Intelligence Cooperation in Belgium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of British Intelligence Assessment, 1940-41

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1999 The evolution of British intelligence assessment, 1940-41 Tang, Godfrey K. Tang, G. K. (1999). The evolution of British intelligence assessment, 1940-41 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/18755 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25336 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Evolution of British Intelligence Assessment, 1940-41 by Godfiey K. Tang A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FLTLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 1999 O Godfiey K Tang 1999 National Library Biblioth4que nationale #*lof Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OnawaON K1AON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant Pla National Library of Canada to Blbliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distciiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/f&n, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format Bectronique. -

Smith, Walter B. Papers.Pdf

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum Audiovisual Department Walter Bedell Smith: Papers 66-299--66-402-567; 68-459--68-464; 70-38; 70-45; 70-102--70-104; 70-185-1--70-185-48; 70-280-1--70-280-342 66-299-1 Color Guard at a convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. Copyright: unknown. One 5x7 B&W print. 66-299-2 A convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. L to R: Major General John A. Dabney, Commanding General, Fort Jackson; Lt. General A. R. Bolling, Commanding General, the 3rd Army; Captain W.L. Anderson, commanding officer of the Naval ROTC; General Smith, Colonel H.C. Mewshaw, commanding officer of the South Carolina Military District; University President Donald S. Russell; Brigadier General C.M. McQuarris, assistant post commander at Fort Jackson; Colonel Raymond F. Wisehart, commanding officer, Air Force ROTC; and Carter Burgess, assistant to the University president. Copyright: unknown. One 5x7 B&W print. 66-299-3 A convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. L to R: General Smith, Dr. Orin F. Crow, dean of the University faculty; University President Donald S. Russell; and Dr. L.E. Brubaker, Chaplain of the University. Copyright: unknown. One 5x7 B&W print. 66-299-4 A convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. -

Operation-Overlord.Pdf

A Guide To Historical Holdings In the Eisenhower Library Operation OVERLORD Compiled by Valoise Armstrong Page 4 INTRODUCTION This guide contains a listing of collections in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library relating to the planning and execution of Operation Overlord, including documents relating to the D-Day Invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. That monumental event has been commemorated frequently since the end of the war and material related to those anniversary observances is also represented in these collections and listed in this guide. The overview of the manuscript collections describes the relationship between the creators and Operation Overlord and lists the types of relevant documents found within those collections. This is followed by a detailed folder list of the manuscript collections, list of relevant oral history transcripts, a list of related audiovisual materials, and a selected bibliography of printed materials. DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY Abilene, Kansas 67410 September 2006 Table of Contents Section Page Overview of Collections…………………………………………….5 Detailed Folder Lists……………………………………………….12 Oral History Transcripts……………………………………………41 Audiovisual: Still Photographs…………………………………….42 Audiovisual: Audio Recordings……………………………………43 Audiovisual: Motion Picture Film………………………………….44 Select Bibliography of Print Materials…………………………….49 Page 5 OO Page 6 Overview of Collections BARKER, RAY W.: Papers, 1943-1945 In 1942 General George Marshall ordered General Ray Barker to London to work with the British planners on the cross-channel invasion. His papers include minutes of meetings, reports and other related documents. BULKELEY, JOHN D.: Papers, 1928-1984 John Bulkeley, a career naval officer, graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1933 and was serving in the Pacific at the start of World War II. -

Intelligence) Division, U.S

Processed by: TB BETTS Date: 5/4/93 BETTS, THOMAS J. (OH-397) 319 pages Open Officer in G-2 (intelligence) division, U.S. War Department, 1938-43; deputy G-2 at COSSAC and SHAEF, 1943-45 DESCRIPTION: Interview #1 [October 18, 1973; pp 1-84] Early life; travels abroad as a child. Early military career: decision to join army during World War I; commissioning of officers; coast artillery units; service in France; Camp Genicart near Bordeaux; Fort Eustis, VA, 1919-23; Philippines, 1923; Gen. Leonard Wood; service in China; return to US via Europe 1928; lack of promotions during inter-war years; Lyman Lemnitzer; coast artillery school, 1928-29. Ghostwriter in War Department, 1929-33: drafting speeches and reports for War Department, 1929-33: drafting speeches and reports for War Department officials; Patrick J. Hurley; DDE as a ghostwriter; Douglas MacArthur. Work with CCC in Illinois. G-2 (intelligence) officer at Presidio, San Francisco, 1935- 37: fear of communists and labor unions. Command & General Staff School, Fort Leavenworth, 1937-38. G-2 (intelligence) branch of War Department, 1938-43: organization of branch; Betts as a China expert; daily office routine; cooperation with State Department; Joseph Stilwell as military attaché in China; Japan-China War; deciphering Japanese diplomatic code (Purple); limited distribution of 1941; evaluation of State Department cable traffic; knowledge of German attack on Norway, 1940; Cordell Hull; lack of staff in G-2; importance of military attaché reports; Latin America; advance knowledge of Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Interview #2 [November 20, 1974; pp 85-129] G-2 (intelligence) branch of War Department: importance of State Department Cables; Col. -

Leaders Prep for Funding E≠Ort

Serving UNC students and the University community since 1893 Volume 120, Issue 17 dailytarheel.com Friday, March 23, 2012 Leaders MARCH AT THE ARCH prep for “We’re not going funding to get away from what we do. e≠ort Chancellor Holden Thorp and the We’re still going Board of Trustees began crafting a to play from the pitch for the next campaign. By Andy Thomason inside out.” University Editor Attempting to compensate for years of state funding cuts, University leaders now believe they Kendall Marshall, have at least one thing on their side — timing. UNC point guard With a two-year tuition plan set in stone and the NCAA investigation now in the past, Chancellor Holden Thorp and the Board of Trustees are looking to utilize the next 18 Though UNC’s strength is in the months to plan what they hope will be the University’s largest fundraising campaign ever. post, good 3-point shooting At Thursday’s meeting of the Board of Trustees, Thorp presented the vision behind could be the difference. the University’s coming campaign, along with marching orders for the board to adopt a more By Mark Thompson active role on campus as they try to hone an Senior Writer effective pitch. In the fall and early spring, administrators After a week-long search for the answer advocated for a two-year tuition plan with the of how to win without Kendall Marshall, intention of using the following 18-month quiet coach Roy Williams thinks he found the period to their advantage, Thorp said in an answer — and it might be simpler than he interview. -

D-Day: Planning Operation OVERLORD

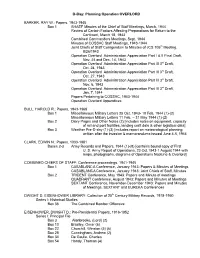

D-Day: Planning Operation OVERLORD BARKER, RAY W.: Papers, 1943-1945 Box 1 SHAEF Minutes of the Chief of Staff Meetings, March, 1944 Review of Certain Factors Affecting Preparations for Return to the Continent, March 18, 1943 Combined Commanders Meetings, Sept. 1944 Minutes of COSSAC Staff Meetings, 1943-1944 Joint Chiefs of Staff Corrigendum to Minutes of JCS 105th Meeting, 8/26/1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part I & II Final Draft, Nov. 24 and Dec. 14, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Oct. 24, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Oct. 27, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Nov. 6, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Jan. 7, 1944 Papers Pertaining to COSSAC, 1943-1944 Operation Overlord Appendices BULL, HAROLD R.: Papers, 1943-1968 Box 1 Miscellaneous Military Letters 25 Oct. 1943- 10 Feb. 1944 (1)-(2) Miscellaneous Military Letters 11 Feb. – 31 May 1944 (1)-(2) Box 2 Diary Pages and Other Notes (2) [includes notes on equipment, capacity of rail and port facilities, landing craft data & other logistical data] Box 3 Weather Pre-D-day (1)-(3) [includes report on meteorological planning written after the invasion & memorandums issued June 4-5, 1944 CLARK, EDWIN N.: Papers, 1933-1981 Boxes 2-3 Army Records and Papers, 1944 (1)-(8) [contains bound copy of First U. S. Army Report of Operations, 23 Oct.1943-1 August 1944 with maps, photographs, diagrams of Operations Neptune & Overlord] COMBINED CHIEFS OF STAFF: Conference proceedings, 1941-1945 Box 1 CASABLANC A Conference, January 1943: Papers & Minutes of Meetings CASABLANCA Conference, January 1943: Joint Chiefs of Staff, Minutes Box 2 TRIDENT Conference, May 1943: Papers and Minute of meetings QUADRANT Conference, August 1943: Papers and Minutes of Meetings SEXTANT Conference, November-December 1943: Papers and Minutes of Meetings, SEXTANT and EUREKA Conferences DWIGHT D. -

Montgomery and Eisenhower's British Officers

MONTGOMERY AND SHAEF Montgomery and Eisenhower’s British Officers MALCOLM PILL Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT When the British and American Governments established an Allied Expeditionary Force to liberate Nazi occupied Western Europe in the Second World War, General Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander and General Montgomery appointed to command British ground forces and, for the initial stages of the operation, all ground forces. Senior British Army officers, Lieutenant-General F. E. Morgan, formerly Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), and three officers from the Mediterranean theatre, Lieutenant-General K. Strong, Major-General H. Gale and Major-General J. Whiteley, served at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the aggressively hostile attitude of Montgomery towards the British officers, to analyse the reasons for it and to consider whether it was justified. The entry of the United States into the Second World War in December 1941 provided an opportunity for a joint command to undertake a very large and complex military operation, the invasion of Nazi occupied Western Europe. Britain would be the base for the operation and substantial British and American forces would be involved. At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt set up an integrated Allied planning staff with a view to preparing the invasion. In April 1943, Lieutenant-General Frederick Morgan was appointed Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC) for the operation, an appointment approved by Churchill following a lunch with Morgan at Chequers. Eight months later, in December 1943, General Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander and the staff at COSSAC, including Morgan, merged into Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). -

Sixteenth Episcopal District

AMEC General Conference 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL CONFERENCE AGENDA. .......................................................................................................................... 2 BISHOPS OF THE CHURCH 2016-2020................................................................................................................... 13 RETIRED BISHOPS. ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 WOMEN’S MISSIONARY SOCIETY SUPERVISORS 2016-2020. .................................................................... 18 GENERAL OFFICERS 2016-2020. ............................................................................................................................. 23 CONNECTIONAL DEPARTMENT HEADS AND OFFICERS 2016-2020 ...................................................... 26 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2016-2020. .......................................................................................................................... 30 JUDICIAL COUNCIL 2016-2020. ................................................................................................................................. 33 COLLEGE AND SEMINARY PRESIDENTS AND DEANS. ................................................................................... 34 ENDORSED AME CHAPLAINS. .................................................................................................................................... 37 GENERAL CONFERENCE COMMISSION. ................................................................................................................ -

An Examination of the Intelligence Preparation for Operation MARKET-GARDEN, September, 1944 Steven D

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1997 An Examination of the Intelligence Preparation for Operation MARKET-GARDEN, September, 1944 Steven D. Rosson Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Rosson, Steven D., "An Examination of the Intelligence Preparation for Operation MARKET-GARDEN, September, 1944" (1997). Masters Theses. 1824. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1824 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is rece1v1ng a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. 30 APR/99'7- Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author Date An Examination of the Intelligence Preparation For Operation MARKET-GARDEN, September, 1944 (TITLE) BY Captain Steven D. -

Eisenhower, Dwight D.: Post-Presidential Papers, 1961-69

EISENHOWER, DWIGHT D.: POST-PRESIDENTIAL PAPERS, 1961-69 1968 PRINCIPAL FILE Series Description The 1968 Principal File contains the main office files of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Gettysburg Office. The series is divided into three subseries. The first thirty-six boxes comprise a subject file arranged by categories, such as appointments, Eisenhower Center, foreign affairs, gifts, invitations, memberships, messages, political affairs, public relations, and trips. The alphabetical subseries occupies the next eleven boxes, and is arranged by the name of the individual or organization corresponding with Eisenhower. The final four boxes contain the “Bulk File” subseries, which has printed materials and oversized items. In 1968 Dwight Eisenhower suffered heart attacks in April and August, and he spent a number of months in the hospital, first at March Air Force Base in California and later at Walter Reed in Washington, D.C. His health problems greatly affected his ability to keep up his correspondence and limited the number of appointments he could keep. The series contains a large number of get-well letters and cards. Many requests for endorsements, special messages, autographs, gifts, and letters, as well as invitations to various events, were turned down by his office staff due to Eisenhower’s ill health and the limits placed on his activities by his doctors. Although Ike’s ability to travel and participate in many events was restricted by his growing health concerns, he continued to communicate with many prominent people on vital issues of the day. His correspondence frequently contains comments on U.S. foreign policy, particularly on Vietnam and the Middle East. -

FF 2018-1 Pages @ A4.Indd

OBITUARIES & APPRECIATIONS Kenneth Wunderlich It is with sadness that we inform members of the death of Kenneth Wunderlich, a two-time circumnavigator and OCC member for over 50 years, who passed away on 20 June 2017 in Revere, Massachusetts at the age of 84. He was proud of his membership and flew the flying fish burgee on all three of his boats. Although in his later years and no longer sailing, he still enjoyed reading about the passages made by other members, chronicled in the Newsletter and Flying Fish. Kenneth graduated from Columbia University, NY and became an electrical engineer. Working in Research and Development for American Science and Engineering he was involved in many projects, including the Hubble Telescope and airport Cat Scan security systems. Later he would work at GTE in the Boston area. He married Bebe, his wife and sailing partner of 58 years, in 1959. His interest in sailing didn’t start until his twenties, when he became friends with some serious sailors and was very influenced by a lecture given by two circumnavigators. While discussing the lecture with his cousin Patience Wales and her husband someone said ‘we could do that’, and the idea was born for the four of them to sail around the world together. The first boat that Kenneth and Bebe purchased was a 42ft wooden Atkins ketch which they named Kismet. They set off in her in 1963 on their first circumnavigation, via the Panama and Suez Canals, which they completed in 1967. It was during this circumnavigation that Kenneth completed his qualifying passage of 2900 miles from the Galapagos Islands to the Marquesas, and he joined the OCC in 1965. -

British Intelligence and the Anglo[Hyphen]American ‘

Review of International Studies (1998), 24, 331–351 Copyright © British International Studies Association British intelligence and the Anglo-American ‘Special Relationship’ during the Cold War* RICHARD J. ALDRICH Abstract. Our present understanding of British intelligence and its relationship to Anglo- American cooperation in the postwar period leaves much to be desired. Indeed while it has often been remarked that the twin pillars of Anglo-American security cooperation were atomic weapons and intelligence exchange, there remains an alarming disparity in our understanding of these two areas. The importance of intelligence is often commented on, but rarely subjected to sustained analysis. This article seeks to fill that gap by looking in turn at the nature of the Western ‘intelligence community’, the impact of alliance politics upon intelligence common to national estimates and the significance of strategic intelligence cooperation. Since 1945, rapid technological change has provided military forces with increased mobility and almost unlimited firepower. The ability of states to carry out surprise attacks has correspondingly increased; indeed, some analysts have gone so far as to suggest that surprise attacks will almost invariably meet with short-term success. Events in the South Atlantic in 1982 and in Kuwait in 1990 lend support to this hypothesis. A direct response to the related problems posed by rapid technological change and surprise attack has been the contemporaneous growth of intelligence communities. The central objective of these intelligence communities has been to offer precise estimates of the capabilities of opponents and timely warning of their intentions.1 From the outset, the British Chiefs of Staff (COS) were conscious of the con- nections between new strategic developments, the possibility of surprise attack and the growing importance of strategic intelligence.