King's Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Army Co-Operation Command and Tactical Air Power Development in Britain, 1940-1943: the Role of Army Co-Operation Command in Army Air Support

ARMY CO-OPERATION COMMAND AND TACTICAL AIR POWER DEVELOPMENT IN BRITAIN, 1940-1943: THE ROLE OF ARMY CO-OPERATION COMMAND IN ARMY AIR SUPPORT By MATTHEW LEE POWELL A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2013 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the impact of the developments made during the First World War and the inter-war period in tactical air support. Further to this, it will analyse how these developments led to the creation of Army Co-operation Command and affected the role it played developing army air support in Britain. Army Co-operation Command has been neglected in the literature on the Royal Air Force during the Second World War and this thesis addresses this neglect by adding to the extant knowledge on the development of tactical air support and fills a larger gap that exists in the literature on Royal Air Force Commands. Army Co-operation Command was created at the behest of the army in the wake of the Battle of France. -

British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 William Styles Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge September 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy William Styles British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 This thesis is concerned with an analysis of British governmental attitudes and responses to communism in the United Kingdom during the early years of the Cold War, from the election of the Attlee government in July 1945 up until the election of the Wilson government in October 1964. Until recently the topic has been difficult to assess accurately, due to the scarcity of available original source material. However, as a result of multiple declassifications of both Cabinet Office and Security Service files over the past five years it is now possible to analyse the subject in greater depth and detail than had been previously feasible. The work is predominantly concerned with four key areas: firstly, why domestic communism continued to be viewed as a significant threat by successive governments – even despite both the ideology’s relatively limited popular support amongst the general public and Whitehall’s realisation that the Communist Party of Great Britain presented little by way of a direct challenge to British political stability. Secondly, how Whitehall’s understanding of the nature and severity of the threat posed by British communism developed between the late 1940s and early ‘60s, from a problem considered mainly of importance only to civil service security practices to one which directly impacted upon the conduct of educational policy and labour relations. -

The Evolution of British Intelligence Assessment, 1940-41

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1999 The evolution of British intelligence assessment, 1940-41 Tang, Godfrey K. Tang, G. K. (1999). The evolution of British intelligence assessment, 1940-41 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/18755 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/25336 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Evolution of British Intelligence Assessment, 1940-41 by Godfiey K. Tang A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FLTLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 1999 O Godfiey K Tang 1999 National Library Biblioth4que nationale #*lof Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OnawaON K1AON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant Pla National Library of Canada to Blbliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter, distciiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/f&n, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format Bectronique. -

Smith, Walter B. Papers.Pdf

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum Audiovisual Department Walter Bedell Smith: Papers 66-299--66-402-567; 68-459--68-464; 70-38; 70-45; 70-102--70-104; 70-185-1--70-185-48; 70-280-1--70-280-342 66-299-1 Color Guard at a convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. Copyright: unknown. One 5x7 B&W print. 66-299-2 A convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. L to R: Major General John A. Dabney, Commanding General, Fort Jackson; Lt. General A. R. Bolling, Commanding General, the 3rd Army; Captain W.L. Anderson, commanding officer of the Naval ROTC; General Smith, Colonel H.C. Mewshaw, commanding officer of the South Carolina Military District; University President Donald S. Russell; Brigadier General C.M. McQuarris, assistant post commander at Fort Jackson; Colonel Raymond F. Wisehart, commanding officer, Air Force ROTC; and Carter Burgess, assistant to the University president. Copyright: unknown. One 5x7 B&W print. 66-299-3 A convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. L to R: General Smith, Dr. Orin F. Crow, dean of the University faculty; University President Donald S. Russell; and Dr. L.E. Brubaker, Chaplain of the University. Copyright: unknown. One 5x7 B&W print. 66-299-4 A convocation in honor of Walter Bedell Smith at the University of South Carolina on October 20, 1953, in Columbia, South Carolina. -

Operation-Overlord.Pdf

A Guide To Historical Holdings In the Eisenhower Library Operation OVERLORD Compiled by Valoise Armstrong Page 4 INTRODUCTION This guide contains a listing of collections in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Library relating to the planning and execution of Operation Overlord, including documents relating to the D-Day Invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. That monumental event has been commemorated frequently since the end of the war and material related to those anniversary observances is also represented in these collections and listed in this guide. The overview of the manuscript collections describes the relationship between the creators and Operation Overlord and lists the types of relevant documents found within those collections. This is followed by a detailed folder list of the manuscript collections, list of relevant oral history transcripts, a list of related audiovisual materials, and a selected bibliography of printed materials. DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY Abilene, Kansas 67410 September 2006 Table of Contents Section Page Overview of Collections…………………………………………….5 Detailed Folder Lists……………………………………………….12 Oral History Transcripts……………………………………………41 Audiovisual: Still Photographs…………………………………….42 Audiovisual: Audio Recordings……………………………………43 Audiovisual: Motion Picture Film………………………………….44 Select Bibliography of Print Materials…………………………….49 Page 5 OO Page 6 Overview of Collections BARKER, RAY W.: Papers, 1943-1945 In 1942 General George Marshall ordered General Ray Barker to London to work with the British planners on the cross-channel invasion. His papers include minutes of meetings, reports and other related documents. BULKELEY, JOHN D.: Papers, 1928-1984 John Bulkeley, a career naval officer, graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1933 and was serving in the Pacific at the start of World War II. -

Intelligence) Division, U.S

Processed by: TB BETTS Date: 5/4/93 BETTS, THOMAS J. (OH-397) 319 pages Open Officer in G-2 (intelligence) division, U.S. War Department, 1938-43; deputy G-2 at COSSAC and SHAEF, 1943-45 DESCRIPTION: Interview #1 [October 18, 1973; pp 1-84] Early life; travels abroad as a child. Early military career: decision to join army during World War I; commissioning of officers; coast artillery units; service in France; Camp Genicart near Bordeaux; Fort Eustis, VA, 1919-23; Philippines, 1923; Gen. Leonard Wood; service in China; return to US via Europe 1928; lack of promotions during inter-war years; Lyman Lemnitzer; coast artillery school, 1928-29. Ghostwriter in War Department, 1929-33: drafting speeches and reports for War Department, 1929-33: drafting speeches and reports for War Department officials; Patrick J. Hurley; DDE as a ghostwriter; Douglas MacArthur. Work with CCC in Illinois. G-2 (intelligence) officer at Presidio, San Francisco, 1935- 37: fear of communists and labor unions. Command & General Staff School, Fort Leavenworth, 1937-38. G-2 (intelligence) branch of War Department, 1938-43: organization of branch; Betts as a China expert; daily office routine; cooperation with State Department; Joseph Stilwell as military attaché in China; Japan-China War; deciphering Japanese diplomatic code (Purple); limited distribution of 1941; evaluation of State Department cable traffic; knowledge of German attack on Norway, 1940; Cordell Hull; lack of staff in G-2; importance of military attaché reports; Latin America; advance knowledge of Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Interview #2 [November 20, 1974; pp 85-129] G-2 (intelligence) branch of War Department: importance of State Department Cables; Col. -

Leaders Prep for Funding E≠Ort

Serving UNC students and the University community since 1893 Volume 120, Issue 17 dailytarheel.com Friday, March 23, 2012 Leaders MARCH AT THE ARCH prep for “We’re not going funding to get away from what we do. e≠ort Chancellor Holden Thorp and the We’re still going Board of Trustees began crafting a to play from the pitch for the next campaign. By Andy Thomason inside out.” University Editor Attempting to compensate for years of state funding cuts, University leaders now believe they Kendall Marshall, have at least one thing on their side — timing. UNC point guard With a two-year tuition plan set in stone and the NCAA investigation now in the past, Chancellor Holden Thorp and the Board of Trustees are looking to utilize the next 18 Though UNC’s strength is in the months to plan what they hope will be the University’s largest fundraising campaign ever. post, good 3-point shooting At Thursday’s meeting of the Board of Trustees, Thorp presented the vision behind could be the difference. the University’s coming campaign, along with marching orders for the board to adopt a more By Mark Thompson active role on campus as they try to hone an Senior Writer effective pitch. In the fall and early spring, administrators After a week-long search for the answer advocated for a two-year tuition plan with the of how to win without Kendall Marshall, intention of using the following 18-month quiet coach Roy Williams thinks he found the period to their advantage, Thorp said in an answer — and it might be simpler than he interview. -

La Guerre Aerienne Isolement Prolonge Sur Le Theatre D'operations

230 2 ° Partie : La guerre aerienne isolement prolonge sur le theatre d'operations de la Mediterranee, !'application et la poursuite de la politique de canadianisation prirent un ton particulier pour le 417e. Les remplacements, en particulier, sous la forme de pilotes experimentes pour servir de commandants et de seconds d'escadrilles, furent parfois difficiles a obtenir. Paradoxalement, a d'autres periodes, le probleme etait inverse, alors que les officiers d'etat-major devaient traiter le cas de Canadiens surqualifies pour lesquels il n 'existait aucune possibilite de promotion sur les theatres d'ope rations, a mains de les affecter a des escadrons OU des formations de la RAF. Un commandant d'escadrille experimente du 401e, par exemple, pouvait assez facilement etre promu au commandement d 'un autre escadron de chasse de I' ARC au Royaume-Uni, mais son alter ego du 417e n'avait qu 'une seule possibilite s'il voulait rester dans une unite de l 'ARC : ii devait attendre que son propre comman dant d'escadron soit affecte ailleurs ou soit abattu. Le 417e etait encore en Angleterre et s'exen;ait pour atteindre Jes normes operationnelles quand, a la mi-fevrier 1942, la Luftwaffe se joignit a la Kriegsmarine (marine allemande) pour realiser la« percee de la Manche »des croiseurs Scharnhorst et Gneisenau et du cuirassier lourd Prinz Eugen, a partir du port de Brest, de l 'Atlantique vers la Mer du Nord. L'echec de la RAF areagir rapidement et de maniere adequate, en depit de !'existence d'un plan de crise detaille pour !'operation Fuller, signifiait une occasion perdue pour Bentley Priory, qui doit accepter une part importante du blame. -

D-Day: Planning Operation OVERLORD

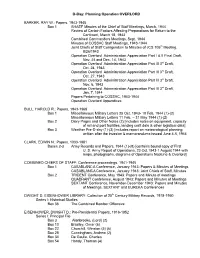

D-Day: Planning Operation OVERLORD BARKER, RAY W.: Papers, 1943-1945 Box 1 SHAEF Minutes of the Chief of Staff Meetings, March, 1944 Review of Certain Factors Affecting Preparations for Return to the Continent, March 18, 1943 Combined Commanders Meetings, Sept. 1944 Minutes of COSSAC Staff Meetings, 1943-1944 Joint Chiefs of Staff Corrigendum to Minutes of JCS 105th Meeting, 8/26/1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part I & II Final Draft, Nov. 24 and Dec. 14, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Oct. 24, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Oct. 27, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Nov. 6, 1943 Operation Overlord Administration Appreciation Part III 3rd Draft, Jan. 7, 1944 Papers Pertaining to COSSAC, 1943-1944 Operation Overlord Appendices BULL, HAROLD R.: Papers, 1943-1968 Box 1 Miscellaneous Military Letters 25 Oct. 1943- 10 Feb. 1944 (1)-(2) Miscellaneous Military Letters 11 Feb. – 31 May 1944 (1)-(2) Box 2 Diary Pages and Other Notes (2) [includes notes on equipment, capacity of rail and port facilities, landing craft data & other logistical data] Box 3 Weather Pre-D-day (1)-(3) [includes report on meteorological planning written after the invasion & memorandums issued June 4-5, 1944 CLARK, EDWIN N.: Papers, 1933-1981 Boxes 2-3 Army Records and Papers, 1944 (1)-(8) [contains bound copy of First U. S. Army Report of Operations, 23 Oct.1943-1 August 1944 with maps, photographs, diagrams of Operations Neptune & Overlord] COMBINED CHIEFS OF STAFF: Conference proceedings, 1941-1945 Box 1 CASABLANC A Conference, January 1943: Papers & Minutes of Meetings CASABLANCA Conference, January 1943: Joint Chiefs of Staff, Minutes Box 2 TRIDENT Conference, May 1943: Papers and Minute of meetings QUADRANT Conference, August 1943: Papers and Minutes of Meetings SEXTANT Conference, November-December 1943: Papers and Minutes of Meetings, SEXTANT and EUREKA Conferences DWIGHT D. -

Montgomery and Eisenhower's British Officers

MONTGOMERY AND SHAEF Montgomery and Eisenhower’s British Officers MALCOLM PILL Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT When the British and American Governments established an Allied Expeditionary Force to liberate Nazi occupied Western Europe in the Second World War, General Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander and General Montgomery appointed to command British ground forces and, for the initial stages of the operation, all ground forces. Senior British Army officers, Lieutenant-General F. E. Morgan, formerly Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), and three officers from the Mediterranean theatre, Lieutenant-General K. Strong, Major-General H. Gale and Major-General J. Whiteley, served at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the aggressively hostile attitude of Montgomery towards the British officers, to analyse the reasons for it and to consider whether it was justified. The entry of the United States into the Second World War in December 1941 provided an opportunity for a joint command to undertake a very large and complex military operation, the invasion of Nazi occupied Western Europe. Britain would be the base for the operation and substantial British and American forces would be involved. At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt set up an integrated Allied planning staff with a view to preparing the invasion. In April 1943, Lieutenant-General Frederick Morgan was appointed Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC) for the operation, an appointment approved by Churchill following a lunch with Morgan at Chequers. Eight months later, in December 1943, General Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander and the staff at COSSAC, including Morgan, merged into Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). -

Trenchard's Doctrine: Organisational Culture, the 'Air Force Spirit' and The

TRENCHARD’S DOCTRINE Trenchard’s Doctrine: Organisational Culture, the ‘Air Force spirit’ and the Foundation of the Royal Air Force in the Interwar Years ROSS MAHONEY Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT While the Royal Air Force was born in war, it was created in peace. In his 1919 memorandum on the Permanent Organization of the Royal Air Force, Air Marshal Sir Hugh Trenchard outlined his vision for the development of the Service. In this strategy, Trenchard developed the idea of generating an ‘Air Force spirit’ that provided the basis of the RAF’s development in the years after the First World War. The basis for this process was the creation of specific institutions and structures that helped generate a culture that allowed the RAF to establish itself as it dealt with challenges from its sister services. This article explores the character of that culture and ethos and in analysing the early years of the RAF through a cultural lens, suggests that Trenchard’s so-called ‘doctrine’ was focussed more on organisational developments rather than air power thinking as has often been suggested. In 1917, during the First World War and in direct response to the challenge of the aerial bombing of Great Britain, the British government decided to create an independent air service to manage the requirements of aerial warfare. With the formation of the Royal Air Force (RAF) on 1 April 1918, the Service’s senior leaders had to deal with the challenge of developing a new culture for the organisation that was consistent with the aims of the Air Force and delivered a sense of identity to its personnel. -

Sixteenth Episcopal District

AMEC General Conference 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL CONFERENCE AGENDA. .......................................................................................................................... 2 BISHOPS OF THE CHURCH 2016-2020................................................................................................................... 13 RETIRED BISHOPS. ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 WOMEN’S MISSIONARY SOCIETY SUPERVISORS 2016-2020. .................................................................... 18 GENERAL OFFICERS 2016-2020. ............................................................................................................................. 23 CONNECTIONAL DEPARTMENT HEADS AND OFFICERS 2016-2020 ...................................................... 26 BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2016-2020. .......................................................................................................................... 30 JUDICIAL COUNCIL 2016-2020. ................................................................................................................................. 33 COLLEGE AND SEMINARY PRESIDENTS AND DEANS. ................................................................................... 34 ENDORSED AME CHAPLAINS. .................................................................................................................................... 37 GENERAL CONFERENCE COMMISSION. ................................................................................................................