Anthropology at Borders: Power, Culture, Memories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bischofswerda the Town and Its People Contents

Bischofswerda The town and its people Contents 0.1 Bischofswerda ............................................. 1 0.1.1 Geography .......................................... 1 0.1.2 History ............................................ 1 0.1.3 Sights ............................................. 2 0.1.4 Economy and traffic ...................................... 2 0.1.5 Culture and sports ....................................... 3 0.1.6 Partnership .......................................... 3 0.1.7 Personality .......................................... 3 0.1.8 Notes ............................................. 4 0.1.9 External links ......................................... 4 0.2 Großdrebnitz ............................................. 4 0.2.1 History ............................................ 4 0.2.2 People ............................................ 5 0.2.3 Literature ........................................... 6 0.2.4 Footnotes ........................................... 6 0.3 Wesenitz ................................................ 6 0.3.1 Geography .......................................... 6 0.3.2 Touristic Attractions ..................................... 6 0.3.3 Historical Usage ....................................... 7 0.3.4 Fauna ............................................. 7 0.3.5 References .......................................... 7 1 People born in or working for Bischofswerda 8 1.1 Abd-ru-shin .............................................. 8 1.1.1 Life, Publishing, Legacy ................................... 8 1.1.2 Legacy -

Del Libro Impreso Al Libro Digital, by Marie Lebert

Project Gutenberg's Del libro impreso al libro digital, by Marie Lebert This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org ** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below ** ** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. ** Title: Del libro impreso al libro digital Author: Marie Lebert Release Date: May 28, 2011 [EBook #34091] Language: Spanish Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DEL LIBRO IMPRESO AL LIBRO DIGITAL *** Produced by Al Haines DEL LIBRO IMPRESO AL LIBRO DIGITAL MARIE LEBERT NEF, Universidad de Toronto, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Marie Lebert. Todos los derechos reservados. --- Este libro está dedicado a todas las personas que han contestado a mis preguntas durante los últimos diez años en Europa, en las Américas, en África y en Asia. Gracias por el tiempo que me han dedicado, y por su amistad. --- El libro impreso tiene cinco siglos y medio de edad. El libro digital tiene ya 40 años. Hoy en día uno puede leer un libro en su ordenador, en su asistente personal (PDA), en su teléfono móvil, en su smartphone o en su tableta de lectura. Es el viaje "virtual" el que vamos a emprender en este libro, el que se ha basado en unas miles de horas de navegación en la web durante diez años y en una centena de entrevistas llevadas a cabo por el mundo entero. -

Eastern Europe

NAZI PLANS for EASTE RN EUR OPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies SECRET NAZI PLANS for EASTERN EUROPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies hy Ihor Kamenetsky ---- BOOKMAN ASSOCIATES :: New York Copyright © 1961 by Ihor Kamenetsky Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 61-9850 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY UNITED PRINTING SERVICES, INC. NEW HAVEN, CONN. TO MY PARENTS Preface The dawn of the twentieth century witnessed the climax of imperialistic competition in Europe among the Great Pow ers. Entrenched in two opposing camps, they glared at each other over mountainous stockpiles of weapons gathered in feverish armament races. In the one camp was situated the Triple Entente, in the other the Triple Alliance of the Central Powers under Germany's leadership. The final and tragic re sult of this rivalry was World War I, during which Germany attempted to realize her imperialistic conception of M itteleuropa with the Berlin-Baghdad-Basra railway project to the Near East. Thus there would have been established a transcontinental highway for German industrial and commercial expansion through the Persian Gull to the Asian market. The security of this highway required that the pressure of Russian imperi alism on the Middle East be eliminated by the fragmentation of the Russian colonial empire into its ethnic components. Germany· planned the formation of a belt of buffer states ( asso ciated with the Central Powers and Turkey) from Finland, Beloruthenia ( Belorussia), Lithuania, Poland to Ukraine, the Caucasus, and even to Turkestan. The outbreak and nature of the Russian Revolution in 1917 offered an opportunity for Imperial Germany to realize this plan. -

Charles C Thomas Publisher Cable : " Thomas • Springfield'" Telephone: 544-7110 (Area Code 217)

CHARLES C THOMAS PUBLISHER CABLE : " THOMAS • SPRINGFIELD'" TELEPHONE: 544-7110 (AREA CODE 217) CHARLES C THOMAS BOOKS, MONOGRAPHS and JOURNALS in MEDICINE, N P THOMAS SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY and PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PA YNE E L THOMAS Reply to HOME OFFICE 301-327 EAST LAWRENCE AVENUE • SPRINGFIELD-ILLINOIS 62703 November 3, 1971 MLss Jeanette Oberle p Books and Series University Microfilms ^ A Xerox Company Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Dear Kiss Oberle; Thank you for your letter of September 29, concerning your request to reproduce copies of the book by Professor Irving Horowitz, PHILOSOPHY, SCIENCE AfilO SOCIOLOGY OF KfoOWIJEDGE. We do ow« the copyright to Professor Horowitz* book, however we prefer that the author also gives his approval when copy is reproduced. If Professor Horowitz expects to be paid a 1056 royalty directly from you, I can well understand your decision to cancel the agreement. I am writing to Professor Horowitz to let him know that in such agreements, you pay the royalty directly to us as the publisher and holder of the copyright. We then, of course, pay him a per cent of the royalty. I will ask Professor Horowitz to contact you directly if he will allow you to reproduce copies of the book on this basis. If you do not hear from him, you may wish to cancel our agree ment. With kindest regards. Sincerely, CHARLES C THOMAS, PUBLISHER Lawrence Bentley dvertising & Sales A HCXM BV fBANt LLOY0 Wfi : -NATC DISTRIBUTORS THROUGHOUT THE WORLD ALABAMA, BIRMINGHAM E. F. Mahady Companv COLUMBUS, Long's College Book Com BALBOA. Cathedral Book Comer Libreria Dino Rossi University of Alabama Medical MICHIGAN pany CANARY ISLANDS Libr. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/23/2021 09:14:00PM Via Free Access

russian history 44 (2017) 209-242 brill.com/ruhi What Do We Know about *Čьrnobogъ and *Bělъ Bogъ? Yaroslav Gorbachov Assistant Professor of Linguistics, Department of Linguistics, University of Chicago [email protected] Abstract As attested, the Slavic pantheon is rather well-populated. However, many of its nu- merous members are known only by their names mentioned in passing in one or two medieval documents. Among those barely attested Slavic deities, there are a few whose very existence may be doubted. This does not deter some scholars from articulating rather elaborate theories about Slavic mythology and cosmology. The article discusses two obscure Slavic deities, “Black God” and “White God,” and, in particular, reexamines the extant primary sources on them. It is argued that “Black God” worship was limited to the Slavic North-West, and “White God” never existed. Keywords Chernobog – Belbog – Belbuck – Tjarnaglófi – Vij – Slavic dualism Introduction A discussion of Slavic mythology and pantheons is always a difficult, risky, and thankless business. There is no dearth of gods to talk about. In the literature they are discussed with confidence and, at times, some bold conclusions about Slavic cosmology are made, based on the sheer fact of the existence of a par- ticular deity. In reality, however, many of the “known” Slavic gods are not much more than a bare theonym mentioned once or twice in what often is a late, un- reliable, or poorly interpretable document. The available evidence is undeni- ably scanty and the dots to be connected are spaced far apart. Naturally, many © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2017 | doi 10.1163/18763316-04402011Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 09:14:00PM via free access <UN> 210 Gorbachov Slavic mythologists have succumbed to an understandable urge to supply the missing fragments by “reconstructing” them. -

15287/13 BM/Lm 1 DG D 1 a COUNCIL of the EUROPEAN

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 24 October 2013 THE EUROPEAN UNION 15287/13 FRONT 159 COMIX 572 NOTE from: Polish delegation to: Delegations/Mixed Committee (EU-Iceland/Liechtenstein/Norway/Switzerland) Subject: Temporary reintroduction of border controls at the Polish internal borders in accordance with Articles 23(1) and 24 of Regulation (EC) No 562/2006 establishing a Community Code on the rules governing the movement of persons across borders (Schengen Borders Code) Delegations will find attached a copy of the letters received by the General Secretariat of the Council on 23 October 2013 regarding temporary reintroduction of border controls by Poland at its internal borders between 8-23 November 2013. 15287/13 BM/lm 1 DG D 1 A EN/PL 15287/13 BM/lm 2 ANNEX DG D 1 A EN/PL 15287/13 BM/lm 3 ANNEX DG D 1 A EN/PL 15287/13 BM/lm 4 ANNEX DG D 1 A EN/PL List of authorized crossing-points Explanatory notes: D – road crossing-point K – rail crossing-point R – river crossing-point M – maritime crossing-point L – air crossing-point Authorized crossing-points Type of traffic Opening hours Name Type Border section with the Czech Republic people and goods, 1 Jaworzynka D 24 hours as of the road parameters people and goods, 2 Jasnowice D 24 hours as of the road parameters people and goods, 3 Stożek D 24 hours as of the road parameters people and goods, 4 Beskidek D 24 hours as of the road parameters people and goods, 5 Leszna Górna D 24 hours as of the road parameters people and goods, 6 Puńców D 24 hours as of the road parameters people and goods, 7 Cieszyn -

Ewidencja Obiektów Zabytkowych Powiatu Cieszyńskiego

EWIDENCJA OBIEKTÓW ZABYTKOWYCH POWIATU CIESZYŃSKIEGO Opracowanie wykonane w oparciu o wojewódzką i gminną ewidencję zabytków w Wydziale Kultury, Sportu, Turystyki i Informacji Starostwa Powiatowego w Cieszynie przez Łukasza Konarzewskiego Cieszyn, czerwiec – lipiec 2010 r. Ostatnio aktualizowane w listopadzie 2012 r. SPIS TREŚCI: Spis treści ....................................... 2 str. Wstęp ............................................. 3 str. Ważniejsze skróty .......................... 3 str. Cieszyn .......................................... 4 str. Gmina Brenna .............................. 20 str. Gmina Chybie............................... 23 str. Gmina Dębowiec........................... 25 str. Gmina Goleszów........................... 30 str. Gmina Hażlach.............................. 36 str. Gmina Istebna............................... 39 str. Miasto i Gmina Skoczów.............. 48 str. Miasto i Gmina Strumień.............. 57 str. Miasto Ustroń................................ 63 str. Miasto Wisła................................. 72 str. Gmina Zebrzydowice.................... 77 str. 2 Wstęp Ewidencja zabytków powiatu cieszyńskiego stanowi zestawienie obiektów nieruchomych, będących wytworem człowieka, głównie z zakresu architektury i budownictwa o różnych funkcjach użytkowych, posiadających walory historyczne i artystyczne. Zestawienie to powstało na podstawie zgromadzonych w poprzednich latach materiałów oraz informacji pochodzących z Delegatury w Bielsku-Białej – Wojewódzkiego Urzędu Ochrony Zabytków w Katowicach, a także -

The Interwar Spa Resort Wisła – the Degree of Cultural Environment Preservation

ANNA PAWLAK∗ THE INTERWAR SPA RESORT WISŁA – THE DEGREE OF CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT PRESERVATION MIĘDZYWOJENNE UZDROWISKO WISŁA – STAN ZACHOWANIA ŚRODOWISKA KULTUROWEGO Abstract The aim of the article is to present and highlight the cultural heritage of Wisła as an example of an interwar spa resort designed from scratch, which in the contemporary times has been to a large extent destroyed. The urban principles and the construction projects realized in result of the regulation plans of the 20s and 30s of the 20th century created a coherent concept of the town’s growth based on spatial order and harmony with the natural environment, a concept which was consistently executed. The Author emphasizes that at present, owing to erroneous planning decisions, the proportions between the developed areas and the natural environment have been distorted, and the stylistic uniformity of buildings has been disfigured in the process of their modernization. Keywords: holiday resort, regulation plaus, cultural heritage Streszczenie Celem artykułu jest zwrócenie uwagi na dziedzictwo kulturowe Wisły, jako przykładu projektowanego od podstaw międzywojennego uzdrowiska, które w czasach współczesnych uległo znacznej destrukcji. Założenia urbanistyczne i realizacje budowlane powstałe w efekcie planów regulacyjnych z lat 20. i 30. XX wieku stworzyły spójną koncepcję rozwoju miasta opartą na ładzie przestrzennym oraz harmonii ze śro- dowiskiem przyrodniczym i konsekwentnie były egzekwowane. Autorka podkreśla, że obecnie w wyniku nieprawidłowych decyzji planistycznych zniekształcone zostały proporcje miedzy terenami zabudowany- mi i środowiskiem naturalnym a poprzez modernizacje obiektów zaburzono ich jednorodność stylistyczną. Słowa kluczowe: miejscowość wypoczynkowa, plany regulacyjne, dziedzictwo kulturowe ∗ Ph.D. Eng. Arch. Anna Pawlak, Institute of Cities and Regions Design, Faculty of Architecture, Cracow University of Technology. -

Ethnic and Regional Identity in Polish Part of Spiš Region (On the Example of Jurgów Village)

78 ETHNOLOGIA ACTUALIS Vol. 14, No. 1/2014 VOJTECH BAGÍN Ethnic and Regional Identity in Polish Part of Spiš Region (on the Example of Jurgów Village) Ethnic and Regional Identity in Polish Part of Spiš Region (On the Example of Jurgów Village) VOJTECH BAGÍN Department of Ethnology and Museology, Comenius University in Bratislava [email protected] ABSTRACT In my study I am focusing on the issue of national and regional identity of Spiš region inhabitants. The researched Jurgów village belongs to territory situated on the frontier between two states and at the same time between two regions. In the study I analyze the question of stereotypes present in the locality concerning gorals from the neighbouring Podhale region and Slovak part of Spiš region. In addition to that I deal with analysis of importance and understanding of space and border for the identity of local population. On the basis of the empirical data analysis results I observe that the identity of the researched village population is shaped by the fact that it belongs to the frontier territory where cross- border cultural and social interaction occurs. KEY WORDS: ethnic identity, stereotypes, space, Jurgów, Spiš region Introduction In Slovak ethnological science, the area of Slovak-Polish borderlands of Spiš region has been researched only to a small extent. However, on the Polish side of the border occurs quite the opposite. In Polish science there have been issued various publications DOI: 10.2478/eas-2014-0005 © University of SS. Cyril and Methodius in Trnava. All rights reserved. 79 ETHNOLOGIA ACTUALIS Vol. 14, No. 1/2014 VOJTECH BAGÍN Ethnic and Regional Identity in Polish Part of Spiš Region (on the Example of Jurgów Village) concerned with this region not only in the past but also in the present1. -

Bruno Kamiński

Fear Management. Foreign threats in the postwar Polish propaganda – the influence and the reception of the communist media (1944 -1956) Bruno Kamiński Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 14 June 2016 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Fear Management. Foreign threats in the postwar Polish propaganda – the influence and the reception of the communist media (1944 -1956) Bruno Kamiński Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Pavel Kolář (EUI) - Supervisor Prof. Alexander Etkind (EUI) Prof. Anita Prażmowska (London School Of Economics) Prof. Dariusz Stola (University of Warsaw and Polish Academy of Science) © Bruno Kamiński, 2016 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I <Bruno Kamiński> certify that I am the author of the work < Fear Management. Foreign threats in the postwar Polish propaganda – the influence and the reception of the communist media (1944 -1956)> I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. -

Rozkład Jazdy Skoczów-Kowale-Skoczów

D D D Skoczów Dworzec Autobusowy 07:30 13:25 16:40 Skoczów Szkoła Kiczycka 02 07:32 13:27 16:42 Skoczów I Kiczycka 04 07:34 13:29 16:44 Kiczyce Pierściecka 06 07:36 13:31 16:46 Pierściec Dworzec Kolejowy Skoczowska 08 07:38 13:33 16:48 Pierściec Skrzyżowanie Skoczowska 10 07:40 13:35 16:50 Pierściec Uchylany Landecka 12 07:42 13:37 16:52 Pierściec Osiedle Landecka 14 07:43 13:38 16:53 Pierściec Brzózka Landecka 15 07:44 13:39 16:54 Pierściec Osiedle Landecka 13 07:45 13:40 16:55 Pierściec Uchylany Landecka 11 07:46 13:41 16:56 Pierściec Skrzyżowanie I Ks. H. Sobeckiego 02 07:48 13:43 16:58 Pierściec Las Kowalska 04 07:50 13:45 17:00 Kowale Stawy Kowalska 06 07:51 13:46 17:01 Kowale Spółdzielnia 07:53 13:48 17:03 Kowale Stawy Kowalska 05 07:54 13:49 17:04 Pierściec Las Kowalska 03 07:56 13:51 17:06 Pierściec Skrzyżowanie I Ks. H. Sobeckiego 01 07:57 13:52 17:07 Pierściec Dworzec Kolejowy Skoczowska 07 07:59 13:54 17:09 Kiczyce Pierściecka 05 08:01 13:56 17:11 Skoczów I Kiczycka 03 08:03 13:58 17:13 Skoczów Szkoła Kiczycka 01 08:05 14:00 17:15 Skoczów Dworzec Autobusowy 08:07 14:02 17:17 Rozkład ważny od 01.07 do 31.08.2020 r. Legenda: D - kursuje w dni robocze od poniedziałku do piątku DAS Katarzyna Kwiczala Gumna ul. -

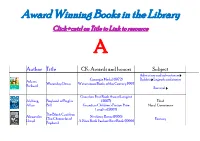

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+Cntrl on Title to Link to Resource A

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+cntrl on Title to Link to resource A Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Adventure and adventurers › Carnegie Medal (1972) Rabbits › Legends and stories Adams, Watership Down Waterstones Books of the Century 1997 Richard Survival › Guardian First Book Award Longlist Ahlberg, Boyhood of Buglar (2007) Thief Allan Bill Guardian Children's Fiction Prize Moral Conscience Longlist (2007) The Black Cauldron Alexander, Newbery Honor (1966) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1966) Prydain) Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject The Book of Three Alexander, A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1965) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd Prydain Book 1) A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1967) Alexander, Castle of Llyr Fantasy Lloyd Princesses › A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1968) Taran Wanderer (The Alexander, Fairy tales Chronicles of Lloyd Fantasy Prydain) Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2003) Whitbread (Children's Book, 2003) Boston Globe–Horn Book Award Almond, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 › The Fire-eaters (Fiction, 2004) David Great Britain › History Nestlé Smarties Book Prize (Gold Award, 9-11 years category, 2003) Whitbread Shortlist (Children's Book, Adventure and adventurers › Almond, 2000) Heaven Eyes Orphans › David Zilveren Zoen (2002) Runaway children › Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2000) Amateau, Chancey of the SIBA Book Award Nominee courage, Gigi Maury River Perseverance Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Angeli, Newbery Medal (1950) Great Britain › Fiction. › Edward III, Marguerite The Door in the Wall Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1961) 1327-1377 De A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1950) Physically handicapped › Armstrong, Newbery Honor (2006) Whittington Cats › Alan Newbery Honor (1939) Humorous stories Atwater, Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1958) Mr.