The Pleasures of Verisimilitude in Biographical Fiction Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fredrika Runeberg Och Smakdomarna Explicit Subjektivitet Och Värdering I Svensk Litteraturhistorieskrivning

MAGISTERUPPSATS I BIBLIOTEKS- OCH INFORMATIONSVETENSKAP VID BIBLIOTEKSHÖGSKOLAN/BIBLIOTEKS- OCH INFORMATIONSVETENSKAP 2001:34 Fredrika Runeberg och smakdomarna Explicit subjektivitet och värdering i svensk litteraturhistorieskrivning MARIE SKANTZE Svensk titel Smakdomarna och Fredrika Runeberg: explicit subjektivitet och värdering i svensk litteraturhistorieskrivning Engelsk titel The arbiters of taste and Fredrika Runeberg: explicit subjectivity and valuation in Swedish literary historiography Författare Marie Skantze Färdigställt 2001 Handledare Anders Frenander, kollegium 1 Abstract This essay is a study of explicit subjectivity and valuation in Swedish literary historiography from a power perspective. The methodology involves qualitative perusal of literary handbooks from 1915 to 1999. The author Fredrika Runeberg is taken as a window, in that I have examined if and how she is described in the selected handbooks. The main purpose has been to see if subjectivity in disparaging terms and condemnation of authorship have become more evident during the years under consideration. I have related the twelve selected handbooks to Hallberg´s five methods for literary historiography. This has been done to see if the degree of explicit subjectivity correlates to the method chosen. Professor of Literature Gunnar Hansson states that explicit subjectivity has become more extreme with increased space given descriptions in Swedish literary handbooks during recent years. The authors of the handbooks present their judgements as ”objective” and generalized facts. Fredrika Runeberg is mentioned in eleven of the twelve selected literary handbooks. She is mainly portrayed in relationship to her husband, the national poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg. In handbooks from the 1980s and onward the sociological method dominates. This means that interest in the social situation pertaining to Fredrika Runeberg´s authorship is shown by the increased space given to her presentation. -

Träanvändning Och Materialval I Finska Prästgårdar

Helsingin yliopisto - Helsingfors universitet - University of Helsinki Tiedekunta/Osasto - Fakultet/ Sektion - Faculty Laitos - Institution - Department Agrikultur-forstvetenskapliga fakulteten Institutionen för skogsvetenskaper Tekijä - Författare - Author Backström Harry Sanfrid Työn nimi - Arbetets titel - Title Materialval i prästgårdarna Oppiaine - Läroämne - Subject Träteknologi Työn laji/Arbetets art/Level Aika/Datum/Month and year Sivumäärä/Sidoantal/Number of pages Kandidatavhandling 07/2016 100 s. Tiivistelmä/Referat/Abstract Prästgårdar är en del av kulturmiljön och den byggnadshistoriska miljön i det finländska samhället. En stor del av prästgårdarna är innefattade i Museiverkets register över byggda kulturmiljöer av riksintresse, så kallade RKY-objekt. Vid byggandet av prästgårdar har man i stor utsträckning använt sig av trä som konstruktions-, inrednings och fasadmaterial, framför allt när det gäller äldre prästgårdar som byggdes på landsbygden. Undersökningen innehöll två huvudfrågeställningar: För det första har beskrivits de trä- och övriga konstruktioner som man ur generell och principiell synvinkel använde vid byggandet av prästgårdarna, hur detta virke anskaffades, vilka trädslagsval som gjordes, vilka kvalitetskrav som ställdes på konstruktionsvirket samt hur trävirket och konstruktionerna vidareförädlades. Undersökningen innehöll också fallstudier. Fallstudierna utgörs av 4 prästgårdar på Borgå stifts område. För fallstudieobjekten redogjordes för grund/ stenfot, bjälklagHELSINGFORS (bottenplatta), huskroppens UNIVERSI -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

NVS 12-1-13-Announcements-Page;

Announcements: CFPs, conference notices, & current & forthcoming projects and publications of interest to neo-Victorian scholars (compiled by the NVS Assistant Editors) ***** CFPs: Journals, Special Issues & Collections (Entries that are only listed, without full details, were highlighted in a previous issue of NVS. Entries are listed in order of abstract/submission deadlines.) Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic Edited Collection Abstracts due: 18 December 2020 Articles due: 30 April 2021 Famed for their scandalous content and supposed pernicious influence on a young readership, it is little wonder why the Victorian penny dreadful was derided by critics and, in many cases, censored or banned. These serialised texts, published between the 1830s until their eventual decline in the 1860s, were enormously popular, particularly with working-class readers. Neglecting these texts from Gothic literary criticism creates a vacuum of working-class Gothic texts which have, in many cases, cultural, literary and socio-political significance. This collection aims to redress this imbalance and critically assess these crucial works of literature. While some of these penny texts (i.e. String of Pearls, Mysteries of London, and Varney the Vampyre to name a few) are popularised and affiliated with the Gothic genre, many penny bloods and dreadfuls are obscured by these more notable texts. As well as these traditional pennys produced by such prolific authors as James Malcolm Rymer, Thomas Peckett Press, and George William MacArthur Reynolds, the objective of this collection is to bring the lesser-researched, and forgotten, texts from neglected authors into scholarly conversation with the Gothic tradition and their mainstream relations. This call for papers requests essays that explore these ephemeral and obscure texts in relevance to the Gothic mode and genre. -

1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study There Are

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study There are so many things that people can do to entertain themselves. One of them is watching a film. It is fun to watch a film. There are things that make films entertaining. Films have stories, supporting visual effects, and music score. The stories attract the viewers to enjoy a part of other character's life. The visual effects make the viewers be able to imagine that what they see is real. It looks like the events in the film really happened, while the music score intensifies the feeling that the film wants to deliver. The story is the most important part of the film. Without a good story, even if a film is started by some really great actors or actresses, the film will not be special. There are two ways or plot that a movie maker can use to deliver the story. The first way to deliver a story is a linear plot. The movie begins with the introduction of the characters. Everything seems normal. Then the problem appears and the movie finished when the characters can solve the problem. The second way is the flashback plot. In this plot, the story begins with the end. Then, a character tells the story from the beginning. All things that the movie viewers want to see are actually represented by the genre of the films. There are many things that people can see from a film, like funny things that can be seen from a comedy film, 1 thrilling action that can be seen from an action film, or even scary thing that can be seen from a horror film. -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries. -

Malayalam Biopics: from Books to Films

MALAYALAM BIOPICS: FROM BOOKS TO FILMS Gayatri Binu Registered Number: 1324032 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Communication Christ University Bengaluru 2015 Program Authorized to Offer Degree Department of Media Studies II Authorship Christ University Declaration Department of Media Studies This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a master’s thesis by Gayatri Binu Registered Number: 1324032 and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Committee Members: _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ Date: __________________________________ III IV I, Gayatri Binu, confirm that this dissertation and the work presented in it are original. 1. Where I have consulted the published work of others this is always clearly attributed. 2. Where I have quoted from the work of others the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations this dissertation is entirely my own work. 3. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. 4. If my research follows on from previous work or is part of a larger collaborative research project I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. 5. I am aware and accept the penalties associated with plagiarism. Date: V VI Abstract Malayalam Biopics: From Books to Films Gayatri Binu MS in Communication, Christ University, Bangalore This article talks about the difficulties that emerge when considering biographical films that are focused around biographical or autobiographical works of writing utilizing careful investigations of three Malayalam films. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 356 2nd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Ecological Studies (CESSES 2019) "National Writing" in the Biography Film of Contemporary Russian Characters Taking "Legend No.17" as an Example Na Ma Xi'an University Xi'an, China 710065 Abstract—For a long time, Russian film has been famous shaping and presentation of characters as the main content, for its profound historical background and grand and elegant with the characteristics of the development track and cultural taste in the national film of "The Belt and Road". In spiritual predicament of biographical characters being Russian films since the new century, due to authenticity and presented in narration, Russian biography films are more important advocacy role, character biographical film has likely to be based on the principles of socialist realistic become one of the representative types of films. This paper, creation, "describing the typical environment and shaping the taking "Legend No.17" as a cut-in text, analyzes how does typical characters according to real characters and real contemporary Russian film completes the task of exporting the event." (Encyclopedia of China Film Volume). The choice of mainstream ideology of culture through the construction of the biographical characters is insisted on the field of "public history" in the Film. "Outstanding figures in history and real life.", and takes their Keywords—biography film; Russian film; "Legend No.17" great achievements as an important selection criterion for typical events on the selection of the real event. The above Russian biographical films are characterized by highlighting I. -

Free Indirect Discourse in Early Finnish Novels by Fredrika Runeberg and Zacharias Topelius

AR T IC le S Mari Hatavara Free Indirect Discourse in Early Finnish Novels by Fredrika Runeberg and Zacharias Topelius [H]an såg med en namnlös känsla, den han aldrig förr erfarit, denna flicka från ett aflägset och bortglömdt land, om hvilket han knappt hade anat, att kärlek och skönhet äfven här kunde utöfva sin makt på menniskohjertat [- -]. (HaF, 210) He saw, with a nameless feeling that he had never before experienced, this girl from a faraway and forgotten land; he had hardly surmised that even here love and beauty could wield their power over the human heart. In the passage above Scottish Jacob Keith, a commander in the Russian Army during the war 1741−1743 between Russia and Sweden (Finland), has met a young Finnish lady by the name of Eva Merthen for the first time. The story of the two lovers is told in the first Finnish historical novel,Hertiginnan af Finland (“The Duchess of Finland”, 1850=HaF), alongside the events of the war and political history. The passage dem- onstrates a keen interest in depicting Jacob’s mind, his inner feelings and thoughts as he suddenly falls in love. It uses the narrative mode of free indirect discourse (=FID), which carries traces of the discourse both of the character and the third person narrator as it depicts a character’s thoughts or speech. As Brian McHale (2005, 189) concisely defines it, “FID is ‘indirect’ because it conforms in person and tense to the template of indirect discourse, but ‘free’ because it is not subordinated grammatically to a verb of saying or thinking.” The proximity to a character’s free discourse is marked by, for instance, the use of idiomatic language and deictic adverbs pointing to the character’s own here and now (McHale 1978, 264−273). -

Emotional and Social Ties in the Construction of Nationalism: a Group Biographical Approach to the Tengström Family in Nineteenth-Century Finland

Emotional and Social Ties in the Construction of Nationalism: A Group Biographical Approach to the Tengström Family in nineteenth-century Finland REETTA EIRANEN Tampere University Introduction Nations and nationalisms have typically been understood and approached in the framework of public sphere. The context of the private sphere has been regarded as apolitical, and hence irrelevant. This has contributed to an emphasis on male actors, who have been associated with the public, and to the exclusion of women, who have been connected with the private. Consequently, in many national histories, men are treated as actors, whereas women represent the nation’s tradition in a metaphorical and symbolic role. More often than not, conventional national historiography fails to take gender into account or to incorporate women’s experiences and activities. Nevertheless, interest in the relation between gender and nationalism has increased in recent decades.1 Moreover, emotions have traditionally been associated with the feminine and the private and seen as secondary to reason, which in part explains why emotions are often missing from the analysis of decision-making and Reetta Eiranen, ‘Emotional and Social Ties in the Constuction of Nationalism: A Group Biographical Approach to the Tengström Family in nineteenth-century Finland’ in: Studies on National Movements 4 (2019) Studies on National Movements 4 (2019) | Article actions. During the 2000s, the history of emotions has constituted a growing field in historical research. Emotions are, in a way, intrinsic to nationalism and belong to a nation’s ontology. They are part of the relation an individual has with the nation, and nations can even be seen as ‘emotional communities.’ In more general terms, the significance of emotions for politics has increasingly been recognized.2 In addition, the ‘emotion’ approach can be associated with an emphasis on the personal meanings of nationalism. -

A Study of Xu Xu's Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS

Allegories and Appropriations of the ―Ghost‖: A Study of Xu Xu‘s Ghost Love and Its Three Film Adaptations THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Qin Chen Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Master's Examination Committee: Kirk Denton, Advisor Patricia Sieber Copyright by Qin Chen 2010 Abstract This thesis is a comparative study of Xu Xu‘s (1908-1980) novella Ghost Love (1937) and three film adaptations made in 1941, 1956 and 1995. As one of the most popular writers during the Republican period, Xu Xu is famous for fiction characterized by a cosmopolitan atmosphere, exoticism, and recounting fantastic encounters. Ghost Love, his first well-known work, presents the traditional narrative of ―a man encountering a female ghost,‖ but also embodies serious psychological, philosophical, and even political meanings. The approach applied to this thesis is semiotic and focuses on how each text reflects the particular reality and ethos of its time. In other words, in analyzing how Xu‘s original text and the three film adaptations present the same ―ghost story,‖ as well as different allegories hidden behind their appropriations of the image of the ―ghost,‖ the thesis seeks to broaden our understanding of the history, society, and culture of some eventful periods in twentieth-century China—prewar Shanghai (Chapter 1), wartime Shanghai (Chapter 2), post-war Hong Kong (Chapter 3) and post-Mao mainland (Chapter 4). ii Dedication To my parents and my husband, Zhang Boying iii Acknowledgments This thesis owes a good deal to the DEALL teachers and mentors who have taught and helped me during the past two years at The Ohio State University, particularly my advisor, Dr. -

Raportti.Pdf

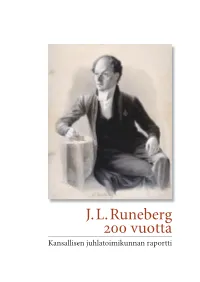

J. L. Runeberg 200 vuotta Kansallisen juhlatoimikunnan raportti Sisältö Kuvamme Runebergista on tullut eläväksi 3 Sanoin & kuvin & sävelin – Kansallinen juhlatoimikunta 4 Summa summarum – eli voiko saldosta puhua? 5 Humanismin perintö 9 J. L. Runeberg 200 sanoin & kuvin & sävelin 15 Julkaisujen juhlavuosi 25 Juhlavuoden tuotteita 28 Runebergin juhlintaa kautta maan 30 Runebergin jäljillä – Juhlatoimikunnan jäsenten osaraportteja 31 Runebergin jäljillä 32 Firandet av J. L. Runebergs 200-års jubileumsår i Jakobstad 33 Kommentarer över firandet av Runebergs jubileumsår i Pargas 36 J. L. Runebergin juhlavuosi Porvoossa 38 Runebergin juhlavuosi Ruovedellä 42 Pölyjä rintakuvista ja muistomerkeistä, Saarijärvi 46 Tapahtumia Saarijärvellä 2004 50 Turussa juhlittiin Runebergia sanoin, sävelin ja räpätenkin 54 Koululainen Runeberg Vaasassa 56 ”Runeberg 200 vuotta” -juhlavuoden tapahtumia Vaasassa 57 Ruotusotamies Bång ja Sven Dufva, SKS 59 Svenska litteratursällskapets Runebergsprojekt 2004 62 Litteet 68 1. Organisaatio/Organisation 69 2. Avustukset Runeberg-tapahtumille 71 3. Laulu liitää yli meren maan – J. L. Runeberg 200 vuotta Sången flyger över land och hav – J. L. Runeberg 200 år 75 4. Kirjoja ja julkaisuja / Böcker och publikationer 78 Julkaisija: Kansallinen J. L. Runebergin 200-vuotisjuhlatoimikunta Toimittaja: Sari Hilska Ulkoasu: Peter Sandberg Kannen kuva: J. L. Runeberg, Johan Knutson, 1848 www.runeberg.net 2 Per-Håkan Slotte Kuvamme Runebergista on tullut eläväksi Kansallinen J. L. Runebergin 200-vuotistoimikunta on saattanut työnsä pää- tökseen. Toivomukseni on, että tämä raportti antaa yleiskuvan sekä toimikunnan työstä että juhlavuoden ohjelmasta. Toimikunta vastasi juhlavuoden valtakunnalli- sesta markkinoinnista ja tapahtumien tukemisesta. Lisäksi se järjesti valtakunnallisen pääjuhlan Porvoossa helmikuun 5. päivänä 2004. Kuva kansallisrunoilijastamme on juhlavuoden myötä muuttunut monisäikei- semmäksi. ”Ajattelin Runebergin ennen vanhukseksi, joka keksi Runebergin tortun.