System Klasyfikacji Organizmów

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fossils and Plant Phylogeny1

American Journal of Botany 91(10): 1683±1699. 2004. FOSSILS AND PLANT PHYLOGENY1 PETER R. CRANE,2,5 PATRICK HERENDEEN,3 AND ELSE MARIE FRIIS4 2Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, UK; 3Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, Washington DC 20052 USA; 4Department of Palaeobotany, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, S-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden Developing a detailed estimate of plant phylogeny is the key ®rst step toward a more sophisticated and particularized understanding of plant evolution. At many levels in the hierarchy of plant life, it will be impossible to develop an adequate understanding of plant phylogeny without taking into account the additional diversity provided by fossil plants. This is especially the case for relatively deep divergences among extant lineages that have a long evolutionary history and in which much of the relevant diversity has been lost by extinction. In such circumstances, attempts to integrate data and interpretations from extant and fossil plants stand the best chance of success. For this to be possible, what will be required is meticulous and thorough descriptions of fossil material, thoughtful and rigorous analysis of characters, and careful comparison of extant and fossil taxa, as a basis for determining their systematic relationships. Key words: angiosperms; fossils; paleobotany; phylogeny; spermatophytes; tracheophytes. Most biological processes, such as reproduction or growth distic context, neither fossils nor their stratigraphic position and development, can only be studied directly or manipulated have any special role in inferring phylogeny, and although experimentally using living organisms. Nevertheless, much of more complex models have been developed (see Fisher, 1994; what we have inferred about the large-scale processes of plant Huelsenbeck, 1994), these have not been widely adopted. -

S1. List of Taxa Included in the Disparity Analysis and the Phylogenetic Alysis, with Main References

S1. List of taxa included in the disparity analysis and the phylogenetic alysis, with main references. Taxa in bold are included in the phylogenetic analysis; taxa also indicated by * are included only in the phylogenetic analysis and not in the disparity analysis. Three unpublished arborescent taxa were included on the basis that they showed additional anatomical diversity. 1 Callixylon trunk from the Late Devonian of Marrocco showing large sclerotic nests in pith; 2 Axis from the late Tournaisian of Algeria, previously figured in Galtier (1988), and Galtier & Meyer-Berthaud (2006); 3 Trunk from the late Viséan of Australia. All these specimens and corresponding slides are currently kept in the Paleobotanical collections, Service des Collections, Université Montpellier II, France, under the specimen numbers 600/2/3, JC874 and YB1-2. Main reference Psilophyton* Banks et al., 1975 Aneurophytales Rellimia thomsonii Dannenhoffer & Bonamo, 2003; --- Dannenhoffer et al., 2007. Tetraxylopteris schmidtii Beck, 1957. Proteokalon petryi Scheckler & Banks, 1971. Triloboxylon arnoldii Stein & Beck, 1983. s m Archaeopteridales Callixylon brownii Hoskin & Cross, 1951. r e Callixylon erianum Arnold, 1930. p s o Callixylon huronensis Chitaley & Cai, 2001. n Callixylon newberry Arnold, 1931. m y g Callixylon trifilievii Lemoigne et al., 1983. o r Callixylon zalesskyi Arnold, 1930. P Callixylon sp. Meyer-Berthaud, unpublished data1. Eddya sullivanensis Beck, 1967. Protopityales Protopitys buchiana Scott, 1923; Galtier et al., 1998. P. scotica Walton, 1957. Protopitys sp. Decombeix et al., 2005. Elkinsiales Elkinsia polymorpha Serbet & Rothwell, 1992. Buteoxylales Buteoxylon gordonianum Barnard &Long, 1973; Matten et al., --- 1980. Triradioxylon primaevum Barnard & Long, 1975. Lyginopteridales Laceya hibernica May & Matten, 1983. Tristichia longii Galtier, 1977. -

SYSTÉMATIQUE DES EMBRYOPHYTES Document Illustrant Plus Particulièrement Les Taxons Européens Version 4 Octobre 2007

Université Pierre et Marie Curie (PARIS 6) Préparation à l’agrégation SVSTU, secteur B SYSTÉMATIQUE DES EMBRYOPHYTES Document illustrant plus particulièrement les taxons européens version 4 octobre 2007 Catherine Reeb, Préparation agrégation SVSTU, UPMC Jean-Yves Dubuisson, Laboratoire Paléobotanique et Paléoécologie, équipe Paléodiversité, systématique et évolution des Embryophytes, UPMC Dessin de couverture : extrait d’un traité botanique tibétain Pour Garance Remerciements: merci à Jean et Monique Duperon pour les clés de détermination des familles d’Angiospermes, à A.M pour la reproduction de couverture, à Michaël Manuel et Eric Queinnec pour la partie I de l’introduction. Egalement à tous les illustrateurs qui ont autorisé l’utilisation de leurs documents mis en ligne sur Internet : Françoise Gantet, Prof. I. Foissner, Association Endemia de Nouvelle Calédonie. 1 Table des matières Introduction 3 Les données essentielles pour l’agrégation . 5 I Systématique générale des Embryophytes 6 I.1 Caractères des Embryophytes . 6 I.2 La place des Embryophytes au sein de la lignée verte . 7 I.3 Le groupe frère des Embryophytes . 7 I.4 Relations au sein des Embryophytes :les points acquis aujourd’hui . 8 I.4.1 Marchantiophytes, Bryophytes, Anthocérotophytes à la base des Embryophytes . 8 I.4.2 Les Trachéophytes ou plantes vasculaires, un groupe monophylétique . 9 I.4.3 Les Spermatophytes ou plantes à ovules, un groupe monophylétique . 9 I.5 Quelques points encore en discussion . 11 I.5.1 Position et relations des trois clades basaux (Bryophytes, Marchantiophytes et Anthocérotophytes) 11 I.5.2 Relations au sein des Spermatophytes :l’hypothèse "Gnepine" . 13 II Les principaux clades d’Embryophytes 15 II.1 MARCHANTIOPHYTA:Les Marchantiophytes ou Hépatiques . -

Dr. Sahanaj Jamil Associate Professor of Botany M.L.S.M. College, Darbhanga

Subject BOTANY Paper No V Paper Code BOT521 Topic Taxonomy and Diversity of Seed Plant: Gymnosperms & Angiosperms Dr. Sahanaj Jamil Associate Professor of Botany M.L.S.M. College, Darbhanga BOTANY PG SEMESTER – II, PAPER –V BOT521: Taxonomy and Diversity of seed plants UNIT- I BOTANY PG SEMESTER – II, PAPER –V BOT521: Taxonomy and Diversity of seed plants Classification of Gymnosperms. # Robert Brown (1827) for the first time recognized Gymnosperm as a group distinct from angiosperm due to the presence of naked ovules. BENTHAM and HOOKSER (1862-1883) consider them equivalent to dicotyledons and monocotyledons and placed between these two groups of angiosperm. They recognized three classes of gymnosperm, Cyacadaceae, coniferac and gnetaceae. Later ENGLER (1889) created a group Gnikgoales to accommodate the genus giankgo. Van Tieghem (1898) treated Gymnosperm as one of the two subdivision of spermatophyte. To accommodate the fossil members three more classes- Pteridospermae, Cordaitales, and Bennettitales where created. Coulter and chamberlain (1919), Engler and Prantl (1926), Rendle (1926) and other considered Gymnosperm as a division of spermatophyta, Phanerogamia or Embryoptyta and they further divided them into seven orders: - i) Cycadofilicales ii) Cycadales iii) Bennettitales iv) Ginkgoales v) Coniferales vi) Corditales vii) Gnetales On the basis of wood structure steward (1919) divided Gymnosperm into two classes: - i) Manoxylic ii) Pycnoxylic The various classification of Gymnosperm proposed by various workers are as follows: - i) Sahni (1920): - He recognized two sub-divison in gymnosperm: - a) Phylospermae b) Stachyospermae BOTANY PG SEMESTER – II, PAPER –V BOT521: Taxonomy and Diversity of seed plants ii) Classification proposed by chamber lain (1934): - He divided Gymnosperm into two divisions: - a) Cycadophyta b) Coniterophyta iii) Classification proposed by Tippo (1942):- He considered Gymnosperm as a class of the sub- phylum pteropsida and divided them into two sub classes:- a) Cycadophyta b) Coniferophyta iv) D. -

Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation

i1 Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation William A. DiMichele, William E. Stein, and Richard M. Bateman DiMichele, W.A., Stein, W.E., and Bateman, R.M. 2001. Ecological sorting of vascular plant classes during the Paleozoic evolutionary radiation. In: W.D. Allmon and D.J. Bottjer, eds. Evolutionary Paleoecology: The Ecological Context of Macroevolutionary Change. Columbia University Press, New York. pp. 285-335 THE DISTINCTIVE BODY PLANS of vascular plants (lycopsids, ferns, sphenopsids, seed plants), corresponding roughly to traditional Linnean classes, originated in a radiation that began in the late Middle Devonian and ended in the Early Carboniferous. This relatively brief radiation followed a long period in the Silurian and Early Devonian during wrhich morphological complexity accrued slowly and preceded evolutionary diversifications con- fined within major body-plan themes during the Carboniferous. During the Middle Devonian-Early Carboniferous morphological radiation, the major class-level clades also became differentiated ecologically: Lycopsids were cen- tered in wetlands, seed plants in terra firma environments, sphenopsids in aggradational habitats, and ferns in disturbed environments. The strong con- gruence of phylogenetic pattern, morphological differentiation, and clade- level ecological distributions characterizes plant ecological and evolutionary dynamics throughout much of the late Paleozoic. In this study, we explore the phylogenetic relationships and realized ecomorphospace of reconstructed whole plants (or composite whole plants), representing each of the major body-plan clades, and examine the degree of overlap of these patterns with each other and with patterns of environmental distribution. We conclude that 285 286 EVOLUTIONARY PALEOECOLOGY ecological incumbency was a major factor circumscribing and channeling the course of early diversification events: events that profoundly affected the structure and composition of modern plant communities. -

Fundamentals of Palaeobotany Fundamentals of Palaeobotany

Fundamentals of Palaeobotany Fundamentals of Palaeobotany cuGU .叮 v FimditLU'φL-EjAA ρummmm 吋 eαymGfr 伊拉ddd仇側向iep M d、 況 O C O W Illustrations by the author uc削 ∞叩N Nn凹創 刊,叫MH h 咀 可 白 a aEE-- EEA First published in 1987 by Chapman αndHallLtd 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Published in the USA by Chα~pman and H all 29 West 35th Street: New Yo地 NY 10001 。 1987 S. V. M秒len Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1987 ISBN-13: 978-94-010-7916-7 e-ISBN-13: 978-94-009-3151-0 DO1: 10.1007/978-94-009-3151-0 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted, or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Mey凹, Sergei V. Fundamentals of palaeobotany. 1. Palaeobotany I. Title 11. Osnovy paleobotaniki. English 561 QE905 Library 01 Congress Catα loging in Publication Data Mey凹, Sergei Viktorovich. Fundamentals of palaeobotany. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Paleobotany. I. Title. QE904.AIM45 561 8ι13000 Contents Foreword page xi Introduction xvii Acknowledgements xx Abbreviations xxi 1. Preservation 抄'pes αnd techniques of study of fossil plants 1 2. Principles of typology and of nomenclature of fossil plants 5 Parataxa and eutaxa S Taxa and characters 8 Peculiarity of the taxonomy and nomenclature of fossil plants 11 The binary (dual) system of fossil plants 12 The reasons for the inflation of generic na,mes 13 The species problem in palaeobotany lS The polytypic concept of the species 17 Assemblage-genera and assemblage-species 17 The cladistic methods 18 3. -

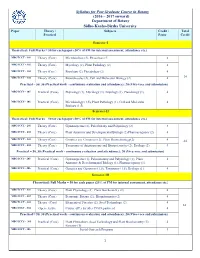

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 Onward)

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 onward) Department of Botany Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University Paper Theory / Subjects Credit / Total Practical Paper Credit Semester-I Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 101 Theory (Core) Microbiology (2), Phycology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 102 Theory (Core) Mycology (2), Plant Pathology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 103 Theory (Core) Bryology (2), Pteridology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 104 Theory (Core) Biomolecules (2), Cell and Molecular Biology (2) 4 24 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 105 Practical (Core) Phycology (1), Mycology (1), Bryology (1), Pteridology (1). 4 MBOTCCS - 106 Practical (Core) Microbiology (1.5), Plant Pathology (1), Cell and Molecular 4 Biology (1.5). Semester-II Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 201 Theory (Core) Gymnosperms (2), Paleobotany and Palynology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 202 Theory (Core) Plant Anatomy and Developmental Biology (2) Pharmacognosy (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 203 Theory (Core) Genetics and Genomics (2), Plant Biotechnology(2) 4 24 MBOTCCT - 204 Theory (Core) Taxonomy of Angiosperms and Biosystematics (2), Ecology (2) 4 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 205 Practical (Core) Gymnosperms (1), Palaeobotany and Palynology (1), Plant 4 Anatomy & Developmental Biology (1), Pharmacognosy (1). MBOTCCS - 206 Practical (Core) Genetics and Genomics (1.5), Taxonomy (1.5), Ecology (1). 4 Semester-III Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 301 Theory (Core) Plant Physiology (2), Plant Biochemistry (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 302 Theory (Core) Economic Botany (2), Bioinformatics (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 303 Theory (Core) Elements of Forestry (2), Seed Technology (2). -

Syllabus M.Sc. Botany (Choice Based Credit System)

Syllabus M.Sc. Botany (Choice Based Credit System) (To be implemented from the Academic Year 2017-18) DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY UNIVERSITY OF ALLAHABAD Page 1 of 21 DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY UNIVERSITY OF ALLAHABAD M.Sc. Syllabus (Choice Based Credit System) (To be implemented from the Academic Year 2017-18) Semester – I Course Code Marks Course Title Credits BOT501 100 Phycology and Limnology 3 BOT502 100 Mycology and Plant Pathology 3 BOT503 100 Bryology and Pteridology 3 BOT504 100 Gymnosperm and Palaeobotany 3 BOT531 100 Lab Work I (based on Course BOT501 and BOT502) 4 (Excursion/field work/ Project) BOT532 100 Lab Work II (based on Course BOT503 and BOT504) 4 (Excursion/field work/Project) Total credits 20 Semester – II Course Code Marks Course Title Credits BOT505 100 Plant Morphology and Anatomy 3 BOT506 100 Reproductive Biology, Morphogenesis and Tissue culture 3 BOT507 100 Taxonomy of Angiosperm and Economic Botany 3 BOT508 100 Ecology and Phytogeography 3 BOT533 100 Lab Work III (based on Course BOT505 and BOT506) 4 (Field work/ Project) BOT534 100 Lab Work IV (based on Course BOT507 and BOT508) 4 (Field work/ Project) Total credits 20 Semester – III Course Code Marks Course Title Credits BOT601 100 Plant Physiology 3 BOT602 100 Plant Biochemistry and Biochemical Techniques 3 BOT603 100 Cytogenetics, Plant Breeding and Biostatistics 3 BOT604 100 Microbiology 3 BOT631 100 Lab Work V (based on Course BOT601 and BOT602) 4 BOT632 100 Lab Work VI (based on Course BOT603 and BOT604) 4 Total credits 20 Semester – IV Course Code Marks Course -

A Reappraisal of Mississippian (Tournaisian and Visean) Adpression Floras from Central and Northwestern Europe

Zitteliana A 54 (2014) 39 A reappraisal of Mississippian (Tournaisian and Visean) adpression floras from central and northwestern Europe Maren Hübers1, Benjamin Bomfleur2*, Michael Krings3, Christian Pott2 & Hans Kerp1 1Forschungsstelle für Paläobotanik am Geologisch-Paläontologischen Institut, Westfälische Zitteliana A 54, 39 – 52 Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Heisenbergstraße 2, 48149 Münster, Germany München, 31.12.2014 2Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Paleobiology, Box 50007, SE-104 05, Stockholm, Sweden Manuscript received 3Department für Geo- und Umweltwissenschaften, Paläontologie und Geobiologie, Ludwig- 01.02.2014; revision Maximilians-Universität, and Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie, Richard- accepted 07.04.2014 Wagner-Straße 10, 80333 Munich, Germany ISSN 1612 - 412X *Author for correspondence and reprint requests: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Mississippian plant fossils are generally rare, and in central and northwestern Europe especially Tournaisian to middle Visean fossil floras are restricted to isolated occurrences. While sphenophytes and lycophytes generally are represented by only a few widespread and long-ranging taxa such as Archaeocalamites radiatus, Sphenophyllum tenerrimum and several species of Lepidodendropsis and Lepido- dendron, Visean floras in particular show a remarkably high diversity of fern-like foliage, including filiform types (Rhodea, Diplotmema), forms with bipartite fronds (Sphenopteridium, Diplopteridium, Spathulopteris, Archaeopteridium), others with monopodial, pinnate fronds (Anisopteris, Fryopsis) and still others characterized by several-times pinnate fronds (e.g., Adiantites, Triphyllopteris, Sphenopteris, Neu- ropteris). Most of these leaf types have been interpreted as belonging to early seed ferns, whereas true ferns seem to have been rare or lacking in impression/compression floras. In the upper Visean, two types of plant assemblages can be distinguished, i.e., the northern Kohlenkalk-type and the south-eastern Kulm-type assemblage. -

CPY Document

CHAPTER 1 Plant diversity has evolved and is evolving on the earth today according to the processes of natural selection. All basic "body plans" of vascular plants were in existence by the Early Carboniferous, approximately 340 million years ago, and each major radiation occupied a particular habitat type, for example, wetland versus terra firma, pristine versus disturbed environments. Today the great spe- cies diversity we see on theplanetis dominated by just a few of these hasicplant types. This chapter sets the stage to understanding the origin and radiation of plant diversity on the earth before the significant influence of humans. The im- plication is that plants may become more diverse in the number of species level over time, but less diverse in overall form. The history of life tells us that plants that are dominant and diverse today will certainly be inconspicuous or even ex--' tinct in the distant future. EVOLUTION OF LAND PLANT DIVERSITY MAJOR INNOVATIONS AND LINEAGES THROUGH TIME William A. DiMichele and Richard M. Bateman PLANT DIVERSITY VIEWED through the lens of deep time takes on a con- siderably different aspect than when examined in the present. Although the fossil record captures only fragments of the terrestrial world of the past 450 million years, it does indicate clearly that the world of today is simply a passing phase, the latest permutation in a string of spasmodic changes in the ecological organization of the terrestrial biosphere. The pace of change in species diversity and that of ecosystem structure and composition have followed broadly parallel paths, unquestionably related but not always changing in unison. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE ORCID ID: 0000-0003-0186-6546 Gar W. Rothwell Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor Emeritus Department of Environmental and Plant Biology Porter Hall 401E T: 740 593 1129 Ohio University F: 740 593 1130 Athens, OH 45701 E: [email protected] also Courtesy Professor Department of Botany and PlantPathology Oregon State University T: 541 737- 5252 Corvallis, OR 97331 E: [email protected] Education Ph.D.,1973 University of Alberta (Botany) M.S., 1969 University of Illinois, Chicago (Biology) B.A., 1966 Central Washington University (Biology) Academic Awards and Honors 2018 International Organisation of Palaeobotany lifetime Honorary Membership 2014 Fellow of the Paleontological Society 2009 Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society of America 2004 Ohio University Distinguished Professor 2002 Michael A. Cichan Award, Botanical Society of America 1999-2004 Ohio University Presidential Research Scholar in Biomedical and Life Sciences 1993 Edgar T. Wherry Award, Botanical Society of America 1991-1992 Outstanding Graduate Faculty Award, Ohio University 1982-1983 Chairman, Paleobotanical Section, Botanical Society of America 1972-1973 University of Alberta Dissertation Fellow 1971 Paleobotanical (Isabel Cookson) Award, Botanical Society of America Positions Held 2011-present Courtesy Professor of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University 2008-2009 Visiting Senior Researcher, University of Alberta 2004-present Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor of Environmental and Plant Biology, Ohio -

Palynology of the Permian Sanangoe

PALYNOLOGY OF THE PERMIAN SANANGOE- MEFIDEZI COAL BASIN,TETE PROVINCE, MOZAMBIQUE AND CORRELATIONS WITH GONDWANAN MICROFLORAL ASSEMBLAGES Kierra Caprice Mahabeer A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Science, University of the Witwatersrand, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science June, 2017 The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. Declaration I hereby certify that this Dissertation is my own unaided work. It is being submitted for the degree of Master of Science at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any degree or examination at any other University. aT Kierra Caprice Mahabeer June 2017 n Acknowledgements My deepest gratitude goes to my supervisors Prof. Marion Bamford and Dr. Natasha Barbolini. Without their help and guidance this dissertation would not be possible. Thank you for always pushing me further and making me a better researcher. Thanks also goes to Dr. Jennifer Fitchett for the R script as well as for training in the statistical programs used in this study. Thank you to Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (Mozambique Limitada) for access to core. Thank you to Dr. John Hancox for always being willing to assist with any questions and for facilitating access to core and for providing geological core logs. Thanks also goes to Prosper Bande for assistance with laboratory preparation. I am grateful for the financial assistance from the National Research Foundation the Palaeontological Scientific Trust (PAST) and the University of the Witwatersrand.