Mapping the British Biopic: Evolution, Conventions, Reception and Masculinities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

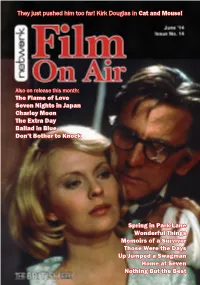

Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! the Flame of Love

They just pushed him too far! Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! Also on release this month: The Flame of Love Seven Nights in Japan Charley Moon The Extra Day Ballad in Blue Don’t Bother to Knock Spring in Park Lane Wonderful Things Memoirs of a Survivor Those Were the Days Up Jumped a Swagman Home at Seven Nothing But the Best Julie Christie stars in an award-winning adaptation of Doris Lessing’s famous dystopian novel. This complex, haunting science-fiction feature is presented in a Set in the exotic surroundings of Russia before the First brand-new transfer from the original film elements in World War, The Flame of Love tells the tragic story of the its as-exhibited theatrical aspect ratio. doomed love between a young Chinese dancing girl and the adjutant to a Russian Grand Duke. One of five British films Set in Britain at an unspecified point in the near- featuring Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, The future, Memoirs of a Survivor tells the story of ‘D’, a Flame of Love (also known as Hai-Tang) was the star’s first housewife trying to carry on after a cataclysmic war ‘talkie’, made during her stay in London in the early 1930s, that has left society in a state of collapse. Rubbish is when Hollywood’s proscription of love scenes between piled high in the streets among near-derelict buildings Asian and Caucasian actors deprived Wong of leading roles. covered with graffiti; the electricity supply is variable, and water is now collected from a van. -

New Arabian Nights

1882 NEW ARABIAN NIGHTS Robert Louis Stevenson Stevenson, Robert Louis (1850-1894) - Scottish novelist, poet, and essayist, best known for his adventure stories. Stevenson was a sickly man (he died of tuberculosis) who nevertheless led an adventurous life. He spent his last five years on the island of Samoa as a planter and chief of the natives. The New Arabian Nights (1882) - A collection of tales including “The Suicide Club,” “The Rajah’s Diamond,” “The Pavilion on the Links,” and more. This was Stevenson’s first published collection of fiction. TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW ARABIAN NIGHTS . 2 CONTENTS . 2 STORY OF THE YOUNG MAN WITH THE CREAM TARTS . 3 STORY OF THE PHYSICIAN AND THE SARATOGA TRUNK . 16 THE ADVENTURE OF THE HANSOM CABS . 27 THE RAJAH’S DIAMOND, STORY OF THE BANDBOX . 36 STORY OF THE YOUNG MAN IN HOLY ORDERS . 47 STORY OF THE HOUSE WITH THE GREEN BLINDS . 53 THE ADVENTURE OF PRINCE FLORIZEL AND A DETECTIVE . 66 THE PAVILION ON THE LINKS TELLS HOW I CAMPED IN GRADEN SEA-WOOD, AND BEHELD A LIGHTIN THE PAVILION . 69 TELLS OF THE NOCTURNAL LANDING FROM THE YACHT . 73 TELLS HOW I BECAME ACQUAINTED WITH MY WIFE . 75 TELLS IN WHAT A STARTLING MANNER I LEARNED THAT I WAS NOT ALONE IN GRADEN SEA-WOOD . 79 TELLS OF AN INTERVIEW BETWEEN NORTHMOUR, CLARA, AND MYSELF83 TELLS OF MY INTRODUCTION TO THE TALL MAN . 85 TELLS HOW A WORD WAS CRIED THROUGH THE PAVILION WINDOW 88 TELLS THE LAST OF THE TALL MAN . 91 TELLS HOW NORTHMOUR CARRIED OUT HIS THREAT . -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Taboo : why are real-life British serial killers rarely represented on film? EARNSHAW, Antony Robert Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20984/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Taboo: Why are Real-Life British Serial Killers Rarely Represented on Film? Antony Robert Earnshaw Sheffield Hallam University MA English by Research September 2017 1 Abstract This thesis assesses changing British attitudes to the dramatisation of crimes committed by domestic serial killers and highlights the dearth of films made in this country on this subject. It discusses the notion of taboos and, using empirical and historical research, illustrates how filmmakers’ attempts to initiate productions have been vetoed by social, cultural and political sensitivities. Comparisons are drawn between the prevalence of such product in the United States and its uncommonness in Britain, emphasising the issues around the importing of similar foreign material for exhibition on British cinema screens and the importance of geographic distance to notions of appropriateness. The influence of the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) is evaluated. This includes a focus on how a central BBFC policy – the so- called 30-year rule of refusing to classify dramatisations of ‘recent’ cases of factual crime – was scrapped and replaced with a case-by-case consideration that allowed for the accommodation of a specific film championing a message of tolerance. -

Backlash Over Blair's School Revolution

Section:GDN BE PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone:S Sent at 11/9/2005 19:33 cYanmaGentaYellowblack Chris Patten: How the Tories lost the plot This Section Page 32 Lady Macbeth, four-letter needle- work and learning from Cate Blanchett. Judi Dench in her prime Simon Schama: G2, page 22 Amy Jenkins: America will never The me generation be the same again is now in charge G2 Page 8 G2 Page 2 £0.60 Monday 12.09.05 Published in London and Manchester guardian.co.uk Bad’day mate Aussies lose their grip Column five Backlash over The shape of things Blair’s school to come revolution Alan Rusbridger elcome to the Berliner Guardian. No, City academy plans condemned we won’t go on calling it that by ex-education secretary Morris for long, and Wyes, it’s an inel- An acceleration of plans to reform state education authorities as “commissioners egant name. education, including the speeding up of of education and champions of stan- We tried many alternatives, related the creation of the independently funded dards”, rather than direct providers. either to size or to the European origins city academy schools, will be announced The academies replace failing schools, of the format. In the end, “the Berliner” today by Tony Blair. normally on new sites, in challenging stuck. But in a short time we hope we But the increasingly controversial inner-city areas. The number of acade- can revert to being simply the Guardian. nature of the policy was highlighted when mies will rise to between 40 and 50 by Many things about today’s paper are the former education secretary Estelle next September. -

Teaching Social Issues with Film

Teaching Social Issues with Film Teaching Social Issues with Film William Benedict Russell III University of Central Florida INFORMATION AGE PUBLISHING, INC. Charlotte, NC • www.infoagepub.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Russell, William B. Teaching social issues with film / William Benedict Russell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60752-116-7 (pbk.) -- ISBN 978-1-60752-117-4 (hardcover) 1. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Audio-visual aids. 2. Social sciences--Study and teaching (Secondary)--Research. 3. Motion pictures in education. I. Title. H62.2.R86 2009 361.0071’2--dc22 2009024393 Copyright © 2009 Information Age Publishing Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Contents Preface and Overview .......................................................................xiii Acknowledgments ............................................................................. xvii 1 Teaching with Film ................................................................................ 1 The Russell Model for Using Film ..................................................... 2 2 Legal Issues ............................................................................................ 7 3 Teaching Social Issues with Film -

DAVID WILLIAMSON Is Australia's Best Known and Most Widely

DAVID WILLIAMSON is Australia’s best known and most widely performed playwright. His first full-length play The Coming of Stork was presented at La Mama Theatre in 1970 and was followed by The Removalists and Don’s Party in 1971. His prodigious output since then includes The Department, The Club, Travelling North, The Perfectionist, Sons of Cain, Emerald City, Top Silk, Money and Friends, Brilliant Lies, Sanctuary, Dead White Males, After the Ball, Corporate Vibes, Face to Face, The Great Man, Up For Grabs, A Conversation, Charitable Intent, Soulmates, Birthrights, Amigos, Flatfoot, Operator, Influence, Lotte’s Gift, Scarlet O’Hara at the Crimson Parrot, Let the Sunshine and Rhinestone Rex and Miss Monica, Nothing Personal and Don Parties On, a sequel to Don’s Party, When Dad Married Fury, At Any Cost?, co-written with Mohamed Khadra, Dream Home, Happiness, Cruise Control and Jack of Hearts. His plays have been translated into many languages and performed internationally, including major productions in London, Los Angeles, New York and Washington. Dead White Males completed a successful UK production in 1999. Up For Grabs went on to a West End production starring Madonna in the lead role. In 2008 Scarlet O’Hara at the Crimson Parrot premiered at the Melbourne Theatre Company starring Caroline O’Connor and directed by Simon Phillips. As a screenwriter, David has brought to the screen his own plays including The Removalists, Don’s Party, The Club, Travelling North and Emerald City along with his original screenplays for feature films including Libido, Petersen, Gallipoli, Phar Lap, The Year of Living Dangerously and Balibo. -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

Click Here to Download The

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. 4 x 2” ad www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! June 25 - July 1, 2020 has a new home at INSIDE: THE LINKS! Sports listings, 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 sports quizzes Jacksonville Beach and more Pages 18-19 Offering: · Hydrafacials · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring · B12 Complex / Lipolean Injections ‘Hamilton’ – Disney+ streams Broadway hit Get Skinny with it! “Hamilton” begins streaming Friday on Disney+. (904) 999-0977 1 x 5” ad www.SkinnyJax.com Kathleen Floryan PONTE VEDRA IS A HOT MARKET! REALTOR® Broker Associate BUYER CLOSED THIS IN 5 DAYS! 315 Park Forest Dr. Ponte Vedra, Fl 32081 Price $720,000 Beds 4/Bath 3 Built 2020 Sq Ft. 3,291 904-687-5146 [email protected] Call me to help www.kathleenfloryan.com you buy or sell. 4 x 3” ad BY GEORGE DICKIE Disney+ brings a Broadway smash to What’s Available NOW On streaming with the T American television has a proud mistreated peasant who finds her tradition of bringing award- prince, though she admitted later to winning stage productions to the nerves playing opposite decorated small screen. -

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

The British Academy Television Awards Sponsored by Pioneer

The British Academy Television Awards sponsored by Pioneer NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED 11 APRIL 2007 ACTOR Programme Channel Jim Broadbent Longford Channel 4 Andy Serkis Longford Channel 4 Michael Sheen Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! BBC4 John Simm Life On Mars BBC1 ACTRESS Programme Channel Anne-Marie Duff The Virgin Queen BBC1 Samantha Morton Longford Channel 4 Ruth Wilson Jane Eyre BBC1 Victoria Wood Housewife 49 ITV1 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway ITV1 Stephen Fry QI BBC2 Paul Merton Have I Got News For You BBC1 Jonathan Ross Friday Night With Jonathan Ross BBC1 COMEDY PERFORMANCE Programme Channel Dawn French The Vicar of Dibley BBC1 Ricky Gervais Extra’s BBC2 Stephen Merchant Extra’s BBC2 Liz Smith The Royle Family: Queen of Sheba BBC1 SINGLE DRAMA Housewife 49 Victoria Wood, Piers Wenger, Gavin Millar, David Threlfall ITV1/ITV Productions/10.12.06 Kenneth Williams: Fantabulosa! Andy de Emmony, Ben Evans, Martyn Hesford BBC4/BBC Drama/13.03.06 Longford Peter Morgan, Tom Hooper, Helen Flint, Andy Harries C4/A Granada Production for C4 in assoc. with HBO/26.10.06 Road To Guantanamo Michael Winterbottom, Mat Whitecross C4/Revolution Films/09.03.06 DRAMA SERIES Life on Mars Production Team BBC1/Kudos Film & Television/09.01.06 Shameless Production Team C4/Company Pictures/01.01.06 Sugar Rush Production Team C4/Shine Productions/06.07.06 The Street Jimmy McGovern, Sita Williams, David Blair, Ken Horn BBC1/Granada Television Ltd/13.04.06 DRAMA SERIAL Low Winter Sun Greg Brenman, Adrian Shergold, -

Notice of a Regular Meeting

NOTICE OF A REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS OF THE OLIVENHAIN MUNICIPAL WATER DISTRICT 1966 Olivenhain Road, Encinitas, CA 92024 Tel: (760) 753-6466 • Fax: (760) 753-5640 VIA TELECONFERENCE ONLY Pursuant to AB3035, effective January 1, 2003, any person who requires a disability related modification or accommodation in order to participate in a public meeting shall make such a request in writing to Stephanie Kaufmann, Executive Secretary, for immediate consideration. DATE: WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2020 TIME: 4:00 P.M. PLACE: Remote Regular Meeting VIA TELECONFERENCE ONLY Pursuant to the State of California Executive Order N-35-20, and in the interest of public health, OMWD is temporarily taking actions to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic by holding Board Meetings electronically or by teleconference. The Boardroom will not be open to the public for this meeting. To join this meeting via phone, please dial: (669) 900-9128 or (346) 248-7799 Meeting ID: 914 8480 1481 and Password: 758077 Public Participation/Comment: Members of the public can participate in the meeting by emailing your speaker slip on an agenda item to the Board Secretary at [email protected] by 3:00 P.M. the day of the meeting. The subject line of your email should clearly state the item number you are commenting on and should include your name and phone number to ensure you are called on and have the opportunity to comment. All comments will be emailed to the Board of Directors. NOTE: ITEMS ON THE AGENDA MAY BE TAKEN OUT OF SEQUENTIAL ORDER AS THEIR PRIORITY IS DETERMINED BY THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1. -

The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter provides an introduction to one of the world’s leading and most controversial writers, whose output in many genres and roles continues to grow. Harold Pinter has written for the theatre, radio, television and screen, in addition to being a highly successful director and actor. This volume examines the wide range of Pinter’s work (including his recent play Celebration). The first section of essays places his writing within the critical and theatrical context of his time, and its reception worldwide. The Companion moves on to explore issues of performance, with essays by practi- tioners and writers. The third section addresses wider themes, including Pinter as celebrity, the playwright and his critics, and the political dimensions of his work. The volume offers photographs from key productions, a chronology and bibliography. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521651239 - The Cambridge Companion to Harold Pinter Edited by Peter Raby Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy The Cambridge Companion to the French edited by P. E. Easterling Novel: from 1800 to the Present The Cambridge Companion to Old English edited by Timothy Unwin Literature The Cambridge Companion to Modernism edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Michael Levenson Lapidge The Cambridge Companion to Australian The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Literature Romance edited by Elizabeth Webby edited by Roberta L. Kreuger The Cambridge Companion to American The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women Playwrights English Theatre edited by Brenda Murphy edited by Richard Beadle The Cambridge Companion to Modern British The Cambridge Companion to English Women Playwrights Renaissance Drama edited by Elaine Aston and Janelle Reinelt edited by A.