“We Can't Even Play Ourselves”: Mixed-Race Actresses in the Early

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

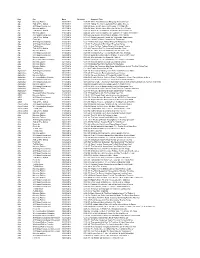

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

Paul Rudd Strikes a Comedic Pose While Bowling for Children Who Stutter

show ad Funnyman with a heart of gold! Paul Rudd strikes a comedic pose while bowling for children who stutter By Shyam Dodge PUBLISHED: 03:33 EST, 22 October 2013 | UPDATED: 03:34 EST, 22 October 2013 30 View comments He's known for being one of the funniest men working in Hollywood today. But Paul Rudd proved he's also got a heart of gold as he hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday. The 44-year-old actor could be seen throughout the fund raising event performing various comedic antics while bowling at the lanes. Gearing up: Paul Rudd hosted his second annual All-Star Bowling Benefit for children who stutter in New York, on Monday The I Love You, Man star taught some of the fundamentals of the sport to the children gathered for the event. But when it came his turn to demonstrate his bowling prowess it appeared he may have needed some practise in the art. Performing a comedic kick in the air after seeming to land the ball in the gutter the surrounding kids erupted into both applause and giggles. Getting a rise: The 44-year-old actor looked to have missed his mark during the event The set up: Rudd got his form down before letting loose But the antics also seemed to have been choreographed to entertain the youngsters, who the star was intent upon helping. Wearing brown suede loafers and tan chinos, Rudd went casual in a simple chequered button down shirt. -

Netflix's Dead to Me Ups Its Game for Season Two with Cooke Optics S7/I

PRESS RELEASE Netflix’s Dead to Me Ups Its Game for Season Two with Cooke Optics S7/i Full Frame Plus Prime Lenses - Cinematographer Toby Oliver, ACS, enhances photography with the ‘Cooke Look - Leicester, UK – 07 May 2020 – The Netflix original series Dead to Me has moved production to Cooke Optics S7/i Full Frame Plus prime lenses for season two to take advantage of the ‘Cooke Look®’ to bring a flattering look for stars Christina Applegate (nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Performance by an Actress in a Television Series - Musical or Comedy for season one) and Linda Cardellini. With season two set to air in 2020, the series chronicles the story of a powerful friendship that blossoms between a tightly wound widow and a free spirit with a shocking secret. When series creator and showrunner Liz Feldman wanted her main actresses to look their best on screen for season two, cinematographer Toby Oliver, ACS — who was brought on to lens the second season — decided that the “Cooke Look” would be exactly what was needed. “Liz wanted to maintain as much of the overall look of season one as possible, but she also wanted the main actresses to appear warmer on screen,” said Oliver. “To improve the photography from the first season, I decided that the Cooke S7/i Full Frame Plus prime lenses would give her exactly what she was looking for. I’ve used Cookes a lot over the years, and they are quite flattering, especially with close-ups. There’s just something about the ‘Cooke Look’ that makes actors look really good on screen – it gives the skin a nice glow.” This was to be Oliver’s first full frame project, shooting on Sony Venice cameras in 6K mode, using all of the full-frame sensor, so he did a range of lens tests at camera and lens supplier Alternative Rentals in Los Angeles. -

Screen Arts & Cultures

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF SCREEN ARTS & CULTURES FALL 2008 Viewing Screen Arts & Cultures Past, Present, and Future, a world-class education for screen scholars, screenwriters, and screen production in the mid-west. • SAC Honors projects (page 1) • New Doctoral Director (page 2) • Faculty Updates (page 10) • Future Challenges (inside back cover) Letter FROM THE CHAIR mentoring Sultan Shariff ’s EFEX project and Finally, an essay written by an English doctoral develop new diversity initiatives for the depart- student, Josh Lambert (for a SAC graduate ment. Chris McNamara and Terri Sarris won course on the emergence of mass culture and awards for their video productions, respec- early cinema), won second place in the 2007 tively, at the Ann Arbor Film Festival and the Society for Cinema and Media Studies Student Detroit Film Festival. Essay Award contest and then fi rst place in the Domitor Student Essay Award contest. Th e Department has welcomed Dan Herbert from the University of Southern Califor- Th e Department continues to initiate new nia as a new assistant professor specializing projects and augment others. Th e Hatcher Richard Abel in transnational fi lm adaptations and fi lm Library’s Special Collection acquired two industry practices. We also are in the midst of impressive collections: the Orson Welles My term as chair of Screen Arts & Cultures searches for four faculty positions, beginning Collection materials (photographs, fi lm will continue through June 2009. Challeng- in fall 2009: a senior position (open fi eld), -

Starlog Magazine Issue

23 YEARS EXPLORING SCIENCE FICTION ^ GOLDFINGER s Jjr . Golden Girl: Tests RicklBerfnanJponders Er_ her mettle MimilMif-lM ]puTtism!i?i ff?™ § m I rifbrm The Mail Service Hold Mail Authorization Please stop mail for: Name Date to Stop Mail Address A. B. Please resume normal Please stop mail until I return. [~J I | undelivered delivery, and deliver all held I will pick up all here. mail. mail, on the date written Date to Resume Delivery Customer Signature Official Use Only Date Received Lot Number Clerk Delivery Route Number Carrier If option A is selected please fill out below: Date to Resume Delivery of Mail Note to Carrier: All undelivered mail has been picked up. Official Signature Only COMPLIMENTS OF THE STAR OCEAN GAME DEVEL0PER5. YOU'RE GOING TO BE AWHILE. bad there's Too no "indefinite date" box to check an impact on the course of the game. on those post office forms. Since you have no Even your emotions determine the fate of your idea when you'll be returning. Everything you do in this journey. You may choose to be romantically linked with game will have an impact on the way the journey ends. another character, or you may choose to remain friends. If it ever does. But no matter what, it will affect your path. And more You start on a quest that begins at the edge of the seriously, if a friend dies in battle, you'll feel incredible universe. And ends -well, that's entirely up to you. Every rage that will cause you to fight with even more furious single person you _ combat moves. -

Wells College Association of Alumnae and Alumni

WellsNotes Spring 2020 Wells College Alumnae and Alumni Newsletter Wells College Association of Alumnae and Alumni WCA TO HONOR TWO DISTINGUISHED ALUMNAE THIS MAY The Wells College Association of Alumnae and Alumni (WCA) is proud to announce the two recipients of the 2020 WCA Award: Gwen Wilkinson ’77 and Stephanie Batcheller ’79. Both alumnae have had distinguished careers in the field of law with a particular emphasis on public service: Gwen as a district attorney and social justice advocate, and Stephanie as a public defender and legal educator. GWEN WILKINSON ’77 STEPHANIE BATCHELLER ’79 The Wells College Association of Alumnae The Wells College Association of Alumnae and Alumni is honoring Gwen Wilkinson and Alumni is honoring Stephanie ’77 with the WCA Award in recognition Batcheller ’79 with the WCA Award for of her public service, especially in the her accomplishments in the field of law and prosecution of perpetrators of child abuse contributions to the justice system. and domestic violence and in addressing Stephanie, a career public defender who has other social justice issues. argued before courts in Georgia, Maryland Gwen established herself as a proactive, and New York, is a senior staff attorney with ethical and passionate advocate for social the New York State Defenders Association justice throughout her career as a prosecutor (NYSDA). Since 1998, she has been with the and social services attorney in Tompkins association’s nonprofit Public Defense Backup County, N.Y. Those same attributes define her work with community Center, where she serves as senior staff attorney, developing client- organizations, providing context for how her education at Wells framed centered representation training strategies for new public defense the passion and drive she is known for. -

The Pleasures of Verisimilitude in Biographical Fiction Films

As if Alive before Us: The Pleasures of Verisimilitude in Biographical Fiction Films Anneli Lehtisalo (University of Tampere) Introduction The biopic, or biographical fiction film, is characterised by the real or historical per- son as a protagonist (Custen 5; Taylor 22; Bingham, Whose Lives 8). Despite the acknowledged potential for artistic freedom in fiction film, this generic feature— the reference to the real world—informs the genre. Film-makers, reviewers and film scholars repeatedly ask, how truthful or verisimilar a portrayal, an actor or a performance is or how well a biographical film depicts a historical story. Tradition- ally, film-makers have defined “the degree of truth” of a film at its opening (Custen 51). A title card or a voice-over might assert that the film follows known facts. The declaration can serve as a disclaimer, where the audience is informed that a film is only inspired by real events or the story is only partly factual. Thus, it is possible to specify a biopic as fictional. In any case, some definition is expected. Contempo- rary newspaper criticism commonly estimates the truthfulness and verisimilitude of a film. If a film portrays a famous or respected public figure, the authenticity of the depiction will almost inevitable be debated. In addition, the truthfulness and verisimilitude of biopics are constantly discussed in scholarly criticism. George F. Custen, in his seminal book Bio/Pics: How Hollywood Constructed Public His- tory, devotes a whole chapter to the discussion of the relationship between a real person and a protagonist in a film (110–47). His aim is to illustrate how certain cir- cumstances of the film industry shaped the biopics of the studio era. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

America's Closet Door: an Investigation of Television and Its Effects on Perceptions of Homosexuality

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 12-2014 America's closet door: an investigation of television and its effects on perceptions of homosexuality Sara Moroni University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Moroni, Sara, "America's closet door: an investigation of television and its effects on perceptions of homosexuality" (2014). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. America’s Closet Door An Investigation of Television and Its Effects on Perceptions of Homosexuality Sara Moroni Departmental Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga English Project Director: Rebecca Jones, PhD. 31 October 2014 Christopher Stuart, PhD. Heather Palmer, PhD. Joanie Sompayrac, J.D., M. Acc. Signatures: ______________________________________________ Project Director ______________________________________________ Department Examiner ____________________________________________ Department Examiner ____________________________________________ Liaison, Departmental Honors Committee ____________________________________________ Chair, Departmental Honors Committee 2 Preface The 2013 “American Time Use Survey” conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics calculated that, “watching TV was the leisure activity that occupied the most time…, accounting for more than half of leisure time” for Americans 15 years old and over. Of the 647 actors that are series regulars on the five television broadcast networks (ABC, CBS, The CW, Fox, and NBC) 2.9% were LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender) in the 2011-2012 season (GLAAD). -

Representations and Receptions of Genders and Sexualities in Showtime’S the L Word

GRAAT issue # 2 – June 2007 Queerer Than Thou: Representations and Receptions of Genders and Sexualities in Showtime’s The L Word Kimberly Campanello Florida Gulf Coast University I love the fact that Ilene does what she wants and doesn’t bother giving in to critics’ demands etc., whether the fan kind or otherwise. I think this is what has propelled the series to its successful status and has made it acceptable for it to deal with issues that most other series can’t or don’t get away with. Bittersweet on OurChart.com Do I think every character is representative of every lesbian that I know? Probably not, then most lesbians that I know work everyday, want a nice place to live, want a decent partner and just do about the same things that every heterosexual person does. This is a TV show. It's a soap opera, albeit a classy one. I, for one, will continue to watch, subscribe to Showtime, and post measured commentary on the site. Filmlover on OurChart.com I. Contexts I would like to provide some context for this paper on The L Word from recent news stories which directly relate to American culture’s continuing struggle with normative views of gender and sexuality. In February of 2007, Largo, Florida, city manager Steve Stanton, a 17-year veteran in his job was fired by a city council vote after coming out as a transgendered person. Sexual orientation and gender identity and expression are not protected from employment discrimination at the national level or in the state of Florida. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced.