Innawonga and Bunjima People Native Title Application Wc96/61; Wad6096/98

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal Languages South of the Kimberley Region

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - 124 HANDBOOK OF WESTERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES SOUTH OF THE KIMBERLEY REGION Nicholas Thieberger Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Thieberger, N. Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley Region. C-124, viii + 416 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1993. DOI:10.15144/PL-C124.cover ©1993 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES c: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W.Bender KA. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics DavidBradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University University of Adelaide S.H. Elbert G.N. O'Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Franklin KL. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W.Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W.Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K T' sou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. Uhlenbeck Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Leiden L.A. -

A Grammatical Sketch of Ngarla: a Language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY master thesis The department for linguistics and philology spring term 2007 A grammatical sketch of Ngarla: A language of Western Australia Torbjörn Westerlund Supervisor: Anju Saxena Abstract In this thesis the basic grammatical structure of normal speech style of the Western Australian language Ngarla is described using example sentences taken from the Ngarla – English Dictionary (by Geytenbeek; unpublished). No previous description of the language exists, and since there are only five people who still speak it, it is of utmost importance that it is investigated and described. The analysis in this thesis has been made by Torbjörn Westerlund, and the focus lies on the morphology of the nominal word class. The preliminary results show that the language shares many grammatical traits with other Australian languages, e.g. the ergative/absolutive case marking pattern. The language also appears to have an extensive verbal inflectional system, and many verbalisers. 2 Abbreviations 0 zero marked morpheme 1 first person 1DU first person dual 1PL first person plural 1SG first person singular 2 second person 2DU second person dual 2PL second person plural 2SG second person singular 3 third person 3DU third person dual 3PL third person plural 3SG third person singular A the transitive subject ABL ablative ACC accusative ALL/ALL2 allative ASP aspect marker BUFF buffer morpheme C consonant CAUS causative COM comitative DAT dative DEM demonstrative DU dual EMPH emphatic marker ERG ergative EXCL exclusive, excluding addressee FACT factitive FUT future tense HORT hortative ImmPAST immediate past IMP imperative INCHO inchoative INCL inclusive, including addressee INSTR instrumental LOC locative NEG negation NMLISER nominaliser NOM nominative N.SUFF nominal class suffix OBSCRD obscured perception P the transitive object p.c. -

![AR Radcliffe-Brown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4080/ar-radcliffe-brown-684080.webp)

AR Radcliffe-Brown]

P129: The Personal Archives of Alfred Reginald RADCLIFFE-BROWN (1881- 1955), Professor of Anthropology 1926 – 1931 Contents Date Range: 1915-1951 Shelf Metre: 0.16 Accession: Series 2: Gift and deposit register p162 Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown was born on 17 January 1881 at Aston, Warwickshire, England, second son of Alfred Brown, manufacturer's clerk and his wife Hannah, nee Radcliffe. He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A. 1905, M. A. 1909), graduating with first class honours in the moral sciences tripos. He studied psychology under W. H. R. Rivers, who, with A. C. Haddon, led him towards social anthropology. Elected Anthony Wilkin student in ethnology in 1906 (and 1909), he spent two years in the field in the Andaman Islands. A fellow of Trinity (1908 - 1914), he lectured twice a week on ethnology at the London School of Economics and visited Paris where he met Emily Durkheim. At Cambridge on 19 April 1910 he married Winifred Marie Lyon; they were divorced in 1938. Radcliffe-Brown (then known as AR Brown) joined E. L. Grant Watson and Daisy Bates in an expedition to the North-West of Western Australia studying the remnants of Aboriginal tribes for some two years from 1910, but friction developed between Brown and Mrs. Bates. Brown published his research from that time in an article titled “Three Tribes of Western Australia”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 43, (Jan. - Jun., 1913), pp. 143-194. At the 1914 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Melbourne, Daisy Bates accused Brown of gross plagiarism. -

Identity, Learning & Strengths

Deadly IDENTITY, LEARNING & STRENGTHS STUDENT NAME The Family Action Centre CONTENTS SESSION 1 : GETTING STARTED SESSION 2 : IDENTITY SESSION 3 : CHOICES FOR LIFE SESSION 4 : STRENGTHS SESSION 5 : RESPECT & CONNECTIONS SESSION 6 : HEADS UP – MENTORING SESSION 7 : MOVING FORWARD INTRODUCTION DEADLY STREAMING Acknowledgements Identity, Learning & Strengths Deadly Streaming brings together Craig Hammond’s What’s the go with Deadly Streaming? © The Family Action Centre contributions across a heap of Indigenous Projects University of Newcastle NSW Australia 2017 like Who’s Ya Mob, Brothers Inside and Stayin’ on Deadly Streaming is about identity, learning and life choices. It’s a program to help you build Track. confidence and connections as a young Aboriginal person. The Family Action Centre’s Deadly Streaming Project is supported by the University of Newcastle’s Centre of Craig (Bourkie) Hammond has worked with The Deadly Streaming includes a bunch of info and exercises and cultural activities to help you find out Excellence for Equity in Higher Education (CEEHE) and Family Action Centre at the Uni of Newcastle for over more about yourself and your connections to mob (family). funded through the Australian Federal Government’s 15 years. Bourkie is a proud Wailwan man, known for Higher Education and Participation Program (HEPP). being fun and thoughtful and for his awareness and You can use Deadly Streaming as a guide to help you stand strong and proud and make good life skills as a leader. Bourkie is determined to make a The Family Action Centre (FAC) is a multidisciplinary Centre choices today – and for life attached to the School of Health Sciences in the Faculty of difference in the lives of young Aboriginal men and Health and Medicine. -

PUBLISHED AS Smith, Nicholas 2015. “Murtuka Yirraru: Automobility in Pilbara Song-Poems”

PRE-COPYEDITED VERSION — PUBLISHED AS Smith, Nicholas 2015. “Murtuka Yirraru: Automobility in Pilbara Song-Poems”. Anthropological Forum, 25(3): 221-242. Downloaded from http://www.anthropologicalforum.net COPYRIGHT All rights held by Smith, Nicholas. You need to get the author’s permission for uses other than teaching and personal research. Murtuka yirraru: Automobility in Pilbara Song Poem Nick Smith La Trobe University - Anthropology & Sociology, Bundoora, Victoria, Australia Abstract Arguably one of the most enduring icons of modernity is the automobile. The innumerable songs about motor vehicles are testimony to this status. This article examines Pilbara Aboriginal (marrngu) songs about the murtuka (motorcar). Focussing on a particular style of song known as yirraru to Ngarla people of the De Grey River area in Western Australia, I explore a range of questions concerning the impact of automobility on marrngu life-worlds. Is the ‘freedom of the road’ a value historically shared by marrngu and walypala? Or is the marrngu passion for automobility evinced in these yirraru simply an adaptation of pre- colonial values, beliefs and behaviours associated with mobility? This is not an ethnomusicology article; I treat yirraru as narratives, narratives that convey something about the relational in marrngu modes of orientation and engagement with the motor vehicle. Using archival and ethnographic data I argue that murtuka song-poems show that marrngu regarded motor vehicles as instrumental in their own efforts for autonomy in the decades in which these yirraru originate (1920–1960s). Ultimately I consider what the enthusiastic embrace of the murtuka by marrngu might say about the nature of socio-cultural difference, similarity, and marrngu and walypala boundedness in the Pilbara. -

WA Health Language Services Policy

WA Health Language Services Policy September 2011 Cultural Diversity Unit Public Health Division WA Health Language Services Policy Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Context .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Government policy obligations ................................................................................................... 2 2. Policy goals and aims .................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Scope......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Guiding principles ............................................................................................................................................. 6 5. Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 6 6. Provision of interpreting and translating services .................................................................... -

Looking West: a Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia

A Guide to Aboriginal Records in Western Australia The Records Taskforce of Western Australia ¨ ARTIST Jeanette Garlett Jeanette is a Nyungar Aboriginal woman. She was removed from her family at a young age and was in Mogumber Mission from 1956 to 1968, where she attended the Mogumber Mission School and Moora Junior High School. Jeanette later moved to Queensland and gained an Associate Diploma of Arts from the Townsville College of TAFE, majoring in screen printing batik. From 1991 to present day, Jeanette has had 10 major exhibitions and has been awarded four commissions Australia-wide. Jeanette was the recipient of the Dick Pascoe Memorial Shield. Bill Hayden was presented with one of her paintings on a Vice Regal tour of Queensland. In 1993 several of her paintings were sent to Iwaki in Japan (sister city of Townsville in Japan). A recent major commission was to create a mural for the City of Armadale (working with Elders and students from the community) to depict the life of Aboriginal Elders from 1950 to 1980. Jeanette is currently commissioned by the Mundaring Arts Centre to work with students from local schools to design and paint bus shelters — the established theme is the four seasons. Through her art, Jeanette assists Aboriginal women involved in domestic and traumatic situations, to express their feelings in order to commence their journey of healing. Jeanette currently lives in Northam with her family and is actively working as an artist and art therapist in that region. Jeanette also lectures at the O’Connor College of TAFE. Her dream is to have her work acknowledged and respected by her peers and the community. -

Rio Tinto Iron Ore

Rio Tinto Iron Ore Brockman Syncline 4 – Revised Proposal Assessment on Proponent Information Environmental Review Document Hamersley Iron Pty Limited 152 – 158 St Georges Terrace, Perth GPO Box A42, Perth, WA 6837 July 2014 RTIO-HSE-0209902 Disclaimer and Limitation This report has been prepared by Rio Tinto Iron Ore (Rio Tinto), on behalf of Hamersley Iron Pty Limited (Hamersley Iron), specifically for the Brockman Syncline 4 Iron Ore Project. Neither the report nor its contents may be referred to without the express approval of Rio Tinto, unless the report has been released for referral and assessment of proposals. Document Status Approved for Issue Rev Author Reviewer/s Date To Whom Date A ‐ D M. Palandri T. Souster/P. Royce 02/12/13 E ‐ F T. Souster Project Team 08/01/14 1 T. Souster OEPA 04/02/2014 2 T. Souster OEPA 21/02/2014 T. Souster/A. OEPA 11/07/2014 3‐4 T. Souster/P. Royce 11/07/14 Featherstone July 2014 ii Brockman Syncline 4 – Revised Proposal API Environmental Review RTIO‐HSE‐0209902 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PROPONENT DETAILS ................................................................................................................1 1.2 THE BROCKMAN SYNCLINE 4 PROJECT .....................................................................................1 2 PROPOSAL DESCRIPTION................................................................................................... 6 2.1 PROVISION -

Cultural Environment

APPENDIX 3 CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT Detailed anthropological studies of most Pilbara Aboriginal peoples are, by and large, absent from the vast body of literature about Aus- tralian Aboriginal peoples. Early reports (e.g. Clement 1903; Brown 1912; 1913; Yabaroo 1899), more contemporary and quite significant works (e.g. Brandenstein 1967; 1970a; 1970b; 1973; Tindale 1974) and recent Aborigi- nal remembrances (Guruma Elders Group et al. 2001; Juluwarlu Aboriginal Cooperation 2007; Olive 1997) supply key information that assists when portraying different aspects of the region’s Aboriginal peoples. Most recently, development associated with mining and exploration projects creates a need to consult Aboriginal Elders so as to mitigate impact on places of special significance. This has resulted in a considerable number of anthropolog- ical reports, although most are unavailable due to a range of restrictions, thereby constituting a body of literature commonly described as grey liter- ature. McDonald (2007) and Goode (2009), both of which are referenced in this study, are representative of this information resource. The following discussions draw on this material, as well as a scatter- ing of ethnographic observations. In using this information, we frame the following discussions around two purposes. First, we present most of what is publicly known about the Nyiyaparli. Second, we develop an 26 | CRAFTING COUNTRY idea or model about how their social systems and lifeways may have appeared immediately prior to the influx of Europeans during the early 19th century. NYIYAPARLI LAND AND PEOPLE COUNTRY Nyiyaparli lands (Figure 3.13) extend from the Fortescue Marsh area in the north- west to the Western Desert near Jigalong in the south- east. -

Submission No.78

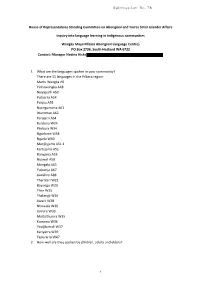

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Inquiry into language learning in Indigenous communities Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre} PO Box 2736, South Hedland WA 6722 Contact: Manager Nadine Hicks 1. What are the languages spoken in your community? There are 31 languages in the Pilbara region: Martu Wangka A6 Yinhawangka A48 Nyiyaparli A50 Putijarra A54 Palyku A55 Nyangumarta A61 Warnman A62 Karajarri A64 Burduna W24 Pinikura W34 Ngarluma W38 Ngarla W40 Manjilyjarra A51.1 Kartujarra A51 Banyjima A53 Nyamal A58 Mangala A65 Yulparija A67 Juwaliny A88 Tharrkari W21 Bayungu W23 Thiin W25 Thalanyji W26 Jiwarli W28 Nhuwala W30 Jurruru W33 Martuthunira W35 Kurrama W36 Yindjibarndi W37 Kariyarra W39 Yapurarra W47 2. How well are they spoken by children, adults and elders? 1 This varies widely. While some languages such as Thiin are no longer spoken at all, others such as Martu Wangka are widely spoken by all age groups. Detailed information for each language is available on request. 3. Describe your group and project? Wangka Maya was begun by a group of Pilbara language speakers who were concerned at the loss of languages. It aims to record and foster the Aboriginal languages of the Pilbara region. The group began with no funding working as volunteers. Gradually they attracted project funding and eventually ongoing funding as a language centre. a) Why was it important to start up? Almost no work was being done to record or foster the use of local languages. b) How long have you been running? Since 1987 c) What age group(s) are you working with? All ages. -

Pama-Nyungan), in Comparison with Two Neighbouring Languages

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 10: Special Issue on Humanities of the lesser-known: New directions in the description, documentation and typology of endangered languages and musics. Editors: Niclas Burenhult, Arthur Holmer, Anastasia Karlsson, Håkan Lundström & Jan-Olof Svantesson Main clause TAM-marking in Ngarla (Pama-Nyungan), in comparison with two neighbouring languages TORBJÖRN WESTERLUND Cite this article: Torbjörn Westerlund (2012). Main clause TAM-marking in Ngarla (Pama-Nyungan), in comparison with two neighbouring languages. In Niclas Burenhult, Arthur Holmer, Anastasia Karlsson, Håkan Lundström & Jan- Olof Svantesson (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 10: Special Issue on Humanities of the lesser-known: New directions in the description, documentation and typology of endangered languages and musics. London: SOAS. pp. 228-246 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/120 This electronic version first published: July 2014 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ -

Western Australia Skr Issuing Authority Based on Indigenous Peoples of Western Australia

WESTERN AUSTRALIA SKR ISSUING AUTHORITY BASED ON INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA CONSTRUCTIVE NOTICE TO THE GOVERNMENT OF AUSTRALIA 1. BE ADVISED that We, the Indigenous Tribal Peoples mentioned hereunder, as law-abiding Peoples, are invoking the Homestead principle and the Bill of Bracery (32 Hen. VIII, c.9) to stake lawful and legitimate claims upon all the gold and other precious metals present in the land and soil that we first occupied and owned for over 40,000 years prior to colonial settlements; 2. TAKE NOTICE that we did not invite European colonizers upon our land and soil. Europeans set foot upon our land and soil without valid visas and without our consent. They are yet to receive formal immigrant recognition from us as mentioned hereunder; 3. TAKE NOTICE that under customary international law and the disadvantages posed by Section 25 and Section 51(xxvi) of the Constitution of Australia, and despite the Act of Recognition of 13 February 2013 formally recognizing the Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, our land and resources’ rights were pre-ordained prior to uninvited colonization; 4. TAKE NOTICE that there are 66 operating gold mines in Australia including 14 of the world's largest, 11 of which are in Western Australian making it the country's major gold producer, accounting for almost 70 per cent of Australia's total gold production. 5. TAKE NOTICE that the six biggest gold mines are Boddington (two million ounces have been mined and extracted since 2012) Fimiston, Jundee, Telfer, and Sunrise Dam. 6. TAKE NOTICE that none of us mentioned hereunder received one penny of the wealth that has been mined off our lands.