MANAGING BORDERS in an INCREASINGLY BORDERLESS WORLD Randall Hansen and Demetrios G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Del Libro Impreso Al Libro Digital, by Marie Lebert

Project Gutenberg's Del libro impreso al libro digital, by Marie Lebert This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org ** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below ** ** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. ** Title: Del libro impreso al libro digital Author: Marie Lebert Release Date: May 28, 2011 [EBook #34091] Language: Spanish Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DEL LIBRO IMPRESO AL LIBRO DIGITAL *** Produced by Al Haines DEL LIBRO IMPRESO AL LIBRO DIGITAL MARIE LEBERT NEF, Universidad de Toronto, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Marie Lebert. Todos los derechos reservados. --- Este libro está dedicado a todas las personas que han contestado a mis preguntas durante los últimos diez años en Europa, en las Américas, en África y en Asia. Gracias por el tiempo que me han dedicado, y por su amistad. --- El libro impreso tiene cinco siglos y medio de edad. El libro digital tiene ya 40 años. Hoy en día uno puede leer un libro en su ordenador, en su asistente personal (PDA), en su teléfono móvil, en su smartphone o en su tableta de lectura. Es el viaje "virtual" el que vamos a emprender en este libro, el que se ha basado en unas miles de horas de navegación en la web durante diez años y en una centena de entrevistas llevadas a cabo por el mundo entero. -

Montaldo Solution Interim Report

Considerations for the National Migrant Integration Strategy 2015-2020 (Malta) Author: Norman Scicluna Date: 30 May 2015 Version: V1.0 Considerations for the National Migrant Integration Strategy V1.0 Norman Scicluna CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE NATIONAL MIGRANT INTEGRATION STRATEGY 2015-2020 (MALTA) Authored by Norman Scicluna Disclaimer & Scope This document is drawn up in response to the request for Consultation on the National Migrant Integration Strategy 2015-2020 as outlined in the call for Consultation by the Ministry for Social Dialogue and Department, Consumer Affairs and Civil Liberties, first published on the 5th of May 2015. It is drawn up by the author (Norman Scicluna) on his own behalf and on his own initiative. For this purpose, it reflects the author’s own opinions and ideas and may not necessarily be representative of any public or private group, forum, party or association with which the author may have any membership in, affiliation or connection with, or representation of, whether such a relationship is actual, assumed or implied. Contact Norman Scicluna – (128362M) Tel: +356-79705778 Email: [email protected] Copyright & Publication Copyright © Norman Scicluna, 2015 The purpose of this document is to be made available to the general public in order to be a basis for further discussion throughout the Immigrant Integration Strategy formation and implementation process. For this purpose this document may be reproduced in its entirety, as-is and with due attribution to the author. Reproduction in part is by specific authorization from the author. Note: All websites quoted and referenced in this document are as at the time of writing – May 2015 and are subject to be modified, added to, or removed accordingly, Document for Public Consultation Page 2 of 64 Table of Contents 1 THE CALL FOR CONSULTATION ........................................................................................................ -

Charles C Thomas Publisher Cable : " Thomas • Springfield'" Telephone: 544-7110 (Area Code 217)

CHARLES C THOMAS PUBLISHER CABLE : " THOMAS • SPRINGFIELD'" TELEPHONE: 544-7110 (AREA CODE 217) CHARLES C THOMAS BOOKS, MONOGRAPHS and JOURNALS in MEDICINE, N P THOMAS SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY and PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PA YNE E L THOMAS Reply to HOME OFFICE 301-327 EAST LAWRENCE AVENUE • SPRINGFIELD-ILLINOIS 62703 November 3, 1971 MLss Jeanette Oberle p Books and Series University Microfilms ^ A Xerox Company Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Dear Kiss Oberle; Thank you for your letter of September 29, concerning your request to reproduce copies of the book by Professor Irving Horowitz, PHILOSOPHY, SCIENCE AfilO SOCIOLOGY OF KfoOWIJEDGE. We do ow« the copyright to Professor Horowitz* book, however we prefer that the author also gives his approval when copy is reproduced. If Professor Horowitz expects to be paid a 1056 royalty directly from you, I can well understand your decision to cancel the agreement. I am writing to Professor Horowitz to let him know that in such agreements, you pay the royalty directly to us as the publisher and holder of the copyright. We then, of course, pay him a per cent of the royalty. I will ask Professor Horowitz to contact you directly if he will allow you to reproduce copies of the book on this basis. If you do not hear from him, you may wish to cancel our agree ment. With kindest regards. Sincerely, CHARLES C THOMAS, PUBLISHER Lawrence Bentley dvertising & Sales A HCXM BV fBANt LLOY0 Wfi : -NATC DISTRIBUTORS THROUGHOUT THE WORLD ALABAMA, BIRMINGHAM E. F. Mahady Companv COLUMBUS, Long's College Book Com BALBOA. Cathedral Book Comer Libreria Dino Rossi University of Alabama Medical MICHIGAN pany CANARY ISLANDS Libr. -

(As) Conflict: Reflections on the European Border Regime

www.ssoar.info Under control?: or border (as) conflict; reflections on the European border regime Kasparek, Bernd; Hess, Sabine Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kasparek, B., & Hess, S. (2017). Under control?: or border (as) conflict; reflections on the European border regime. Social Inclusion, 5(3), 58-68. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v5i3.1004 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2017, Volume 5, Issue 3, Pages 58–68 DOI: 10.17645/si.v5i3.1004 Article Under Control? Or Border (as) Conflict: Reflections on the European Border Regime Sabine Hess 1,* and Bernd Kasparek 2 1 Institute for Cultural Anthropology/European Ethnology, University of Göttingen, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 bordermonitoring.eu, 81671 Munich, Germany; E-Mail: [email protected] * Corresponding author Submitted: 30 April 2017 | Accepted: 10 August 2017 | Published: 19 September 2017 Abstract The migrations of 2015 have led to a temporary destabilization of the European border and migration regime. In this con- tribution, we trace the process of destabilization to its various origins, which we locate around the year 2011, and offer a preliminary assessment of the attempts at re-stabilization. We employ the notion of “border (as) conflict” to emphasize that crisis and exception lies at the very core of the European border and migration regime and its four main dimensions of externalization, techno-scientific borders, an internal mobility regime for asylum seekers, and humanitarization. -

Running Into the Sand? the EU's Faltering Response to the Arab

December 2013 Running into the sand? The EU’s faltering response to the Arab revolutions By Edward Burke Running into the sand? The EU’s faltering response to the Arab revolutions By Edward Burke Before the Arab Spring, the EU believed it could promote political reform through economic liberalisation. That approach proved ineffective. Since the Arab Spring, the EU’s response has produced limited results. Its ‘more for more’ principle has not resulted in meaningful democratic change. European funds are stretched, North African agricultural exports remain unwelcome in Europe and security concerns often trump concern for democracy. A pragmatic approach to reform in the southern neighbourhood is needed, so that the EU takes account of the different circumstances in each of the countries. The EU should invest in civil service reform, education, judicial reform, a regional free-trade agreement and building security relations across the region. The EU should also increase its democracy assistance to the region through training and capacity- building. But, if it wants to remain a credible actor, Brussels should only fund democracy promotion in those countries where reforms are happening. 1. Introduction1 In 2011, the EU responded to the political uprisings Two years later, optimism for the region’s future has given that swept across North Africa and the Middle East way to concern and even despair. Most dramatically, with a striking mea culpa. In a speech to the European in July 2013 the Egyptian military overthrew a Parliament, the EU Commissioner for Enlargement and democratically-elected president, Mohammed Morsi. Even Neighbourhood Policy, Štefan Füle, admitted: “Too many in Tunisia, often regarded as the most ‘successful’ transition of us fell prey to the assumption that authoritarian in the region, a draft constitution threatens to severely regimes were a guarantee of stability in the region. -

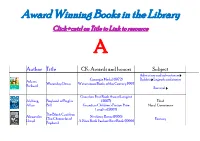

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+Cntrl on Title to Link to Resource A

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+cntrl on Title to Link to resource A Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Adventure and adventurers › Carnegie Medal (1972) Rabbits › Legends and stories Adams, Watership Down Waterstones Books of the Century 1997 Richard Survival › Guardian First Book Award Longlist Ahlberg, Boyhood of Buglar (2007) Thief Allan Bill Guardian Children's Fiction Prize Moral Conscience Longlist (2007) The Black Cauldron Alexander, Newbery Honor (1966) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1966) Prydain) Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject The Book of Three Alexander, A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1965) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd Prydain Book 1) A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1967) Alexander, Castle of Llyr Fantasy Lloyd Princesses › A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1968) Taran Wanderer (The Alexander, Fairy tales Chronicles of Lloyd Fantasy Prydain) Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2003) Whitbread (Children's Book, 2003) Boston Globe–Horn Book Award Almond, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 › The Fire-eaters (Fiction, 2004) David Great Britain › History Nestlé Smarties Book Prize (Gold Award, 9-11 years category, 2003) Whitbread Shortlist (Children's Book, Adventure and adventurers › Almond, 2000) Heaven Eyes Orphans › David Zilveren Zoen (2002) Runaway children › Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2000) Amateau, Chancey of the SIBA Book Award Nominee courage, Gigi Maury River Perseverance Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Angeli, Newbery Medal (1950) Great Britain › Fiction. › Edward III, Marguerite The Door in the Wall Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1961) 1327-1377 De A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1950) Physically handicapped › Armstrong, Newbery Honor (2006) Whittington Cats › Alan Newbery Honor (1939) Humorous stories Atwater, Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1958) Mr. -

Comisión Permanente De Liturgia Y Música, Subcomité De Revisión Del Libro De Oración Común

COMISIÓN PERMANENTE DE LITURGIA Y MÚSICA, SUBCOMITÉ DE REVISIÓN DEL LIBRO DE ORACIÓN COMÚN Miembros Rdo. Devon Anderson, Presidente Minnesota, VI 2018 Thomas Alexander Arkansas, VII 2018 Rvdmo. Thomas E. Breidenthal Ohio Sur, V 2018 Martha Burford Virginia, III 2018 Muy Rdo. Samuel G. Candler Atlanta, IV 2018 Drew Nathaniel Keane Georgia, IV 2018 Rvdmo. Dorsey McConnell Pittsburgh, III 2018 Nancy Bryan, Enlace con Church Publishing 2018 Rdo. Justin P. Chapman, Otro Minnesota, VI 2018 Mandato La [resolución] 2015-A169 de la 78ª. Convención General de la Iglesia Episcopal dice: Se resuelve, con el acuerdo de la Cámara de Diputados, que la 78ª. Convención General encargue a la Comisión Permanente de Liturgia y Música (SCLM por su sigla en inglés) que prepare un plan para la completa revisión del actual Libro de Oración Común y presente ese plan a 79ª. Convención General; y además Se resuelve, que dicho plan de revisión utilice las riquezas de la diversidad litúrgica, cultural, racial, generacional, lingüística , sexual y étnica de nuestra Iglesia a fin de compartir un culto común; y además Se resuelve, que el plan de revisión tome en consideración el uso de las actuales tecnologías que brindan acceso a una amplia gama de materiales litúrgicos; y además Se resuelve, que la Convención General solicité al Comité Permanente Conjunto de Programa, Presupuesto y Finanzas que considere una asignación presupuestaria de $30.000 para la aplicación de esta resolución. Resumen de las actividades INTRODUCCIÓN La Resolución A169 de la 78ª. Convención General de la Iglesia Episcopal encargó a la Comisión Permanente de Liturgia y Música (SCLM) “que preparara un plan para la revisión del actual Libro de Oración Común y lo presentara a la 79ª. -

The Impact of the European Migration Crisis on the Rise of Far-Right Populism in Italy

The Impact of the European Migration Crisis on the Rise of Far-Right Populism in Italy By Giulia Belardo A thesis submitted for the Joint Master-degree Global Economic Governance and Public Affairs Rome, Berlin and Nice June 2019 Thesis Supervisor: Prof. Leonardo Morlino Thesis Reviewer: Prof. Milad Zarin-Nejadan “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.” The Child in America: Behavior problems and programs. W.I. Thomas and D.S. Thomas, 1928 1 Abstract The migration crisis that hit the European continent in 2015-16 has been a very hotly debated topic both within and outside of single country borders. The sheer amount of asylum seekers crossing the Mediterranean reaching Europe through land and sea, uncovered the precariousness of not only national policies regarding immigration but also in a more drastic way the insufficient regulations at EU level, and transformed itself into a full-fledged crisis when it couldn’t be controlled anymore. In some countries more than others this has created very deep unhappiness within the native societies, which was heavily exploited by xenophobic populist parties. The right-wing parties, typically anti- immigrant, were heavily supporting closed borders and expulsions, and often during this time put their immigration agenda in the forefront of their political programmes, in order to capitalize on people’s fears and issue salience. The case of Italy exemplifies how even years after the peak of the migration crisis, the topic of immigration was still given very high importance by individuals, and answering to this salience, the Lega, a right-wing populist party, headed by Matteo Salvini, was able to win over vast amounts of the general electorate, in addition to its already well established supporters in northern Italy. -

Ministry of Foreign Affairs

AAnnnnuuaall RReeppoorrtt 22001122 ˜˜ MMiinniissttrryy ooff FFoorreeiiggnn AAffffaaiirrss December 2013 CONTENTS ____________________________________________________________________________________ Page Ministry of Foreign Affairs Director General – Economic and European Affairs 1 External Relations and Mediterranean Affairs Directorate 18 Multilateral and Global Issues Directorate 27 Protocol and Consular Services Directorate 31 Information Management Unit 38 Department of Citizenship and Expatriate Affairs 40 Central Visa Unit 50 Financial Management Directorate 52 Annual Report 2012 ~ Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1 Director General – Economic and European Affairs In 2012, the Directorate General continued to implement the Ministry’s strategic objectives, with a special focus on European matters and bilateral relations with European countries. The Director General also accompanied the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs to the monthly Brussels meetings, as well as other meetings, when required. Development and Humanitarian assistance remained an important part of the work of the Directorate General in line with Malta’s development policy. Working in collaboration with several local NGOs, the Directorate General co-ordinated the financing of a number of projects aimed at ameliorating the everyday life of people living in underdeveloped areas across various countries. The Directorate General was also responsible for monitoring the implementation of United Nations Security Council mandated sanctions and EU restrictive measures, together with relevant entities members of the Sanctions Monitoring Board. In this regard, the crisis in Syria and the situations in Libya and Iran called for added focus in a constantly evolving scenario. Other work of the Directorate General focused on promoting Malta’s cultural diplomacy as well as its economic and trade interests in liaison with relevant Government entities in Malta as well as the Missions abroad. -

The Euroepan Union's Priorities for the Area of Migration and Asylum

The Euroepan Union’s priorities for the area of migration and asylum The year 2009 was marked by a context of international by Community rather than State funds, which will make its economic crisis, which has affected migratory flows into the EU financing easier.2 along with the member states’ perception of the phenomena. However, contradicting European-level policy in irregular The debates arising from these two areas, led by the Czech immigration, both Belgium and Italy were carrying out amnesty and Swedish Presidencies of the EU, revolve around the issue campaigns for illegal immigrants throughout 2009. In the case of how to combat irregular immigration, the contents of the of Belgium, immigrants had to demonstrate that they were new Stockholm Programme, the Lisbon Treaty and managing integrated into the community, for which they had to justify flows of refugees and petitioners for asylum. residence in the country for at least five years or having worked With a situation of rising unemployment figures in the EU member in it for at least two and a half years. In response to criticism states and increased demand on the social services, reducing of the amnesty, the government denied having carried out any irregular immigration was one of the priorities in 2009. Hence, “mass regularisation”. 3 In Italy, the amnesty was aimed at those June saw the approval of a Directive of the European Parliament immigrants employed in domestic service or caring for the aged and the Council of Europe prohibiting the contracting of illegally from at least 1 August 2009.4 It is therefore clear that there staying third-country nationals, which is to come into force on is persisting inconsistency among the member states in their 20 July 2011.1 This instrument establishes certain obligations management of illegal immigration. -

Growing up and Growing Older: Books for Young Readers

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Nursing Nursing 2020 Growing Up and Growing Older: Books for Young Readers Sandra L. McGuire Dr. Professor Emeritus, The University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nurspubs Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, and the Elementary Education Commons Recommended Citation McGuire, Sandra L. Dr., "Growing Up and Growing Older: Books for Young Readers" (2020). Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Nursing. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nurspubs/160 This Creative Written Work is brought to you for free and open access by the Nursing at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Nursing by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Growing Up and Growing Older 2020 1 Growing Up and Growing Older: Books for Young Readers© An Annotated Booklist of Literature to Promote Positive Aging (Preschool-Third Grade) Dr. Sandra L. McGuire Professor Emeritus University of Tennessee, Knoxville Director Kids Are Tomorrow’s Seniors (KATS) Growing Up and Growing Older 2020 2 About the Author: Dr. McGuire is an advocate for combating ageism and promoting positive aging. Positive aging encompasses attitudes, lifestyles, and activities that maximize the potentials of life’s later years and enhance quality of life. She has presented at conferences and published in journals including: Childhood Education, Journal of School Nursing, Educational Gerontology, Journal of Health Education, and Creative Education; books including: The Encyclopedia of Ageism and Violence, Neglect and the Elderly; and in the federal Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) system. -

Download Book (PDF)

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions Fédération Internationale des Associations de Bibliothécaires et des Bibliothèques Internationaler Verband der bibliothekarischen Vereine und Institutionen Международная Федерация Библиотечных Ассоциаций и Учреждений Federación Internacional de Asociaciones de Bibliotecarios y Bibliotecas About IFLA www.ifla.org IFLA (The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions) is the lead- ing international body representing the interests of library and information services and their users. It is the global voice of the library and information profession. IFLA provides information specialists throughout the world with a forum for exchanging ideas and promoting international cooperation, research, and development in all fields of library activity and information service. IFLA is one of the means through which libraries, information centres, and information professionals worldwide can formulate their goals, exert their influence as a group, protect their interests, and find solutions to global problems. IFLA’s aims, objectives, and professional programme can only be fulfilled with the co- operation and active involvement of its members and affiliates. Currently, over 1,700 associations, institutions and individuals, from widely divergent cultural backgrounds, are working together to further the goals of the Federation and to promote librarianship on a global level. Through its formal membership, IFLA directly or indirectly represents some 500,000 library and information professionals worldwide. IFLA pursues its aims through a variety of channels, including the publication of a major journal, as well as guidelines, reports and monographs on a wide range of topics. IFLA organizes workshops and seminars around the world to enhance professional practice and increase awareness of the growing importance of libraries in the digital age.