Copies, Clones, and Genre Building: Discourses on Imitation and Innovation in Digital Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

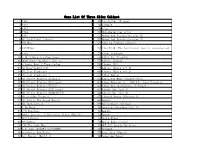

2475 in 1 Game List

Game List Of Three Sides Cabinet 1 1941 47 Air Gallet (Taiwan) 2 1942 48 Airwolf 3 1943 49 Ajax 4 1944 50 Akkanbeder(ver 2.5j) 5 1945 51 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version N) 6 10 Yard Fight (Japan) 52 Akuma-Jou Dracula(version P) 7 1943kai 53 Ales no Tsubasa (Japan) 8 1945Plus 54 Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars (set 2, unprotected) 9 19xx 55 Alien Syndrome 10 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge 56 Alien vs. Predator 11 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 57 Aliens (Japan) 12 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex 58 Aliens (US) 13 3D_Beastorizer(US) 59 Aliens (World set 1) 14 3D_Star Gladiator 60 Aliens (World set 2) 15 3D_Star Gladiator 2 61 Alley Master 16 3D_Street Fighter EX(Asia) 62 Alligator Hunt (unprotected) 17 3D_Street Fighter EX(Japan) 63 Alpha Mission II / ASO II - Last Guardian 18 3D_Street Fighter EX(US) 64 Alpha One (prototype, 3 lives) 19 3D_Street Fighter EX2(Japan) 65 Alpine Ski (set 1) 20 3D_Street Fighter EX2PLUS(US) 66 Alpine Ski (set 2) 21 3D_Strider Hiryu 2 67 Altered Beast (Version 1) 22 3D_Tetris The Grand Master 68 Ambush 23 3D_Toshinden 2 69 Ameisenbaer (German) 24 4 En Raya 70 American Speedway (set 1) 25 4-D Warriors 71 Amidar 26 64th. Street - A Detective Story (World) 72 Amigo 27 800 Fathoms 73 Andro Dunos 28 88 Games! 74 Angel Kids (Japan) 29 '99 The Last War 75 APB-All Points Bulletin 30 A.B. Cop (FD1094 317-0169b) 76 Appoooh 31 Acrobatic Dog_Fight 77 Aqua Jack (World) 32 Act-Fancer (World 1) 78 Aquarium(Japan) 33 Act-Fancer (World 2) 79 Arabian Act-Fancer Cybernetick Hyper Weapon (Japan 34 80 Arabian (Atari) revision 1) 35 Action Fighter 81 Arabian -

Studio Showcase

Contacts: Holly Rockwood Tricia Gugler EA Corporate Communications EA Investor Relations 650-628-7323 650-628-7327 [email protected] [email protected] EA SPOTLIGHTS SLATE OF NEW TITLES AND INITIATIVES AT ANNUAL SUMMER SHOWCASE EVENT REDWOOD CITY, Calif., August 14, 2008 -- Following an award-winning presence at E3 in July, Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ: ERTS) today unveiled new games that will entertain the core and reach for more, scheduled to launch this holiday and in 2009. The new games presented on stage at a press conference during EA’s annual Studio Showcase include The Godfather® II, Need for Speed™ Undercover, SCRABBLE on the iPhone™ featuring WiFi play capability, and a brand new property, Henry Hatsworth in the Puzzling Adventure. EA Partners also announced publishing agreements with two of the world’s most creative independent studios, Epic Games and Grasshopper Manufacture. “Today’s event is a key inflection point that shows the industry the breadth and depth of EA’s portfolio,” said Jeff Karp, Senior Vice President and General Manager of North American Publishing for Electronic Arts. “We continue to raise the bar with each opportunity to show new titles throughout the summer and fall line up of global industry events. It’s been exciting to see consumer and critical reaction to our expansive slate, and we look forward to receiving feedback with the debut of today’s new titles.” The new titles and relationships unveiled on stage at today’s Studio Showcase press conference include: • Need for Speed Undercover – Need for Speed Undercover takes the franchise back to its roots and re-introduces break-neck cop chases, the world’s hottest cars and spectacular highway battles. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Games Catalogue

GAMES CATALOGUE This book contains reviews of serious and commercial games that can be used for learning. www.projectgreat.eu 1 ABOUT GREAT = Game-based Research in Education and Action Training “We talk about creative learning. However, all learning involves some form of destruction, some form of creation and/or particular co-creation... The centrality of learning is here translated into a need for action: learning. Learn to create, learn how to create disruptions, learning to create innovation, learning to live together to collaborate. But if Learning and Technology, together, can build and host its core in the destructive potential of creativity and, by extension, of the collaboration, the need for meaning in all this is imperative. It is crucial to making sense of all forms of learning: informal, formal, not formal.” Roberto Carneiro in CREDITS Conference Book Creative Learning & Innovation:2009 Editor: Prof. DI Dr. Maja Pivec This project aims to proceed according to the Theory and Trends that cross Europe for its Layout: DI(FH) Anika Kronberger number one Priority in the EU 2020: Growth based on knowledge and innovation: Innovation; Contributors: APG - Portuguese Association of Human Resources Managers, FH JOANNEUM Education; Digital Society. University of Applied Sciences, Graz, Austria; MERIG - Multidisziplinares Institut fur Europa- Forschung Graz; AIF - Associazone Italiana Formatori; Gazy University, na Turquia; I.Zone The starting point for this project is the experience and knowledge base sustained by the Knowledge Systems partnership. Partners are well known and experienced. Games in Education are one of the Trends for the Future of Learning (JRC/IPTS. Trends for 2030). -

Threes!, Fives, 1024!, and 2048 Are Hard

Threes!, Fives, 1024!, and 2048 are Hard Stefan Langerman⋆1 and Yushi Uno2 1 D´epartement d’informatique, Universit´eLibre de Bruxelles, ULB CP 212, avenue F.D. Roosevelt 50, 1050 Bruxelles, Belgium. [email protected] 2 Department of Mathematics and Information Sciences, Graduate School of Science, Osaka Prefecture University, 1-1 Gakuen-cho, Naka-ku, Sakai 599-8531, Japan. [email protected] Abstract. We analyze the computational complexity of the popular computer games Threes!, 1024!, 2048 and many of their variants. For most known versions expanded to an m × n board, we show that it is NP-hard to decide whether a given starting position can be played to reach a specific (constant) tile value. 1 Introduction Fig. 2. The game 2048: a board Fig. 3. A forbidden (game over) and one of its initial configuration. Fig. 1. Threes! configuration. arXiv:1505.04274v1 [cs.CC] 16 May 2015 Threes! [2] is a popular puzzle game created by Asher Vollmer, Greg Wohlwend, and Jimmy Hinson (music), and released by Sirvo for iOS on January 23, 2014. The game received considerable attention from players, game critics and game designers. Only a few weeks after its release, an Android clone Fives appeared, and then an iOS clone 1024! with slightly modified rules. Shortly after, two open source web game versions, both called 2048 were released on github on the same day, one by Saming [12], the other by Gabriele Cirulli [5]. Since then over a hundred new variant have been catalogued [9]. In December 2014, Threes! received the Apple Game of the Year and the Apple Design award. -

Knockoffs, the Nemesis of the Gaming World by Jennifer Lloyd Kelly and Theis Finlev

Knockoffs, the Nemesis of the Gaming World by jennifer lloyd kelly and theis finlev On March 22, Amazon launched the Appstore, Championship did not infringe Karate Champ). These bringing video games to the fingertips of thousands of holdings are rooted in the fundamental principle of Android users who, like their iPhone and iPad-toting copyright law that one can receive protection only friends, can now purchase and play video games for the expression of an idea, not the idea itself. anywhere, anytime. Due to mobile device games’ Under this principle, certain elements of a work are ease of access, highly addictive nature, and low price free for the taking and, hence, cannot form the basis points, the market for such games has exploded in of an infringement claim. These elements include recent years. With many such games achieving almost general plots, themes and genres; scenes-à-faire cult-like status (think Angry Birds, which has achieved (common story elements); and purely functional over 100 million downloads across all platforms), the aspects of the work. In the context of sports or real- emergence of knockoffs is practically inevitable. life-themed video games, courts have concluded that content such as scoring systems, stereotypical In fact, we have already witnessed a number of characters, or common sports moves fall within these copyright disputes between game developers and unprotectable categories. See Capcom U.S.A. Inc. v. their alleged infringers, some of which have actually Data East Corp. 1994 WL 1751482 (N.D. Cal. 1994). reached litigation. However, before attorneys rush Because those games often are comprised largely to advise their mobile game developer clients to file of such content, they historically have received little suit, they should bear in mind the relatively limited protection under the copyright laws. -

Data-Dating-Galeriecharlot-F6kb87.Pdf

Curator Valentina Peri Data Dating 18.05 - 25.07.2018 Galerie Charlot 47, rue Charlot 75003 Paris, France Curator Valentina Peri Production Valérie Hasson-Benillouche Galerie Charlot - Paris/Tel Aviv galeriecharlot.com Graphic design Valentina Peri Rayane Ferrahi Editor Galerie Charlot Editions Data Dating What does it mean to love in the Internet age? How are digital interfaces reshaping our personal relationships? What do new technologies imply for the future of the romantic sphere? How do screens affect our sexual intimacy? Are the new means of connection shifting the old paradigms of adult life? The advent of the Internet and smartphones has brought about a split in the romantic lives of millions of people, who now inhabit both the real world and their very own “phone world”. In terms of romance and sexual intimacy these phenomena have generated new complexities that we are still trying to figure out. By bringing together the work of several international artists, the exhibition Data Dating attempts to explore new directions in modern romance: new forms of intimate communication, the process of commodification of love through online dating services and hookup applications, unprecedented meeting and mating behaviors, the renegotiation of sexual identities, and changing erotic mores and taboos. Over the past century, the history of dating practices has shown that the acquisition of new freedoms is often accompanied by suspicions and stereotypes: what appears disturbing to one generation often ends up being acceptable for the next. From the early computers algorithms of the 1960s, to the video cameras of the 1970s, the bulletin board systems of the 1980s, the Internet of the 1990s, and the smartphones of the last decade, every new format of electronically mediated matching has faced a stigma of some kind. -

Mobile Gaming 2012 CASUAL GAMES SECTOR REPORT What Are Mobile Games?

Mobile Gaming 2012 CASUAL GAMES SECTOR REPORT What are mobile games? Games that run on a mobile device such as a mobile phone, smartphone or What makes mobile games special? 1. Mobile games can integrate GPS, camera, microphone, position tablet computer. sensors and video. 2. Mobile devices are always on Devices such as iPhone, and always within arms reach. 3. Potential audience is enormous with nearly one mobile device Playbook, Galaxy Tab, per person. Windows Phone and Android devices. Keep in mind smartphone penetration Smartphones don’t rule the world… Global 15% MOBILE yet. As smartphone penetration feature phone penetration GAMES increases, so will the potential Global 85% audience for high value games. smartphone penetration China (urban) 35% smartphone penetration U.S. 31% smartphone penetration Russia 25% smartphone penetration India (urban) 23% smartphone penetration Turkey 14% source: ourmobileplanet.com Device Fragmentation Lots of different phones, means varying gaming capabilities, operating systems, processing power, screen sizes and graphics. IPHONE 4S XIAOMI M1 3.5” screen 4” screen OS: iOS 5 OS: Andriod OS 2.3 KINDLE FIRE 7” screen OS: Andriod OS 2.3 SAMSUNG WAVE Y NOKIA 3.2” screen 3.2” screen OS: Bada 2.0 OS OS: Symbian Belle iOS dominates mobile gaming Revenue by smartphone OS but Android will claim the top iOS 50% spot in the near future as Android 30% developers embrace Android and others 20% Google continues to iron out its payment process. Mobile Gaming Report 2012 CASUAL GAMES ASSOCIATION The Players mobile social games - avg. player mobile games - avg. player Female Male ages 25-34 ages 25-34 USA eCPM = $12.92 USA eCPM = $7.80 eCPM source Flurry eCPM source Flurry mobile gaming audience - size and projections (millions) Russia Brazil 250 U.S. -

Advanced Level Scoring - Scoring Points

® 2-4 players Age 6+ ADVANCED LEVEL SCORING - SCORING POINTS In both GAME 1: SPEED & GAME 2: COUNTDOWN, there are three ways of SCORING POINTS: 1. Playing a Tetrimino which lands touching one (or more) of the same colour, scores 1 push of the “+” button for each horizontal or vertical “touch point” ( ) connection made. Play then passes to the other player. 4 touch points created. Score = 4 pushes of the “+” button 2. Playing a Tetrimino which completes a full row (or rows) across the Matrix in any combination of colours, scores 3 pushes of the “+” button for each row created. The player is awarded another turn. 2 rows created. Score = 6 pushes of the “+” button 3. Playing a Tetrimino which lands touching one (or more) of the same colour AND completes a full row (or rows) across the Matrix in any combination of colours, scores 1 push of the “+” button for each horizontal or vertical “touch point” connection made and 3 pushes of the “+” button for each row created. The player is awarded another turn. 1 row and 5 touch points created. Score = 8 pushes of the “+” button NOTE: Each time a full row is created, make sure to slide the Row Indicator to the top of that row to help remember the position of the last full completed row. ADVANCED LEVEL SCORING - LOSING POINTS In the advanced game, LOSING POINTS are played exactly as the standard rules. 1. For playing a Tetrimino which lands leaving an unfillable hole(s) below it ( ), the player must press the “-“ button 1 time for EACH hole created. -

Beginning Android Games SECOND EDITION Mario Zechner | Robert Green

Build Android smartphone and tablet game apps Beginning Android Games SECOND EDITION Mario Zechner | Robert Green www.finebook.ir For your convenience Apress has placed some of the front matter material after the index. Please use the Bookmarks and Contents at a Glance links to access them. www.finebook.ir Contents at a Glance About the Authors ........................................................................................................ xix About the Technical Reviewer ..................................................................................... xxi Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................... xxiii Introduction ................................................................................................................ xxv ■■Chapter 1: An Android in Every Home..........................................................................1 ■■Chapter 2: First Steps with the Android SDK..............................................................21 ■■Chapter 3: Game Development 101............................................................................55 ■■Chapter 4: Android for Game Developers.................................................................107 ■■Chapter 5: An Android Game Development Framework...........................................193 ■■Chapter 6: Mr. Nom Invades Android........................................................................237 ■■Chapter 7: OpenGL ES: A Gentle Introduction...........................................................275 -

Downloadable Tetris Game Free Tetris Download

downloadable tetris game free Tetris Download. Types of the game are listed from the simplest to the hardest. Even small kids can play in the Simple Tetris mode, but playing Mutatix and Crazy is for extreme Tetris players in general. You will find friendly interface, nice sounds, music, large High scores table and World Records Table in this Tetris game. Also before writing your name to High Scores you can choose a pleased face from the list of more than 200 funny faces. The goal of the Tetris game is to maximize your score by placing the falling blocks or triangles into lines. Every assembled line that has disappeared increases your score. If you are a Tetris fan, you should download Crazy Tetris game! Free download Tetris and enjoy playing it for hours and even days! Tetris is a really good game for having some rest after work! Tetris Download. Do you want to play Crazy Tetris? Here you can free download Tetris for Windows. To download this action puzzle game click on the link below: Supported Tetris Languages. Crazy Tetris game has multilingual interface. Supported Languages: Bulgarian, Catalan, Chinese, Dutch, English, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Portuguese (Brazilian), Russian, Spanish, Swedish, Ukrainian. Pentium 166 or better Operating system: Windows 95/98/Me/NT4/2000/XP/Vista/7/8/8.1/10 Video card with high color mode. Distribution. The SHAREWARE version of the Crazy Tetris is free distributed. You may free download and use the SHAREWARE version free of charge for 30 days. If after 30 days you would like to continue using Crazy Tetris game, then you should register Tetris. -

Catalogo Nintendo Switch

Inverno 2020/2021 OMAGGIO Che cos'è Nintendo Switch? Nintendo Switch è una console per giocare dove, quando e con chi vuoi La famiglia Nintendo Switch comprende due console Nintendo Switch – pensata per giocare a casa oppure dove vuoi Tre modi di giocare Modalità TV Modalità da tavolo Modalità portatile p.06 ~ p.09 Nintendo Switch Lite pensata per giocare in mobilità p.10 ~ p.11 Dove, quando e con chi vuoi. Tre modalità 1 Modalità TV Nintendo Switch consente tre modalità di gioco. Inserisci Nintendo Switch nella base e gioca in HD sulla tua TV. Collegarlo alla TV è facile La console si accende appena la rimuovi Adattatore AC dalla base. Porta la console con te e Nintendo Switch continua a giocare in modalità portatile. Cavo HDMI Basta collegare l'adattatore AC e il cavo HDMI inclusi nella confezione a ogni uscita. Dove, quando e con chi vuoi. Tre modalità 2 Usa lo stand integrato e condividi il divertimento Modalità da tavolo con un gioco multiplayer. Inserendo i due Joy-Con nell'impugnatura Joy-Con Joy-Con ottieni un controller tradizionale. Nintendo Switch dispone di Senza l'impugnatura, ogni Joy-Con è un controller due controller, uno per lato, che indipendente. funzionano anche insieme. Nintendo Switch consente tre modalità di gioco. Tre modalità 3 Collega i controller Joy-Con alla console e Modalità portatile gioca dove vuoi. Nintendo Switch Lite – Nintendo Switch Lite è una console compatta, leggera e con comandi integrati. pensata per giocare in mobilità Nintendo Switch Lite è compatibile con tutti i software per Nintendo Switch che possono essere giocati in modalità portatile.