Nicholas Falcone, the Band Director You've Probably Never Heard of By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Edition

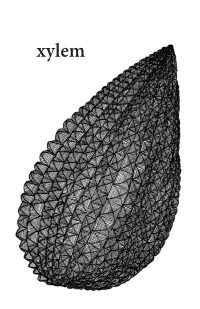

xylem i xylem2018-2019 ii iii editorial board Xylem Literary Magazine is a publication of the Editor-in-Chief Undergraduate English Association at the University of Allison Chu Michigan. Advertising and PR Chair Camille Gazoul SPONSORS Arts at Michigan Editing Chair Undergraduate English Association Henry Milek Events Chair Simran Malik Finance Chair Manasvini Rao Layout and Design Chair Stephanie Sim PRINTED BY Submissions Chair University Lithoprinters Angela Chen COVER ARTIST Phoebe Danaher Staff Clare Godfryd Aviva Klein Roman Knapp Olivia Lesh Matt Lujan Juhui Oh Sarah Salman Rachel Schonbaum Maya Simonte Jill Stecker iv v Dear reader, Thank you for picking up this issue of Xylem Literary Magazine. Xylem Literary Magazine has been in operation since the 1990s, annually publishing and promoting student creative work on the campus of the University of Michigan. The magazine is created, curated, and published annually by undergraduates, forming a unique opportunity for student voices to be heard throughout the publication process. We are proud to be a part of the strong Xylem, n. Collective term for the cells, vessels, and fibres literary tradition of both the university and the Ann Arbor forming the harder portion of the fibrovascular tissue; the community, catering to and supporting the dedication, talent, wood, as a tissue of the plant-body. and creativity of our communities. —OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY This year’s resulting magazine is particularly exemplary of the voices we hope to promote. We received submissions ranging from Xylem is a literary arts magazine that annually publishes clerihews to excerpts of longer stories, image collages to pencil the original creative work of University of Michigan drawings. -

Department Historyrevised Copy

The Music Department of Wayne State University A History: 1994-2019 By Mary A. Wischusen, PhD To Wayne State University on its Sesquicentennial Year, To the Music Department on its Centennial Year, and To all WSU music faculty and students, past, present, and future. ii Contents Preface and Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………………...........v Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………………............................ix Dennis Tini, Chair: 1993-2005 …………………………………………………………………………….1 Faculty .…………………………………………………………………………..............................2 Staff ………………………………………………………………………………………………...7 Fundraising and Scholarships …………………………………………………................................7 Societies and Organizations ……………………………………………..........................................8 New Music Department Programs and Initiatives …………………………………………………9 Outreach and Recruitment Programs …………………………………………….……………….15 Collaborative Programs …………………………………………………………………………...18 Awards and Honors ……………………………………………………………………………….21 Other Noteworthy Concerts and Events …………………………………………………………..24 John Vander Weg, Chair: 2005-2013 ………………………………………………................................37 Faculty………………………………………………………………..............................................37 Staff …………………………………………………………………………………………….....39 Fundraising and Scholarships …………………………………………………..............................40 New Music Department Programs and Initiatives ……………………………………………..…41 Outreach and Recruitment Programs ……………………………………………………………..45 Collaborative Programs …………………………………………………………………………...47 Awards -

The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music from the Dean

WINTER 2012 The News Magazine of the University of Illinois School of Music From the Dean On behalf of the College of Fine and Applied Arts, I want to congratulate the School of Music on a year of outstanding accomplishments and to WINTER 2012 thank the School’s many alumni and friends who Published for alumni and friends of the School of Music at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. have supported its mission. The School of Music is a unit of the College of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and has been an accredited institutional member of the National While it teaches and interprets the music of the past, the School is committed Association of Schools of Music since 1933. to educating the next generation of artists and scholars; to preserving our artistic heritage; to pursuing knowledge through research, application, and service; and Karl Kramer, Director Joyce Griggs, Associate Director for Academic Affairs to creating artistic expression for the future. The success of its faculty, students, James Gortner, Assistant Director for Operations and Finance J. Michael Holmes, Enrollment Management Director and alumni in performance and scholarship is outstanding. David Allen, Outreach and Public Engagement Director Sally Takada Bernhardsson, Director of Development Ruth Stoltzfus, Coordinator, Music Events The last few years have witnessed uncertain state funding and, this past year, deep budget cuts. The challenges facing the School and College are real, but Tina Happ, Managing Editor Jean Kramer, Copy Editor so is our ability to chart our own course. The School of Music has resolved to Karen Marie Gallant, Student News Editor Contributing Writers: David Allen, Sally Takada Bernhardsson, move forward together, to disregard the things it can’t control, and to succeed Michael Cameron, Tina Happ, B. -

Linda Yeo Leonard Recordings and Critical Listening Masterclass

Linda Yeo Leonard Recordings and Critical Listening Masterclass “World class players do not just happen – their talents are forged in the dual furnaces of determination and diligence.” -Edward Kleinhammer, former bass trombonist of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1940-1985) Becoming the best player you can will take hard work and determination. But if you work to become 1%-3% better every week you play your horn, just think how much better you could be in 6 months . a year. Wow- that would be exciting! I can’t stress the importance of listening to great recordings- I picked up many things from my father playing trombone in my house growing up. Many of you probably don’t have a parent who plays an instrument professionally. That’s fine- there are many excellent recordings out there of great musicians playing your instruments. Trombone: A Gala Festival (the Canadian Staff band, with Alain Trudel, Canadian trombone virtuoso- the best and fastest “Blue Bells of Scotland” I’ve ever heard! Proclamation, Two of a Mind, The Essential Rochut, Cornerstone, Take 1, and the New England Brass Band recordings on my dad’s website: www.yeodoug.com. Bass trombone solos and trombone duets with brass band, solos, recordings of him playing when he was younger, and rocking brass band recordings with him conducting) A New At Home and Experiments in Music, by Norman Bolter, my dad’s co-worker- former 2nd trombonist in the BSO At the End of the Century- Joe Alessi, principal trombonist of the NY Philharmonic Fancy Free, by Blair Bollinger, bass trombonist in the Philadelphia Symphony Orchestra Trombones De Costa Rica- rocking trombone 4ets Bonetown with Michael Davis and Bill Reichenbach The Legacy of Emory Remington and the Eastman Trombone Choir Euphonium: World of the Euphonium 5 by Stephen Mead CDs by the Childs Brothers American Variations by Brian Bowman Leonard Falcone and His Baritone Volumes 1-4 (Euphonium CDs suggested by Mr. -

Congressional Record—Senate S7606

S7606 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE June 10, 2003 we have the strength and the inspira- anthropology course at Murray State PERIODIC REPORT ON THE NA- tion to never give up until we reach it. University and a gifted and talented TIONAL EMERGENCY WITH RE- I got to know Burke Marshall be- camp at Western Kentucky University. SPECT TO THE RISK OF NU- cause, in 1970, he moved to Connecticut It is my pleasure to honor such an ex- CLEAR PROLIFERATION CRE- and joined the faculty of Yale Law ceptional and altruistic young lady for ATED BY THE ACCUMULATION School, my alma mater, where he her extraordinary charitable contribu- OF WEAPONS-USABLE FISSILE served as deputy dean and professor. I tions to her community. I thank the MATERIAL IN THE TERRITORY unfortunately had already graduated, Senate for allowing me to laud her OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION— but I was lucky to befriend Professor praises. She is one of Kentucky’s fin- PM 37 Marshall around New Haven. He was a est.∑ The PRESIDING OFFICER laid be- warm, kind, decent man, who believed f fore the Senate the following message that the fight for justice was never- from the President of the United ending. TRIBUTE TO DR. HARRY BEGIAN States, together with an accompanying The dean of Yale’s Law School, Tony ∑ report; which was referred to the Com- Kronman, put it well. He said, ‘‘His Mr. LEVIN. Mr. President, today I have the honor of recognizing a great mittee on Banking, Housing, and goodness was so large that I half be- Urban Affairs: lieved and fully wished he would live musician and educator from my home forever. -

Press Release 61011

Blue Lake Press Announces Publication of Leonard Falcone Biography Solid Brass is the story of Leonard Falcone, whose journey to America from Italy through Ellis Island at age 16 led to one of the most unlikely and inspirational careers in the history of the American band movement. Universally recognized as the greatest euphonium virtuoso of the 20th century, Falcone was Director of Bands at Michigan State University for 40 years, and through his leadership, discipline and musicianship, helped to establish a national reputation for the MSU Department of Music and Spartan Marching Band. This beautifully illustrated 398 page book will be published in September. Rita Comstock’s insightful biography chronicles Falcone’s remarkable life, including his early years growing up in culturally rich Roseto Valfortore, Italy, his success as a silent movie theater musician, the music department challenges during the depression and war years, the two Rose Bowl trips via private rail car courtesy of Oldsmobile, performing with the Michigan State Band for four sitting United States presidents, and his special relationship with Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp, where he would spend his final summers conducting and working with young students. Through it all, Leonard Falcone’s greatest legacy was the example he set as a man of honesty and integrity, who valued his family, his adopted country, and the importance of striving for excellence. His sense of humor and humble approach to leadership inspired thousands of student musicians, many of whom have become renowned performers, teachers and band leaders in their own right. An alumnus of Falcone’s Michigan State Band, Rita Comstock offers a fascinating look at Falcone’s professional and personal life. -

The Michigan Review Page December 6, 2005 the Michigan Review the Campus Affairs Journal at the University of Michigan Volume XXIV, Number 6 December 6, 2005 MR

THE MICHIGAN REVIEW Page December 6, 2005 THE MICHIGAN REVIEW The Campus Affairs Journal at the University of Michigan Volume XXIV, Number 6 December 6, 2005 MR DPS: What have you done for me lately? Cover Story.......................Page 3 Ludacris Losses................Page 5 Ailing Auto Industry.......Page 11 Editorials..........................Page 4 Columns...........................Page 6 Lassiter Interview...........Page 12 www.michiganreview.com THE MICHIGAN REVIEW Page 2 Serpent’s Tooth December 6, 2005 ■ The Serpent’s Tooth THE MICHIGAN REVIEW way mESSAgE OF the week: lion reward to the next person who kid- The Campus Affairs Journal of A“Ford Field looks like my fraternity naps a young, white female. Fox News Jewish groups demanded an apology the University of Michigan house after a party: It reeks of booze and Anchor greta Van Sustren has indicated from Michael Jackson last month after vomit, and everybody’s pissed because we she will take matters into her own hands he allegedly referred to Jews as “leech- James David Dickson didn’t score.” if needed. es” on an answering machine message. Editor in Chief Michael, sleeping with little boys is one The montreal gazette reports that Andre Last month’s election results yielded vic- thing, but when you start making fun of Paul Teske Boisclair, a gay Quebec politician, recent- tories by 18-year-olds in Michigan and the Jews… ly saw his approval rating among voters Iowa, an inmate in a California jail elected Publisher jump 11 points after he admitted using to a school board, and Kwame Kilpatrick. A member of Canada’s Parliament wants cocaine while serving in the provincial Democracy quickly surrendered. -

ABA Past Presidents (1930-2000)

The American Bandmasters Association Past Presidents 1930-2000 by Victor William Zajec, 2000 (Chicago, IL, March 4, 1923 - Homewood, IL, January 26, 2005) Revised by Raoul F. Camus, ABA Historian, 2017 Past Presidents of the American Bandmasters Association by Victor Zajec, Honorary Life Member and ABA Historian, was published in 2000. It was as much a history of the organization as that of the past presidents, and contained prefaces by several ABA presidents—Bryce Taylor, Stanley F. Michalski, Jr., and Edward S. Lisk. Except for the biographies, most of this information is presently available on the ABA web site. The ABA Board of Directors decided against reprinting the book and chose to put the biographies of the past presidents on the website in chronological order Additional information provided by Vincent J. Novara, curator, Special Collections in Performing Arts, Michelle Smith Performing Arts Library, University of Maryland. The American Bandmasters Association PRESIDENTS Arranged alphabetically 51. Allen, Eugene W. 1988 52. Julian, W J 1989 13. Bachman, Harold B. 1950 53. Kelly, Mark S. 1990 10. Bainum, Glenn Cliffe 1947 6. King, Karl L. 1938 47. Begian, Harry 1984 24. Kraushaar, Otto J. 1961 31. Berdahl, James E. 1968 63. Lisk, Edward S. 2000 58. Bloomquist, Kenneth G. 1995 30. Loboda, Samuel R. 1967 46. Boundy, Martin 1983 50. Long, John M. 1987 54. Bourgeois, John R. 1991 36. Mahan, Jack H. 1973 17. Brendler, Charles 1954 56. McBeth, W. Francis 1993 11. Bronson, Howard C. 1948 29. McCall, Fred W. 1966 7. Buys, Peter 1939 41. McGinnis, Donald E. 1978 3. -

Annual Report 1968 U

sart~a~ sb~t~a~~r ANNUAL REPORT 1968 U. 80-t.Zil\ l.tU UlerSt-! Zl188. bleb'Lb81t ~btru~nst st-~rns~~t ST. JOHN'S ARMENIAN CHURCH OF GREATER DETROIT ANNUAL REPORT sartlill" Sb'l.b'-u.«t-Jtr 1968 U. Bn-t.Zill.t~U trltrS~! ZU88. bteb'Lb81- ~btrU~na~ s~~rna~~ ST. JOHN'S ARMENIAN CHURCH OF GREATER DETROIT 22001 Northwestern Highway Southfield, Michigan 4807 5 U.'ltru q,nrur .QtfVuU.rljtt~• U.(}U.Q ~WJbW Stp r ~wnWJU ~n, CL r qnp~u 4bnwg ~ng, CL wnw2'11np~bw np'}Lng 'llngw. t~pgp tnJU Sbwnu u.u ~ nL~nJ r ~bpwJ ubp: Qqnp~u ~bnwg ubpng nL~p~ wpw r ubq Stp. CL qqnp~u ~bnwg ubpng JW2nrJ.bw ubq: ciJw n ,P ~ 0 (I b L n(I~ L n J bL ~ n q l n J U I.J (I p n J • U.JcfU bL up2111 bL JWL pU1bw'l/u JWL pU1bup g, I.J.U'~'lJ: )luwuU'InL~pL'II ~op Bpun1.u, Sn1.p pu~ puwuU'In L ~pLu' Qpwppu funp(pl, be. fuoubt, b1. qnrabt, U.nw2r ~n JwubuwJu dwu. r ~wp funp(p~ng, r pwupg OL r qnp~ng' ¢p4bw qpu, CL n~npubw ~n wpwpw~n g, t~. pu~ pwquwut'l}u: ('Utru~ u c'Unr~u.t.,- l, U. 0 u. sn~ rvnusn~u.'U.,tr) 2 ANNUAL PARISH ASSEMBLY ST. JOHN'S ARMENIAN CHURCH OF GREATER DETROIT Southfield, Michigan Friday February 28, 1969 8:00P.M. ARMENIAN CULTURAL BUILDING 22001 Northwestern Highway, Southfield Michigan AGENDA 1. -

Concert Band and University Band

Ensemble Concert: 2021-05-03 -- Concert Band and University Band Audio Playlist Video Playlist Access to audio and video playlists restricted to current faculty, staff, and students. If you have questions, please contact the Rita Benton Music Library at [email protected]. Scroll to see Program PDF ENSEMBLE CONCERT Concert Band & University Band Saturday, May 3, 2021 at 7:30pm Voxman Music Building Concert Hall University Band Tyler Strickland, conductor JT Womack, conductor Joshua Neuenschwander, guest conductor PROGRAM Fanfare and Flourishes James Curnow (for a Festive Occasion) (1991/1995/2013) (b. 1943) JT Womack, conductor Made for you and me: Michael Daugherty Inspired by Woodie Guthrie (2020) (b. 1954) Joshua Neuenschwander, guest conductor Two British Folk Songs (1993/2019) Elliot Del Borgo (1938–2013) adpt. Robert Longfield JT Womack, conductor Moscow, 1941 (2006/2020) Brian Balmages (b. 1975) Tyler Strickland, conductor Into the Clouds! (2007/2016) Richard L. Saucedo (b. 1957) Tyler Strickland, conductor Valdres (1904) Johannes Hanssen (1874–1967) arr. James Curnow Joshua Neuenschwander, guest conductor Concert Band Eric W. Bush, conductor Joshua Neuenschwander, guest conductor JT Womack, guest conductor Tyler Strickland, guest conductor PROGRAM Vanishing Point (2020) Randall Standridge (b. 1976) Folk Song Suite (1924/2000) Ralph Vaughan Williams I. March, Seventeen Come Sunday (1872–1958) II. Intermezzo, My Bonny Boy arr. Ed Huckeby III. March, Folk Songs from Somerset Tyler Strickland, guest conductor Life Painting (2020) Aaron Perrine (b. 1979) Strange Humors (1998/2020) John Mackey (b. 1973) JT Womack, guest conductor Nick Miller, Djembe A Time to Dance (2006/2020) Julie Giroux (b. 1961) Joshua Neuenschwander, guest conductor Programs supported by the Elizabeth M. -

Leonard Falcone Enrolled Part-Time at Michigan's University School of Music, While Continuing to Play in Theaters

Leonard Solid Brass by Rita Griffin Comstock Biography Falcone Biography Leonard Vincent Falcone was born April 5, 1899 in Roseto Valfortore, a Province of Foggia in Italy, one of Dominico and Maria Filippa (Finelli) Falcone's seven children. Leonard began his musical career in 1908 at the age of nine by playing the alto horn in the prestigious town band (known as the Roseto Valfortore Band or the "Banda Municipale") directed by the famous Donato Donatelli, Neapolitan Bandmaster. Leonard's brother, Nicholas, was also a member of the band. Nicholas emigrated to the United States in 1912 in order to pursue a career in music. In 1915, at the advent of World War I, Leonard joined him. Nicholas had found work in Ann Arbor as a tailor and clarinet player in a theater. Upon arriving in Michigan, Leonard became a tailor's assistant, and as a trombonist in a silent movie theater band in Ypsilanti that his brother was conducting. In 1917 Leonard Falcone enrolled part-time at Michigan's University School of Music, while continuing to play in theaters. Falcone was granted citizenship in 1924, and in 1926 graduated with a diploma in the violin. During this time, Nicholas had been appointed director of the Varsity Band at the University of Michigan. The Falcone brothers began to develop a sound reputation as musicians and conductors in the Ann Arbor community. The Secretary of Michigan State College contacted the Treasurer of the University of Michigan, and requested his recommendation for the position of Director of Bands at Michigan State. Both brothers were seriously considered for the position, but since Nicholas was settled with a wife and child in Ann Arbor, it was decided that Leonard, the bachelor, should take the position in East Lansing. -

THE MICHIGAN REVIEW the JOURNAL of CAMPUS AF FAIRS at the UNIVERSITY of MICHIGAN 03.08.07 VOLUME XXV, ISSUE 8 Features INSIDE THE

THE MICHIGAN REVIEW THE JOURNAL OF CAMPUS AF FAIRS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN 03.08.07 VOLUME XXV, ISSUE 8 Features INSIDE THE Professor and former Provost Paul Courant “SECRET SOCIETY” discusses economics A look inside Michigamua, the Order of Angell - and the progressive opposition of the University BY NICK CHEOLAS, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF But the society lives on, despite lawsuits, tion of the Michigan Union, Michigamua was documentaries, break-ins, expulsions, criticism granted a permanent lease in the Union tower P. 12 O SERVE MICHIGAN. and protests. And just as the society continues, in 1932. The organization remained in the tow- TThe aim of the senior society is simple. For so does the controversy. er until 2000. 105 years, the organization formerly known as All this in an organization that has, its Among its membership – which includes A look at the much- Michigamua – and now known as the Order of members contend, but one goal: to serve former President Gerald Ford and former maligned senior Angell – has fought to serve the University of Michigan. )RRWEDOO&RDFKDQG$WKOHWLF'LUHFWRUÀHOGLQJ society, the Order of Michigan above all else. Yost – the group also lists civil rights leader But the simplicity of their mission stands HISTORY and former Assistant Attorney General Roger Angell in sharp contrast to the controversy sparked by Founded in 1902 by a group of University Wilkins, a member of the Pride of 1953. the senior society. seniors in conjunction with University Presi- “Michigamua was integrated in the 1940s, P. 3 The group exists, its members say, to serve dent James Angell, early members adopted the up to two decades before many parts of cam- Michigan above all else.