Security Responses in Jonglei State in the Aftermath of Inter-Ethnic Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interaction Between International Aid and South Sudanese

Lost in Translation: The interaction between international humanitarian aid and South Sudanese accountability systems September 2020 This research was conducted by the Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility (CSRF) in August and September 2019 and was funded by the UK, Swiss, Dutch and Canadian donor missions in South Sudan. The CSRF is implemented by a consortium of the NGOs Saferworld and swisspeace. It is intended to support conflict-sensitive aid programming in South Sudan. This research would not have been possible without the South Sudanese and international aid actors who generously gave their time and insights. It is dedicated to the South Sudanese aid workers who tirelessly balance their personal and professional cultures to deliver assistance to those who need it. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Methodology and limitations ........................................................................................................................... -

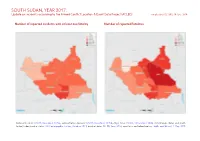

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SSNBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, October 2011; incident data: ACLED, June 2018; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 604 300 3351 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 404 299 1348 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2017 2 Strategic developments 120 0 0 Riots/protests 46 1 3 Methodology 3 Remote violence 25 3 17 Conflict incidents per province 4 Non-violent activities 1 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 1200 603 4719 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). Disclaimer 5 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2017 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). 2 SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Methodology an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province is known. -

RVI Local Peace Processes in Sudan.Pdf

Rift Valley Institute ﻤﻌﻬﺪ اﻷﺨدود اﻟﻌﻇﻴم Taasisi ya Bonde Kuu ySMU vlˆ yU¬T tí Machadka Dooxada Rift 东非大裂谷研究院 Institut de la Vallée du Rift Local Peace Processes in Sudan A BASELINE STUDY Mark Bradbury John Ryle Michael Medley Kwesi Sansculotte-Greenidge Commissioned by the UK Government Department for International Development “Our sons are deceiving us... … Our soldiers are confusing us” Chief Gaga Riak Machar at Wunlit Dinka-Nuer Reconciliation Conference 1999 “You, translators, take my words... It seems we are deviating from our agenda. What I expected was that the Chiefs of our land, Dinka and Nuer, would sit on one side and address our grievances against the soldiers. I differ from previous speakers… I believe this is not like a traditional war using spears. In my view, our discussion should not concentrate on the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer, but on the soldiers, who are the ones who are responsible for beginning this conflict. “When John Garang and Riek Machar [leaders of rival SPLA factions] began fighting did we understand the reasons for their fighting? When people went to Bilpam [in Ethiopia] to get arms, we thought they would fight against the Government. We were not expecting to fight against ourselves. I would like to ask Commanders Salva Mathok & Salva Kiir & Commander Parjak [Senior SPLA Commanders] if they have concluded the fight against each other. I would ask if they have ended their conflict. Only then would we begin discussions between the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer. “The soldiers are like snakes. When a snake comes to your house day after day, one day he will bite you. -

Heading with Word in Woodblock

Gambella Region Area Brief Regional Overview Gambella Peoples' region is one of the nine regional states of Ethiopia. This region is located at the western edge of the country bordering South Sudan. The capital of the region, Gambella, is 766km from Addis Ababa. This region has an estimated density of 10 people per square kilometre. The main ethnicities of the region are the Nuer (46.66%), the Anuak 21.16%), Amhara (8.42%), Kafficho (5.04%), Oromo (4.83%), Mezhenger (4%), Shakacho (2.27%), Kambata (1.44%), Tigrean (1.32%) and other ethnic groups predominantly from southern Ethiopia 4.86%. Children below the age of 18 years accounts for 66.5% (27,974) of the refugee population. Female (women and girls) significantly outnumber male (adult & young men) due to the fact that sizable number of adult and young men died during the 21 years of liberation struggle. Currently there are three refugee camps in Gambella region namely Pugnido, Leite Chore and Okugo which host about 68,000 refugees from South Sudan. Pugnido, 876 kilometres from Addis Ababa to the south west is the oldest refugee camp, which is hosting 42,044 refugees and has existed since 1992 while Okugo, which hosts 5,927 refugees, was established in mid 2013 following interethnic clash between Nuer and Murle people. Leite Chore refugee camp, which is under establishment, will host 20,000 South Sudanese asylum seekers displaced from their homeland due to the countrywide deadly armed conflict that erupted in December, 2013 between the supporters of President Salva Kir and the former vice president Dr. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

Clanship, Conflict and Refugees: an Introduction to Somalis in the Horn of Africa

CLANSHIP, CONFLICT AND REFUGEES: AN INTRODUCTION TO SOMALIS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA Guido Ambroso TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE CLAN SYSTEM p. 2 The People, Language and Religion p. 2 The Economic and Socials Systems p. 3 The Dir p. 5 The Darod p. 8 The Hawiye p. 10 Non-Pastoral Clans p. 11 PART II: A HISTORICAL SUMMARY FROM COLONIALISM TO DISINTEGRATION p. 14 The Colonial Scramble for the Horn of Africa and the Darwish Reaction (1880-1935) p. 14 The Boundaries Question p. 16 From the Italian East Africa Empire to Independence (1936-60) p. 18 Democracy and Dictatorship (1960-77) p. 20 The Ogaden War and the Decline of Siyad Barre’s Regime (1977-87) p. 22 Civil War and the Disintegration of Somalia (1988-91) p. 24 From Hope to Despair (1992-99) p. 27 Conflict and Progress in Somaliland (1991-99) p. 31 Eastern Ethiopia from Menelik’s Conquest to Ethnic Federalism (1887-1995) p. 35 The Impact of the Arta Conference and of September the 11th p. 37 PART III: REFUGEES AND RETURNEES IN EASTERN ETHIOPIA AND SOMALILAND p. 42 Refugee Influxes and Camps p. 41 Patterns of Repatriation (1991-99) p. 46 Patterns of Reintegration in the Waqoyi Galbeed and Awdal Regions of Somaliland p. 52 Bibliography p. 62 ANNEXES: CLAN GENEALOGICAL CHARTS Samaal (General/Overview) A. 1 Dir A. 2 Issa A. 2.1 Gadabursi A. 2.2 Isaq A. 2.3 Habar Awal / Isaq A.2.3.1 Garhajis / Isaq A. 2.3.2 Darod (General/ Simplified) A. 3 Ogaden and Marrahan Darod A. -

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War”

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War” Africa Report N°221 | 22 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jonglei’s Conflicts Before the Civil War ........................................................................... 3 A. Perpetual Armed Rebellion ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Politics of Inter-Communal Conflict .................................................................. 4 1. The communal is political .................................................................................... 4 2. Mixed messages: Government response to intercommunal violence ................. 7 3. Ethnically-targeted civilian disarmament ........................................................... 8 C. Region over Ethnicity? Shifting Alliances between the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, Greater Bor Dinka and Nuer ...................................................................................... 9 III. South Sudan’s Civil War in Jonglei .................................................................................. 12 A. Armed Factions in Jonglei ........................................................................................ -

Murle History

The History of Murle Migrations The Murle people live in southeastern Sudan and are proud to be Murle. They are proud of their language and customs. They also regard themselves as distinct from the people that live around them. At various times they have been at war with all of the surrounding tribes so they present a united front against what they regard as hostile neighbors. The people call themselves Murle and all other peoples are referred to as moden. The literal translation of this word is “enemy,” although it can also be translated as “strangers.” Even when the Murle are at peace with a given group of neighbors, they still refer to them as moden. The neighboring tribes also return the favor by referring to the Murle as the “enemy.” The Dinka people refer to the Murle as the Beir and the Anuak call them the Ajiba. These were the terms originally used in the early literature to refer to the Murle people. Only after direct contact by the British did their self-name become known and the term Murle is now generally accepted. The Murle are a relatively new ethnic group in Sudan, having immigrated into the region from Ethiopia. The language they speak is from the Surmic language family - languages spoken primarily in southwest Ethiopia. There are three other Surmic speaking people groups presently living in the Sudan: the Didinga, the Longarim and the Tenet. When I asked the Murle elders about their origins they always pointed to the east and said they originated in a place called Jen. -

State of Theworld's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2009

Education special minority rights group international State of theWorld’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2009 Events of 2008 State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2009 Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International Minority Rights Group International (MRG) 54 Commercial Street, London, E1 6LT, United gratefully acknowledges the support of all organizations Kingdom. Tel +44 (0)20 7422 4200, Fax +44 (0)20 and individuals who gave financial and other assistance 7422 4201, Email [email protected] to this publication, including UNICEF and the Website www.minorityrights.org European Commission. Getting involved Minority Rights Group International MRG relies on the generous support of institutions Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a and individuals to further our work. All donations non-governmental organization (NGO) working to received contribute directly to our projects with secure the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peoples. minorities and indigenous peoples worldwide, One valuable way to support us is to subscribe and to promote cooperation and understanding to our report series. Subscribers receive regular between communities. Our activities are focused MRG reports and our annual review. We also on international advocacy, training, publishing and have over 100 titles which can be purchased outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by from our publications catalogue. In addition, our worldwide partner network of organizations MRG publications are available to minority and which represent minority and indigenous peoples. indigenous peoples’ organizations through our MRG works with over 150 organizations in library scheme. nearly 50 countries. Our governing Council, which MRG’s unique publications provide well- meets twice a year, has members from 10 different researched, accurate and impartial information on State of countries. -

Pochalla County

Report on Food Security & Livelihoods Assessment in Pochalla County September 2014 Compiled by: Mawa Isaac J. Email: [email protected] [email protected] Web: www.spedp.org Table of Content Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………………..2 Abbreviations and acronyms……………………………………………………………………....3 Contacts: Partner NGOs on the Ground…………………………………………………………...4 Executive summary………………………………………………………………………………..5 Objectives of the assessment……………………………………………………………………...8 Approach and Methodology used during the assessment…………………………………………8 Limitations of the assessment……………………………………………………………………10 Needs analysis................................................................................................................................11 Emergency context – Pochalla County ………………………………………………………….12 Findings of the assessment.............................................................................................................14 Household food consumption patterns...........................................................................................14 Food security past and current trends……………………………………………………………15 Sources of Income.........................................................................................................................17 Fishing industry………………………………………………………………………………….17 Market outlook, access and perceptions…………………………………………………………18 Agriculture and Livelihoods potential – Pochalla County……………………………………….19 Seasonal Calendar – Pochalla County…………………………………………………………...20 Coping mechanism.........................................................................................................................21 -

Security Responses in Jonglei State in the Aftermath of Inter-Ethnic Violence

Security responses in Jonglei State in the aftermath of inter-ethnic violence By Richard B. Rands and Dr. Matthew LeRiche Saferworld February 2012 1 Contents List of acronyms 1. Introduction and key findings 2. The current situation: inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei 3. Security responses 4. Providing an effective response: the challenges facing the security forces in South Sudan 5. Support from UNMISS and other significant international actors 6. Conclusion List of Acronyms CID Criminal Intelligence Division CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement CRPB Conflict Reduction and Peace Building GHQ General Headquarters GoRSS Government of the Republic of South Sudan ICG International Crisis Group MSF Medecins Sans Frontières MI Military Intelligence NISS National Intelligence and Security Service NSS National Security Service SPLA Sudan People’s Liberation Army SPLM Sudan People’s Liberation Movement SRSG Special Representative of the Secretary General SSP South Sudanese Pounds SSPS South Sudan Police Service SSR Security Sector Reform UNMISS United Nations Mission in South Sudan UYMPDA Upper Nile Youth Mobilization for Peace and Development Agency Acknowledgements This paper was written by Richard B. Rands and Dr Matthew LeRiche. The authors would like to thank Jessica Hayes for her invaluable contribution as research assistant to this paper. The paper was reviewed and edited by Sara Skinner and Hesta Groenewald (Saferworld). Opinions expressed in the paper are those of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of Saferworld. Saferworld is grateful for the funding provided to its South Sudan programme by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) through its South Sudan Peace Fund and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) through its Global Peace and Security Fund. -

49A65b110.Pdf

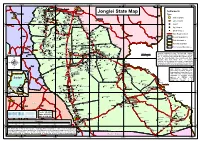

30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E Buheyrat No ") Popuoch Maya Sinyora Wath Wang Kech Malakal Dugang New Fangak Juaibor " Fatwuk " Pul Luthni Doleib Hill Fakur Ful Nyak " Settlements Rub-koni Ngwer Gar Keuern Fachop " Mudi Kwenek Konna Jonglei State Map Yoynyang Kau Keew Tidfolk " Fatach Fagh Atar Nyiyar Wunalong Wunakir Type Jwol Dajo ") Tiltil Torniok Atar 2 Machar Shol Ajok Fangak Kir Nyin Yar Kuo " Nur Yom Chotbora AbwongTarom ") State Capitals Bentiu Chuth Akol Fachod Thantok Kuleny Abon Abwong Jat Paguir Abuong Ayiot Ariath OLD FANGAK Fangak " ") Kot Fwor Lam Baar Shwai Larger Towns Fulfam Fajur Malualakon Tor Lil Riep ") Madhol ATAR N Rier Mulgak N " " " Mayen Pajok Foan Wuriyang Kan 0 0 ' " ' Kaljak Dier Wunlam Upper Nile Towns 0 Gon Toych Wargar 0 ° Akuem Toch Wunrok Kuey ° 9 Long Wundong Ayien Gwung Tur Dhiak Kuei 9 Fulkwoz Weibuini Dornor Tam Kolatong Wadpir Wunapith Nyinabot Big Villages Fankir Yarkwaich Chuai Twengdeng Mawyek Muk Tidbil Fawal Wunador Manyang Gadul Nyadin Wunarual Tel Luwangni Small Villages Rublik List Wunanomdamir Piath Nyongchar Yafgar Paguil Kunmir Toriak Akai Uleng Fanawak Pagil Fawagik Kor Nyerol Nyirol Main Road Network Nyakang Liet Tundi Wuncum Tok Rial Kurnyith Gweir Lung Nasser Koch Nyod Falagh Kandak Pulturuk Maiwut " Famyr Tar Turuk ") County Boundaries Jumbel Menime Kandag Dor " Dur NYIROL Ad Fakwan Haat Agaigai Rum Kwei Ket Thol Wor Man Lankien State Boundaries Dengdur Maya Tawil Raad Turu Garjok Mojogh Obel Pa Ing Wang Gai Rufniel Mogok Maadin Nyakoi Futh Dengain Mandeng Kull