Volume 2 | Spring 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

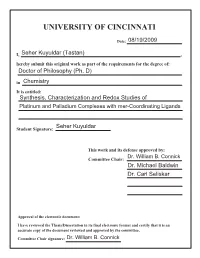

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 08/19/2009 I, Seher Kuyuldar (Tastan) , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D) in Chemistry It is entitled: Synthesis, Characterization and Redox Studies of Platinum and Palladium Complexes with mer-Coordinating Ligands Seher Kuyuldar Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Dr. William B. Connick Committee Chair: Dr. Michael Baldwin Dr. Carl Seliskar Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Dr. William B. Connick Synthesis, Characterization and Redox Studies of Platinum and Palladium Complexes with mer-Coordinating Ligands A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) In the Department of Chemistry of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Seher Kuyuldar (Tastan) B.S., Fatih University, 2002 Committee Chair: Dr. William B. Connick I Abstract Synthetic, structural, spectroscopic, and redox studies of platinum(II) and palladium(II) compounds with mer-coordinating ligands have been undertaken in an effort to better understand the role of the metal and the ligands in controlling d6/d8 electron-transfer reactions. A series of Pd(pip2NCN)X (pip2NCNH=1,3- bis(piperdylmethyl)benzene) and [Pd(pip2NNN)X]X (X=Cl, Br, I) (pip2NNN=2,6- bis(piperdyl-methyl)pyridine) complexes are reported. -

Tattoos & IP Norms

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 2013 Tattoos & IP Norms Aaron K. Perzanowski Case Western University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Repository Citation Perzanowski, Aaron K., "Tattoos & IP Norms" (2013). Faculty Publications. 47. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Article Tattoos & IP Norms Aaron Perzanowski† Introduction ............................................................................... 512 I. A History of Tattoos .............................................................. 516 A. The Origins of Tattooing ......................................... 516 B. Colonialism & Tattoos in the West ......................... 518 C. The Tattoo Renaissance .......................................... 521 II. Law, Norms & Tattoos ........................................................ 525 A. Formal Legal Protection for Tattoos ...................... 525 B. Client Autonomy ...................................................... 532 C. Reusing Custom Designs ......................................... 539 D. Copying Custom Designs ....................................... -

Synthesis and Characterizations of Novel Magnetic and Plasmonic Nanoparticles

SYNTHESIS AND CHARACTERIZATIONS OF NOVEL MAGNETIC AND PLASMONIC NANOPARTICLES by NAWEEN DAHAL B.S., TRIBHUVAN UNIVERSITY, 1995 M.S., TRIBHUVAN UNIVERSITY, 1997 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Abstract This dissertation reports the colloidal synthesis of iron silicide, hafnium oxide core-gold shell and water soluble iron-gold alloy for the first time. As the first part of the experimentation, plasmonic and superparamagnetic nanoparticles of gold and iron are synthesized in the form of core-shell and alloy. The purpose of making these nanoparticles is that the core-shell and alloy nanoparticles exhibit enhanced properties and new functionality due to close proximity of two functionally different components. The synthesis of core-shell and alloy nanoparticles is of special interest for possible application towards magnetic hyperthermia, catalysis and drug delivery. The iron-gold core-shell nanoparticles prepared in the reverse micelles reflux in high boiling point solvent (diphenyl ether) in presence of oleic acid and oleyl amine results in the formation of monodisperse core-shell nanoparticles. The second part of the experimentation includes the preparation of water soluble iron- gold alloy nanoparticles. The alloy nanoparticles are prepared for the first time at relatively low temperature (110 oC). The use of hydrophilic ligand 3-mercapto-1-propane sulphonic acid ensures the aqueous solubility of the alloy nanoparticles. Next, hafnium oxide core-gold shell nanoparticles are prepared for the first time using high temperature reduction method. These nanoparticles are potentially important as a high κ material in semiconductor industry. -

The Bush Revolution: the Remaking of America's Foreign Policy

The Bush Revolution: The Remaking of America’s Foreign Policy Ivo H. Daalder and James M. Lindsay The Brookings Institution April 2003 George W. Bush campaigned for the presidency on the promise of a “humble” foreign policy that would avoid his predecessor’s mistake in “overcommitting our military around the world.”1 During his first seven months as president he focused his attention primarily on domestic affairs. That all changed over the succeeding twenty months. The United States waged wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. U.S. troops went to Georgia, the Philippines, and Yemen to help those governments defeat terrorist groups operating on their soil. Rather than cheering American humility, people and governments around the world denounced American arrogance. Critics complained that the motto of the United States had become oderint dum metuant—Let them hate as long as they fear. September 11 explains why foreign policy became the consuming passion of Bush’s presidency. Once commercial jetliners plowed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, it is unimaginable that foreign policy wouldn’t have become the overriding priority of any American president. Still, the terrorist attacks by themselves don’t explain why Bush chose to respond as he did. Few Americans and even fewer foreigners thought in the fall of 2001 that attacks organized by Islamic extremists seeking to restore the caliphate would culminate in a war to overthrow the secular tyrant Saddam Hussein in Iraq. Yet the path from the smoking ruins in New York City and Northern Virginia to the battle of Baghdad was not the case of a White House cynically manipulating a historic catastrophe to carry out a pre-planned agenda. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Vibrational spectroscopy studies of interdiffusion in polymer laminates and diffusion of water into polymer membranes. HAJATDOOST, Sohail. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19741/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19741/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Sheffield Hallam University REFERENCE ONLY ProQuest Number: 10697043 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10697043 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Vibrational Spectroscopy Studies of Interdiffusion in Polymer Laminates and Diffusion of Water into Polymer Membranes by Sohail Hajatdoost A thesis submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 1996 ABSTRACT Confocal Raman microspectroscopy has been used to study the interdiffusion in polymer laminates at the interfacial region between the constituent polymer layers. -

The Drink Tank Sixth Annual Giant Sized [email protected]: James Bacon & Chris Garcia

The Drink Tank Sixth Annual Giant Sized Annual [email protected] Editors: James Bacon & Chris Garcia A Noise from the Wind Stephen Baxter had got me through the what he’ll be doing. I first heard of Stephen Baxter from Jay night. So, this is the least Giant Giant Sized Crasdan. It was a night like any other, sitting in I remember reading Ring that next Annual of The Drink Tank, but still, I love it! a room with a mostly naked former ballerina afternoon when I should have been at class. I Dedicated to Mr. Stephen Baxter. It won’t cover who was in the middle of what was probably finished it in less than 24 hours and it was such everything, but it’s a look at Baxter’s oevre and her fifth overdose in as many months. This was a blast. I wasn’t the big fan at that moment, the effect he’s had on his readers. I want to what we were dealing with on a daily basis back though I loved the novel. I had to reread it, thank Claire Brialey, M Crasdan, Jay Crasdan, then. SaBean had been at it again, and this time, and then grabbed a copy of Anti-Ice a couple Liam Proven, James Bacon, Rick and Elsa for it was up to me and Jay to clean up the mess. of days later. Perhaps difficult times made Ring everything! I had a blast with this one! Luckily, we were practiced by this point. Bottles into an excellent escape from the moment, and of water, damp washcloths, the 9 and the first something like a month later I got into it again, 1 dialed just in case things took a turn for the and then it hit. -

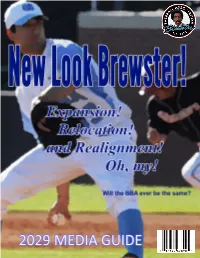

2029 BBA Media Guide

2029 MBBWA MEDIA GUIDE – Page 2 EST. 1973 – 2029, WE VOTE NONE OF THE ABOVE LEADERSHIP Commissioner: Matt Rectenwald Vice Commissioner & Reviewer Extraordinaire: Aaron Weiner League Director & Chief Muckraker: Kyle Stever PR Director/Historian: Stephen Lane LEAGUE AFFILIATES North America Brewster Baseball Association CONTACT INFORMATION Primary Website:: http://mbwba.whsites.net/ Forums: http://montybrewster.net/MBBA/phpBB3/index.php Commissioner Email: [email protected] OOTP Forum Entry: http://www.ootpdevelopments.com/board/ootp-17-online-leagues/267282-monty- brewster-world-baseball-association.html Here’s a clue: don’t try to tell any of us here in the BBA that our Out of the Park Baseball world is anything but the real thing. At the time of this writing, we follow the church of version 17. No more. No less. 17, got that? Feel free to check out the forums or our website. Listen to whatever is going to happen with the Drew Zodcast. Partake of our world class writing, all of it except the Genius’s stuff. You really can’t take any of that for gospel, though it might be worth a spit take or two. Actually, we’re thinking he’s not actually real but no one can match his mental acrobatics yet, so we’re really not sure. 2029 MBBWA MEDIA GUIDE – Page 3 CONTENTS Brewster Strikes Again! An Inside Look at How Expansion Went Down (Rectenwaldr) 2028 in the rearview mirror 2028 Final Standings (Collins) EBA, The Demise of a perfectly Good Baseball League (Palin/Riddler) FEATURES One Last Ride On the Expansion Rodeo (Schmidt) Welcome to the Projection -

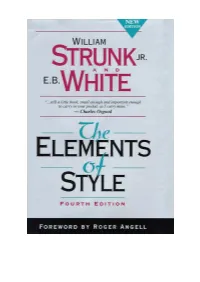

THE ELEMENTS of STYLE' (4Th Edition) First Published in 1935, Copyright © Oliver Strunk Last Revision: © William Strunk Jr

2 OLIVER STRUNK: 'THE ELEMENTS OF STYLE' (4th edition) First published in 1935, Copyright © Oliver Strunk Last Revision: © William Strunk Jr. and Edward A. Tenney, 2000 Earlier editions: © Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1959, 1972 Copyright © 2000, 1979, ALLYN & BACON, 'A Pearson Education Company' Introduction - © E. B. White, 1979 & 'The New Yorker Magazine', 1957 Foreword by Roger Angell, Afterward by Charles Osgood, Glossary prepared by Robert DiYanni ISBN 0-205-30902-X (paperback), ISBN 0-205-31342-6 (casebound). ________ Machine-readable version and checking: O. Dag E-mail: [email protected] URL: http://orwell.ru/library/others/style/ Last modified on April, 2003. 3 The Elements of Style Oliver Strunk Contents FOREWORD ix INTRODUCTION xiii I. ELEMENTARY RULES OF USAGE 1 1. Form the possessive singular of nouns by adding 's. 1 2. In a series of three or more terms with a single conjunction, use a comma after each term except the last. 2 3. Enclose parenthetic expressions between commas. 2 4. Place a comma before a conjunction introducing an independent clause. 5 5. Do not join independent clauses with a comma. 5 6. Do not break sentences in two. 7 7. Use a colon after an independent clause to introduce a list of particulars, an appositive, an amplification, or an illustrative quotation. 7 8. Use a dash to set off an abrupt break or interruption and to announce a long appositive or summary. 9 9. The number of the subject determines the number of the verb. 9 10. Use the proper case of pronoun. 11 11. A participial phrase at the beginning of a sentence must refer to the grammatical subject. -

Long-Lived Hot-Carrier Light Emission and Large Blue Shift in Formamidinium Tin Triiodide Perovskites

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-02684-w OPEN Long-lived hot-carrier light emission and large blue shift in formamidinium tin triiodide perovskites Hong-Hua Fang 1, Sampson Adjokatse1, Shuyan Shao1, Jacky Even 2 & Maria Antonietta Loi1 A long-lived hot carrier population is critical in order to develop working hot carrier photo- voltaic devices with efficiencies exceeding the Shockley–Queisser limit. Here, we report photoluminescence from hot-carriers with unexpectedly long lifetime (a few ns) in for- 1234567890():,; mamidinium tin triiodide. An unusual large blue shift of the time-integrated photo- luminescence with increasing excitation power (150 meV at 24 K and 75 meV at 293 K) is displayed. On the basis of the analysis of energy-resolved and time-resolved photo- luminescence, we posit that these phenomena are associated with slow hot carrier relaxation and state-filling of band edge states. These observations are both important for our under- standing of lead-free hybrid perovskites and for an eventual future development of efficient lead-free perovskite photovoltaics. 1 Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials, University of Groningen, Nijenborgh 4, 9747 AG Groningen The Netherlands. 2 Fonctions Optiques pour les Technologies de l’Information (FOTON), UMR 6082, CNRS, INSA Rennes, Universitéde Rennes 1, Rennes 35708, France. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.A.L. (email: [email protected]) NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2018) 9:243 | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-02684-w | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-02684-w – fi ybrid organic inorganic perovskites have attracted the methods section. -

Terra Australis 27 © 2008 ANU E Press

terra australis 27 © 2008 ANU E Press Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: McDonald, Josephine. Title: Dreamtime superhighway : an analysis of Sydney Basin rock art and prehistoric information exchange / Jo McDonald. ISBN: 9781921536168 (pbk.) 9781921536175 (pdf) Series: Terra Australis ; 27 Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Rock paintings--New South Wales--Sydney Basin. Petroglyphs--New South Wales--Sydney Basin. Visual communication in art--New South Wales--Sydney Basin. Art, Aboriginal Australian--New South Wales--Sydney Basin. Aboriginal Australians--New South Wales--Sydney Basin--Antiquities. Dewey Number: 709.011309944 Copyright of the text remains with the contributors/authors, 2006. This book is copyright in all countries subscribing to the Berne convention. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Series Editor: Sue O’Connor Typesetting and design: Silvano Jung Cover photograph by Jo McDonalnd Back cover map: Hollandia Nova. Thevenot 1663 by courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Reprinted with permission of the National Library of Australia. Terra Australis Editorial Board: Sue O’Connor, Jack Golson, Simon Haberle, Sally Brockwell, Geoffrey Clark Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. -

Displays of Medici Wealth and Authority: the Acts of the Apostles and Valois Fêtes Tapestry Cycles

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2019 Displays of Medici Wealth and Authority: The Acts of the Apostles and Valois Fêtes Tapestry Cycles Madison L. Clyburn University of Central Florida Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Clyburn, Madison L., "Displays of Medici Wealth and Authority: The Acts of the Apostles and Valois Fêtes Tapestry Cycles" (2019). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 523. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/523 DISPLAYS OF MEDICI WEALTH AND AUTHORITY: THE ACTS OF THE APOSTLES AND VALOIS FÊTES TAPESTRY CYCLES by MADISON LAYNE CLYBURN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Art History in the College of Arts & Humanities and in the Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2019 Thesis Chair: Margaret Ann Zaho, Ph.D. © 2019 Madison Layne Clyburn ii ABSTRACT The objective of my research is to explore Medici extravagance, power, and wealth through the multifaceted artistic form of tapestries vis-à-vis two particular tapestry cycles; the Acts of the Apostles and the Valois Fêtes. The cycles were commissioned by Pope Leo X (1475- 1521), the first Medici pope, and Catherine de’ Medici (1519-1589), queen, queen regent, and queen mother of France. -

CORRESPONDENCE/MEMORANDUM______State of Wisconsin

CORRESPONDENCE/MEMORANDUM________________State of Wisconsin Date: August 26, 2021 To: Users of the Traffic Engineering, Operations & Safety (TEOpS) Manual From: Bill McNary State Traffic Engineer Subject: AUGUST 2021 ISSUANCE Listed below and placed in the BTO Manuals Library website are changes and additions to the Traffic Engineering, Operations & Safety Manual. Please make your coworkers aware of the following changes and that they can be found at http://wisconsindot.gov/Pages/doing-bus/local- gov/traffic-ops/manuals-and-standards/trans.aspx. The Traffic Engineering, Operations and Safety Manual can be found at: http://wisconsindot.gov/Pages/doing-bus/local-gov/traffic-ops/manuals-and- standards/teops/default.aspx The following changes to the TEOpS Manual have been made: • 1-5-5 Table of Contents (UPDATED) • 2-4-43 Conventional Road Intersections (NEW) • 2-4-44 Conventional Roads on Approaches to Interchanges (UPDATED) Placed figures near references in narrative. • 2-4-51 Rustic Road Signs (UPDATED). Updated assembly codes and replaced Figure 1 with updated figure/codes. • 12-5-3 Intersection Conflict Warning System (NEW) • 12-5-4 Friction Surface Treatment (NEW) • 13-5 Traffic Regulations Speed Limits (UPDATED). All subjects were updated, 13-5-2 was created. o Pulled useful information from the Speed Management Guidelines into 13-5-1 and retired Speed Management Guidelines. o Improved the policy’s flow in hopes of making it more user friendly and understandable. o Created a speed study process flowchart to go along with the instructions for each step. o Added tabular comparison of data collection methods (from speed mgmt. guidelines) o Changed the way transitional speed zone limits were defined (instead of a set minimum limit, the length is based on the approach speeds) o Provided updated speed study examples and links to helpful templates and applications o 13-5-2 was created specifically for more information on speed limits for locals including how to determine outlying districts and semiurban districts both visually and written.