Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

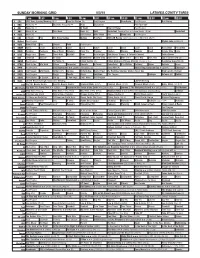

Sunday Morning Grid 5/3/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/3/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Equestrian PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Brooklyn Nets at Atlanta Hawks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Pre-Race NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Afghan Luke (2011) (R) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Fast. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Father Brown 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

The Pleasures of Verisimilitude in Biographical Fiction Films

As if Alive before Us: The Pleasures of Verisimilitude in Biographical Fiction Films Anneli Lehtisalo (University of Tampere) Introduction The biopic, or biographical fiction film, is characterised by the real or historical per- son as a protagonist (Custen 5; Taylor 22; Bingham, Whose Lives 8). Despite the acknowledged potential for artistic freedom in fiction film, this generic feature— the reference to the real world—informs the genre. Film-makers, reviewers and film scholars repeatedly ask, how truthful or verisimilar a portrayal, an actor or a performance is or how well a biographical film depicts a historical story. Tradition- ally, film-makers have defined “the degree of truth” of a film at its opening (Custen 51). A title card or a voice-over might assert that the film follows known facts. The declaration can serve as a disclaimer, where the audience is informed that a film is only inspired by real events or the story is only partly factual. Thus, it is possible to specify a biopic as fictional. In any case, some definition is expected. Contempo- rary newspaper criticism commonly estimates the truthfulness and verisimilitude of a film. If a film portrays a famous or respected public figure, the authenticity of the depiction will almost inevitable be debated. In addition, the truthfulness and verisimilitude of biopics are constantly discussed in scholarly criticism. George F. Custen, in his seminal book Bio/Pics: How Hollywood Constructed Public His- tory, devotes a whole chapter to the discussion of the relationship between a real person and a protagonist in a film (110–47). His aim is to illustrate how certain cir- cumstances of the film industry shaped the biopics of the studio era. -

From Free Cinema to British New Wave: a Story of Angry Young Men

SUPLEMENTO Ideas, I, 1 (2020) 51 From Free Cinema to British New Wave: A Story of Angry Young Men Diego Brodersen* Introduction In February 1956, a group of young film-makers premiered a programme of three documentary films at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank). Lorenza Mazzetti, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson thought at the time that “no film can be too personal”, and vehemently said so in their brief but potent manifesto about Free Cinema. Their documentaries were not only personal, but aimed to show the real working class people in Britain, blending the realistic with the poetic. Three of them would establish themselves as some of the most inventive and irreverent British filmmakers of the 60s, creating iconoclastic works –both in subject matter and in form– such as Saturday Day and Sunday Morning, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and If… Those were the first significant steps of a New British Cinema. They were the Big Screen’s angry young men. What is British cinema? In my opinion, it means many different things. National cinemas are much more than only one idea. I would like to begin this presentation with this question because there have been different genres and types of films in British cinema since the beginning. So, for example, there was a kind of cinema that was very successful, not only in Britain but also in America: the films of the British Empire, the films about the Empire abroad, set in faraway places like India or Egypt. Such films celebrated the glory of the British Empire when the British Empire was almost ending. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

NVS 12-1-13-Announcements-Page;

Announcements: CFPs, conference notices, & current & forthcoming projects and publications of interest to neo-Victorian scholars (compiled by the NVS Assistant Editors) ***** CFPs: Journals, Special Issues & Collections (Entries that are only listed, without full details, were highlighted in a previous issue of NVS. Entries are listed in order of abstract/submission deadlines.) Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic Edited Collection Abstracts due: 18 December 2020 Articles due: 30 April 2021 Famed for their scandalous content and supposed pernicious influence on a young readership, it is little wonder why the Victorian penny dreadful was derided by critics and, in many cases, censored or banned. These serialised texts, published between the 1830s until their eventual decline in the 1860s, were enormously popular, particularly with working-class readers. Neglecting these texts from Gothic literary criticism creates a vacuum of working-class Gothic texts which have, in many cases, cultural, literary and socio-political significance. This collection aims to redress this imbalance and critically assess these crucial works of literature. While some of these penny texts (i.e. String of Pearls, Mysteries of London, and Varney the Vampyre to name a few) are popularised and affiliated with the Gothic genre, many penny bloods and dreadfuls are obscured by these more notable texts. As well as these traditional pennys produced by such prolific authors as James Malcolm Rymer, Thomas Peckett Press, and George William MacArthur Reynolds, the objective of this collection is to bring the lesser-researched, and forgotten, texts from neglected authors into scholarly conversation with the Gothic tradition and their mainstream relations. This call for papers requests essays that explore these ephemeral and obscure texts in relevance to the Gothic mode and genre. -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study There Are

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study There are so many things that people can do to entertain themselves. One of them is watching a film. It is fun to watch a film. There are things that make films entertaining. Films have stories, supporting visual effects, and music score. The stories attract the viewers to enjoy a part of other character's life. The visual effects make the viewers be able to imagine that what they see is real. It looks like the events in the film really happened, while the music score intensifies the feeling that the film wants to deliver. The story is the most important part of the film. Without a good story, even if a film is started by some really great actors or actresses, the film will not be special. There are two ways or plot that a movie maker can use to deliver the story. The first way to deliver a story is a linear plot. The movie begins with the introduction of the characters. Everything seems normal. Then the problem appears and the movie finished when the characters can solve the problem. The second way is the flashback plot. In this plot, the story begins with the end. Then, a character tells the story from the beginning. All things that the movie viewers want to see are actually represented by the genre of the films. There are many things that people can see from a film, like funny things that can be seen from a comedy film, 1 thrilling action that can be seen from an action film, or even scary thing that can be seen from a horror film. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

9. List of Film Genres and Sub-Genres PDF HANDOUT

9. List of film genres and sub-genres PDF HANDOUT The following list of film genres and sub-genres has been adapted from “Film Sub-Genres Types (and Hybrids)” written by Tim Dirks29. Genre Film sub-genres types and hybrids Action or adventure • Action or Adventure Comedy • Literature/Folklore Adventure • Action/Adventure Drama Heroes • Alien Invasion • Martial Arts Action (Kung-Fu) • Animal • Man- or Woman-In-Peril • Biker • Man vs. Nature • Blaxploitation • Mountain • Blockbusters • Period Action Films • Buddy • Political Conspiracies, Thrillers • Buddy Cops (or Odd Couple) • Poliziotteschi (Italian) • Caper • Prison • Chase Films or Thrillers • Psychological Thriller • Comic-Book Action • Quest • Confined Space Action • Rape and Revenge Films • Conspiracy Thriller (Paranoid • Road Thriller) • Romantic Adventures • Cop Action • Sci-Fi Action/Adventure • Costume Adventures • Samurai • Crime Films • Sea Adventures • Desert Epics • Searches/Expeditions for Lost • Disaster or Doomsday Continents • Epic Adventure Films • Serialized films • Erotic Thrillers • Space Adventures • Escape • Sports—Action • Espionage • Spy • Exploitation (ie Nunsploitation, • Straight Action/Conflict Naziploitation • Super-Heroes • Family-oriented Adventure • Surfing or Surf Films • Fantasy Adventure • Survival • Futuristic • Swashbuckler • Girls With Guns • Sword and Sorcery (or “Sword and • Guy Films Sandal”) • Heist—Caper Films • (Action) Suspense Thrillers • Heroic Bloodshed Films • Techno-Thrillers • Historical Spectacles • Treasure Hunts • Hong Kong • Undercover