Download Book (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Del Libro Impreso Al Libro Digital, by Marie Lebert

Project Gutenberg's Del libro impreso al libro digital, by Marie Lebert This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org ** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below ** ** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. ** Title: Del libro impreso al libro digital Author: Marie Lebert Release Date: May 28, 2011 [EBook #34091] Language: Spanish Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DEL LIBRO IMPRESO AL LIBRO DIGITAL *** Produced by Al Haines DEL LIBRO IMPRESO AL LIBRO DIGITAL MARIE LEBERT NEF, Universidad de Toronto, 2010 Copyright © 2010 Marie Lebert. Todos los derechos reservados. --- Este libro está dedicado a todas las personas que han contestado a mis preguntas durante los últimos diez años en Europa, en las Américas, en África y en Asia. Gracias por el tiempo que me han dedicado, y por su amistad. --- El libro impreso tiene cinco siglos y medio de edad. El libro digital tiene ya 40 años. Hoy en día uno puede leer un libro en su ordenador, en su asistente personal (PDA), en su teléfono móvil, en su smartphone o en su tableta de lectura. Es el viaje "virtual" el que vamos a emprender en este libro, el que se ha basado en unas miles de horas de navegación en la web durante diez años y en una centena de entrevistas llevadas a cabo por el mundo entero. -

Charles C Thomas Publisher Cable : " Thomas • Springfield'" Telephone: 544-7110 (Area Code 217)

CHARLES C THOMAS PUBLISHER CABLE : " THOMAS • SPRINGFIELD'" TELEPHONE: 544-7110 (AREA CODE 217) CHARLES C THOMAS BOOKS, MONOGRAPHS and JOURNALS in MEDICINE, N P THOMAS SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY and PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PA YNE E L THOMAS Reply to HOME OFFICE 301-327 EAST LAWRENCE AVENUE • SPRINGFIELD-ILLINOIS 62703 November 3, 1971 MLss Jeanette Oberle p Books and Series University Microfilms ^ A Xerox Company Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Dear Kiss Oberle; Thank you for your letter of September 29, concerning your request to reproduce copies of the book by Professor Irving Horowitz, PHILOSOPHY, SCIENCE AfilO SOCIOLOGY OF KfoOWIJEDGE. We do ow« the copyright to Professor Horowitz* book, however we prefer that the author also gives his approval when copy is reproduced. If Professor Horowitz expects to be paid a 1056 royalty directly from you, I can well understand your decision to cancel the agreement. I am writing to Professor Horowitz to let him know that in such agreements, you pay the royalty directly to us as the publisher and holder of the copyright. We then, of course, pay him a per cent of the royalty. I will ask Professor Horowitz to contact you directly if he will allow you to reproduce copies of the book on this basis. If you do not hear from him, you may wish to cancel our agree ment. With kindest regards. Sincerely, CHARLES C THOMAS, PUBLISHER Lawrence Bentley dvertising & Sales A HCXM BV fBANt LLOY0 Wfi : -NATC DISTRIBUTORS THROUGHOUT THE WORLD ALABAMA, BIRMINGHAM E. F. Mahady Companv COLUMBUS, Long's College Book Com BALBOA. Cathedral Book Comer Libreria Dino Rossi University of Alabama Medical MICHIGAN pany CANARY ISLANDS Libr. -

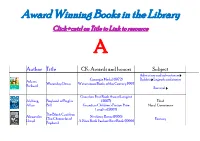

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+Cntrl on Title to Link to Resource A

Award Winning Books in the Library Click+cntrl on Title to Link to resource A Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Adventure and adventurers › Carnegie Medal (1972) Rabbits › Legends and stories Adams, Watership Down Waterstones Books of the Century 1997 Richard Survival › Guardian First Book Award Longlist Ahlberg, Boyhood of Buglar (2007) Thief Allan Bill Guardian Children's Fiction Prize Moral Conscience Longlist (2007) The Black Cauldron Alexander, Newbery Honor (1966) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1966) Prydain) Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject The Book of Three Alexander, A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1965) (The Chronicles of Fantasy Lloyd Prydain Book 1) A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1967) Alexander, Castle of Llyr Fantasy Lloyd Princesses › A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1968) Taran Wanderer (The Alexander, Fairy tales Chronicles of Lloyd Fantasy Prydain) Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2003) Whitbread (Children's Book, 2003) Boston Globe–Horn Book Award Almond, Cuban Missile Crisis, 1962 › The Fire-eaters (Fiction, 2004) David Great Britain › History Nestlé Smarties Book Prize (Gold Award, 9-11 years category, 2003) Whitbread Shortlist (Children's Book, Adventure and adventurers › Almond, 2000) Heaven Eyes Orphans › David Zilveren Zoen (2002) Runaway children › Carnegie Medal Shortlist (2000) Amateau, Chancey of the SIBA Book Award Nominee courage, Gigi Maury River Perseverance Author Title CK: Awards and honors Subject Angeli, Newbery Medal (1950) Great Britain › Fiction. › Edward III, Marguerite The Door in the Wall Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1961) 1327-1377 De A Horn Book Fanfare Best Book (1950) Physically handicapped › Armstrong, Newbery Honor (2006) Whittington Cats › Alan Newbery Honor (1939) Humorous stories Atwater, Lewis Carroll Shelf Award (1958) Mr. -

MANAGING BORDERS in an INCREASINGLY BORDERLESS WORLD Randall Hansen and Demetrios G

MANAGING BORDERS IN AN INCREASINGLY BORDERLESS WORLD Randall Hansen and Demetrios G. Papademetriou, Editors November 2013 © 2013 Migration Policy Institute All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. Permission for reproducing excerpts from this volume can be found at www.migrationpolicy.org/about/copy.php. Inquiries can also be directed to: Permissions Department, Migration Policy Institute, 1400 16th Street, NW, Suite 300, Washington, DC 20036, or by contacting [email protected]. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Managing borders in an increasingly borderless world / edited by Randall Hansen and Demetrios G. Papademetriou. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9831591-2-4 1. Border Security. 2. Boundaries. 3. Globalization. 4. Emigration and Immigration--Government policy. I. Hansen, Randall. II. Papademetriou, Demetrios G. HV6181.M36 2013 325--dc23 2013022842 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Managing borders in an increasingly borderless world / Randall Hansen and Demetrios G. Papademe- triou, editors. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9831591-2-4 (pbk.) 1. Border security--Case studies. I. Hansen, Randall, author, editor of compilation II. Papademetriou, Demetrios G., author, editor of compilation III. Migration Policy Institute, issuing body JV6225.M35 2013 320.1’2 C2013-905305-0 Cover Design: April Siruno, MPI Cover Photo: Modified version of “World Map” by Comstock images, via Photos.com, Image ID 78492474. Typesetting: Erin Perkins, LeafDev Suggested citation: Hansen, Randall and Demetrios G. Papademetriou, eds. -

Comisión Permanente De Liturgia Y Música, Subcomité De Revisión Del Libro De Oración Común

COMISIÓN PERMANENTE DE LITURGIA Y MÚSICA, SUBCOMITÉ DE REVISIÓN DEL LIBRO DE ORACIÓN COMÚN Miembros Rdo. Devon Anderson, Presidente Minnesota, VI 2018 Thomas Alexander Arkansas, VII 2018 Rvdmo. Thomas E. Breidenthal Ohio Sur, V 2018 Martha Burford Virginia, III 2018 Muy Rdo. Samuel G. Candler Atlanta, IV 2018 Drew Nathaniel Keane Georgia, IV 2018 Rvdmo. Dorsey McConnell Pittsburgh, III 2018 Nancy Bryan, Enlace con Church Publishing 2018 Rdo. Justin P. Chapman, Otro Minnesota, VI 2018 Mandato La [resolución] 2015-A169 de la 78ª. Convención General de la Iglesia Episcopal dice: Se resuelve, con el acuerdo de la Cámara de Diputados, que la 78ª. Convención General encargue a la Comisión Permanente de Liturgia y Música (SCLM por su sigla en inglés) que prepare un plan para la completa revisión del actual Libro de Oración Común y presente ese plan a 79ª. Convención General; y además Se resuelve, que dicho plan de revisión utilice las riquezas de la diversidad litúrgica, cultural, racial, generacional, lingüística , sexual y étnica de nuestra Iglesia a fin de compartir un culto común; y además Se resuelve, que el plan de revisión tome en consideración el uso de las actuales tecnologías que brindan acceso a una amplia gama de materiales litúrgicos; y además Se resuelve, que la Convención General solicité al Comité Permanente Conjunto de Programa, Presupuesto y Finanzas que considere una asignación presupuestaria de $30.000 para la aplicación de esta resolución. Resumen de las actividades INTRODUCCIÓN La Resolución A169 de la 78ª. Convención General de la Iglesia Episcopal encargó a la Comisión Permanente de Liturgia y Música (SCLM) “que preparara un plan para la revisión del actual Libro de Oración Común y lo presentara a la 79ª. -

Growing up and Growing Older: Books for Young Readers

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Nursing Nursing 2020 Growing Up and Growing Older: Books for Young Readers Sandra L. McGuire Dr. Professor Emeritus, The University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nurspubs Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, and the Elementary Education Commons Recommended Citation McGuire, Sandra L. Dr., "Growing Up and Growing Older: Books for Young Readers" (2020). Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Nursing. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nurspubs/160 This Creative Written Work is brought to you for free and open access by the Nursing at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Other Works -- Nursing by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Growing Up and Growing Older 2020 1 Growing Up and Growing Older: Books for Young Readers© An Annotated Booklist of Literature to Promote Positive Aging (Preschool-Third Grade) Dr. Sandra L. McGuire Professor Emeritus University of Tennessee, Knoxville Director Kids Are Tomorrow’s Seniors (KATS) Growing Up and Growing Older 2020 2 About the Author: Dr. McGuire is an advocate for combating ageism and promoting positive aging. Positive aging encompasses attitudes, lifestyles, and activities that maximize the potentials of life’s later years and enhance quality of life. She has presented at conferences and published in journals including: Childhood Education, Journal of School Nursing, Educational Gerontology, Journal of Health Education, and Creative Education; books including: The Encyclopedia of Ageism and Violence, Neglect and the Elderly; and in the federal Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) system. -

The 52 California Book Fair

The 52nd California book fair STAND 815 Item 127 BLACKWELL’S RARE BOOKS 48-51 Broad Street, Oxford, OX1 3BQ, UK Tel.: +44 (0)1865 333555 Fax: +44 (0)1865 794143 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @blackwellrare blackwell.co.uk/rarebooks BLACKWELL’S RARE BOOKS 1. Achebe (Chinua) Things Fall Apart. Heinemann, 1958, UNCORRECTED PROOF COPY FOR FIRST EDITION, a couple of handling marks and a few faint spots occasionally, a couple of passages marked lightly in pencil to the margin, pp. [viii], 185, crown 8vo, original tan wrappers printed to front and backstrip, the front with publication date and price written in blue ink, the stamp of ‘Juta & Co Ltd’ in Cape Town and ‘21 Apr 1958’ (date of sending?) stamped at foot, a few spots to edges, pencilled ownership inscription to half- title (flyleaf not called for), proof dustjacket chipped at head of backstrip panel with spotting to rear panel and rubbing to extremities, Juta & Co stamp at foot of front flap, good $3,900 An important work of post-colonial fiction, set in Nigeria at the end of the nineteenth-century - a scarce proof, the dustjacket of which does not carry the price but otherwise matches the design of the published version. A copy with African provenance, the publisher having offices in Cape Town. 2. (Alembic Press.) RICHARDSON (Maureen) Plant Papers’ Paper Plants. Kennington, Oxford, Alembic Press, 1989, FIRST EDITION, 25/25 COPIES (from an edition of 145 copies) printed on a special making of Japanese handmade Kozo paper, 4 linocuts by John Gibbs printed in brown, 14 tipped-in samples of plant paper (enumerated below) made by Maureen Richardson, this special edition with five additional paper samples (one printed with a John Gibbs linocut), pp. -

Martine Brand's Books Worldwide Distribution

Where to find COLLECTIONS BY MARTINE BRAND AUSTRIA City ZIP Code Store Address Feldkirchen in Kärnten 9560 Breschan GmbH Papier Kirchgasse 6 Gmunden 4810 Frick GmbH Wilhelm Theatergasse 11 Graz 8010 Morawa Buch&Med.GmbH&Co Am Eisernen Tor 1 Graz 8010 Bücher-Box Weiß Dr.Klaus Goethestraße 42 Graz 8010 T T Zinzendorfgasse 24 Graz 8020 Schmelzer Bettenhausen Hauptbahnhof Kassenhalle Graz-Seiersberg 8055 Morawa Buch&Med.GmbH&Co SC Seiersberg 5-Top2/2/12 Innsbruck 6020 T T Amraser-See-Straße 56a Innsbruck 6020 Thalia Buch & Medien GmbH Fil.68200 Museumstraße 4 Klagenfurt 9020 Morawa Buch&Med.GmbH&Co Wiesbadener Straße 5 Linz 4020 Schmelzer Bettenhausen Hauptbahnhof Linz 4020 Thalia Buch & Medien GmbH Fil.65100 Landstraße 41 Linz 4020 AIDA PresseInt. Mozartstraße 7 Linz 4040 Thalia Buch & Medien GmbH Fil.66500 Altenbergerstraße 69 Salzburg 5020 Morawa Buch&Med.GmbH&Co Alpenstraße 107/SCA Salzburg 5020 Schmelzer Bettenhausen Bahnhof Salzburg 5020 Morawa Buch&Med.GmbH&Co Europastraße 1 Salzburg 5020 Thalia Buch & Medien GmbH Fil.67300 Europastraße 1 Schrems 3943 T T Budweiserstraße 3 A Steyr 4400 Thalia Buch & Medien GmbH Fil.65200 Stadtplatz 2 Velden am Wörther See 9220 T T See Corso 4 Vienna 1010 Lasser Roswitha Kärntnerstraße 2 Vienna 1010 Morawa Buch&Med.GmbH&Co Wollzeile 11 Vienna 1030 Thalia Buch & Medien GmbH Fil.67500 Landstraßer Hauptstr.2a Vienna 1090 Schmelzer Bettenhausen Franz Josef Bahnhof Vienna 1300 Schmelzer Bettenhausen Airport Arrival Vienna 1300 Schmelzer Bettenhausen Airport Departure Wels 4600 Thalia Buch & Medien GmbH Fil.65400 Schmidtgasse 27 Wörgl 6300 T T Salzburger Straße 4 Where to find COLLECTIONS BY MARTINE BRAND BELGIUM City Store Street Antwerpen Relay Antw. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Japanese in multiracial Peru, 1899-1942 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4222t703 Author Moore, Stephanie Carol Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Japanese in Multiracial Peru, 1899-1942 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Stephanie Carol Moore Committee in charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Chair Professor Michael Monteon Professor Nayan Shah Professor Eric Van Young Professor Lisa Yoneyama 2009 Copyright Stephanie Carol Moore, 2009 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Stephanie Carol Moore is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ __________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page .……………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents .…………………………………………………………………… iv List of Figures ………………………………………………………………………... v List of Tables ……………………………………………………………………....... vi Map …………………………………………………………………………………. vii Acknowledgements …………………………………………………………………viii Vita …………………………………………………………………………………... xi Abstract …………………………………………………………………………….. -

Ebook Sales Channels

eBook sales channels Shop Name Core business Core Markets Shop URL International Amazon Kindle-Shop E-Shop worldwide (all www.amazon.de Amazon marketplaces) Apple Books E-Shop worldwide (55 www.apple.com countries) Barnes & Noble E-Shop US, worldwide www.barnesandnoble.com Google Play Store E-Shop worldwide play.google.com Kobo E-Shop worldwide (all www.kobo.com Kobo marketplaces) Bibliotheca Library US, ES EBSCO Library worldwide ebsco.com Overdrive Library US, GB www.overdrive.com ProQuest (Schweitzer Library worldwide www.proquest.com Fachinformationen) Storytel Flat Subscription worldwide Service (Streaming) Spanish-speaking countries Agapea E-Shop ES www.agapea.com BajaLibros E-Shop AR, LATAM www.bajalibros.com Casa del Libro E-Shop ES www.casadellibro.com Distribuidora Liverpool E-Shop MX www.liverpool.com.mx Educal E-Shop MX www.educal.com.mx El Corte Inglés E-Shop ES ocio.elcorteingles.es Gandhi E-Shop MX, US ghandi.com.mx La Central E-Shop ES www.lacentral.com Libreria Nacional E-Shop CO www.librerianacional.com Libreria Porrúa E-Shop MX www.porrua.mx Librería de la U E-Shop CO, MX www.libreriadelau.com Librería El Sótano E-Shop MX www.elsotano.com Librería Siglo del Hombre E-Shop LATAM libreriasiglo.com Librería Universia E-Shop CO libreria.universia.net.co Literato E-Shop NI www.literato.com.ni Perú eBooks E-Shop PE www.peruebooks.com Terra Networks México E-Shop MX Bookwire sales channels – Date: 02.06.2020 – © 2020 Bookwire GmbH Page 1 Shop Name Core business Core Markets Shop URL Odilo Library ES, LATAM, US Cegal Wholesaler -

Anthropology at Borders: Power, Culture, Memories

Anthropology at Borders: Power, Culture, Memories Barbora Spalová, Jakub Grygar (Eds.) Anthropology at Borders: Power, Culture, Memories Barbora Spalová, Jakub Grygar (Eds.) Anthropology at Borders: Power, Culture, Memories Editors: Barbora Spalová Department of Sociology, Charles University Department of Religious studies, University of Pardubice Jakub Grygar Department of Sociology, Charles University Department of Sociology, Masaryk University Peer- review: Fiona Magowan, Josef Kandert, Peter Vermeersch key words: anthropology; borders; power; culture; social memory Layout and graphics: Ondřej Pospíšil Proofreading: Jan Synek, Benjamin Cope Cover: Photographs were taken at PL-UA border crossing in Hrebenne (title page) and in Medyka (back page) by Marek Čaněk and Iva Voldánová. © 2006 Multicultural Center Prague, www.mkc.cz Th is publication and its individual contributions may be cited or briefl y quoted in line with the usual academic conventions. It can be downloaded for your own personal use but it must not be published elsewhere without the authors’ explicit permission. Th e publication cannot be used for commercial purposes or gain in any way. Conventions of academic citation should be observed similar to the following example: Bauer, P. (2006). Revisiting Territorial Memories in North Bohemian Borderlands. In Anthropology at Borders: Power, Culture, Memories ed. by Barbora Spalová and Jakub Grygar. Praha: FHS UK a MKC Prague, published at www.migrationonline.cz. ISBN 80-239-8391-1 Contents Acknowledgments......................................................................................................... -

Este Libro Forma Parte Del Acervo De La

Este libro forma parte del acervo de la Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM www.juridicas.unam.mx www.bibliojuridica.org LEGAL CULTURE AND LEGAL TRANSPLANTS THE SCOTTISH NATIONAL REPORT Esin ÖRÜCÜ Introduction. I. The Scottish Legal System. 1. Historical Perspectives. 2. Post- modernist Perspective. II. Specific Institutions or Legal Mechanisms. III. Conclusions. INTRODUCTION Of the two perspectives to be considered - as suggested by the General Rapporteur for this topic - Scotland can best be viewed as a predominantly receiving country rather than a country of origin. As a result of its historical development, which will be covered by this report, it can also be referred to as a classical and simple mixed jurisdiction.1 It is worth mentioning at the outset that the Scottish mix was not the result of the imposition of Common Law upon a Civilian system by a colonial power, this being the classical case in the birth of mixed jurisdictions such as South Africa, Louisiana, Quebec or Sri Lanka. It was born rather from close cultural and political ties with the jurisdictions from both traditions at different stages of its history, to be seen below.2 It is also usually claimed that the Scottish jurists created the mix by choosing the best of the ingredients from the various sources.3 The Scottish legal system is classified by our General Rapporteur as belonging to “the Roman-Common Law legal system, which includes 15 jurisdictions and 243 million inhabitants, representing almost 4.5% of Professor Emerita of Comparative Law, and Senior Honorary Research Fellow, University of Glasgow, P.h.D.