „Es trat an uns die Frage heran: Wie ist es mit den Frauen und Kindern? – Ich habe mich entschlossen, auch hier eine ganz klare Lösung zu finden. -

Joseph Goebbels 1 Joseph Goebbels

Joseph Goebbels 1 Joseph Goebbels Joseph Goebbels Reich propaganda minister Goebbels Chancellor of Germany In office 30 April 1945 – 1 May 1945 President Karl Dönitz Preceded by Adolf Hitler Succeeded by Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk (acting) Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda In office 13 March 1933 – 30 April 1945 Chancellor Adolf Hitler Preceded by Office created Succeeded by Werner Naumann Gauleiter of Berlin In office 9 November 1926 – 1 May 1945 Appointed by Adolf Hitler Preceded by Ernst Schlange Succeeded by None Reichsleiter In office 1933–1945 Appointed by Adolf Hitler Preceded by Office created Succeeded by None Personal details Born Paul Joseph Goebbels 29 October 1897 Rheydt, Prussia, Germany Joseph Goebbels 2 Died 1 May 1945 (aged 47) Berlin, Germany Political party National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) Spouse(s) Magda Ritschel Children 6 Alma mater University of Bonn University of Würzburg University of Freiburg University of Heidelberg Occupation Politician Cabinet Hitler Cabinet Signature [1] Paul Joseph Goebbels (German: [ˈɡœbəls] ( ); 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. As one of Adolf Hitler's closest associates and most devout followers, he was known for his zealous orations and deep and virulent antisemitism, which led him to support the extermination of the Jews and to be one of the mentors of the Final Solution. Goebbels earned a PhD from Heidelberg University in 1921, writing his doctoral thesis on 19th century literature of the romantic school; he then went on to work as a journalist and later a bank clerk and caller on the stock exchange. -

{PDF} Goebbels Kindle

GOEBBELS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter Longerich | 992 pages | 16 Jun 2016 | Vintage Publishing | 9780099523697 | English | London, United Kingdom Joseph Goebbels () | American Experience | Official Site | PBS There will come a day, when all the lies will collapse under their own weight, and truth will again triumph. It is the absolute right of the State to supervise the formation of public opinion. We enter parliament in order to supply ourselves, in the arsenal of democracy, with its own weapons. If democracy is so stupid as to give us free tickets and salaries for this bear's work, that is its affair. We do not come as friends, nor even as neutrals. We come as enemies. As the wolf bursts into the flock, so we come. It would not be impossible to prove with sufficient repetition and a psychological understanding of the people concerned that a square is in fact a circle. They are mere words, and words can be molded until they clothe ideas and disguise. We shall reach our goal, when we have the power to laugh as we destroy, as we smash, whatever was sacred to us as tradition, as education, and as human affection. The essence of propaganda consists in winning people over to an idea so sincerely, so vitally, that in the end they succumb to it utterly and can never escape from it. If you tell a lie long enough, it becomes the truth. The English follow the principle that when one lies, it should be a big lie, and one should stick to it. Whoever can conquer the street will one day conquer the state, for every form of power politics and any dictatorship-run state has its roots in the street.