A Factor Analysis Approach to Modelling the Early Diversification of Terrestrial Vegetation E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embryophytic Sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyfield Cherts

Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences http://journals.cambridge.org/TRE Additional services for Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Embryophytic sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyeld cherts Dianne Edwards Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences / Volume 94 / Issue 04 / December 2003, pp 397 - 410 DOI: 10.1017/S0263593300000778, Published online: 26 July 2007 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0263593300000778 How to cite this article: Dianne Edwards (2003). Embryophytic sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyeld cherts. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences, 94, pp 397-410 doi:10.1017/S0263593300000778 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/TRE, IP address: 131.251.254.13 on 25 Feb 2014 Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences, 94, 397–410, 2004 (for 2003) Embryophytic sporophytes in the Rhynie and Windyfield cherts Dianne Edwards ABSTRACT: Brief descriptions and comments on relationships are given for the seven embryo- phytic sporophytes in the cherts at Rhynie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. They are Rhynia gwynne- vaughanii Kidston & Lang, Aglaophyton major D. S. Edwards, Horneophyton lignieri Barghoorn & Darrah, Asteroxylon mackiei Kidston & Lang, Nothia aphylla Lyon ex Høeg, Trichopherophyton teuchansii Lyon & Edwards and Ventarura lyonii Powell, Edwards & Trewin. The superb preserva- tion of the silica permineralisations produced in the hot spring environment provides remarkable insights into the anatomy of early land plants which are not available from compression fossils and other modes of permineralisation. -

Additional Observations on Zosterophyllum Yunnanicum Hsü from the Lower Devonian of Yunnan, China

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/77818/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Edwards, Dianne, Yang, Nan, Hueber, Francis M. and Li, Cheng-Sen 2015. Additional observations on Zosterophyllum yunnanicum Hsü from the Lower Devonian of Yunnan, China. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 221 , pp. 220-229. 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.03.007 file Publishers page: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.03.007 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.revpalbo.2015.03.007> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. @’ Additional observations on Zosterophyllum yunnanicum Hsü from the Lower Devonian of Yunnan, China Dianne Edwardsa, Nan Yangb, Francis M. Hueberc, Cheng-Sen Lib a*School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3AT, UK b Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China cNational Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 20560-0121, USA * Corresponding author, Tel.: +44 29208742564, Fax.: +44 2920874326 E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Investigation of unfigured specimens in the original collection of Zosterophyllum yunnanicum Hsü 1966 from the Lower Devonian (upper Pragian to basal Emsian) Xujiachong Formation, Qujing District, Yunnan, China has provided further data on both sporangial and stem anatomy. -

JUDD W.S. Et. Al. (2002) Plant Systematics: a Phylogenetic Approach. Chapter 7. an Overview of Green

UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS An Overview of Green Plant Phylogeny he word plant is commonly used to refer to any auto- trophic eukaryotic organism capable of converting light energy into chemical energy via the process of photosynthe- sis. More specifically, these organisms produce carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water in the presence of chlorophyll inside of organelles called chloroplasts. Sometimes the term plant is extended to include autotrophic prokaryotic forms, especially the (eu)bacterial lineage known as the cyanobacteria (or blue- green algae). Many traditional botany textbooks even include the fungi, which differ dramatically in being heterotrophic eukaryotic organisms that enzymatically break down living or dead organic material and then absorb the simpler products. Fungi appear to be more closely related to animals, another lineage of heterotrophs characterized by eating other organisms and digesting them inter- nally. In this chapter we first briefly discuss the origin and evolution of several separately evolved plant lineages, both to acquaint you with these important branches of the tree of life and to help put the green plant lineage in broad phylogenetic perspective. We then focus attention on the evolution of green plants, emphasizing sev- eral critical transitions. Specifically, we concentrate on the origins of land plants (embryophytes), of vascular plants (tracheophytes), of 1 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2 CHAPTER SEVEN seed plants (spermatophytes), and of flowering plants dons.” In some cases it is possible to abandon such (angiosperms). names entirely, but in others it is tempting to retain Although knowledge of fossil plants is critical to a them, either as common names for certain forms of orga- deep understanding of each of these shifts and some key nization (e.g., the “bryophytic” life cycle), or to refer to a fossils are mentioned, much of our discussion focuses on clade (e.g., applying “gymnosperms” to a hypothesized extant groups. -

Chapter 23: the Early Tracheophytes

Chapter 23 The Early Tracheophytes THE LYCOPHYTES Lycopodium Has a Homosporous Life Cycle Selaginella Has a Heterosporous Life Cycle Heterospory Allows for Greater Parental Investment Isoetes May Be the Only Living Member of the Lepidodendrid Group THE MONILOPHYTES Whisk Ferns Ophioglossalean Ferns Horsetails Marattialean Ferns True Ferns True Fern Sporophytes Typically Have Underground Stems Sexual Reproduction Usually Is Homosporous Fern Have a Variety of Alternative Means of Reproduction Ferns Have Ecological and Economic Importance SUMMARY PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Sporophyte Prominence and Survival on Land PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Coal, Smog, and Forest Decline THE OCCUPATION OF THE LAND PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE The First Tracheophytes Were ENVIRONMENT: Diversity Among the Ferns Rhyniophytes Tracheophytes Became Increasingly Better PLANTS, PEOPLE, AND THE Adapted to the Terrestrial Environment ENVIRONMENT: Fern Spores Relationships among Early Tracheophytes 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. Tracheophytes, also called vascular plants, possess lignified water-conducting tissue (xylem). Approximately 14,000 species of tracheophytes reproduce by releasing spores and do not make seeds. These are sometimes called seedless vascular plants. Tracheophytes differ from bryophytes in possessing branched sporophytes that are dominant in the life cycle. These sporophytes are more tolerant of life on dry land than those of bryophytes because water movement is controlled by strongly lignified vascular tissue, stomata, and an extensive cuticle. The gametophytes, however still require a seasonally wet habitat, and water outside the plant is essential for the movement of sperm from antheridia to archegonia. 2. The rhyniophytes were the first tracheophytes. They consisted of dichotomously branching axes, lacking roots and leaves. They are all extinct. -

System Klasyfikacji Organizmów

1 SYSTEM KLASYFIKACJI ORGANIZMÓW Nie ma dziś ogólnie przyjętego systemu klasyfikacji organizmów. Nie udaje się osiągnąć zgodności nie tylko w odniesieniu do zakresów i rang poszczególnych taksonów, ale nawet co do zasad metodologicznych, na których klasyfikacja powinna być oparta. Zespołowe dzieła przeglądowe z reguły prezentują odmienne i wzajemnie sprzeczne podejścia poszczególnych autorów, bez nadziei na consensus. Nie ma więc mowy o skompilowaniu jednolitego schematu klasyfikacji z literatury i system przedstawiony poniżej nie daje nadziei na zaakceptowanie przez kogokolwiek poza kompilatorem. Przygotowany został w oparciu o kilka zasad (skądinąd bardzo kontrowersyjnych): (1) Identyfikowanie ga- tunków i ich klasyfikowanie w jednostki rodzajowe, rodzinowe czy rzędy jest zadaniem specjalistów i bez szcze- gółowych samodzielnych studiów nie można kwestionować wyników takich badań. (2) Podział świata żywego na królestwa, typy, gromady i rzędy jest natomiast domeną ewolucjonistów i dydaktyków. Powody, które posłużyły do wydzielenia jednostek powinny być jasno przedstawialne i zrozumiałe również dla niespecjalistów, albowiem (3) podstawowym zadaniem systematyki jest ułatwianie laikom i początkującym badaczom poruszanie się w obezwładniającej złożoności świata żywego. Wątpliwe jednak, by wystarczyło to do stworzenia zadowalającej klasyfikacji. W takiej sytuacji można jedynie przypomnieć, że lepszy ułomny system, niż żaden. Królestwo PROKARYOTA Chatton, 1938 DNA wyłącznie w postaci kolistej (genoforów), transkrypcja nie rozdzielona przestrzennie od translacji – rybosomy w tym samym przedzia- le komórki, co DNA. Oddział CYANOPHYTA Smith, 1938 (Myxophyta Cohn, 1875, Cyanobacteria Stanier, 1973) Stosunkowo duże komórki, dwuwarstwowa błona (Gram-ujemne), wewnętrzna warstwa mureinowa. Klasa CYANOPHYCEAE Sachs, 1874 Rząd Stigonematales Geitler, 1925; zigen – dziś Chlorofil a na pojedynczych tylakoidach. Nitkowate, rozgałęziające się, cytoplazmatyczne połączenia mię- Rząd Chroococcales Wettstein, 1924; 2,1 Ga – dziś dzy komórkami, miewają heterocysty. -

Dr. Sahanaj Jamil Associate Professor of Botany M.L.S.M. College, Darbhanga

Subject BOTANY Paper No V Paper Code BOT521 Topic Taxonomy and Diversity of Seed Plant: Gymnosperms & Angiosperms Dr. Sahanaj Jamil Associate Professor of Botany M.L.S.M. College, Darbhanga BOTANY PG SEMESTER – II, PAPER –V BOT521: Taxonomy and Diversity of seed plants UNIT- I BOTANY PG SEMESTER – II, PAPER –V BOT521: Taxonomy and Diversity of seed plants Classification of Gymnosperms. # Robert Brown (1827) for the first time recognized Gymnosperm as a group distinct from angiosperm due to the presence of naked ovules. BENTHAM and HOOKSER (1862-1883) consider them equivalent to dicotyledons and monocotyledons and placed between these two groups of angiosperm. They recognized three classes of gymnosperm, Cyacadaceae, coniferac and gnetaceae. Later ENGLER (1889) created a group Gnikgoales to accommodate the genus giankgo. Van Tieghem (1898) treated Gymnosperm as one of the two subdivision of spermatophyte. To accommodate the fossil members three more classes- Pteridospermae, Cordaitales, and Bennettitales where created. Coulter and chamberlain (1919), Engler and Prantl (1926), Rendle (1926) and other considered Gymnosperm as a division of spermatophyta, Phanerogamia or Embryoptyta and they further divided them into seven orders: - i) Cycadofilicales ii) Cycadales iii) Bennettitales iv) Ginkgoales v) Coniferales vi) Corditales vii) Gnetales On the basis of wood structure steward (1919) divided Gymnosperm into two classes: - i) Manoxylic ii) Pycnoxylic The various classification of Gymnosperm proposed by various workers are as follows: - i) Sahni (1920): - He recognized two sub-divison in gymnosperm: - a) Phylospermae b) Stachyospermae BOTANY PG SEMESTER – II, PAPER –V BOT521: Taxonomy and Diversity of seed plants ii) Classification proposed by chamber lain (1934): - He divided Gymnosperm into two divisions: - a) Cycadophyta b) Coniterophyta iii) Classification proposed by Tippo (1942):- He considered Gymnosperm as a class of the sub- phylum pteropsida and divided them into two sub classes:- a) Cycadophyta b) Coniferophyta iv) D. -

Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation

i1 Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation William A. DiMichele, William E. Stein, and Richard M. Bateman DiMichele, W.A., Stein, W.E., and Bateman, R.M. 2001. Ecological sorting of vascular plant classes during the Paleozoic evolutionary radiation. In: W.D. Allmon and D.J. Bottjer, eds. Evolutionary Paleoecology: The Ecological Context of Macroevolutionary Change. Columbia University Press, New York. pp. 285-335 THE DISTINCTIVE BODY PLANS of vascular plants (lycopsids, ferns, sphenopsids, seed plants), corresponding roughly to traditional Linnean classes, originated in a radiation that began in the late Middle Devonian and ended in the Early Carboniferous. This relatively brief radiation followed a long period in the Silurian and Early Devonian during wrhich morphological complexity accrued slowly and preceded evolutionary diversifications con- fined within major body-plan themes during the Carboniferous. During the Middle Devonian-Early Carboniferous morphological radiation, the major class-level clades also became differentiated ecologically: Lycopsids were cen- tered in wetlands, seed plants in terra firma environments, sphenopsids in aggradational habitats, and ferns in disturbed environments. The strong con- gruence of phylogenetic pattern, morphological differentiation, and clade- level ecological distributions characterizes plant ecological and evolutionary dynamics throughout much of the late Paleozoic. In this study, we explore the phylogenetic relationships and realized ecomorphospace of reconstructed whole plants (or composite whole plants), representing each of the major body-plan clades, and examine the degree of overlap of these patterns with each other and with patterns of environmental distribution. We conclude that 285 286 EVOLUTIONARY PALEOECOLOGY ecological incumbency was a major factor circumscribing and channeling the course of early diversification events: events that profoundly affected the structure and composition of modern plant communities. -

The Classification of Early Land Plants-Revisited*

The classification of early land plants-revisited* Harlan P. Banks Banks HP 1992. The c1assificalion of early land plams-revisiled. Palaeohotanist 41 36·50 Three suprageneric calegories applied 10 early land plams-Rhyniophylina, Zoslerophyllophytina, Trimerophytina-proposed by Banks in 1968 are reviewed and found 10 have slill some usefulness. Addilions 10 each are noted, some delelions are made, and some early planls lhal display fealures of more lhan one calegory are Sel aside as Aberram Genera. Key-words-Early land-plams, Rhyniophytina, Zoslerophyllophytina, Trimerophytina, Evolulion. of Plant Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York-5908, U.S.A. 14853. Harlan P Banks, Section ~ ~ ~ <ltm ~ ~-~unR ~ qro ~ ~ ~ f~ 4~1~"llc"'111 ~-'J~f.f3il,!"~, 'i\'1f~()~~<1I'f'I~tl'1l ~ ~1~il~lqo;l~tl'1l, 1968 if ~ -mr lfim;j; <fr'f ~<nftm~~Fmr~%1 ~~ifmm~~-.mtl ~if-.t~m~fuit ciit'!'f.<nftmciit~%1 ~ ~ ~ -.m t ,P1T ~ ~~ lfiu ~ ~ -.t 3!ftrq; ~ ;j; <mol ~ <Rir t ;j; w -.m tl FIRST, may I express my gratitude to the Sahni, to survey briefly the fate of that Palaeobotanical Sociery for the honour it has done reclassification. Several caveats are necessary. I recall me in awarding its International Medal for 1988-89. discussing an intractable problem with the late great May I offer the Sociery sincere thanks for their James M. Schopf. His advice could help many consideration. aspiring young workers-"Survey what you have and Secondly, may I join in celebrating the work and write up that which you understand. The rest will the influence of Professor Birbal Sahni. The one time gradually fall into line." That is precisely what I did I met him was at a meeting where he was displaying in 1968. -

Acaulosporoid Glomeromycotan Spores with a Germination Shield from the 400-Million-Year-Old Rhynie Chert

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. Acaulosporoid glomeromycotan spores with a germination shield from the 400-million- year-old Rhynie chert by Nora Dotzler, Christopher Walker, Michael Krings, Hagen Hass, Hans Kerp, Thomas N. Taylor, Reinhard Agerer 2009 This is the published version of the article, made available with the permission of the publisher. The original published version can be found at the link below. Dotzler, N., Walker, C., Krings, M., Hass, H., Kerp, H., Taylor, T., Agerer, R. 2009. Acaulosporoid glomeromycotan spores with a ger- mination shield from the 400-million-year-old Rhynie chert. Mycol Progress 8:9-18. Published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11557-008-0573-1 Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. Mycol Progress (2009) 8:9–18 DOI 10.1007/s11557-008-0573-1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Acaulosporoid glomeromycotan spores with a germination shield from the 400-million-year-old Rhynie chert Nora Dotzler & Christopher Walker & Michael Krings & Hagen Hass & Hans Kerp & Thomas N. Taylor & Reinhard Agerer Received: 4 June 2008 /Revised: 16 September 2008 /Accepted: 30 September 2008 / Published online: 15 October 2008 # German Mycological Society and Springer-Verlag 2008 Abstract Scutellosporites devonicus from the Early Devo- single or double lobes to tongue-shaped structures usually nian Rhynie chert is the only fossil glomeromycotan spore with infolded margins that are distally fringed or palmate. taxon known to produce a germination shield. -

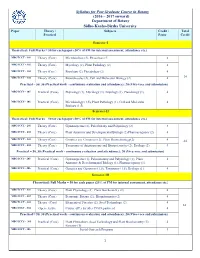

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 Onward)

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 onward) Department of Botany Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University Paper Theory / Subjects Credit / Total Practical Paper Credit Semester-I Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 101 Theory (Core) Microbiology (2), Phycology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 102 Theory (Core) Mycology (2), Plant Pathology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 103 Theory (Core) Bryology (2), Pteridology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 104 Theory (Core) Biomolecules (2), Cell and Molecular Biology (2) 4 24 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 105 Practical (Core) Phycology (1), Mycology (1), Bryology (1), Pteridology (1). 4 MBOTCCS - 106 Practical (Core) Microbiology (1.5), Plant Pathology (1), Cell and Molecular 4 Biology (1.5). Semester-II Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 201 Theory (Core) Gymnosperms (2), Paleobotany and Palynology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 202 Theory (Core) Plant Anatomy and Developmental Biology (2) Pharmacognosy (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 203 Theory (Core) Genetics and Genomics (2), Plant Biotechnology(2) 4 24 MBOTCCT - 204 Theory (Core) Taxonomy of Angiosperms and Biosystematics (2), Ecology (2) 4 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 205 Practical (Core) Gymnosperms (1), Palaeobotany and Palynology (1), Plant 4 Anatomy & Developmental Biology (1), Pharmacognosy (1). MBOTCCS - 206 Practical (Core) Genetics and Genomics (1.5), Taxonomy (1.5), Ecology (1). 4 Semester-III Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 301 Theory (Core) Plant Physiology (2), Plant Biochemistry (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 302 Theory (Core) Economic Botany (2), Bioinformatics (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 303 Theory (Core) Elements of Forestry (2), Seed Technology (2). -

Syllabus M.Sc. Botany (Choice Based Credit System)

Syllabus M.Sc. Botany (Choice Based Credit System) (To be implemented from the Academic Year 2017-18) DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY UNIVERSITY OF ALLAHABAD Page 1 of 21 DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY UNIVERSITY OF ALLAHABAD M.Sc. Syllabus (Choice Based Credit System) (To be implemented from the Academic Year 2017-18) Semester – I Course Code Marks Course Title Credits BOT501 100 Phycology and Limnology 3 BOT502 100 Mycology and Plant Pathology 3 BOT503 100 Bryology and Pteridology 3 BOT504 100 Gymnosperm and Palaeobotany 3 BOT531 100 Lab Work I (based on Course BOT501 and BOT502) 4 (Excursion/field work/ Project) BOT532 100 Lab Work II (based on Course BOT503 and BOT504) 4 (Excursion/field work/Project) Total credits 20 Semester – II Course Code Marks Course Title Credits BOT505 100 Plant Morphology and Anatomy 3 BOT506 100 Reproductive Biology, Morphogenesis and Tissue culture 3 BOT507 100 Taxonomy of Angiosperm and Economic Botany 3 BOT508 100 Ecology and Phytogeography 3 BOT533 100 Lab Work III (based on Course BOT505 and BOT506) 4 (Field work/ Project) BOT534 100 Lab Work IV (based on Course BOT507 and BOT508) 4 (Field work/ Project) Total credits 20 Semester – III Course Code Marks Course Title Credits BOT601 100 Plant Physiology 3 BOT602 100 Plant Biochemistry and Biochemical Techniques 3 BOT603 100 Cytogenetics, Plant Breeding and Biostatistics 3 BOT604 100 Microbiology 3 BOT631 100 Lab Work V (based on Course BOT601 and BOT602) 4 BOT632 100 Lab Work VI (based on Course BOT603 and BOT604) 4 Total credits 20 Semester – IV Course Code Marks Course -

A Reappraisal of Mississippian (Tournaisian and Visean) Adpression Floras from Central and Northwestern Europe

Zitteliana A 54 (2014) 39 A reappraisal of Mississippian (Tournaisian and Visean) adpression floras from central and northwestern Europe Maren Hübers1, Benjamin Bomfleur2*, Michael Krings3, Christian Pott2 & Hans Kerp1 1Forschungsstelle für Paläobotanik am Geologisch-Paläontologischen Institut, Westfälische Zitteliana A 54, 39 – 52 Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Heisenbergstraße 2, 48149 Münster, Germany München, 31.12.2014 2Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Paleobiology, Box 50007, SE-104 05, Stockholm, Sweden Manuscript received 3Department für Geo- und Umweltwissenschaften, Paläontologie und Geobiologie, Ludwig- 01.02.2014; revision Maximilians-Universität, and Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie, Richard- accepted 07.04.2014 Wagner-Straße 10, 80333 Munich, Germany ISSN 1612 - 412X *Author for correspondence and reprint requests: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Mississippian plant fossils are generally rare, and in central and northwestern Europe especially Tournaisian to middle Visean fossil floras are restricted to isolated occurrences. While sphenophytes and lycophytes generally are represented by only a few widespread and long-ranging taxa such as Archaeocalamites radiatus, Sphenophyllum tenerrimum and several species of Lepidodendropsis and Lepido- dendron, Visean floras in particular show a remarkably high diversity of fern-like foliage, including filiform types (Rhodea, Diplotmema), forms with bipartite fronds (Sphenopteridium, Diplopteridium, Spathulopteris, Archaeopteridium), others with monopodial, pinnate fronds (Anisopteris, Fryopsis) and still others characterized by several-times pinnate fronds (e.g., Adiantites, Triphyllopteris, Sphenopteris, Neu- ropteris). Most of these leaf types have been interpreted as belonging to early seed ferns, whereas true ferns seem to have been rare or lacking in impression/compression floras. In the upper Visean, two types of plant assemblages can be distinguished, i.e., the northern Kohlenkalk-type and the south-eastern Kulm-type assemblage.